AARON BERECHIAH BEN MOSES OF MODENA

(d. 1639), Italian kabbalistic writer and compiler. Aaron was a cousin on his mother’s side of Leone *Modena. For the benefit of the pious members of his native Modena, Aaron compiled his Maavar Yabbok ("The Crossing of the Jabbok" (cf. Gen. 32:22), Venice, 1626, and often reprinted) comprising the readings, laws, and customs relating to the sick, deathbed, burial, and mourning rites. David Savivi of Siena published an abridged version under the title Magen David (Venice, 1676), and Samuel David b. Jehiel *Ottolengo, another entitled Keriah Ne’emanah (ibid., 1715). Aaron also compiled Ashmoret ha-Boker ("The Morning Watch," Mantua, 1624; Venice, 1720), containing prayers and supplications for the use of the pious confraternity Me’irei Shall ar in Modena, as well as Me’il Zedakah and Bigdei Kodesh (both Pisa, 1785), containing prayers and passages for study.

AARON H AKIMAN

(14th century), poet; lived in Baghdad. His prolific works include the incomplete divan presently in the Firkovich collection (Catalog der hebraeischen und samaritanischen Handschriften, 2 (1875), no. 72) in St. Petersburg; this contains a kinah on the persecution of the Jews of Baghdad in 1344 which describes the destruction of the city’s synagogues and the desecration of Torah scrolls. Outstanding among the poems of the divan are those in honor of resh galuta Sar Shalom (b. Phinehas); also included are several brief maqamas. His poems demonstrate the author’s expert knowledge of classical Spanish poetry and the Bible, but they lack originality.

AARONIDES

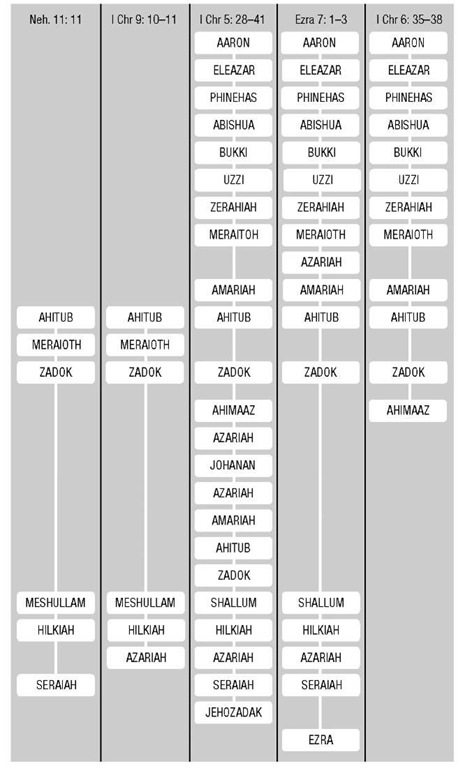

Members of the *priesthood in Israel. The traditional view is that throughout its history the legitimate priesthood comprised only those members of the tribe of *Levi descended directly from *Aaron, the first *high priest. The notion is anticipated in the Pentateuch by the use of such phrases as "for all time" and "throughout the ages" in connection with legislation of concern to "Aaron and his sons" (Ex. 27:21; 28:43; 30:8, 10, 19-21; Lev. 6:11, 15; 7:348".; 10:15 et al.). It is made explicit in the sharp distinction between the Aaronides and the other Levites who are made subordinate to them (Num. 3:10; 17:5; 18:1-7), and it is implicit in the designation of the priesthood in general by such terms as "the son(s) of Aaron" (Josh. 21:4, 10, 13, 19; Neh. 10:39; 12:47; 1 Chron. 6:39, 42; 12:27; 15:4; 23:28, 32; 24:1; cf. 1 Chron. 13:9; 26:28; 29:21; 31:19; 35:14), "the House of Aaron" (Ps. 115:10, 12; 118:3; 135:19), and, occasionally, simply "Aaron" (11 Chron. 12:27; 27:17; cf. Ps. 133:2). This same situation is assumed by the chronicler in the classification of the priestly clans according to the lines of Eleazar and Ithamar, sons of Aaron (1 Chron. 24:1-4). It is also reflected in the various genealogical lists of the high priests (Ezra 7:1-5; 1 Chron. 5:28-41; 6:35-38).

Genealogies of the Aaronides.

The Critical View

This picture of the history of the priesthood is regarded as an oversimplification of a very complex situation that can no longer be reconstructed with any degree of confidence. It is possible, however, to isolate the complexities. In the first place, the construction "sons of Aaron," in itself, like the terms "sons of Korah" and "sons of Asaph," may just as well refer to a professional class or guild as to blood kinship. That there were non-Aaronide priests, who were most likely incorporated into the Aaronide guild, may be inferred from the mention of priests prior to the Sinaitic revelation (Ex. 19:22, 24). Further, in the lifetime of Eleazar, son of Aaron, Joshua is said to have allotted 13 Canaanite cities with their pasture lands to the "sons of Aaron, the priests" (Josh. 21:19; cf. 21:4, 10, 13), an impossible situation unless the description "sons of Aaron" is not to be understood literally. Secondly, the exclusive priestly legitimacy of the Aaronides is characteristic of the p document, and is found elsewhere only in the book of Joshua and in the post-Exilic Nehemiah and Chronicles. It is not to be found in d, which seems to confer priestly status and privileges upon the entire tribe of Levi (Deut. 10:8-9, 18:6-7) and to postdate the selection of that tribe to the death of Aaron. Nor are the "sons of Aaron" mentioned in Judges, Samuel, Kings, or the prophets. Ezekiel never refers to them, only to the "levitical priests, the sons of Zadok" (Ezek. 40:46; 43:19; 44:15; cf. 48:11), without ever mentioning their Aaronic ancestry.

As to the clear differentiation between Aaronides and Levites, this may well argue against the historicity of the claim to an original levitical ancestry. One of the strands in the narrative of the revolt of Korah seems to reflect an Aaronide-Levite struggle for priestly prerogatives and to derive from a period before the levitical or Aaronic genealogizing of priests was effected (Num. 16; esp. 1 and 7-10). The same tension between the tribe of Levi and the Aaronides is apparent in the golden calf episode (Ex. 32:26-29). In this connection, it is regarded as significant that Aaron’s son Eleazar was buried at Gibeah, a town in the hill country of Ephraim belonging to his son, the high priest Phinehas (Josh. 24:33). It was precisely the bull-cult, with which the name of Aaron was associated, that was a characteristic of the religion of northern Israel (1 Kings 12:28-29). This suggests to some the possibility that the Aaronides were close to the Ephraimites and accounted for at least some of the priests of Beth-El (cf. ibid. 31; Judg. 20:26ff.). In this case, the description of Moses’ brother as "Aaron the Lev-ite" (Ex. 4:14) would be a later insertion into the text, it being in fact superfluous in its present context.

The post-Exilic genealogical lists of the Aaronide high priesthood present numerous problems. Missing entirely are the high priests Amariah (11 Chron. 19:11), Jehoiada (11 Kings 11:4; 12:10; 11 Chron. 23:1; 24:20), and Urijah (11 Kings 16:10-11, 15). The registers of 1 Chronicles (5:29-41 and 6:35-38) both list Ahimaaz, but not Azariah, while that of Ezra (7:1-6) records the latter, but omits the former. All three lists, however, have 12 generations between Aaron and the building of Solomon’s temple, which suggests schematization to accommodate the 480 years (or 12 40-year generations) supposed to have elapsed between the Exodus and the construction of the sanctuary (1 Kings 6:1). Further, 1 Chronicles (5:36-41) presupposes exactly another 12 generations between Solomon and the first high priest after the Restoration, but the repetition of Amariah, Ahitub, and Zadok (ibid. 33-34, 37-38) is suspicious. The genealogy of Ezra from Aaron lists only four high priests between Zadok of Solomon’s time and Ezra (Ezra 7:2). The fragmentary lists of 1 Chronicles (9:10-11) and Nehemiah (11:11) differ slightly from each other, and both vary from the other lists. Completely ignored in these genealogical tables is the line of Ithamar to which the Eli priesthood belonged. It is quite possible that the lists are interested only in the Zadokite high priests. At any rate, they cannot be used uncritically as source material for the history of the Aaronides.

Some scholars believe that the Aaronides constituted a priestly clan that had its origins in Egypt in pre-Mosaic times and very early embraced the new faith of Moses, anticipating in this respect the tribe of Levi. It used its prestige and influence among the people to gain support for Moses. This is regarded as being the real situation behind Exodus 4:14.0"., 27-31. Further corroboration of this theory is seen in the fact that in contrast to the justification for the selection of the clan of Phinehas (Num. 25:10-13) and the tribe of Levi (Ex. 32:26-29; Num. 3:12-13, 41, 45; 8:13-17), no reason is given for the choice of Aaron. The priesthood seems to come naturally to him. Another link in the chain of evidence is found in 1 Sam. 2:27-28, which tells of the selection of the house of Eli, undoubtedly considered Aaronide (1 Sam. 22:20; 1 Chron. 24:3), already in Egypt where it was the recipient of a divine revelation. No mention is made of any wilderness events or of the Levites. It is noted further that Egyptian names figure prominently in the Aaronide priesthood, viz., Hophni (1 Sam. 1:3), Phinehas (Ex. 6:25; 1 Sam. 1:3), Putiel (Ex. 6:25), Pashhur (Jer. 20:1; 21:1; Ezra 2:38), and Hanamel (Jer. 32:7). At some period, and in circumstances that can no longer be determined, the Aaronide priesthood amalgamated with the Levites and became the dominant priestly family. Its great antiquity and prestige ultimately generated the pattern of Aaronic genealogizing.

AARON OF BAGHDAD

(c. mid-ninth century), Babylonian scholar, described as the son of a certain R. Samuel, who lived in Jewish communities in southern Italy. In the sources he is referred to either as Aaron, or Abu Aaron, or Master Aaron (which might be a corrupted version of Abu Aaron). He met with several scholars in Oria, Lucca, and other communities, and many stories were told about his wisdom as well as his magical powers. His appearance is described in Megillat *Ahima’az, which is a literary chronicle of the *Kalonymus family in Italy, and in a document, written by Eliezer ben Judah of Worms in the second or third decade of the 13th century, tracing the history of the tradition of exegesis of prayers used by Eleazar and his teacher, *Judah b. Samuel he-Hasid. These two sources agree in attributing to Aaron, who is described by R. Eleazar as av kol ha-sodot ("father of all the secrets"), the transmission of certain doctrines and methods from the East to the West, to the Kalonymus family in Italy and Germany. As to the nature of these secrets, it is clear from Megillat Ahimaaz that before the arrival of Aaron, Jewish scholars in Italy were studying early mystical, eastern works, especially the mysticism of the Heikhalot and Merkabah. Eleazar’s words seem to prove that Aaron contributed to the Ashkenazi hasidic tradition of prayer exegesis. The stories in Megillat Ahimaaz suggest that he may have transmitted some magical formulae, as magic was one of the fields of study (usually secret) of both the Italian and the Ashkenazi scholars. There is no evidence that Aaron contributed anything to the development of theological doctrines or mystical speculations in these areas. Nor is there proof that any known book was written by Aaron or contained a contribution by him. However, in the traditions of the Kalonymus family, Aaron serves as the link connecting its own western culture with the revered centers of learning in Babylonia of the geonic period.

AARON OF LINCOLN

(c. 1123-1186), English financier. Aaron probably went to England from France as an adult. His recorded transactions extended over a great part of England and his clients included bishops, earls, barons, and the king of Scotland. Aaron advanced money to the crown on the security of future county revenues ("ferm of the shires"), as well as to various ecclesiastical foundations, such as the Monastery of St. Alban’s, for their ambitious building programs. Nine Cistercian abbeys owed him 6,400 marks for their acquisition of properties upon which he held mortgages. At one time Aaron worked in partnership with a rival Jewish financier, Le Brun of London. After Aaron’s death, his vast estate, which might have totaled as much as £100,000, was seized by the king. A special branch of the exchequer, the Scaccarium Aaronis, was established and administered the estate until 1191. Some of his debts were later resold to his son Elias. Aaron had no connection with the ancient house in Lincoln which now bears his name.

AARON OF NEUSTADT

(Blumlein; d. 1421), rabbinical scholar of Krems (Lower Austria). Aaron was a brother-in-law of Abraham *Klausner. He was a student, and then a colleague of Sar Shalom of Vienna (Wiener-Neustadt), and also of Jacob (Jekel) of Eger, rabbi in Vienna. Aaron was rabbi in Wiener-Neustadt and then in Vienna. A halakhic controversy arose between Aaron and Jacob on the question of non-Jews supplying Jewish prisoners with food on the Sabbath, a practice permitted by Aaron (Leket Yosher, ed. by J. Freimann, 1 (1903), 64). Aaron’s nephew and outstanding pupil was Israel b. Pethahiah *Isserlein, who often quotes his master’s biblical and talmudic teachings, in his Pesakim u-Khetavim (1519) and in his Beurim (1519). He refers, in particular, to Hilkhot Niddah, a halakhic compendium by Aaron. Among Aaron’s famous followers were Jacob b. Moses *Moellin (Maharil) and Isaac Tyrnau, author of Minhagim (1566), all of whom quote him. During the Vienna persecutions of 1420 Aaron was imprisoned and suffered severe tortures, from which he died.

AARON OF PESARO

(d. 1563), Italian lay scholar and bibliophile. A wealthy businessman of Novellara in northern Italy (not Nicolara, as in some works of reference), he later extended his interests to Gonzaga in the duchy of Mantua, where he was authorized to open a loan-bank in 1557. From a manuscript in his rich library the Mirkevet ha-Mishneh of Isaac Abrabanel was published in Sabionetta in 1551, the first Hebrew book printed there. His only known work is Toledot Aharon, a concordance of biblical passages cited in the Babylonian Talmud, arranged in the order of the Bible. After his death, his three sons, who succeeded him in his business, sent the manuscript of the work to the wandering Hebrew printer, Israel Zifroni, who published it at Freiburg in 1583-84, and Venice in 1591-92. Jacob *Sasportas appended to the work references from the Jerusalem Talmud (Toledot Yaakov, Amsterdam, 1652) while Aaron b. Samuel added references from other rabbinic and kabbalistic works (Beit Aharon, Frankfurt on the Oder, 1690-91). Toledot Aharon is printed in abbreviated form in most editions of the rabbinic Bible.

AARON OF YORK

(1190-1268), English financier, son of *Josce of York. Aaron was one of the wealthiest and most active English Jews living during the reign of Henry 111. In 1241 his estate was valued for taxation at £40,000, an incredible sum. He was *Presbyter Judaeorum of English Jewry in 1236-43. During these years, as he complained to the chronicler Matthew Paris, he was compelled to pay the king over 30,000 marks; he relinquished the office and died impoverished. He was styled nadiv ("benefactor") in Hebrew, an indication that he was probably a patron of scholarship.

AARON OF ZHITOMIR

(d. 1817), hasidic preacher in Zhitomir and other communities in Russia. His homilies on the weekly portions (parashiyyot) were recorded by his pupil Levi of Zhitomir and published in Toledot Aharon (Ber-dichev, 1817). In these, Aaron refrains from learned commentary and teaches "morality and pursuit of the service of God." Particular emphasis is given to devekut or adhesion to God.

AARON SAMUEL BEN MOSES SHALOM OF KRE-MENETS

(d. c. 1620), rabbi and author. A pupil of *Ephraim Solomon b. Aaron Luntschits when the latter was rabbi at Lemberg, Aaron Samuel was forced to immigrate to Germany as a youth. Toward the end of 1606 he was preaching in Fuerth. In 1611 he was in Eibelstadt (not, as often stated, Eisenstadt), Lower Franconia, where he wrote an ethical treatise entitled Nishmat Adam, on the origin and essence of the soul, the purpose of human life, and divine retribution (Hanau, 1611; Wilmersdorf, 1732). In 1615 he became rabbi in Fulda, where he wrote an introduction and notes to a homily on the Decalogue by Baruch Axelrod (Hanau, 1616). In his Nishmat Adam he mentions three unpublished works on ethical and religio-philosophical problems (Beer Sheva, Or Torah, and Ein Mishpat), as well as novellae to the Talmud, entitled Kitvei Kodesh.

AARON SAMUEL BEN NAPHTALI HERZ HA-KOHEN

(1740-1814), Polish rabbi. He served as rabbi to the communities of Stefan, Ostrog, Yampol, and Belaya Tserkov. He was an ardent follower of *Dov Baer of Mezhirech and Phinehas Shapira of Korets and was influenced by them in his views on Hasidism. He collected extracts from their statements in his books, Kodesh Hillulim (Lemberg, 1864). His talmudic novellae and his responsa were destroyed by fire. Only Kore me-Rosh, a commentary on the Midrash Rabbah, of which a portion only (part of Genesis) has been published (Berdichev, 1811), and Ve-Zivvah ha-Kohen, an ethical will to his children preceded by an anthology of homiletical and esoteric thoughts (Belaya Tserkov, 1823; Jerusalem, 1953), have survived.

AARON SELIG BEN MOSES OF ZOLKIEW

(d. 1643), kabbalist. His father, Moses Hillel, was president of the Jewish community in Brest-Litovsk; his brother Samuel was a parnas ("delegate") in the Council of the Four Lands. Aaron wrote a compendium of the Zohar entitled Ammudei Sheva ("Sevenfold Pillars," Cracow, 1635), in five volumes, with an introduction. The work comprises (1) a commentary, glosses, and explanations of difficult words in the Zohar, based on the works of Meir ibn *Gabbai, Moses *Cordovero, Judah *H ayyat, Me-nahem *Recanati, Elijah de *Vidas, Shabbetai Sheftel *Horow-itz, and on the notes to the Zohar by Menahem Tiktin in the margin of his copy; (2) sections from the Mantua edition of the Zohar of 1558-60 which are missing in the Cremona edition of 1558; (3) an index indicating where the various topics of the Zohar are commented upon by the six authors mentioned above; (4) a similar index for the Tikkunei Zohar; (5) a list of 39 parallel passages in the Zohar with their variant readings. The last volume is extremely rare.

AARON SIMEON BEN JACOB ABRAHAM OF COPENHAGEN

(late 18th century), secretary of the Jewish community of Cologne. Aaron is known for his participation in the important controversy known as the *Cleves get. Having personal knowledge of the entire case from its inception, Aaron sought to reverse the decision of Tevele Hess of Mannheim and of the Frankfurt rabbinate who had declared the divorce invalid. In conjunction with Israel b. Eliezer Lipschuetz, he appealed to all rabbis of authority in Germany, Holland, and Poland to permit the divorced woman, Leah Gunzhausen, to remarry. The majority expressed agreement with his point of view. He collected expert opinions and published them under the title Or ha-Yashar (Amsterdam, 1769; reprinted Lemberg, 1902, with notes by Jekuthiel Zalman Schor entitled Nizozei Or). Aaron also wrote Bekhi Neharot, a description of the flood at Bonn in 1784 (Amsterdam, 1784).

AARONSOHN

Family of pioneers in Erez Israel. efrayim fishel (1849-1939), one of the founders of Zikhron Ya’akov, was the father of the leaders of *Nili, aaron, alexander, and sarah. Born in Falticeni, Romania, he went to Erez Israel with his wife Malkah in 1882. He was a gifted farmer, which was an occupation he continued until the end of his long life.

Aaron

(1876-1919), agronomist, researcher, and founder of the Nili intelligence organization. Born in Romania, he was brought to Erez; Israel by his parents at the age of six and grew up in Zikhron Ya’akov. He was an unusual personality whose achievements and service to his people have not been fully appreciated.

His outstanding talents became evident from early childhood, and Baron Edmund de *Rothschild, the colony’s patron, generously sponsored his academic education at universities in France, Germany, and the United States.

The experimental station in *Athlit, near Haifa, which Aaronsohn founded on his return to Palestine, was a pioneering venture. It was there that his discovery of the ancestry of the wheat grain established his international reputation as an agricultural scientist.

Aaronsohn’s range of interests, however, far transcended his daily research. The social and political problems of his people always competed for his attention, but his greatest passion was for Palestine. His knowledge of the country and those adjacent to it, and of the habits of life of Jew and Arab, was unparalleled.

During World War i and afterwards, when he threw himself into the mainstream of Zionist political activity, this knowledge stood him in good stead, broadening his Weltanschauung. But Aaronsohn was not a popular leader. Though endowed with remarkable qualities, which put him head and shoulders above his contemporaries, his individualism operated against him. Temperamental and militant by nature, he was not an easy person to work with.

Aaronsohn’s conviction that the Zionist enterprise could flourish best under British protection had matured as early as 1912-13, when he was in New York. He refrained from publishing his views lest they embarrass the Berlin-based Zionist leadership. However, the brutal expulsion of Russian Jews from Jaffa in December 1914 finally shattered his hope that a modus vivendi with the Turk was possible.

During 1915-16 Palestine and its adjacent countries were infested with locusts. Djemal Pasha, the commander of the Ottoman Fourth Army, found that the only specialist competent to organize chemical warfare against the plague was Aaronsohn. The latter’s forthright manner and skill won the Pasha’s confidence but the closer their relationship became, the more concerned Aaronsohn grew about the future of his people.

With the tragedy that had befallen the Armenians at the back of his mind, he feared that at the slightest provocation Djemal would not hesitate to put an end to Zionist colonization. He therefore reached the radical conclusion that unless Palestine was speedily conquered by the British, the prospect for the survival of the Yishuv was slender.

It was for this reason that he made his way, by devious means, to England, leaving behind him a well-organized network of espionage. His second objective was to elicit some assurances of British sympathy for Zionist aspirations. On neither count was he successful at this stage, but unwittingly he converted his interlocutors at Military Intelligence to his cause.

Among those who fell under Aaronsohn’s spell should be mentioned: Major Walter Gribbon, the officer in charge of Turkish affairs at ghq; his close assistant, Captain Charles Webster; and Sir Mark Sykes.

Forty years later Sir Charles Webster testified how much his sympathy for the Jewish national ideal had deepened as a result of his admiration for Aaronsohn and his career:

It was he who gave me my first real contact with one of the Yishuv and I cannot forbear to mention how deep that impression was. It was made not only by the story of his great adventure during the war, but his unexampled knowledge of Palestine and his complete faith that this land could be made to blossom like the rose by Jewish skill and industry.

Such assurances were all the more important at that time because one of the arguments most frequently used was that it was quite impossible for Palestine to accommodate more than a fraction of the numbers which the Zionists claimed could be settled there.

Aaronsohn was equally successful in making converts among British officers both in political and military intelligence in Cairo, which he joined late in 1916. William Orsmsby-Gore, Wyndham Deedes, and Richard Meinerzhagen in particular, proved a source of strength to the Zionists.

Uppermost in Aaronsohn’s mind was a swift invasion of Palestine, to crush the Turk and deliver the Yishuv from disaster. It was he who alerted world public opinion to the evacuation of the Jewish population of Jaffa/Tel Aviv in April 1917; a policy which if followed to its conclusion could have resulted in a catastrophe. Exasperated by the sluggish British military advance, Aaronsohn was convinced that if properly handled, a blitz on the Palestinian front was possible.

British Intelligence was faulty and, in spite of all efforts, very little news could be elicited about enemy movements. Even when some information did filter through, it was too stale to be of any use. By contrast, not only did Aaronsohn gather a great deal of information, but by re-establishing contact with his group in Zikhron Ya’akov, he was able to furnish first-hand reports on Turkish troop movements, morale, and conditions behind enemy lines. Moreover, with his well-trained mind, he was able to give useful advice to the British on other matters, including military questions, so much so that it was humorously commented among the General Staff that "Aaronsohn is running the ghq." A co-author of the Palestine Handbook, an indispensable military guide, he was also invited to write for the prestigious Arab Bulletin.

It was not before the arrival of General *Allenby that full use was made of Aaronsohn’s suggestions. Allenby based his Beersheba operation on exhaustive intelligence data provided by the Aaronsohn group from behind the Turkish lines, which pointed to that sector as the weakest link in the enemy’s defenses and one where a British onslaught was least expected. Perhaps the most crucial information was that the wells in the region had been left untouched.

The British won a resounding victory but the Aaronsohn group was less fortunate. Their ring was uncovered by the Turkish authorities at the end of September. Eighteen months later Ormsby-Gore, paying tribute to the Aaronsohn family, wrote:

They were … the most valuable nucleus of our intelligence service in Palestine during the war. Aaronsohn’s sister was caught by the Turks and tortured to death, and the British Government owes a very deep debt of gratitude to the Aaronsohn family for all they did for us in the war … Nothing we can do for them … will repay the work they have done and what they have suffered for us.

General Macdonogh, the director of Military Intelligence, confirmed that Allenby’s victory would not have been possible without the information supplied by the Aaronsohn group.

In Brigadier Gribbon’s opinion it saved 30,000 British lives in the Palestine campaign. General Clayton considered the group’s service "invaluable," while Allenby singled out Aaronsohn as the staff officer chiefly responsible for the formation of Field Intelligence behind the Turkish lines. Sir Mark Sykes acknowledged that it was Aaronsohn’s idea of outflanking Gaza and capturing Beersheba by surprise that was the key to Allenby’s success.

The Foreign Office, too, had formed a high opinion of him, and his presence in London in autumn 1917, when the Balfour Declaration was still in the balance, assisted in creating a favorable climate of opinion for the Zionist cause.

Aaronsohn made a valuable contribution to the work of the Zionist Commission in Palestine in 1918, and his expertise was eagerly sought by the British and Zionist delegations to the Paris Peace Conference.

On May 15, 1919, Aaronsohn died tragically when a military aircraft taking him from London to Paris crashed in the Channel.

Alexander

(1888-1948), one of the founders of Nili. In 1913 he founded a short-lived semi-clandestine group for sons of farmers, called Gidonim, in his birthplace Zikhron Ya’akov. A precursor of Nili, the group had as one of its purposes the defense of the settlement. In 1915 he went to Egypt as an emissary of Nili to establish contact with the British Command. From there he went to the U.S., where he was active as an anti-Turkish and pro-Ally propagandist, and wrote With the Turks in Palestine (1917), a book on his personal experiences, exposing the evils of Turkish rule. After World War 1 he founded and for a time headed *Benei Binyamin, an organization of second-generation farmers in Palestine. He contributed to the Jerusalem newspaper Doar ha-Yom and published his memoirs, as well as booklets on Nili and its members. During World War 11 he served with the British Intelligence Service in its operations against Germany.

Sarah (1890-1917), martyr heroine of Nili. Born and educated in Zikhron Ya’akov, she married Hayyim Abraham, a Bulgarian Jew, in 1914, and moved to Constantinople. Her married life was unhappy and, in 1915, during World War 1, she returned to her family’s home. En route, she passed through Anatolia and Syria, and was an eyewitness to the savage persecution of the Armenians by the Turkish authorities. On her return to Zikhron Ya’akov, her brother Aaron enlisted her into Nili’s intelligence activities against Turkey. When he left the country, she supervised the agents’ operations and relayed information to the British in Egypt. Later, she was responsible for receipt of the gold sent through the Nili organization for help to the yishuv. In April 1917 she secretly visited Egypt to consult with her brother Aaron and the British Command. Warning her of the danger that threatened her in Erez Israel, they begged her to remain in Egypt, but she refused, and returned in June. In September, on learning that the espionage network had been uncovered by the Turkish authorities, she ordered its members to disperse, while she remained at home in Zikhron Ya’akov to avoid incriminating rumors, thus facilitating the escape of her fellow members. Arrested in her home on Oct. 1, 1917, she was subjected to brutal torture for four days, but disclosed nothing, and finally put an end to her suffering by shooting herself. In reverence to her memory, pilgrimages are made to her grave in Zikhron Ya’akov on the anniversary of her death. r , , ,

AARONSOHN, MICHAEL

(1896-1976), U.S. rabbi. Born in Baltimore, Aaronsohn attended the University of Cincinnati (B.A., 1923) and was ordained the same year at Hebrew Union College. When the U.S. entered World War I in April 1917, Aaronsohn, who was entitled to a clerical exemption from military service, enlisted the following month. When his parent expressed anxiety over his decision he wrote them that "as good Jews, you should [trust] in God implicitly … without a word of doubt or discouragement." An-tisemitism in the U.S. was on the rise during the war and one of the most common accusations was that Jews shirked military service. Aaronsohn, who rose to the rank of battalion sergeant-major (he served with the 147th Infantry Regiment, 39th Division of the aef), expressed disgust at Jewish draftees who claimed that they were ineligible for overseas duty because they were foreign born, telling his parents that "while I am a Jew and love everything that Judaism stands for, nevertheless I cannot stand for a hypocrite or a low down coward."

While attempting to pull a wounded comrade to safety during the Meuse-Argonne offensive (September 29, 1918), Aaronsohn was blinded by an artillery shell. After eight months at the Red Cross school for the blind he returned to Hebrew Union College and was able to complete his studies when the college hired his sister Dora to be his note taker. During his rabbinic career Aaronsohn promoted a number of causes associated with the mental and physically disabled, for example serving a term as president of the Hamilton County (Ohio) Council for Retarded Children. He was instrumental in founding the Jewish Braille Institute in 1931, which made Jewish texts such as the Bible and Talmud more widely accessible through a free monthly magazine called the Jewish Braille Review.

Aaronsohn also served as a chaplain to several organizations, such as the Disabled American Veterans and the Veterans of Foreign Wars. An active member of the Republican Party, he gave the invocation at the Republican National Convention in 1940 and unsuccessfully ran for Cincinnati City Council in 1949, where he campaigned for "a scientific system of taxation." Aaronsohn was the author of numerous articles and three books, including Broken Lights (1946), an autobiographical novel.

AARONSOHN, MOSES

(1805-1875), preacher, rabbi, and scholar. Born in Salant, Lithuania, Aaronsohn was a preacher (maggid) in Eastern Europe (Vishtinetz, Brotski, and Mir) and was recognized for his scholarship by 1836, when he published Pardes ha-Hokhmah, a book of sermons. He later published Pardes ha-Binah, a book of sermons with responsa. Aaronsohn arrived in the United States c. 1860, living on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, where he held services in his home and was known as "The East Broadway Maggid." For four years, he served as a preacher in a number of established synagogues, including Chevrat Vizhaner and the Allen Street Beth Hamedrash, which had split from the Beis Medrash Hagadol. In 1864, he became the rabbi at Congregation Adath Yeshurun in New York City. He continued to write responsa and also included the opinions of those rabbis in Eastern Europe with whom he corresponded regarding contemporary halakhic issues.

Aaronsohn was a strong personality with definite opinions, which eventually erupted into major controversies. He attacked the scholarship and practices of two New York rabbis who were eminent talmudic scholars, Rabbi Abraham Joseph *Ash and Rabbi Judah Mittleman, calling into question divorces written by Rabbi Ash and the kashrut of the animals slaughtered under the supervision of Rabbi Mittle-man – whom he accused of allowing improper bloodletting before shehitah. By 1873, when he criticized the kashrut of certain California wines, the hostility he created in the clergy caused him to be excommunicated by Ash and Mittleman, and he was forced to leave New York. For a time, he served as an itinerant preacher and finally settled in Chicago, where he died. His book on American responsa, Mattaei Mosheh, was published posthumously in 1878 in Jerusalem.

AARONSON, LAZARUS LEONARD

(1894-1966), English poet. A lecturer in economics at London University, Aaron-son published several verse collections, including Poems (1933) and The Homeward Journey (1946). Aaronson dealt at length with his conversion in Christ in the Synagogue (1930) but remained preoccupied with his spiritual duality as a Jew and an Englishman in a late poem, "The Jew" (1956).

ABADAN

Island and seaport located in the province of Khuzistan at the southwest corner of Iran on the left bank of Shatt al-Arab and about 60 km from the Persian Gulf. It grew into a big city because of its oil refinery. During World War 11 there were about 25,000 refinery employees out of a total population of 100,000. This was a period in which Abadan attracted a relatively large number of Jews from several cities in Iran, mainly from *Isfahan, *Bushire, *Shiraz, and *Ker-manshah. According to one source (Alam-e Yahud), at this time there were 200 Jewish families (about 800 people) living in Abadan, some of whom were Iraqi Jews. In addition, it has been reported that 300 out of 1,700 foreign professional refinery employees were Palestinian Jews belonging to *Solel Boneh. For this reason, one may say that the post-Reza Shah (1925-41) *He-H alutz movement and Zionist activities in Iran had, to some degree, their roots in the Jewish community of Abadan. Abadan played an important role in rescue missions of the Iraqi Jews during and after the independence of Israel. After the 1979 Islamic revolution, Jews began to leave the city. At the beginning of the 21st century there were few Jewish families living in Abadan, numbering fewer than 20 people.

ABARBANELL, LINA

(1879-1963), star of European light opera and Broadway doyenne. Born in Berlin to a prominent Sephardi family active in the professional theater, Abarbanell debuted as Adele in the Berlin Court Opera’s production of Die Fledermaus in 1904, at the age of 15. As a young woman, she toured European concert halls and theaters, establishing a career as a vocalist and actress. She won especial renown in the world of Viennese operetta, where luminaries of the scene, such as Franz Lehar and Oscar Straus, composed works for her. She spent a season in New York with the Metropolitan Grand Opera in 1905, appearing as Hansel in the American premiere of Humperdinck’s Hansel und Gretel. Abarbanell and her husband, Edward Goldbeck, an editorialist and cultural commentator, and their young daughter settled in Chicago soon after, returning to New York after World War 1.

In America, Abarbanell introduced the Viennese light musical repertoire to popular audiences and won fame and critical plaudits with starring roles in Lehar’s The Merry Widow, among other works. A fashionable, graceful, and vivacious personality, she helped popularize songs and dances of the musicals and light operas in which she appeared. With her husband, she hosted a weekly salon in her Chicago home for European and American artists and writers. Abarbanell essentially supported the family through her theater career, seeing them through bankruptcy in 1921. After the death of her husband in 1934, she transformed herself from performer to producer and director. Her daughter Eva Goldbeck, a fiction writer and reviewer who published in periodicals such as the New Republic, died in 1935 at the age of 34. Abarbanell maintained a close relationship with her son-in-law, the composer Marc Blitzstein (The Cradle Will Rock), for the rest of her life. She established a successful second career as casting director for Blitzstein and others, in theater (Porgy and Bess) and in film (Carmen Jones), and remained actively involved in the theater world until her death from heart failure shortly after her 84^ birthday.

ABBA

(Heb, ![]() Aramaic equivalent of the Hebrew (av, 2N; ABADDON (Heb.

Aramaic equivalent of the Hebrew (av, 2N; ABADDON (Heb. ![]() "place of destruction"). It is mentioned in the Wisdom literature of the Bible (Job 26:6; 28:22; 31:12; Prov. 15:11; Ps. 88:12); and it occurs also in the New Testament (Rev. 11:11) where, however, it is personified as the angel of the bottomless pit, whose name in Greek is "Apollyon" (AnoMuwv, "destroyer"). In the Talmud (Er. 19a) it is given as the second of the seven names of Gehenna (*Gehinnom), the proof verse being Psalms 88:12, while Midrash Konen makes it the actual second department of Gehenna.

"place of destruction"). It is mentioned in the Wisdom literature of the Bible (Job 26:6; 28:22; 31:12; Prov. 15:11; Ps. 88:12); and it occurs also in the New Testament (Rev. 11:11) where, however, it is personified as the angel of the bottomless pit, whose name in Greek is "Apollyon" (AnoMuwv, "destroyer"). In the Talmud (Er. 19a) it is given as the second of the seven names of Gehenna (*Gehinnom), the proof verse being Psalms 88:12, while Midrash Konen makes it the actual second department of Gehenna.

"Father"). The term was in common use from the first century onward (cf. Mark 14:36). In the early centuries of the Christian era it was used in both Jewish and Christian sources in addressing God, and in talmudic times as a prefix to Hebrew names, probably to designate an esteemed scholar (cf. Abba Hilkiah, Abba Saul). K. *Kohler, however, was of the opinion that the title referred specifically to Essenes. Because of its honorable association, it was forbidden to call slaves by this name (Ber. 16b). It often occurs independently, sometimes perhaps as an abbreviation of Abraham. Its fusion with the prefix "rav" (for "rabbi") gave rise in Babylonia to the names "Rabbah," "Rava," and to their abbreviated forms, "Ba" and "Va" in Palestine. It is a common name among Ashkenazi Jews in Eastern Europe and Israel, often used as an agnomen of Abraham. The word survives in European languages as an ecclesiastical designation (Abbas, Abt, Abbot), while in modern Hebrew it has largely displaced the Hebrew av as the popular term for "father."

ABBA

(Ba), two amoraim are known by this name.

(1) abba (late third and early fourth centuries), in his youth probably knew Rav and Samuel, the founders of rabbinic learning in Babylonia. He was, however, primarily a disciple of R. Huna and R. Judah, and frequently is mentioned together with their other disciples. Like R. Zeira, Abba ignored R. Judah’s prohibition to leave Babylonia and emigrated to Erez Israel (Ber. 24b). In Erez Israel Abba was a close friend of R. Zeira and other Palestinian scholars. In Tiberias he studied with R. Johanan’s chief disciples, R. Eleazar and Resh Lakish. After the death of Eleazar, leadership passed to R. Ammi and R. Assi, but Abba was considered equally great and was referred to in the Babylonian academies as "our teacher in the land of Israel" (Sanh. 17b). Abba dealt in silk (bk 117b) and became very wealthy. This enabled him to honor the Sabbath by buying 13 choice cuts from 13 butchers (Shab. 119a). A very charitable man, he never embarrassed the poor and would put money in his scarf which he would hang behind his back, so that the poor might take the money without him seeing their faces (Ket. 67b). He frequently revisited Babylonia, but always returned to Erez Israel for the festivals. Thus he transmitted Babylonian teaching and traditions to Erez Israel and vice versa (tj, Shev. 10:2,39c; Ned. 8:1,4od; bm 107a). When the body of his teacher Huna was brought from Babylonia for burial, Abba eulogized him, saying "Our teacher deserved to have the Shekhinah rest upon him, were it not that he lived in Babylonia" (mk 25a). Influential in both halakhah and aggadah, Abba’s teachings are found in the Babylonian and Palestinian Talmuds, as well as in the Midrash. (For a critical analysis of the traditions relating to the death and burial of Rav Huna, see S. Friedman, Historical Aggadah, pp. 146 ff.)

(2) abba (the later; fourth-fifth centuries), Palestinian amora. Abba went to Babylonia, probably during the anti-Jewish reaction following the death of *Julian the Apostate in 363 c.e. Abba is mentioned together with R. Ashi, to whom he transmitted the Palestinian tradition (bk 27b). He is also quoted as saying to R. Ashi: "You have derived teaching from this source, we derive it from a different one, as it is written: A land whose stones are iron’ [Deut. 8:9], Do not read ‘whose stones’ [n'JSX, avaneha] but rather ‘whose builders’ [H'Tia, boneha, i.e., sages]", meaning that a scholar who is not as hard as iron is no scholar (Ta’an. 4a; cf. Bek. 55a). He is not mentioned in the Palestinian Talmud.

ABBA

(Rava, Rabbah; eighth century), rabbinical scholar; disciple of *Yehudai Gaon and possibly also of *Ah a of Shabh a, the author of She’iltot. Abba is the author of Halakhot Pesukot, a juridical tract in the vein of She’iltot from which it apparently quotes. It was published in segments twice – first by S. Schechter and then by J.N. Epstein. A small monograph on the laws of phylacteries (probably part of a larger work), which has been attributed to Abba, was appended by *Asher b. Je-hiel – who calls it the work of a gaon – to his own laws on the subject, under the title Shimmusha Rabbah ("Rabbah’s Legal Practice"); it was printed in the Vilna edition of the Talmud in Asher’s Halakhot Ketannot at the end of tractate Menahot. *Judah b. Barzillai pointed out that many of its utterances run counter to talmudic regulations, a phenomenon which he attributed to errors by pupils and copyists. Among Abba’s best-known pupils was *Pirkoi b. Baboi.

ABBA BAR ALIA

(third century), amora. He was born in Erez Israel and emigrated to Babylonia (tj, Ber. 1:9,3d). Several halakhot are quoted by him in the Jerusalem Talmud in the name of "Rabbi" (Judah ha-Nasi) and in the Babylonian in that of "Rabbenu"; therefore he may have been a pupil of Judah ha-Nasi. In the Jerusalem Talmud (loc. cit.) Abba b. Ah a is quoted as saying in the name of Rabbi (according to Ber. 49a, cf. Dik. Sof. 258, in the name of Rabbenu): "If one fails to mention ‘covenant’ [i.e., the phrase 'for Thy covenant which Thou has sealed in our flesh'] in the Blessing for the Land or ‘the kingdom of the House of David’ in the blessing ‘who re-buildest Jerusalem’ [both in the Grace after Meals], it must be repeated correctly." R. Ilai reports decisions in his name (Ber. 49a, et al.). He is the author of the statement, "The nature of this people [Israel] is incomprehensible. Approached on behalf of the golden calf, they contribute; approached on behalf of the tabernacle, they contribute toward it too" (tj, Shek. 1.145d).

ABBA BAR AVINA

(third century), Palestinian amora. He was also called Abba b. Binah, Abba b. Minah, or simply Buna. He was of Babylonian origin and studied there at the academy of *Rav (cf. tj, Sanh. 3:3,2k) but later immigrated to Erez Israel. Among his pupils were R. *Abba b. Zavda and R. Berechiah. Most of his sayings are quoted in the Jerusalem Talmud and in the Midrash (e.g., Lev. R. 20:12); he is mentioned only once in the Babylonian Talmud (Shab. 60b). Abba b. Avina was consulted in legal questions (tj, ibid.) and seems to have officiated as a judge (tj, bm, 5:2,10a). He interpreted I Chronicles 22:14: "Behold in my straits I have prepared for the house of the Lord … etc." to teach that wealth does not matter before the Creator of the universe. A moving confession, composed by him, is quoted at the end of Jerusalem Talmud (Yoma 8:10,45c): "My God, I have sinned and done wicked things. I have persisted in my bad disposition and followed its direction. What I have done I will do no more. May it be Thy will, O Everlasting God, that Thou mayest blot out my iniquities, forgive all my transgressions, and pardon all my sins." The Palestinian amora, R. Higrah, was his brother (tj, Meg. 1:11,71c).

ABBA BAR KAHANA

(late third century), Palestinian amora. It is possible that he was the son of Kahana the Babylonian, the pupil of Rav who immigrated to Erez Israel. Abba quotes halakhot in the name of H anina b. H ama and Hiyya b. Ashi (Shab. 121b; tj, Ber. 6:6, 1od), but his talents lay largely in the realm of aggadah and, with his contemporary R. Levi, he was regarded as one of its greatest exponents (tj, Ma’as. 3:10,5 la). Early aggadic traditions of leading tannaim such as *Eliezer b. Hyrcanus, *Simeon b. Yoh ai, *Judah b. Ilai, and *Phinehas b. Jair were known to Abba. Among his statements are "Such is the way of the righteous: they say little and do much" (Deut. R. 1:11) and "No serpent ever bites below unless it is incited from above . nor does a government persecute a man unless it is incited from above" (Eccles. R. 10:11). This statement probably reflects the persecutions of the Jews of his time, to which there may also be a reference in the observation "The removal of the ring by Ahasuerus [Esth. 3:10] was more effective than the 48 prophets and seven prophetesses who prophesied to Israel but were unable to lead Israel back to better ways" (Meg. 14a). His homiletical interpretations deal with biblical exegesis; he identifies anonymous biblical personalities (e.g., Dinah was the wife of Job: Gen. R. 19:12, etc.) as well as geographical sites whose location was not clear (Kid. 72a). He embellishes the biblical narrative with tales and aggadot (Gen. R. 78:16; Eccles. R. 2:5, etc.). His statements reflect the contemporary hardships and persecutions suffered by the Jews (Lev. R. 15:9). Abba expresses his expectation of redemption in the remark that "if you see the student benches in Erez Israel filled with sectarians [Babylonians], look forward to the approaching steps of the Messiah" (Lam. R. 1:41); ibid., ed. Buber, 39a, however reads "every day" (Heb. DT ^32) instead of "Babylonians" (Heb. D"V22).

ABBA BAR MARTA

(third and first half fourth centuries), Babylonian amora. Some suggest that he was named after his mother because she cured him as a child after he’d been bitten by a mad dog (Yoma 84a). He owed a debt to the exilarch and was seized by his men on a Sabbath. However, the exilarch set him free because he was a scholar (Shab. 121b). In another incident Abba b. Marta managed to outwit the exilarch’s men who sought to hold him prisoner because of his debt (Yev. 120a). In another instance Abba b. Marta owed money to Rabbah, the head of the Pumbedita academy. He went to Rabbah with the intention of repaying his debt during the sabbatical year. Rabbah answered in accordance with the halakhah. "I cancel it." Abba b. Marta took the money back, instead of saying, as the procedure demanded, "Nevertheless, I insist.." Only after the intervention of Abbaye did he realize that he had not acted properly and repaid the debt (Git. 37b). Another contemporary scholar, Abba b. Menyamin (Menyomi, Benjamin) b. Hiyya, who expounded Mishnayot and asked a halakhic question of Huna b. Hiyya (Sot. 38b, Hul. 80a), is sometimes identified with Abba b. Marta.

ABBA BAR MEMEL

(third and the beginning of the fourth centuries), Palestinian amora. Some scholars consider that Memel refers to his place of residence, Mamla or Malah in Lower Galilee. He posed questions to R. Oshaya in Cae-sarea who may have been his teacher (tj, bk 2:1, 2d). Eleazar b. Pedat, one of his eminent contemporaries, refers to Abba Memel as his master (Ket. 111a). He discussed halakhic problems with R. Ammi, R. Assi, R. Zeira, and others, and halakhot are quoted in his name by many Palestinian sages. He is the author of several principles concerning the interpretation of the biblical text. A gezerah shavah ("inference from a similarity of phrases in texts") may be established to confirm but not to invalidate a teaching. One may deduce a kal va-homer (inference from minor to major) of one’s accord, but not a gezerah shavah. An argument may be refuted on the basis of a kal va-h omer, but not on the basis of a gezerah shavah (tj, Pes. 6:1, 33a). He also stated, "If I had someone who would agree with my view, I would permit … work to be done on the intermediate days of the festival. The reason why work is then prohibited is to enable people to eat and drink and study the Torah; but instead they eat and drink and engage in frivolity …" (tj, mk 2:3, 81b).

ABBA BAR ZAVDA

(third century), Palestinian amora. Abba studied in Babylonia, first under Rav and later under R. Huna. He returned to Erez Israel, where he became one of the leading scholars at the yeshivah of Tiberias. He quotes halakhot in the name of the last of the tannaim: R. Simeon b. H alafta, R. Judah ha-Nasi, and R. H iyya as well as R. H anina, R. Johanan, and Resh Lakish. After the deaths of R. Johanan and R. Eleazar b. Pedat, Abba b. Zavda became one of the most prominent sages in Erez Israel. At the yeshivah of Tiberias he was given the honor of opening the lecture which Ammi and Assi closed (tj, Sanh. 1:4, 18c). His humility is stressed by the sages (ibid., 3:5, 21a). His saying, "A Jew, even though he sins, remains a Jew" (Sanh. 44a) is well known. In a sermon delivered on a public fast day, Abba b. Zavda called on those who wished to repent first to mend their evil ways, for "if a man holds an unclean reptile in his hand, he can never become clean, even though he bathes in the waters of Shiloah or in the waters of creation" (tj, Ta’an. 2:1; in tb, Ta’an. 16a, the statement with slight variations is ascribed to Abba b. Ahavah).

ABBA BAR ZEMINA

(also Zimna, Zimona, Zevina; fourth century), Palestinian amora. His father was probably the Zem-ina who acted as "elder" of the Jews of Tyre (tj, Bik. 3:3, 65d). Abba’s principal teacher was Zeira. While working as a tailor in Rome, his employer offered him meat which had not been ritually slaughtered and threatened to kill him if he refused to eat it. When Abba chose death, his employer informed him that had he eaten, he would have killed him, saying, "if you are a Jew, be a Jew, if a Roman be a Roman" (tj, Shev. 4:2, 35a-b). The statement, "if our predecessors were as angels, we are as men; if they were men, we are as donkeys," is quoted by Abba b. Zemina in the name of Zeira (tj, Dem. 1:3, 21d; in Shabbat 112a, by Zeira in the name of Rabbah b. Zemina).