The invention: The most widely used procedure of its type, coronary bypass surgery uses veins from legs to improve circulation to the heart.

The people behind the invention:

Rene Favaloro (1923-2000), a heart surgeon

Donald B. Effler (1915- ), a member of the surgical team

that performed the first coronary artery bypass operation F. Mason Sones (1918- ), a physician who developed an

improved technique of X-raying the heart’s arteries

Fighting Heart Disease

In the mid-1960′s, the leading cause of death in the United States was coronary artery disease, claiming nearly 250 deaths per 100,000 people. Because this number was so alarming, much research was being conducted on the heart. Most of the public’s attention was focused on heart transplants performed separately by the famous surgeons Christiaan Barnard and Michael DeBakey. Yet other, less dramatic procedures were being developed and studied.

A major problem with coronary artery disease, besides the threat of death, is chest pain, or angina. Individuals whose arteries are clogged with fat and cholesterol are frequently unable to deliver enough oxygen to their heart muscles. This may result in angina, which causes enough pain to limit their physical activities. Some of the heart research in the mid-1960′s was an attempt to find a surgical procedure that would eliminate angina in heart patients. The various surgical procedures had varying success rates.

In the late 1950′s and early 1960′s, a team of physicians in Cleveland was studying surgical procedures that would eliminate angina. The team was composed of Rene Favaloro, Donald B. Effler, F. Mason Sones, and Laurence Groves. They were working on the concept, proposed by Dr. Arthur M. Vineberg from McGill University in Montreal, of implanting a healthy artery from the chest into the heart. This bypass procedure would provide the heart with another

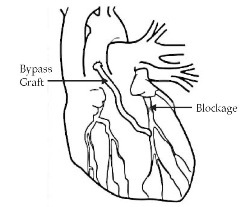

Before bypass surgery (left) the blockage in the artery threatens to cut off blood flow; after surgery to graft a piece of vein (right), the blood can flow around the blockage.

source of blood, resulting in enough oxygen to overcome the angina. Yet Vine-berg’s surgery was often ineffective because it was hard to determine exactly where to implant the new artery.

New Techniques

In order to make Vine-berg’s proposed operation successful, better diagnostic tools were needed. This was accomplished by the work

of Sones. He developed a diagnostic procedure, called “arteriography,” whereby a catheter was inserted into an artery in the arm, which he ran all the way into the heart. He then injected a dye into the coronary arteries and photographed them with a high-speed motion-picture camera. This provided an image of the heart, which made it easy to determine where the blockages were in the coronary arteries.

Using this tool, the team tried several new techniques. First, the surgeons tried to ream out the deposits found in the narrow portion of the artery. They found, however, that this actually reduced blood flow. Second, they tried slitting the length of the blocked area of the artery and suturing a strip of tissue that would increase the diameter of the opening. This was also ineffective because it often resulted in turbulent blood flow. Finally, the team attempted to reroute the flow of blood around the blockage by suturing in other tissue, such as a portion of a vein from the upper leg. This bypass procedure removed that part of the artery that was clogged and replaced it with a clear vessel, thereby restoring blood flow through the artery. This new method was introduced by Favaloro in 1967.

In order for Favaloro and other heart surgeons to perform coronary artery surgery successfully, several other medical techniques had to be developed. These included extracorporeal circulation and microsurgical techniques.

Extracorporeal circulation is the process of diverting the patient’s blood flow from the heart and into a heart-lung machine. This procedure was developed in 1953 by U.S. surgeon John H. Gibbon, Jr. Since the blood does not flow through the heart, the heart can be temporarily stopped so that the surgeons can isolate the artery and perform the surgery on motionless tissue.

Microsurgery is necessary because some of the coronary arteries are less than 1.5 millimeters in diameter. Since these arteries had to be sutured, optical magnification and very delicate and sophisticated surgical tools were required. After performing this surgery on numerous patients, follow-up studies were able to determine the surgery’s effectiveness. Only then was the value of coronary artery bypass surgery recognized as an effective procedure for reducing angina in heart patients.

consequences

According to the American Heart Association, approximately 332,000 bypass surgeries were performed in the United States in 1987, an increase of 48,000 from 1986. These figures show that the work by Favaloro and others has had a major impact on the health of United States citizens. The future outlook is also positive. It has been estimated that five million people had coronary artery disease in 1987. Of this group, an estimated 1.5 million had heart attacks and 500,000 died. Of those living, many experienced angina. Research has developed new surgical procedures and new drugs to help fight coronary artery disease. Yet coronary artery bypass surgery is still a major form of treatment.

See also Artificial blood; Artificial heart; Blood transfusion; Electrocardiogram; Heart-lung machine; Pacemaker.