Phthiraptera are obligatory, lifelong ectoparasites of birds and mammals. They are hemimetabolous and wingless, with dors-_JL oventrally flattened bodies, three pairs of well-developed legs, and a single- or double-segmented tarsus usually with one or two claws, but occasionally with claws absent. Ocelli are absent, eyes are reduced or absent, and antennae are short with 3-5 segments. Body length of adults ranges from 0.3 to 12 mm.

EVOLUTION AND DIVERSITY

Over 5000 louse species are recognized. Lice formerly were classified in two orders, Mallophaga (chewing lice) and Anoplura (sucking lice). However, they now are combined into the order Phthiraptera, with the former Mallophaga comprising three suborders (Amblycera, Ischnocera, and Rhynchophthirina) and the Anoplura a fourth. Although the suborders show substantial differences, they are believed to form a hemipteroid monophyletic unit whose sister group is the Psocoptera (psocids or topiclice). Chewing lice have mandibulate mouthparts and probably evolved on birds. They are thought to have fed initially on skin and feathers, with some groups ultimately expanding their diets to include tissue fluids and blood. Some chewing lice eventually made a transition from birds to mammals and some Ricinidae (Amblycera) have mouthparts adapted to pierce host skin.

Sucking lice are restricted to mammalian hosts and have unusual piercing-sucking mouthparts that consist of three stylets, probably derived from the fused maxillae, hypopharynx, and labium. The stylets, retracted into the head when not in use, are everted to pierce skin and feed on host blood. Salivary secretions injected into the host include an anticoagulant to prevent blood coagulation during feeding.

Lice are recorded from approximately 4500 bird and mammal species, encompassing about 27% of mammal species and 34% of bird species. As many as 50% of the extant louse species remain undescribed. Lice are found on all bird orders but are not known to be associated with the mammalian order Monotremata (monotremes), the marsupial orders Microbiotheria (the monito del monte) and Notoryctemorphia (marsupial “moles”), Afrosoricidae (tenrecs and golden moles), Chiroptera (bats), Cetacea (whales, dolphins, and porpoises), Sirenia (dugong, sea cow, and manatees), or Pholidota (scaly anteaters).

LIFE HISTORY

Details of louse life history are known for only a relatively few species, especially those of economic importance. Eggs (also known as nits) typically are cemented to hairs or feathers of the host and all life stages are confined to a single host. Some notable exceptions to this egg-laying behavior include the human body louse, Pediculus humanus humanus (Anoplura: Pediculidae), which attaches its eggs to clothing fiber and spends most of its time between feedings on clothing rather than on the host itself, and several genera in the chewing louse family Menoponidae (Amblycera) that spend their entire life cycles and deposit eggs inside the quills of primary and secondary feathers.

Immatures emerge from eggs by exerting pressure on an oper-culum at the free end of the egg. The timing and duration of the egg, three instars, and adult stages vary among species and may be affected by environmental temperature and humidity. Nymphs of the human head louse (P. humanus capitis) take 6-9 days to hatch and reach the adult stage in about 1 week. Adults remaining on the host live about 1 month, with each female laying as many as eight eggs per day. Immatures and adults normally feed twice each day and cannot survive off of the host for more than a few days.

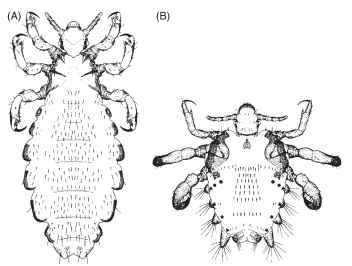

Dispersal of lice typically requires close contact between hosts, although immature lice have been found attached to flying insects that move between hosts, and phoresy may play a role in the dispersal of some species. The human body louse is dispersed by sharing infested clothing, the head louse (Fig. 1A) by personal contact or sharing combs and brushes, and the crab louse, Pthirus pubis (Anoplura: Pthiridae) (Fig. 1B), by sexual contact or, less commonly, through infested bed linens, towels, or clothing.

LOUSE-HOST SPECIFICITY AND COSPECIATION

Many lice show a high degree of host specificity, causing them to play an important role in studies of host-parasite cospeciation. For example, the 36 species of pocket gophers (Rodentia: Geomyidae) are parasitized by 122 species and subspecies of Geomydoecus and Thomomydoecus chewing lice (Ischnocera: Trichodectidae), many of which have distributions that conform closely to host-subspecies groups that are genetically similar. However, host specificity is not universal because many louse species occur on more than a single host species. Anatoecus dentatus and A. icterodes in the Philopteridae (Ischnocera), for example, each occur on more than 60 different species of ducks, geese, and swans (Anseriformes: Anatidae).

Many host species are parasitized by more than one louse species. For example, a single subspecies of brown tinamou, Crypturellus obsoletus punensis (Tinamiformes: Tinamidae), is infested by 11 species of lice, representing 10 genera in two families. When multiple louse species infest a single host individual, the different species may congregate in different areas of the body. In mammalian lice, habitat specialization often is associated with hair diameter. For example, the crab louse tends to be confined to the relatively coarse hair associated with the genital areas, the face, and the underarms, whereas the head louse tends to be associated with the smaller diameter hair of the scalp.

ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE

The economic importance of most louse species is unknown, although they are known to cause irritation, inflammation, and itching and serve as vectors of diseases and other parasites. High louse densities often are found on weakened or sick hosts, especially on birds with damaged bills or those unable to perform normal grooming activities. Lice infest a number of domestic animals including poultry, domestic dogs and cats, cattle, sheep, goats, horses, pigs,

FIGURE 1 Lice of humans (dorsal view of adult females). (A) Head louse, P. humanus capitis (Anoplura: Pediculidae), adult body length 2.1-3.3 mm (body lice look similar to head lice, but tend to be slightly larger). (B) Crab louse, P. pubis (Anoplura: Pthiridae), average adult body length about 1.75 mm for females and 1.25mm for males.

and rabbits. Animals in zoos and laboratory colonies of rats and mice also may become infested. Economic loss to the livestock and poultry industry in the United States caused by lice has been estimated at more than $550,000,000 per year, with about two-thirds of this resulting from weight and egg production losses in poultry caused by chewing louse infestations.

The human body louse serves as the vector of epidemic typhus and epidemic relapsing fever and as an occasional vector of murine typhus. Epidemic louse-borne typhus, a rickettsial disease caused by Rickettsia prowazekii, is an important scourge of humans often associated with wars and disasters. It still is endemic in cold areas of Africa, Asia, and Central and South America. Zinsser gives a remarkable account of the impact of this disease on human history. For example, the disastrous failure of Napoleon’s Grand Armee to conquer Russia during the campaign of 1812 is attributed largely to the effects of epidemic louse-borne typhus fever combined with malnutrition, dysentery, and exposure. The effectiveness of the pesticide DDT was demonstrated in 1943 during World War II in the control of lice responsible for an outbreak of typhus fever after the Allied bombing of Naples, Italy.

The name typhus is derived from Greek typhos, meaning stupor or fever. Infected humans experience high fever often accompanied by severe headaches, mental confusion, chills, coughing, and muscular pain. A rash generally appears on the 5th to 6th day and usually spreads to much of the body except the face, palms, and soles of the feet. The mortality rate usually is 1-20%, but can be much greater under epidemic conditions in populations that are weakened by malnutrition or other diseases. Transmission is by contamination of wounds with louse feces rather than through the bite or feeding of the louse. Brill-Zinsser disease is a relatively mild form of typhus that can remain viable in humans for years and can serve as a reservoir of the disease and the source of future epidemics. Although not associated with disease transmission, outbreaks of the human head louse are epidemic throughout the world, with treatment complicated by the development of louse resistance to some commonly used chemical control agents.

CLASSIFICATION AND HOST ASSOCIATIONS

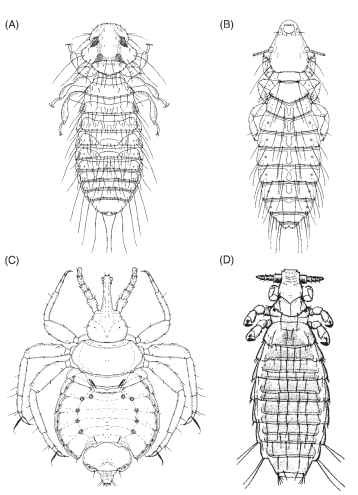

Amblycera is regarded as the most primitive louse suborder, and the Rhynchophthirina and Anoplura are thought to be the most advanced. The suborder Amblycera (Fig. 2A) includes six families: Boopiidae (mostly on marsupials, with one species infesting dogs and another the cassowary), Gyropidae (mostly on rodents, but with one genus occurring on New World monkeys and another on peccaries), Laemobothriidae (found on six bird orders), Menoponidae (widely distributed on birds), Ricinidae (on passerines and hummingbirds), and Trimenoponidae (on marsupials and rodents). The suborder Ischnocera (Fig. 2B) includes two families: Philopteridae (widely distributed on birds, with two species on primates, one on lemurs and the other on the indri) and Trichodectidae (on seven mammalian orders). The suborder Rhynchophthirina (Fig. 2C) contains a single family, Haematomyzidae, found on elephants, wart hogs, and the red river hog. The suborder Anoplura (Fig. 2D) includes 15 families, all restricted to mammalian hosts: Echinophthiriidae (on seals, sea lions, the walrus, and the North American river otter), Enderleinellidae (on squirrels), Haematopinidae (on horses and their relatives, pigs, cattle, and deer), Hamophthiriidae (on flying lemurs), Hoplopleuridae (on 8 families of rodents, a few shrews, and one species of pika), Hybophthiridae (on the aardvark), Linognathidae (on deer, cattle and their relatives, camels, and dogs and their relatives),

Microthoraciidae (on the llama, alpaca, guanaco, and dromedary), Neolinognathidae (on elephant shrews), Pecaroecidae (on peccaries), Pedicinidae (on Old World monkeys), Pediculidae (on humans, chimpanzees, and New World monkeys), Polyplacidae (on 13 families of rodents, shrews, tree shrews, hares, and 5 families of primates), Pthiridae (on humans and gorillas), and Ratemiidae (on horses and their relatives).

There is disagreement as to whether the human head louse should be recognized as a distinct species (Pediculus capitis) or as a subspecies of P. humanus (P. humanus capitis). Those favoring its recognition as a separate species cite differences in behavior, size, coloration, and ability to transmit disease. Those favoring subspecies

FIGURE 2 Louse suborders (dorsal view of adults). (A) Amblycera: Colpocephalum fregili (Menoponidae), male from the red-billed chough (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax). (Adapted “rom Price and Beer. (1965) Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 67, 7-14.) (B) Ischnocera: Quadraceps crassipedalis (Philopteridae), female from the least seed-snipe (Thinocorus rumicivorus). (Adapted from Emerson and Price, 1985, Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 87, 395-401.) (C) Rhynchophthirina: Haematomyzus porci (Haematomyzidae), male from the red river hog (Potamochoerus porcus). (Adapted from Emerson and Price, 1988, Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 90, 338-342.) (D) Anoplura: Polyplax spinulosa (Polyplacidae), female of the spiny rat louse from the Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus).

recognition note that populations of head and body lice are separable only statistically on the basis of minor differences in body size; that coloration in human lice is highly variable, with lice often taking on the color of their surroundings; and that hybridization between head and body lice has been demonstrated in the laboratory and is thought to occur in nature.