Quality photography of small animals in the field depends on rapid response to opportunities; this requisite is often impeded by the need to constantly root around in overstocked camera bags for the “right” piece of equipment. This article describes the author’s personal approach to insect photography, which is to improvise with as little gear as possible. If it does not fit comfortably in your backpack, why have it at all? This philosophy may not be relevant to the intended audience of most insect photography essays, namely, the museum curator, studio photographer, artist, or laboratory scientist, who have time to “set up” a picture. Specific brands are not considered here. In part this is because the market is in flux with the ongoing technological shift to autofocus and digital cameras and, in part, because the quality of lenses produced by any of the major camera lines today is sufficient to produce excellent photographs. Expensive gear is not a necessity for the best results.

For all but the largest insects or insect-produced structures such as nests, capturing insects on film typically requires macrophotography, which is photography at a magnification of 1:1 (“life size”) or greater, which is the focus of this article. At 1:1, subjects are the same size on the film as they are in life. That is, the image of a 30-mm-long beetle measures 30 mm in length on the film negative or slide, which means it fills most of the frame in a photograph on 35-mm film. For a 3-mm beetle to appear just as large (i.e., so that it is likewise 30 mm in length on the film) requires 10 times life-size magnification, which is typically described as ” X10,” or 10:1. The measurements are taken from the original film exposed in the camera, so prints made from a negative or slide would enlarge the subject beyond this size. For example, a 35-cm-wide print of the 3-mm-long beetle at X10 on 35-mm film shows the beetle 30 cm in length, or 100 times its natural size.

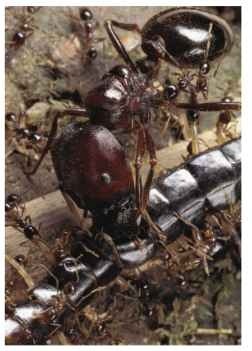

One of the wonders of a well-executed insect photograph is that the subject’s original size is forgotten: the small beetle is just as imposing as the large one. This actually makes photography a wonderful medium for entomologists. Not realizing this, photographers often concentrate on insects that are impressive merely for their size. In fact, when not photographed on the photographer’s hand, many large insects can look small on film. Similarly, elephants may be spectacular in life, but on film we can only make one appear smaller than it really is. I recall my mentor at National Geographic, editor Mary G. Smith, taking her first look at my first “macro” images in 1986 (Fig. 1), which were photographs of marauder ants killing prey. She exclaimed that

FIGURE 1 An 8-mm-long major worker (“soldier”) marauder ant, Pheidologeton diversus, killing a centipede that has been pinned down by numerous smaller minor worker ants in Malaysia.

they reminded her of the movie “Terminator,” even though the ants looming over doomed prey in my pictures were just a few millimeters long. A criterion for a good insect photograph is that viewers are as surprised as Mary when a subject’s size is revealed.

LENSES

Although regular lenses can be used in combination with other equipment to produce images of life size or greater, for example, by adding extension tubes or magnifying filters, the results can be inferior to the photographs made with standard ” macro lenses. ” Although the term “macro” has been watered down in recent years by its application to lenses that focus relatively closely to the subject, true macro lenses focus all the way to 1:2 or 1:1 (sometimes an extension tube may be required for 1:1). These macro lenses are the sharpest, most optically corrected lenses produced by most companies and thus can be a wise investment. Many of them (typically those with focal lengths of about 50, 100, or sometimes 200 mm) can also be used as regular lenses, in which case they completely replace any other lens of a similar focal length. It should be noted that some of the optical precision of macro lenses relates to their having a “flat field” of focus. This characteristic is seldom important when working with live insects, unless perhaps one is in the habit of photographing straight down on flat insects living on the kitchen floor. Thus, when used with care, some less expensive lenses may be just as good in the field as true macro lenses, even when used at magnifications as high as 1:1.

A constant problem in insect photography is the distance from the front of the lens to the subject. With a macro lens set to a high magnification this distance may be only a few millimeters, so it takes practice not to disturb the insect when preparing to take a picture. In this regard stalking an insect is little different from stalking a leopard or a deer. As one moves the camera until the quarry comes into focus, one can learn to recognize through the viewfinder the moment when an insect detects the photographer. Each insect can require a different stalking technique.

If a short working distance causes the subject to be knocked or startled, the photographer should shift to a longer focal-length lens. A 200-mm macro lens provides a much greater working distance than a 50-mm macro set to the same magnification. Yet the longer lens is likely not to be quite as sharp, is harder to hold steady enough to focus precisely, requires heftier (and more unwieldy) brackets to hold the flashes, and needs more extension tubing to achieve magnifications beyond 1:1. If one can handle its short working distances, a 50-mm lens is therefore the ideal macro, but the 100-mm lens comes a very close second.

To achieve magnifications beyond life size with standard macro lenses, extension tubes are placed between a lens and the camera mount. Bellows are a more flexible alternative to tubes, because they provide every conceivable magnification between some upper and lower limit, but they are unwieldy and fragile in the field. The fixed lengths of the tubes are seldom a liability outdoors where being able to quickly frame and shoot insects is more important than precise cropping. In fact, tubes shorter than about 25 mm generally have little value with macro lenses because their effect on magnification is so slight.

In addition to standard macro lenses some manufacturers offer lenses designed exclusively for macrophotography (e.g., the X1 to X5 zoom lens made by Canon). Most of these lenses are built for high magnifications. An article by the author on soldier aphids in 1989 (Fig. 2) contains images between X5 and X20 on the film taken with a hand-held camera in the field. Whereas a standard macro lens

FIGURE 2 Soldiers of the aphid Pseudoregma jamming their needlelike “horns” into the cuticle of a syrphid fly larva that was attacking their colony in Japan.

can be used with only two or three extension tubes before working distance becomes too small to be practical or image quality declines, with some of these specialized lenses it may be possible to use several tubes at once.

Rotating the lens barrel either manually or with autofocus accomplishes focusing in normal photography, but it changes the magnification of an image in macrophotography, making it difficult to achieve the desired results. Autofocus therefore should be disengaged. Instead, focusing must be done as a manual, multistep process. Begin by deciding what magnification is desired, based on a subject’s size. Select the lens and extension tubes needed to achieve that magnification. Then aim the camera toward the subject, rocking slowly in and out until the subject appears in focus.

Photographs at the highest magnifications require a steady hand, a sharp eye, and a lot of practice. Each photographer needs to understand his or her own limits from experience. The problem is not only in seeing and composing the shot but also in the limited depth of field at higher magnifications. The depth of field is the depth (from front to back) that appears in focus within an image. All the significant parts of the image must fall within this area for a photograph to make sense. At times the author has used a half meter of extension tubing in the field, and in these situations the depth of field can be the length of a paramecium! To increase the chance of success, take a few images after focusing on the subject by rocking back and forth slightly to subtly change the plane of focus each time.

As in all high-magnification photography, automatic film advance comes in handy not so much to allow rapid-fire picture taking but to allow one to keep a subject correctly framed and in focus while these frame-to-frame shifts in the film plane are made. Another aid is to use a flashlight, even at midday (illuminate crevices and other small shadows or the shadow of the lens itself). Using Velcro, tape, or glue, attach a small penlight to either the lens or one of the flashes so that it can be aimed at the subject. Camping stores have many flashlights that can work. It is best to bring in a camera and try out specific designs.

FLASHES

It is possible, but seldom advisable, to photograph a large insect with natural light using a tripod. With sufficient photographic skill, any image of an insect can be improved by the addition of flashes. Flashes provide a consistent and high quality of light, though flashes with colder (bluer) light can be improved by leaving a “warming gel,” like a Kodak CC10Y filter, taped over the flash window (one layer of frosted scotch tape can by itself sometimes do the trick). Flashes freeze any motion of the subject or camera—including most importantly any motion caused by the trembling of the photographer’s hands—and do so far more effectively than a tripod (particularly at high magnification). Furthermore, in the time it takes to set up a tripod, most insect subjects will have moved on to greener pastures. Flashes allow one to move in quickly and to constantly adjust the angle of approach as the action unfolds. For these reasons, the author seldom carries a tripod and even then never for macro work. Nonetheless, views of large insects in their environment, often at a high aperture with a wide-angle lens focused on a close subject, can be taken using natural light and a tripod, though with ground-or bark-dwelling species the camera may be steadied sufficiently by pressing it firmly against the stable substrate.

Not only can flash light increase the quality of any insect photograph, but when used with skill, two flashes are always an improvement over one flash, and two regular flash units are always an improvement over any method using a ring flash. The second flash serves as a “fill light,” that is, it is weaker (usually one-half the strength or one stop weaker) than the other, “main flash.” A fill-flash results in photographs with nicely defined, pleasant shadows and lots of three-dimensional information about the subject. The fill flash can be a weaker flash model, but often it is the same kind of flash placed at the same distance as the primary flash, but set at a lower power output or filtered to reduce the light (a sheet of tissue or artist’s tracing paper over the fill-flash head can do the trick). The flashes should be aimed toward the subject at about 45° from the axis of the lens and positioned anywhere from 90 to 120° apart around the lens barrel. For insects on reflective surfaces such as flowers and bright leaves, the light bounces off the surfaces and “fills” shadows somewhat, reducing the necessity of a fill flash. For shooting under these conditions, a single flash method as described by Shaw may suffice.

Ring flashes present problems with insects. The lower part of the ring impedes one from shooting low to the ground, blocking the most dramatic views. Also, the ring projects forward beyond the front of the lens all around the circumference, reducing the working distance. Further, because their light circles the lens and is directed forward rather than angled at the insect, ring flashes reduce the image’s three-dimensional content, making a subject look relatively shapeless and flat (ring lights were developed for flat objects such as stamps). This problem can be partially remedied by taping over parts of the ring. On the positive side, ring flashes provide good color saturation for photographers unsure of their photographic technique, especially when they are used in combination with a fill light.

The greatest stumbling block to great macrophotography is the scarcity of good two-flash systems. Some flash brackets have been marketed, but most are bulky (making it hard to photograph in the tight corners, where many insects dwell), are difficult to hold steady for long periods because of their weight, and are easily knocked out of position in the field. The author makes his own systems, from various flashes, power packs, brackets, cords, and slaves. Because flashes can be used in their nonautomatic (manual) settings, items from various camera brands can be mixed to achieve the lightest, most compact results with the flashes at optimal positions. Camera brands must be mixed with care, for example, by taping over flash shoe connections if flashes of one brand are used with a camera body of another brand. No design is perfect, but some are better than others, and all of them can be modified.

The position of the flashes is most critical. When a small flash head is even a few centimeters away from the insect, viewed from the subject’s position it appears as a point of light—much as the sun (although it is in fact a huge disc) appears as a point in the sky because of its distance from us. This kind of “point source” of light causes the most intensely illuminated spots to be “burned out” (too bright) and casts deep shadows that no film can handle (as occurs with any sunlit object on a cloudless day). To avoid such problems flashes should be placed as close to the subject as comfortably possible. So positioned, the lights resemble the light boxes used in studio photography for portraits. What is desired, in fact, is to replicate such a studio in miniature. One can even add a third light traditional in portrait studios, the “hair light,” that is aimed from behind to define the edges of the subject, but for most field photographers this light is often unnecessary.

SHARPNESS AND EXPOSURE

Achieving a sharp, correctly exposed macro image usually takes knowledge that comes from testing the system being used. Exposure tables and other text topic information are seldom accurate and are no substitute for judging for oneself what is pleasing. Tests that are done carefully the first time will never have to be done again—good results are guaranteed.

Light meters are not always effective with many macro scenes, which often include objects that can be either black or brightly lit depending on slight changes in camera position relative to the subject and its background. For this reason, manual exposure techniques provide greater accuracy, but if a camera meter is preferred, these problems in a scene must be recognized and exposure bracketed accordingly. The best flashes for manual exposure work have multiple manual settings, that is, full power, half-power, quarter-power, and so on.

To test both the flashes and the lens and to develop a technique, select a fine-grained slide film (many with an ISO of 100 or less work well). Slides allow one to accurately gauge the exposure and sharpness of the images. As a test subject, put a dead insect of a kind likely to be photographed on an 18% gray card (available at most major photography stores). Then take a series of test photographs, recording magnification, flash position, flash power, and f-stop for each frame of the film as follows:

1. Set the lens so that it gives a certain magnification (say, 1:1) or has a certain number of tubes that can be remembered (say, one 25-mm tube).

2. Select the power settings of the two flashes (perhaps put one on full power and the fill flash on half-power).

3. Take a series of photographs of the insect on the gray card at a standard angle (say about 45° from the horizontal), the first at the lens’ minimum aperture (say, f32) and then at one-f-stop intervals below that, down to f8.

4. Select another set of power settings for the flashes, say making both of them one stop weaker (i.e., one at half-power and the other at quarter-power).

5. Repeat steps 2 and 3 with weaker flash power settings.

The developed slides should be checked for image detail (such as the texture of the gray card and the sculpturing on the insect) and

exposure (have the original gray card on hand to see if the brightness of the slide matches the gray of the card). Pick the combination of flash powers and f-stop that gives the most pleasing result (see below). That result might be, for example, f22 with the flashes set at half- and quarter-power (but if f22 looks a bit too dark and f16 looks too light, record the intermediate setting as correct, i.e., f18). Write the settings down and use them thereafter for that magnification (although, as in any photographic situation, one can bracket slightly, for example, by opening up to f16 when the subject or its background is very dark). If it turns out the test photographs are all dark, move the flashes closer or purchase stronger units. If they are all too bright (or if the correct exposure occurs at an f-stop that has too little depth of field, as is explained below), weaken both flashes and test again.

Results from the first magnification can be used as the starting point for testing other magnifications, because results tend not to differ radically from one magnification to the next. For example, try a series of magnifications such as X2, X3, and X6 (or, if preferred, the same lens with 50, 100, and 200 mm of lens tubing). After working out the correct exposure for each magnification, write up an exposure table and tape it to the back of the flash heads for reference.

Most people choose images that are overexposed (i.e., too bright), which for macrophotography means that valuable flash battery power has been wasted in producing too much light. If in doubt, choose a slightly darker image over a slightly bright one. To correctly judge exposure and image quality use a color-corrected (5500 K) light table and a photographer’s loupe. For slide film the highlights (bright parts of the image) should not be entirely burnt out except perhaps for tiny areas, and the colors over most of the image should be saturated (richly hued and not faded by strong light). Meanwhile, the darkest parts of an image should be inky black, but not so much as to lose detail by rendering an image blotchy. If burnt areas or blotchiness occur, try repositioning the flashes.

The tests may show the classic trade-off in macrophotography between depth of field and image quality. Thus, even though most macro lenses tend to close down to 32 and this f-stop provides the most depth of field, to produce sharp images it is best to open the aperture at least one stop from this setting (in this example, f22). The best quality—highest resolution and contrast—may actually occur at a stop lower that that (e.g., at f16), but the difference may be marginal enough so that the best choice is to use f22 because of the greater depth of field it provides. If a lot of extension tubing is added to a lens, image quality for the same f-stop setting on the lens may drop further, perhaps to an aperture of f11. This adjustment is a problem because the depth of field also declines as extension tubes are added or magnification is otherwise increased. Therefore the highest magnification attainable by a lens depends on the accuracy of the photographer with focusing and the optical limits of that lens. At some point, it becomes necessary to purchase a lens better designed for the magnification in question.

TECHNIQUE

The most difficult subjects require considerable patience and a lot of time—sometimes a hundred attempts for every usable image. Ways of improving one’s chances can be found, such as having on hand a supply of food items in photographing predation, but such techniques must be used with care. Usually, the best image results from capturing the animal in the act of normal behavior in its normal habitat. This image is “best” not necessarily because of its technical perfection (on the contrary, the gritty realism of a slightly imperfect image sometimes enhances its drama, as is often true in photojournalism), but because of its accuracy. For example, a knowledgeable person might detect that the prey provided to the subject for a photograph is not a species that it normally would find and catch. Even more egregious is the refrigeration of specimens to slow them down for a picture. Despite their stiff exoskeletons, insects express themselves by subtle postures and actions (see Fig. 1). To the expert, a staged picture of a chilled insect appears as unnatural as one of a frozen human being.

With time and experience, one may want to attempt a photoessay or lecture on a particular subject. To hold a viewer’s interest, try to incorporate a variety of compositions and magnifications. A critical overview of nature photojournalism was provided by Moffett in a 1995 article.