The ubiquity of insects and the frequency of their interactions with humans virtually ensure that they will feature prominently in cultural contexts. Throughout history, insects have conspicuously appeared in a range of visual media, including painting, sculpture, printing, and engraving. Thus, with the advent of film in the late-19th century, insects were depicted in some of the earliest efforts; since then, they have made appearances in virtually every form of this modern medium. As the 21st century begins, insect images are common in film and television, and their role in cinema is firmly established. In fact, their impact on culture has been so pronounced that references to insect movies even serve on occasion as punch lines in jokes and cartoons, and the expressions “big bug film” and “insect fear film” are widely recognized.

THE TAXONOMY OF CINEMA

What constitutes an insect in cinema is not necessarily consistent with scientific standards. In the taxonomy of cinema, any jointed-legged, segmented organism with an exoskeleton is likely to be classified as an insect, irrespective of how many legs or how few antennae it possesses. For example, in Sherlock Holmes and the Spider Woman, Holmes identifies a spider (used by the Spider Woman to dispatch her victims) as Lycosa carnivora from the Obongo River in Africa, the ” deadliest insect known to science” ; in actuality, spiders are classified as arachnids and not as insects. Taxonomic categories are also ill defined in cinema; in the film

Tarantula , for example, the artificial-nutrient-enhanced giant spider is identified as being “from a species called Arachnida—a tarantula, to be exact.” The taxon Arachnida is not a species; rather, it is a class, containing thousands of species. In Mimic, the eminent entomologist Dr. Gates, mentor of a young scientist engaged in genetic engineering experiments with cockroaches, makes reference to the “Phylum Insecta.” Again, “Insecta” is the name of the taxonomic unit called a “class”; the phylum to which insects belong is Arthropoda.

Insect morphology in the movies reflects the relatively sketchy familiarity most filmmakers have with entomological reality. As is the case for real-life insects, most movie insects have six legs, whereas movie arachnids often have eight. In general, movie insects also have the three characteristic body regions—head, thorax, and abdomen— that differentiate them from other arthropods. Even at the ordinal level, many morphological features are depicted with some degree of accuracy. Movie mantids can have raptorial forelegs (e.g., The Deadly Mantis), and movie lepidopterans (e.g., Mothra, the giant moth that attacked Tokyo in a series of Japanese films from the 1960s) possess scales. Large flat objects of the size of pie plates scattered around the countryside (eventually identified as oversize scales) provide evidence of an enormous moth in The Blood Beast Terror.

Other aspects of insect anatomy, however, are not so accurately portrayed. Compound eyes are cause for some confusion; many films present an “insect-eye” view of a particular scene (usually a victim-to-be) through a filter lens, to simulate what is imagined to be the image created by compound eyes (e.g., in Empire of the Ants). In reality, these images appear to insects to be more like mosaics than repeated images. In Monster from Green Hell, the compound eyes of the cosmic wasps roll in their sockets; real compound eyes are incapable of such motion. Antennae are also poorly understood anatomical features; on occasion, movie arachnids are equipped with a pair, even though antennae are lacking in real-life arachnids (e.g., the 1973 animated Charlotte’s Web) . Not surprisingly, mouthparts (whose intricacies in real insects are rarely visible to the naked eye) in movie arthropods often bear little resemblance to real arthropod mouthparts.

Insect physiology in movies often bears only a passing resemblance to the physiology of real arthropods. According to Dr. Elliot Jacobs, the entomologist in Blue Monkey who assists in attempting to control an outbreak of genetically engineered mutant cockroaches in a hospital, “Insects aren’t like humans or animals. They’re 80% water and muscle. They have very few internal organs.” A recurring conceit in insect films is the violation of the constraint imposed by the ratio of surface area to volume—movie arthropods routinely grow to enormous size without suffering the limitations of tracheal respiration or ecdysis and sclerotization experienced by real-life arthropods. Nonetheless, there are physiological attributes of film arthropods that are reproduced with some degree of fidelity. Insect pheromones figure prominently in insect fear films (although they are not always identified as such; in The Bees they’re called “pherones”). In Empire of the Ants, for example, giant ants use pheromones to enslave the local human population and to compel the humans to operate a sugar factory for them. The explanation provided for the response is that a pheromone “causes an obligatory response—did you hear that? Obligatory. It’s a mind-bending substance that forces obedience….” Although they have long been documented to exist in a wide range of organisms (including humans), pheromones rarely appear in science fiction films outside an entomological context.

As is the case with insect physiology and morphology, insect ecology takes on different dimensions in the movies. Life cycles are unorthodox and generally dramatically abbreviated by entomological standards. In Mosquito, for example mutated mosquitoes, the offspring of normal mosquitoes that had consumed the blood of aliens in a crash-landed UFO, have a life cycle consisting only of egg and adult stages. In Ticks, full-grown ticks eclose from what seems to be a cocoon. Population dynamics differ as well. A number of movie arthropods seem to have a population size of one (as evidenced by the titles—e.g., Tarantula, The Deadly Mantis), and reproduction does not seem to occur (at least over the 2-h span of the movie). At the other extreme, populations often build up to enormous sizes without depletion of any apparent food source. Bees blacken the sky in The Bees and The Swarm in a remarkably short period of time with no superabundance of nectar sources in evidence. It must be assumed that food utilization efficiencies of virtually all film arthropods are far higher than they are in real life because arthropods in films, giant or otherwise, rarely produce any frass (e.g., in Beginning of the End, giant grasshoppers consume several tons of wheat in a 3-month period with little or no frass to show for it). In Starship Troopers, it is unclear what the giant arthropods living on a planet that is bereft of other life-forms eat to attain their large size. However, because they are alien arachnids, terrestrial biological standards may not necessarily be applicable.

Insect behavior in big bug films is often biologically mystifying. Screen insect predators and herbivores alike almost invariably announce their presence with an ear-piercing stridulating sound (e.g., Them, The Deadly Mantis, Beginning of the End, Empire of the Ants); in reality, such behavior would alert prey to danger and elicit escape or defensive behavior (which, on the part of humans in many films, involves machine guns and bazooka fire directed at the insect). For example, in Beginning of the End, a television newscaster updates viewers in Chicago on the Illinois National Guard’s efforts against hordes of gigantic radiation-induced mutant grasshoppers descending on the city, reassuring them that “the one advantage our forces hold over the enemy is that they ALWAYS reveal their intention to attack. Before every attack the locusts send forth this warning in the form of a high-pitched screech. Now, this screech increases in intensity until it reaches ear-shattering proportions. And it’s when this screech reaches its full intensity that the locust attacks.” Such maladaptive behavior is unlikely to persist in nature.

INSECTS IN ANIMATED FILMS

Until the mid-20th century, insect representation in cinema was restricted largely to animated films. The small size of insects presented challenges to the standard equipment of the time that could not be met without either a disproportionate increase in cost or a decrease in visual quality. In animated films, however, technical limitations could be avoided; to create the illusion of a close-up, the animator can simply draw a larger image. In animated films, one or two frames are exposed at a time, and between exposures small changes are introduced; for example, one drawing may be substituted for another slightly different drawing or a puppet or clay model slightly repositioned. When the film is projected at normal speed, the image appears to move. An insect may even have inspired one film pioneer to become one of the first animators. Segundo de Chomon, a Spanish filmmaker of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, allegedly conceived of the animation process while shooting intertitles for a silent film and noticing that a fly, included on the footage exposed a frame at a time, appeared to move in a jerky fashion when the film was projected.

This is not to say that insects were not a challenge to animators. Because of their many moving body parts—six legs, two antennae, and from two to four moving wings—many animators simplified their drawing by reducing appendages. Thus, in animated films, insects may be depicted with four instead of six legs and spiders with six instead of eight. The first appearance of an insect in an animated cartoon was in a 1910 film by Winsor McCay titled How a Mosquito Works—the second American animated cartoon. Although McCay accurately portrayed his mosquitoes with six legs and two wings, in contrast with later animated films featuring insects with reduced appendages, even this early film contains many of the other conventions typically found in insect cartoons—an adversarial relationship between humans and insects, as well as the depiction of insect mouthparts as tools. McCay showed the film in vaudeville houses to large crowds and later returned to the use of insect characters with his 1921 film Bug Vaudeville.

Another very early example of puppet animation was provided by entomologist-turned-animator Wladislaw Starewicz. In attempting to film the mating behavior of stag beetles, Starewicz discovered that the hot lights used to illuminate his subjects caused them to stop moving altogether; accordingly, he killed and dismembered the beetles and wired their appendages back onto their carcasses, painstakingly repositioning them for sequential shots in the short film The Fight of the Stag Beetles. That film and its fictionalized sequel, Beautiful Lucanida or the Bloody Fight of the Horned and the Whiskered, proved to be quite popular with audiences. Starewicz expanded his efforts, eventually abandoning real insects and constructing puppets de novo for his later films with more complex plots (as in Revenge of the Kinematograph Cameraman, a story of love and betrayal among a variety of insect species).

Arguably the most well-known animated arthropod was Jiminy Cricket, who initially appeared in a supporting role in the 1940 Walt Disney feature Pinocchio. Disney animators used a talking cricket, a minor character that appeared in the original Pinocchio story by Carlo Collodi, to unify disparate elements within the film. The character proved to be popular as a “voice of conscience” and appeared in several series of subsequent short subjects and educational films. Jiminy exemplifies the liberties taken with insect morphology by animators; although early sketches depicted the character with more insect-like features, the final film version, with its two arms and two legs, eyes with pupils, and morning coat and vest, resembles a dapper elf more than any arthropod.

Computer animation developed at a rapid pace during the 1980s and has proved particularly well suited to depicting insects. Modern methods of computer-generated imagery (CGI) have become particularly effective at creating shiny metallic surfaces and at joining slender rodlike structures to larger volumes—precisely suited to depict an insect’s exoskeleton and multiple appendages. The first computer-animated insect was Wally-Bee, in the 1984 short film from Pixar titled The Adventures of Andre and Wally-Bee; this film was the first computer-animated short film with a plot line. That CGI offers technological advantages over traditional animation is not to say that it has resulted in more realistic animated insects. A Bug’s Life (1998) from Disney/Pixar continued to depict insects with anthropomorphized faces and four limbs to ensure audience empathy with the characters; the DreamWorks film AntZ (1998) gave its ants six legs but provided them with similarly humanized faces and raised the head and thorax into a vertical position, making them look like tiny centaurs. CGI is not limited to what is basically caricature, however; the otherwise live-action Joe’s Apartment (1996) featured hundreds of computer-rendered cockroaches which were indistinguishable from the real thing, except for their ability to sing and dance.

INSECTS IN FEATURE FILMS

Big Bug Films

Frequent appearances by insects in live-action films are a relatively recent phenomenon in the history of film. For many years,the technical challenges of filming very small, largely untrainable, fast-moving creatures was a disincentive for incorporating them into films. The pioneering efforts of special-effects genius Willis O’Brien, starting in the 1930s, and of his protege Ray Harryhausen, as well as technical advances in the production of film stock and traveling matte techniques, gradually made the incorporation of insect images in film economically attractive, or at least reasonable. Moreover, competition for audiences, particularly with the rise of television, led the major film studios to increase investment in hitherto minor genres, such as science fiction. With bigger budgets, more elaborate effects became feasible.

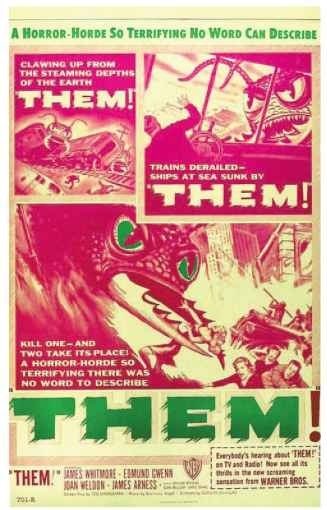

The year 1954 was a watershed year; Them! was released by Warner Brothers Studios, featuring giant ants mutated by exposure to atomic testing in the Arizona desert (Fig. 1). The film, tapping into widespread fears of atomic power in the aftermath of World War II,

FIGURE 1 Lobby poster from the science fiction classic Them! (1954), noted for its dramatic special effects and suspenseful screenplay. The film depicted an attack on the city of Los Angeles by ferocious giant ants, mutated to greater than human size by radiation exposure. Made during the height of the 1950s Red Scare, Them! attracted large audiences with its ability to link the imaginary threat of gigantic, murderous insects with America’s real fears of nuclear fallout, foreign invasion, and scientific manipulation of the natural world.

was an enormous success, grossing more money for the studio that year than any other and winning an Academy Award for special effects. Its success is understandable in retrospect: its use of large mechanical models was innovative and dramatic, its screenplay was tight and well written, it featured several big-name actors of the era, and its subtext about invasion disrupting the fabric of American life played well to American fears of communist powers.

The “big bug films” inspired by the success of Them! were by and large lesser efforts. Many of these were the work of director/ producer Bert I. Gordon, who made so many films with big animals that he was known as “Mr. Big” (a reference as well to his initials— B.I.G.); his big bug films included Beginning of the End (1957), featuring giant radiation-induced grasshoppers threatening to destroy Chicago, and Empire of the Ants (1977), about giant radioactive-waste-induced ants threatening a real estate development in Florida. Other notable titles of the 1950s in the “big bug” genre (Table I) include Tarantula, The Deadly Mantis, The Black Scorpion, Monster from Green Hell, and Earth vs the Spider. The Japanese film industry did not embrace this genre until the 1960s but made up for the slow start in volume; the first Japanese big bug film, Mothra, featuring a giant radiation-induced moth, was released in 1962 and was followed by four sequels, in which Mothra appeared with other “big” science fiction stars such as Godzilla and Rodan.

Transformation/Metamorphosis Films

Metamorphosis is a characteristic of a substantial proportion of movie arthropods, although the film version is often at variance with reality. The transformation most frequently depicted in films is insect to human or human to insect, generally involving some form of exchange of body fluids—”Drosophila serum” in the case of She Devil (which allows the patient to transform herself at will from brunette to blonde), “spider hormones” in Mesa ofLost Women, “royal jelly” in Wasp Woman, and “DNA” in the 1986 remake of The Fly. Insects most likely appear frequently in films involving metamorphosis because of the shock value—the transformation of a human into a life-form radically different in appearance. Generally, transformations of humans into other animal forms in films involve magic or reincarnation (The Shaggy Dog, The Shaggy D.A., Oh, Heavenly Dog, Lucky Dog) or genetic predisposition (Teen Wolf and its sequels, The Howling and Cat People) rather than mediation by hormones (with the exception of the early films of Bela Lugosi, including The Ape Man and Return of the Ape Man, which involve serum exchanges between humans and apes).

In the 1980s, insect fear films acquired a new life with the release of David Cronenberg’s The Fly. Although as scientifically as inaccurate as earlier efforts with respect to surface area/volume rules, it was generally regarded by critics as an artistic success, thematically depicting physical transformation leading to mental and emotional change. Although The Fly II (directed by Chris Walas, special-effects artist on the earlier film) was not embraced as enthusiastically by critics, it nonetheless was perceived as more than just a horror film, with allegorical elements relating the physical and emotional changes of adolescence with the metamorphic transformation of the protagonist. Despite the presence of redeeming intellectual content in these films, these films attracted considerable attention for their graphic special effects, far surpassing earlier efforts.

In 1983, the first report of successful genetic transformation of an insect (Drosophila melanogaster) was published, and by 1987 genetically engineered insects (specifically, mutant killer cockroaches) made their first appearance in a science fiction film, in the otherwise unremarkable film The Nest, Genetic engineering techniques advanced more quickly on screen than in real life; by 1997, in Mimic, the young entomologist Susan Tyler (Mira Sorvino) is able to incorporate termite and mantid DNA into cockroaches, with the goal of creating a “Judas bug” to bring contagion to the cockroach vectors of a human illness but instead unleashes a plague of 6-foot-tall people-eating cockroaches in the subway system of New York City. In Spiders, unspecified alien DNA is incorporated into the titular arthropods to wreak havoc in a secret government laboratory.

“Social” Insect Films: Small Size, Large Numbers

One of the largest orders of real-life arthropods, the Hymenoptera, is in fact the most frequently depicted in insect fear films. There may be several reasons for this proportional similarity. For example, bees are relatively easily manipulated for the camera in comparison with other insects, can be produced commercially, and can be reared in enormous numbers with comparative ease. Perhaps an even more important factor, however, is their familiarity to the audience. Encounters with bees, ants, and wasps are part of the normal course of life for most moviegoers. Such an explanation also can account for the proliferation of films involving cockroaches, although these, too, share the practical advantage of ease of rearing in enormous numbers and affordability.

Films using footage of real insects engaging in more or less normal insect behaviors rose to prominence in the 1970s and included such efforts as Phase IV, featuring documentary-quality footage of ants, and Bug, featuring Madagascar hissing cockroaches (albeit engaged in some unusual behaviors, such as spelling out death threats with their bodies on the wall of a house). The appearance of African “killer” bees on a container ship in San Francisco harbor in 1974 may have inspired filmmakers to capitalize on a real threat— the introduction of African honey bees whose heightened aggression can cause problems for pets, livestock, and humans. The films proved popular with filmmakers in part because audience members enter the theater with at least passing familiarity with the film’s antagonists (in contrast with giant arthropods). As well, bees can be controlled chemically—by pheromones—to cluster or land in a particular spot and so are more easily manipulated for special effects. Five films were made about killer bee invasions between 1974 and 1978 (Table I), although none of them was particularly successful at the box office (despite, in the case of the 1978 film The Swarm, a screenplay by renowed science fiction writer Arthur Herzog and a cast with such Academy Award-caliber actors as Henry Fonda and Michael Caine).

In many of the films featuring large numbers of small insects, ecological disruption is a recurring theme. Biomagnification, accumulation of toxins up a food chain, is the focus of Kingdom of the Spiders; tarantulas take over a town and start consuming livestock because “DDT” destroyed the food chain and deprived them of their normal prey. Other films depicting altered food web dynamics as a result of pollution (radioactive and/or toxic waste) include Skeeters and Empire of the Ants. In Ticks, fertilizers and other chemicals used by illegal marijuana growers are encountered by ticks, which grow to enormous size and terrorize a group of inner-city teens in the woods on a wilderness survival trip.

Another ecological phenomenon of concern both in the movies and in real life is the accidental introduction of alien species (although in the movies these are more likely to be real aliens, from outer space, not just a foreign country). Arachnophobia depicts the fictional consequences of the accidental introduction of a South American

Table I |

|||

Live-Action Feature Films with Arthropods as |

Major Components |

||

| Year | Film | Year | Film |

| 1938 | Yellow Jack | 1992 | Candyman |

| 1944 | Sherlock Holmes and the Spider Woman | 1993 | Cronos |

| 1944 | Once upon a Time | 1993 | Matinee |

| 1950 | Highly Dangerous | 1993 | Ticks |

| 1953 | Mesa of Lost Women | 1994 | Centipede Horror |

| 1954 | Them! | 1994 | Skeeters |

| 1954 | The Naked Jungle | 1995 | Mosquito (aka Nightswarm) |

| 1955 | Tarantula | 1996 | Angels and Insects |

| 1957 | The Black Scorpion | 1996 | Wax, or the Discovery of Television among the Bees |

| 1957 | Beginning of the End | 1996 | Joe’s Apartment |

| 1957 | Earth vs the Spider | 1996 | Wasp Womana |

| 1957 | The Deadly Mantis | 1997 | Starship Troopers |

| 1957 | Monster from Green Hell | 1997 | Men in Black |

| 1958 | The Cosmic Monsters | 1997 | Mimic |

| 1958 | She Devil | 1998 | X-Files: The Movie |

| 1958 | The Fly | 1999 | Deadly Invasion: The Killer Bee Nightmarea |

| 1959 | Return of the Fly | 1999 | Atomic Space Bug |

| 1959 | The Brain Eaters | 2000 | They Nesta |

| 1959 | Wasp Woman | 2000 | Bug Blastera |

| 1962 | Mothra | 2000 | Hell Swarma |

| 1964 | Godzilla vs The Thing | 2000 | Spiders (aka Cobwebs) |

| 1965 | Horrors of Spider Island | 2000 | Island of the Dead |

| 1966 | The Deadly Bees | 2001 | Deadly Scavengers |

| 1968 | Destroy All Monsters! | 2001 | Evolution |

| 1969 | The Blood Beast Terror (aka The Vampire Beast Craves Blood) 2001 | Bug | |

| 1970 | Flesh Feast | 2001 | Mimic II: Hardshell |

| 1971 | The Hellstrom Chronicle | 2001 | Spiders II |

| 1971 | The Legend of Spider Forest | 2001 | Tail Sting |

| 1972 | Kiss of the Tarantula (aka Shudders) | 2001 | Bug Off! |

| 1973 | Invasion of the Bee Girls | 2001 | Killer Buzz (aka Flying Virus) |

| 1974 | Phase IV | 2001 | Arachnid |

| 1974 | Locusts” | 2001 | Earth vs. the Spider |

| 1974 | The Killer Beesa | 2002 | Men in Black II |

| 1975 | Bug | 2002 | Spiderman |

| 1975 | The Giant Spider Invasion | 2002 | Eight-Legged Freaks |

| 1975 | Food of the Gods | 2002 | Infested |

| 1976 | The Savage Beesa | 2002 | The Tuxedo |

| 1976 | Curse of the Black Widowa | 2002 | Killer Beesa |

| 1977 | Empire of the Ants | 2003 | Bugsa |

| 1977 | Exorcist II—The Heretic | 2003 | Deadly Swarm |

| 1977 | Ants: It Happened at Lakewood Manor” | 2003 | The Bone Snatcher |

| 1977 | Kingdom of the Spiders | 2003 | Arachnia |

| 1977 | Terror out of the Skya | 2004 | Centipede! |

| 1978 | Tarantulas: The Deadly Cargoa | 2004 | Bite Me! |

| 1978 | The Bees | 2005 | Alien Apocalypsea |

| 1978 | The Swarm | 2005 | Insecticidal |

| 1978 | Curse of the Black Widowa | 2005 | Mansquito (aka Mosquito Man) |

| 1982 | Creepshow | 2005 | Stinger |

| 1982 | Legend of Spider Forest | 2005 | Glass Trap |

| 1985 | Flicks | 2005 | Swarmeda |

| 1985 | Creepers (aka Phenomena) | 2006 | Caved Ina |

| 1986 | The Fly | 2007 | Black Swarm |

| 1987 | Blue Monkey | 2007 | Destination: Infestationa |

| 1987 | The Nest | 2007 | In the Spider’s Web” |

| 1987 | Deep Space | 2007 | Ice Spidersa |

| 1989 | The Fly II | 2007 | The Mist |

| 1990 | Arachnophobia | 2008 | Starship Troopers 3: Marauder |

| 1991 | Meet the Applegates | 2008 | The Hivea |

| 1991 | The Age of Insects | 2009 | The Unborn |

| 1991 | The Willies | ||

spider species to the Pacific Northwest. The many killer bee movies pointedly make reference to the dangers of accidental importation of strains of bees into new habitats (although in The Bees their introduction is no accident; greedy cosmetics magnates import killer bees in the hope of producing large amounts of profitable royal jelly).

INSECTS IN DOCUMENTARY FILMS

Although educational shorts for school and extension markets often deal with entomological topics, documentary filmmaking, which combines information and art, has tended to skirt insect subjects. For a long time, documentary filmmakers faced many of the same challenges faced by feature filmmakers with an interest in insects. Only in the latter half of the 20th century did developments in technology permit the capture of small moving objects (such as insects) on film in a compelling and effective manner. Yet another obstacle, particularly problematic for documentary filmmakers, was audience interest; whereas audiences could accept insects bent on destruction of the human race in science fiction or horror films, they generally showed considerably less interest in the accurate depiction of the lives of real-life insects. Animal documentary filmmakers have long had to accept the fact that audiences prefer drama to accuracy in depictions of nature. Walt Disney, with his groundbreaking True Life Adventure nature films made between 1948 and 1970, relied in many of his nature films on personification and anthropomorphism to make the animal subjects of studio films more appealing to audiences.

Arguably the first “documentary” films involving insects were the pioneering efforts of F. Percy Smith, who in 1912 created films aimed at illustrating the physical prowess of the common house fly. Smith enclosed a fly inside a dark box equipped with a thin glass door at one end; the door in turn had a small opening into which was fitted a toothed wheel that was free to rotate. The fly, orienting to the light entering through the glass door at one end of the box, would move toward the light; when it encountered the glass door obstructing its escape, it was struck on the head by a tooth in the wheel which rotated as a consequence of the fly’s movements. Eventually, via conditioning, the fly simply walked up the wheel, which would rotate, creating a treadmill and providing the photographer an opportunity to film the fly walking in place. Smith modified his approach to film flies outside the box, tethered in place, and in this way was able to obtain footage of them seemingly juggling dumbbells, corks, bits of vegetables, other flies, and sundry other objects. When the film was released, newspaper reports accredited the cinematographer with the ability to train house flies as others do circus animals.

Audience reluctance to accept insects for their own sake is the explanation for the peculiar framing device used in the first big-budget feature-length documentary about insects, The Hellstrom Chronicle , This film was originally conceived as a straightforward documentary and featured what was at the time state-of-the-art mac-rophotography that provided startling and dramatic close-ups of its arthropod subjects. The extraordinary inventiveness of cinematogra-pher Ken Middleham led to spectacular images of insects engaged in a wide range of behaviors. However, the studio heads were unconvinced that a documentary about insects could bring in an audience and insisted on adding to the film a fictional storyline, about an academic, Dr. Nils Hellstrom (Lawrence Pressman), denied tenure because of his insistence that insects were bent on human destruction. As a result, the hybrid film was a commercial success as well as an artistic success of sorts (earning a Grand Prix de Technique award at the 1971 Cannes Film Festival for its remarkable images), although it was panned by critics, in part because of its sensational-istic tone.

A general awakening of the American public to environmental issues in the 1970s did little to inspire interest in insect biology, and insect documentaries have been few and far between since The Hellstrom Chronicle. Insects figured peripherally in the documentary Cane Toads, An Unnatural History, directed and written by Mark Lewis, and first shown in 1988. The cane toad Bufo marinus was deliberately introduced into North Queensland, Australia in 1935 to control Lepidoderma albohirtum (a beetle larva) and its relatives. Although the cane toads were ineffectual biocontrol agents, they were exceptionally effective colonizers and they now populate much of Queensland, northern New South Wales, and eastern Northern Territory, wreaking ecological and environmental havoc. The history of this ill-conceived biocontrol effort and its consequences are the subject of the documentary.

Microcosmos (1996) is similar to The Hellstrom Chronicle in that its success was due largely to quantum improvements in capturing insect images and behavior on film. Filmmakers Claude Nuridsany and Marie Perennou spent 15 years researching, 2 years designing equipment (including inventing a remote-controlled helicopter for aerial shots), 3 years shooting, and 6 months editing a masterpiece of insect cinematography. Yet the concept underlying the film was quite novel. Instead of a “superdocumentary” of amazing insect feats, the filmmakers settled on the idea of telling the story of a single summer day (albeit in reality filmed over a much longer period of time) in a field in the countryside of Aveyron, France (where they lived and worked). Their goal was to depict insects and other small creatures not as ” small bloodthirsty robots ” but rather as individuals with unique abilities. Instead of narration, there was a simple introduction, 40 words, spoken by actress Kristin Scott Thomas. Microcosmos was well received by critics (although it failed to win a nomination for best documentary at the Academy Awards), and it performed respectably at the box office. Although some notable entomologists bemoaned the absence of voiceover and the loss of an opportunity to educate the public about the insect lives captured on film, the extraordinary images depicted on screen will likely set the standard for excellence in insect documentary filmmaking for years to come.

INSECT WRANGLERS AND SPECIAL EFFECTS

Because handling insects and other arthropods and eliciting appropriate behaviors from them on cue is beyond the experience and training of most directors, these responsibilities are frequently delegated to a specialized crew member known in the profession as an “)nsect wrangler” or “bug wrangler.” Since the early 1960s, only a handful of individuals have engaged in this occupation in a conspicuous way. Some insect wranglers specialize in handling a narrow range of taxa. Norman Gary has been a bee wrangler for more than a quarter-century. Currently an emeritus professor at University of California at Davis, he served as a faculty member in bee biology from 1962 to 1994. His research interests have been in the area of bee behavior, and he has written or coauthored over 100 publications on bees. Since 1966, he has been a consultant for legal, industrial, film, and television productions about bees. His ingenuity in developing methods for manipulating bees and their behavior has led him to develop methods of narcotizing queens to facilitate instrumental insemination, as well as vacuum devices for tagging, counting, confining, and otherwise handling bees. An abbreviated filmography for Gary includes My Girl, Fried Green Tomatoes, Candyman, Beverly Hillbillies, Man of the House, X-Files, The Truth about Cats and Dogs, Leonard Part VI, A Walk in the Clouds, and Invasion of the Bee Girls.

Another individual with an affinity for a particular taxon is Ray Mendez, who worked as an entomologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Mendez, along with colleague David Brody, provided over 20,000 cockroaches for the film Creepshow in 1982; in 1996 Mendez wrangled 5000 live cockroaches and provided advice on animated and puppet cockroaches for the film Joe’s Apartment. Mendez is also an authority on naked mole rats and was featured in the documentary Fast, Cheap and Out of Control.

Steven R. Kutcher, a consulting entomologist in Arcadia, California, and part-time biology instructor at West Los Angeles College, is notable for the range of arthropods with which he has worked. Kutcher obtained a bachelor’s degree in entomology at University of California at Davis and a master’s degree in biology with an emphasis on insect behavior and ecology at California State University, Long Beach. Since 1976 he has been involved in arthropod wrangling for many movies and commercials. He has worked with a variety of arthropods, including spiders, yellowjackets, cockroaches, mealworms, grasshoppers, and several species of butterflies. Among his film credits are Extremities, Exorcist II: The Heretic, Arachnophobia, Race the Sun, Jurassic Park, and Spiderman. His unusual vocation has made him the focus of more than 100 print articles, and in 1990 his work was the subject of a short documentary by National Geographic.

INSECT FEAR FILM FESTIVALS

The idea of using insects in movies as a means of entomological outreach apparently dates back to the origins of the annual Insect Fear Film Festival at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The first festival, brainchild of then assistant professor of entomology May Berenbaum, was held in March 1984. The goal of the festival has been to recruit audiences with insect fear films and then use the films as a means for highlighting popular misconceptions about insects. At each festival, two or three feature-length films are shown, interspersed with animated shorts. Before the festival begins, and between films, the audience is invited to see and handle a variety of live as well as pinned specimens. Generally, the festivals are organized around themes, which have included, among others, noninsect arthropods, orthopterans, social insects, cockroaches, flies, alien arthropods, and mosquitoes. The 20th festival featured three films by Bert I. Gordon and the 25th festival featured films of Simon Smith; both directors actually attended the festivals.

Other events that have been held in conjunction with the festival included a thematically relevant blood drive, held in cooperation with Community Blood Services of Champaign, for the 1999 mosquito film festival. Attendance at these festivals can exceed 1000. Over the years, the festival has been featured in a wide range of media throughout the world.

Other insect fear film festivals per se are few in number; Iowa State University has conducted an Insect Horror Film Festival since 1985, and Washington State University has hosted its Insect Cinema Cult Classics festival since 1990. Insect films, however, have been elements of insect expo and public outreach efforts in many venues, including museums, science centers, and universities across the country.

There is one legitimate insect film festival in the traditional sense, in which films are submitted in competition and are judged and awarded prizes. FIFI, organized by l’Office pour les Insectes et leur Environnement du Languedoc-Roussillon (OPIE LR) and the the Regional Natural Park of Narbonne and the city of Narbonne, France, is a biennial international film festival dedicated to insects and other small animals. The FIFI, in its seventh session in 2007, is the result of a partnership with the Institute for Research and Development, the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), the National Institute of Agronomic Research (INRA), the City of Sciences and Industry and the National Museum of Natural History (Paris), and the Agronomic University of Gembloux (Belgium). Its stated objectives are to increase the sensitivity of the media and the public to the ecological importance of continental invertebrates and to encourage and promote the making of films or videos dedicated to insects.

FUTURE OF INSECTS IN CINEMA

With the continuing development of computer-generated imaging (CGI) and the explosion of such outlets for films as cable stations, satellite television, DVD and video markets, the future of insects and other arthropods in the movies looks secured. Arthropods will certainly continue to be objects of distaste and unease for audiences throughout the world and so will remain staples of horror films and sci-fi adventures. Moreover, CGI and developments in macrophotography ensure that insect images on screen will become increasingly sophisticated, although scriptwriting will doubtless remain as resolutely unrealistic as it has since the earliest days of insects in cinema.