Specialized Terms fat body A structure within the cockroach body that contains stored nutrients, uric acid, and endosymbiotic bacteria, each housed in a different cell type.

formulation The form in which an insecticide is applied: the most common formulations are sprays, dusts and baits.

mode of action The mechanism by which an insecticide affects an insect.

mycetocyte The cockroach fat body cell type that houses endosymbiotic bacteria

ootheca The structure into which cockroaches deposit their eggs: also called an egg case.

pronotum The shield-like plate covering the dorsum of the first thoracic segment in cockroaches.

Cockroaches are an ancient and highly successful form of insect life. They were among those groups of insects that evolved during the first great radiation of insects, and primitive or ancestral cockroaches have been in existence for about 350 millions years or since early Carboniferous times. They appear to have achieved an optimum body form and other features early in their evolutionary history. Fossil specimens are relatively abundant and some that are about 250 million years old are easily recognizable as cockroaches and could pass for modern species. Among the features that allowed them to escape the extinction that claimed many earlier insect groups was the ability to fold their wings over the body. This allowed them to more easily hide from predators and escape other dangers. They also evolved early in their existence an ootheca that offered some measure of protection for their eggs because it could be hidden or carried by the female.

Cockroaches are referred to as generalized orthopteroid insects which classifies them with the true Orthoptera (crickets, katydids, grasshoppers, locusts), Phasmatodea (walking sticks), Mantodea (praying mantids), Plecoptera (stoneflies), Dermaptera (earwigs), Isoptera (termites), and a few other minor groups. The phylogenetic relationships among all of these groups are not firmly established, although several theories exist. The closest relatives of cockroaches are believed to be the mantids, and some modern taxonomists prefer to place these two groups, as well as termites, in the Order Dictyoptera. Indications are that termites evolved out of the cockroach stem or that cockroaches

and termites both evolved from a common ancestor. One family of cockroaches (Cryptocercidae) and one extant relic species of termite (Mastotermes darwiniensis) have certain characteristics in common. Among them are the segmental origin of specific structures in the female reproductive system and that both deposit their eggs in similar blattarian-type oothecae. They also share a system of fat body endo-symbiotic bacteria that is unique to Mastotermes among the termites, but is common to all cockroaches studied with the exception of the genus Nicticola.

THE SPECIES OF COCKROACHES

Between 3500 and 4000 species of cockroaches have been identified, with one relatively simple classification scheme dividing this group into five families as follows:

• Cryptocercidae It is the most primitive family and consists of one genus with fewer than 10 species. They live as isolated family groups in decaying logs and occur in the United States, Korea, China, and Russia. They are large, reddish brown insects that are wingless as adults.

• Blattidae It is a diverse family with many genera and hundreds of species. Those classified as Periplaneta and Blatta are widely distributed, whereas other genera are more regional. They are large insects that tend to live outdoors. Several species are referred to locally as palmetto bugs.

• Blattellidae It is also a diverse family with many genera and around 1000 species. They are widely distributed in the world but are concentrated in the tropics and subtropics. Blattellids are mostly small outdoor cockroaches, including those called wood cockroaches. The genus Blattella contains the German cockroach.

• Blaberidae It is the largest family of cockroaches with dozens of genera and more than 2000 species. They are widely distributed outdoors in tropical and subtropical regions. Some members of the genus Blaberus are extremely large, reaching more than 80 mm in length. These are the most highly evolved cockroaches having developed the ability to incubate, and in some cases nourish, their eggs internally.

• Polyphagidae It is a small family with only a few described genera and 100-200 species. Females of most species are wingless. They are widely distributed in harsh environments, such as deserts and other arid climates. Some members of the genus Arenivaga have evolved structures that can absorb moisture from humid air.

Other, more complex, classification schemes for cockroaches also exist, indicating that the subject is not entirely settled. The finding that the genus Nicticola does not contain endosymbiotic bacteria, attested to by the failure to amplify the expected bacterial 16S rRNA and confirmed microscopically by the absence of fat body myceto-cytes, indicates that the Nicticolidae should be raised to family status, as it already is in some schemes. In addition, insect collections from previously unexplored locations often include many unde-scribed cockroach species. Thus, it is likely that the total number of extant species is much higher than the figures given above. Contributing to this uncertainty is the fact that the vast majority of cockroaches live in the tropical regions of the world and many of these regions have not been adequately assessed to establish the diversity of insect life, including cockroaches, occurring there.

Cockroaches, being hemimetabolous insects, have egg, nymph, and adult stages and grow through a series of molts. They vary greatly in size, ranging from a few millimeters to over 100 mm in length. Many cockroaches are dark brown, but some are black or tan and others show a surprising amount of color variation and cuticular color patterns. Most species have four wings as adults and some are capable of rapid, sustained flight; others are wingless or have wings that are variously reduced in size. The majority of species are either nocturnal (or are hidden from view because of where they live), but some are diurnal. Cockroaches occupy diverse habitats, such as among or under dead or decaying leaves, under stones or rubbish, under the bark of trees, under drift materials near beaches, on flowers, leaves, grass, or brush, in the canopy of tall trees, in caves or burrows, in the nests of ants, wasps, or termites, in semiaquatic environments, and in burrows in wood. Thus, the common view of cockroaches as pests is not representative of the group as a whole.

COCKROACHES AS PESTS

There are several reasons why some cockroaches are considered to be pests but the most important one is based on those species that invade people’s homes and other buildings and become very numerous. Most people find this to be objectionable, in part because the important pest species also have an unpleasant odor and soil foods, fabrics, and surfaces over which they crawl. However, on a worldwide basis less than 1% of all known cockroach species interact with humans sufficiently to be considered pests. The actual number varies depending on location because some pest species are greatly restricted in their global distribution. It is also true that more pest species are encountered in tropical locations than in the colder parts of the world. Of the 25-30 species that can be a problem, more than half are only occasionally of importance and should be considered as minor or even incidental pests. Of the remaining species, only 4 or 5 are of global importance as pests, with the other 9 or 10 species being of regional significance.

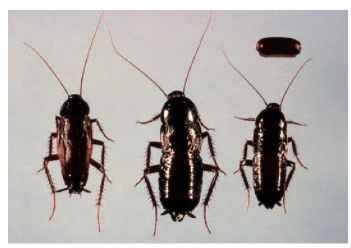

The most important pest species is the German cockroach, Blattella germanica (Blattellidae) (Fig. 1). It has a worldwide distribution and can survive well in association with any human habitation that provides warmth, moisture, and food. It is small, measuring 10-15 mm in length. Adults are yellowish-tan but nymphs are black with a light-colored stripe up the mid-dorsum. There are two longitudinal, black, parallel bands on the pronotum of both nymphs and adults. The wings cover most of the body in adults of both sexes. This is a nocturnal species that lives mainly in kitchen and bathroom areas. When a person enters the kitchen of an infested house at night

FIGURE 1 The German cockroach, Blattella germanica. From left: adult male, adult female, nymph, ootheca.

and turns on a light, the cockroaches scurry out of sight— a startling experience that adds to the desire to eliminate them. There are three or four generations per year. Each egg case (ootheca) contains 25- 50 eggs, and each female can produce 3-6 oothecae. The potential for rapid population expansion is obvious.

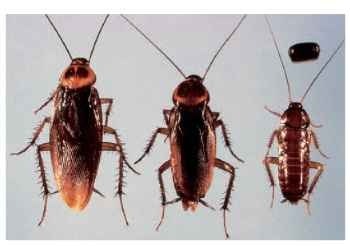

The oriental cockroach, Blatta orientalis (Blattidae) (Fig. 2), is the next most important pest species, but is restricted to the more temperate regions of the world. It is large, measuring 20-27 mm in length. All stages are dark brown to black in color. Females are essentially wingless, whereas in males the wings cover about two-thirds of the abdomen. This cockroach frequents basements and crawls spaces under buildings, where temperatures are cooler, and often lives outdoors. It is a long-lived insect and may require 1-2 years to complete its life cycle. The ootheca contains 16 eggs, and one female may produce 8 or more oothecae. Under favorable conditions it can become very numerous.

FIGURE 2 The oriental cockroach, Blatta orientalis. From left: adult male, adult female, nymph, ootheca.

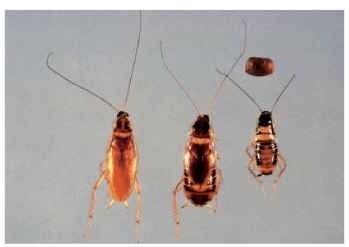

There are five or six species belonging to the genus Periplaneta (Blattidae) (Fig. 3) that are important pests. The American cockroach, P. americana, is the most notorious. It measures 35-40 mm in length and is a chocolate-brown color in all stages. Adults of both sexes are fully winged and may undertake a weak flight. It is widely distributed around the world, but does not extend into the temperate zones as far as does the German cockroach. It requires 6-9 months to complete its life cycle. Among other Periplaneta species of importance are the Australian cockroach, P. australasiae, the smoky-brown cockroach, P. fuliginosa, and the Japanese cockroach, P. japonica. They each have a more restricted distribution. The latter species, for example, is found in Japan and China. They are all large cockroaches with a long life cycle, but can become numerous under certain conditions. They tend to be outdoor cockroaches, but often occupy buildings in which food is stored, prepared, or served.

The brown-banded cockroach, Supella longipalpa (Blattellidae) ( Fig. 4 ), is a nearly cosmopolitan pest. It is small, measuring 10 – 14 mm in length. As its common name indicates, there are two dark, transverse stripes or bands on the dorsum. The pronotum lacks the two black bands found on the German cockroach. Nymphs are light colored. Females produce numerous oothecae and glue them in inconspicuous places. Each one has about 16 eggs. The life cycle requires approximately 3 months to complete. This cockroach occupies homes and

FIGURE 3 The American cockroach, Periplaneta americana. From left: adult male, adult female, nymph, ootheca.

FIGURE 4 The brown-banded cockroach, Supella longipalpa. From left: adult male, adult female, nymph, ootheca.

other buildings but is not restricted to the kitchen and bathroom, as is the German cockroach.

Other pest species include the Turkistan cockroach, Blatta lateralis (Blattidae), two species in the genus Polyphaga (Polyphagidae), the Madeira cockroach, Rhyparobia maderae (Blaberidae), the lobster cockroach, Nauphoeta cinerea (Blaberidae), the Suriname cockroach, Pycnoscelus surinamensis (Blaberidae), the Asian cockroach, Blattella asahinai (Blattellidae), the harlequin cockroach, Neostylopyga rhombifolia (Blattidae), and the Florida cockroach, Eurycotisfloridana (Blattidae). Most of these species are of regional concern as pests.

COCKROACHES AND HUMAN HEALTH

Cockroaches harbor many species of pathogenic bacteria and other types of harmful organisms on or inside their bodies, but they do not transmit human diseases in the same manner as do mosquitoes. They acquire these organisms because of their habit of feeding on almost any type of organic matter, including human and animal wastes. These cockroach-borne organisms can remain viable for a considerable period of time. If the cockroach next visits and soils food intended for human consumption, it is likely that some of the harmful organisms will be deposited on the food. Consuming such food can lead to gastroenteritis, diarrhea, and other types of intestinal infections and pathogenic conditions.

Cockroaches have been shown to harbor pathogenic bacteria belonging to the genera Mycobacterium, Shigella, Staphylococcus, Salmonella, Escherichia, Streptococcus, and Clostridium. They also harbor pathogenic protozoa in the genera Balantidium, Entamoeba, Giardia, and Toxoplasma. and parasites in the genera Schistosoma, Taenia, Ascaris, Ancylostoma, and Necator. From these lists of organisms it is clear that cockroaches are important as potential disease vectors.

Cockroaches are also important because people can become allergic to them, especially given constant exposure. These reactions usually involve the skin and/or respiratory system. Studies have shown that people who exhibit skin or bronchial responses to cockroaches have elevated levels of cockroach-specific antibodies. These responses can be severe and may require treatment. The species most commonly involved in producing allergic reactions are the German and American cockroaches.

COCKROACH CONTROL

There are several considerations that come into play in any discussion of cockroach control. The first is an understanding of how infestations arise. The usual modes of entry for German and brown-banded cockroaches are through infested parcels containing food or other materials, and by movement from abutting dwellings. Most of the other, larger pest species tend to live outdoors and can migrate from one building to another. They can also be introduced in parcels. Thus, the next consideration is prevention of entry. All entering parcels should be inspected to be sure they do not contain cockroaches, and dwelling defects should be corrected to exclude invaders. Finally, human living space should be kept free of clutter, which can act as hiding places for cockroaches, and food left on dishes, in sinks, or on floors, which can feed a population of cockroaches, should be disposed of properly.

When infestations occur, there are two main methods of control. The first is non-chemical. It includes trapping and vacuuming cockroaches, both of which can significantly reduce the size of an infestation. In addition, freezing, overheating, or flooding structures with a non-toxic gas can be used to kill the pests. Some of these latter procedures require specialized equipment and are best done by professional pest-control operators.

The most common method of control is the use of chemical poisons. Many kinds of insecticides can be used to kill cockroaches. They may be applied as aerosols, baits, dusts, granulars, as crack and crevice treatments, or in traps. Some are contact poisons that are absorbed as cockroaches walk over treated surfaces. The most common of these belong to the chemical classes called pyrethroids, organophosphates, and carbamates. They kill by disrupting the insect’s nervous system, each in a specific manner. Those administered in bait formulations must be eaten by the cockroach. Among them are dinotefuran, aver-mectin and fipronil, which attack the nervous system, hydramethyl-non, which disrupts cellular respiration, and boric acid, which destroys the cells lining the insect gut wall. The insect growth regulator hydro-prene is used in some formulations. Each of these materials, as well as others not mentioned, has its own chemical characteristics and must be used in accordance with label instructions.

New insecticides are regularly being introduced, and older ones are being phased out. A critical goal is to develop safer chemicals and safer methods of applying them. For example, the older practice of applying insecticides to surfaces over which cockroaches are expected to crawl is being used less frequently and, as a consequence, especially the organophosphate and carbamate insecticides are being phased out. The practice of dispensing chemicals as baits has largely replaced the surface-application method. With baits the insecticide is more confined and its safety is thereby enhanced. The use of baits has become practical in recent years because some of the newer chemicals are highly palatable for cockroaches in bait formulations.

Cockroach control in the future will likely depend on the availability of new insecticides as well as the development of better methods of applying them. Among the approaches that are possible is searching for chemicals that act on sites not previously exploited. For example, a combination of two chemicals is known that prevents cockroaches from producing uric acid. Previous research has shown that storing and recycling the chemical constituents in uric acid is critical to the survival of cockroaches. The functioning of this system is dependent on the fat body endosymbiotic bacteria mentioned above. Other points of metabolic vulnerability will also probably be found in the future.

Another reason why new chemical approaches are needed is that the most important cockroach pest, Blattella germanica, has become resistant to many of the older insecticides. When this occurs, the effectiveness of those chemicals is either greatly reduced or they become useless against resistant populations. With continued use of the newer chemicals, resistance to some of them will probably occur. A steady supply of new chemicals with new modes of action will greatly alleviate this problem and facilitate continued control.