Aedes Mosquito

Aestivation

Aestivation is a dormant state for insects to pass the summer in either quiescence or diapause. Aestivating, quiescent insects may be in cryptobiosis and highly tolerant to heat and drought. Diapause for aestivation, or summer diapause, serves not only to enable the insect to tolerate the rigors of summer but also to ensure that the active phase of the life cycle occurs during the favorable time of the year.

QUIESCENCE

Quiescence for aestivation may be found in arid regions. For example, the larvae of the African chironomid midge, Polypedilum vanderplanki, inhabit temporary pools in hollows of rocks and become quiescent when the water evaporates. Dry larvae of this midge can “revive” when immersed in water, even after years of quiescence. The quiescent larva is in a state of cryptobiosis and tolerates the reduction of water content in its body to only 4%, surviving even brief exposure to temperatures ranging from +102°C to -270°C. Moreover, quiescent eggs of the brown locust, Locustana pardalina, survive in the dry soil of South Africa for several years until their water content decreases to 40%. When there is adequate rain, they absorb water, synchronously resume development, and hatch, resulting in an outburst of hopper populations. The above-mentioned examples are dramatic, but available data are so scanty that it is difficult to surmise how many species of insects can aestivate in a state of quiescence in arid tropical regions.

SUMMER DIAPAUSE

Syndrome

The external conditions that insects must tolerate differ sharply in summer and winter. Aestivating and hibernating insects may show similar diapause syndromes: cessation of growth and development, reduction of metabolic rate, accumulation of nutrients, and increased protection by body coverings (hard integument, waxy material, cocoons, etc.), which permit them to endure the long period of dormancy that probably is being mediated by the neuroendocrine system.

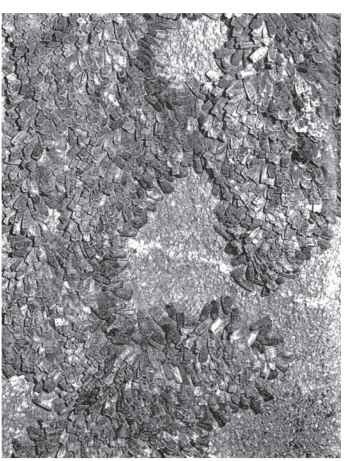

Migration to aestivation sites is another component of diapause syndrome found in some species of moths, butterflies, beetles, and hemipterans. In southeastern Australia, the adults of the Bogong moth, Agrotis infusa, emerge in late spring to migrate from the plains to the mountains, where they aestivate, forming huge aggregations in rock crevices and caves (Fig. 1 ).

Seasonal Cues

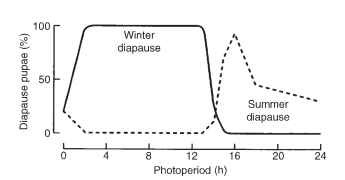

Summer diapause may be induced obligatorily or facultatively by such seasonal cues as daylength (nightlength) and temperature. When it occurs facultatively, the response to the cues is analogous to that for winter diapause; that is, the cues are received during the sensitive stage, which precedes the responsive (diapause) stage. The response pattern is, however, almost a mirror image of that for winter diapause (Fig. 2) . Aestivating insects themselves also may be sensitive to the seasonal cues; a high temperature and a long daylength (short nightlength) decelerate, and a short daylength (long nightlength) and a low temperature accelerate the termination of diapause.

The optimal range of temperature for physiogenesis during summer diapause broadly overlaps with that for morphogenesis, or extends even to a higher range of temperature. Aestivating eggs of the brown locust, L. pardalina, can terminate diapause at 35°C and those of the earth mite, Halotydeus destructor, do this even at 70°C. The different thermal requirements for physiogenesis clearly distinguish summer diapause from winter diapause, suggesting that despite

FIGURE 1 Bogong moths, Agrotis infusa, aestivating in aggregation on the roof of a cave at Mt Gingera, A. C. T., Australia. [Photograph from Common, I. (1954).

FIGURE 2 Photoperiodic response in the noctuid M. brassicae controlling the pupal diapause at 20°C. Note the different ranges of photoperiod for the induction of summer diapause (dashed line) and winter diapause (solid line).

the superficial similarity in their dormancy syndromes, the two types of diapause involve basically different physiological processes.