INTRODUCTION

Information technology (IT) governance has been a perennial item on the corporate agenda of many organizations. Ever since IT proved to be more than an administrative tool, researchers and practitioners have pondered its governance. Defined as the locus of IT decision-making authority (Brown & Magill, 1994; Sambamurthy & Zmud, 1999), discussions concerning IT governance have flourished for more than four decades across research communities and boardrooms. Posed as a question of centralization during the 70s, IT governance drifted towards decentralization in the 80s, and the recentralization of IT decision-making was a 90s trend.

Today, IT governance is experiencing yet another transformation, and persists as a complex and evolving phenomenon (Grembergen, 2003). As business environments continuously change and new technologies evolve rapidly, how to govern IT effectively remains an enduring and challenging question. This chapter discusses past developments and the present status quo of IT governance, and outlines several critical questions, which are pending future investigation.

BACKGROUND

Traditionally, three IT governance models have been distinguished (Brown & Magill, 1998; Sambamurthy & Zmud, 1999). In each model, stakeholder constituencies take different lead roles and responsibilities for IT decision-making across the IT portfolio. In the centralized model, corporate IT management has decision-making authority concerning IT infrastructure and IT applications. In the decentralized model, division IT management and business management have authority for IT infrastructure and IT applications. In the federal model, corporate IT has authority over IT infrastructure, and (either or both) division IT and business-units have authority over IT applications.

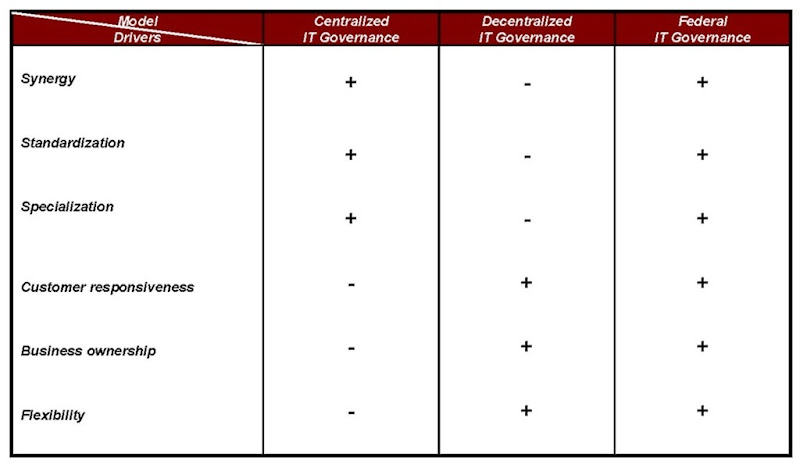

In general, it is argued that centralization provides greater efficiency, control, and standardization, while decentralization improves business ownership, flexibility, and responsiveness (Brown, 1997; Rockart, Earl, & Ross, 1996). Literature suggests that the federal model provides the benefits of both centralization and decentralization (see Table 1). Research indicates that organizations adopt a federal model when pursuing multiple competing objectives involving a simultaneous focus on cost-efficiency and business-flexibility (Peterson, O’Callaghan, & Ribbers, 2000; Sambamurthy & Zmud,1999).

Table 1. Drivers and design of IT governance

MAIN THRUST

While the federal model seems to be the dominant configuration in contemporary firms (Peterson, O’Callaghan, & Ribbers, 2000; Sambamurthy & Zmud, 1999), empirical studies regarding the complexity of this configuration are sparse. Specifically, allocation of IT decision-making authority does not resolve the need for effective coordination between corporate IT, division IT and business-unit management. Continuous differentiation leads to fragmentation, unless a corresponding process of integration complements it. The problems reported in practice and research regarding the lack of, for example, IT prioritization, top management IT commitment, IT management business understanding, business management IT responsibility, and IT value generation, are symptomatic of this fragmentation and are typically encountered in the federal IT governance model (Peterson, 2001; Weill & Broadbent, 1998).

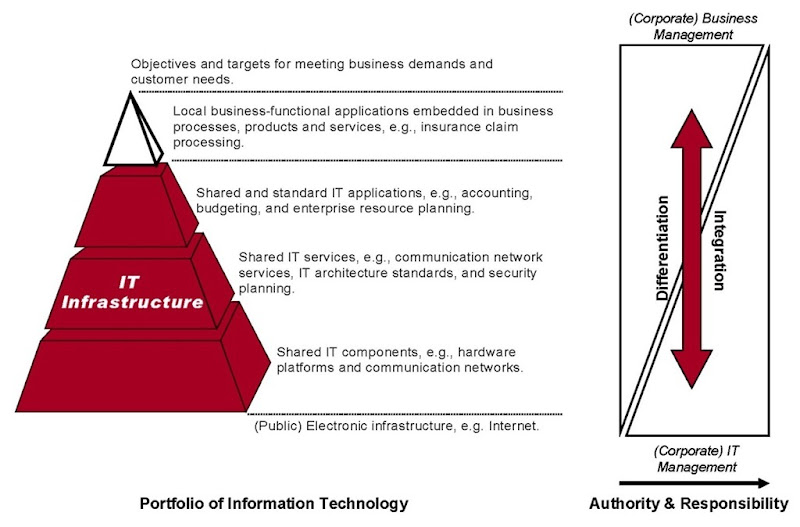

In order to provide direction and achieve organizational effectiveness, differentiation begets integration (Daft, 1998; Galbraith, 1994; Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967). Designing effective IT governance is dependent on both the differentiation and integration of decision-making for IT across the portfolio of business IT investments and processes (see Figure 1).

Whereas differentiation focuses on the distribution of IT decision-making rights and responsibilities among different stakeholders in the organization (i.e., the locus of IT decision-making), integration focuses on the coordination of IT decision-making/-monitoring processes and structures across stakeholder constituencies. Organizations thus need to consider and implement integration mechanisms for the effective governance of IT.

FUTURE TRENDS

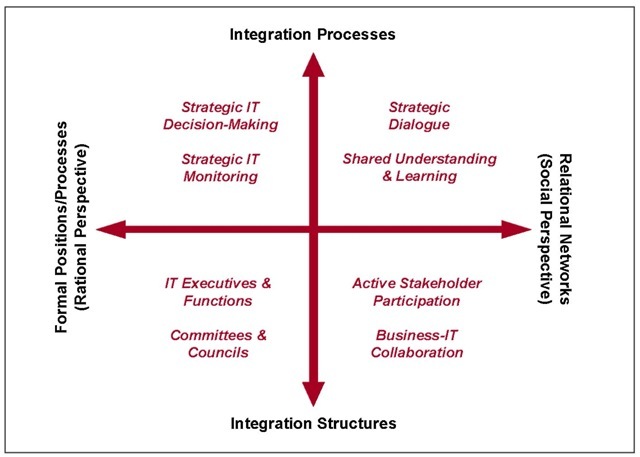

Integration mechanisms for IT governance can be classified according to two dimensions (Peterson, 2003). Vertically, integration mechanisms focus either on integration structures or integration processes; whereas horizontally, a division is made between formal positions and processes, and relational networks and capabilities. Collectively, this provides four types of generic integration mechanisms for IT governance (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Differentiation and integration IT decision-making

Figure 2. Generic integration mechanisms for IT governance

Formal integration structures involve appointing IT executives (e.g., CIO) and IT functions (e.g., client-account and user relationship managers), and institutionalizing special and standing IT committees and councils. Committees and/or executive teams can take the form of temporary task forces (e.g., project steering committees), or can alternatively be institutionalized as an overlay structure in the organization in the form executive and/or IT management councils. Formal integration processes describe the formalization and institutionalization of IT decision-making-/monitoring procedures and performance. Formal integration processes vary with levels of IT governance comprehensiveness, formalization, and integration.

Whereas the foregoing formal integration mechanisms tend to be mandatory and tangible, relational integration mechanisms are “voluntary” and “tacit” actions, which cannot be programmed and/or formalized. While formal integration mechanisms are necessary, they are insufficient for designing effective IT governance in competitive environments (Peterson, O’Callaghan, & Ribbers,2000).

Relational integration structures involve the active participation and collaboration between corporate executives, IT management, and business management. Central to relational integration is the participative behavior of different stakeholders to clarify differences and solve problems in order to find integrative solutions. The ability to integrate relationally allows an organization to find broader solutions, and unleashes the creativity involved in joint exploration of solutions that transcend functional boundaries and define future possibilities. Relational integration processes describe strategic dialogue and shared learning between principle business and IT stakeholders. Strategic IT dialogue incorporates a wide range of initially unstructured business perspectives and IT views, and involves rich conversation to resolve diverging perspectives and stakeholder conflicts. Shared learning describes the co-creation of mutual understanding by members of organizational sub-units of each other’s goals and objectives.

In summation, formal and relational structures and processes collectively constitute and determine the integration capability of IT governance, and underscore the importance of flexible management systems in complex and uncertain environments. The organizing logic is characterized by a collaborative network, where communication is more likely to be lateral, task definitions are more fluid and flexible (i.e., related to competencies and skills, rather than being a function of position in the organization), and where influencing of business-IT decisions is based on expertise, rather than an individual’s (or group’s) position (Peterson, 2003).

Table 2. Future research

| Suggested Research Design and | |||

| Methodology | |||

| What types of integration mechanisms are used in conjunction with different IT governance models? Do certain IT governance gestalts exist that combine IT governance differentiation and integration mechanisms? What are the most effective integration mechanisms under different IT governance models? How do integration mechanisms moderate the relationship between IT governance and IT business value? How do organizations design and implement integration mechanisms for IT governance? What are the (inter-) dependencies between integration mechanisms? Do companies follow a specific path when developing and implementing integration mechanisms (e.g., do they start with positions, the processes and finally relationships?) Are certain drivers (e.g., standardization, responsiveness, flexibility) related to the use (or non-use) of specific integration mechanisms? How do the competing drivers of efficiency and flexibility impact the adoption and usage of integration mechanisms? |

A quantitative approach (large scale survey) to identify and validate patterns of IT governance differentiation and integration. Multiple case studies can also be used to explore and discover new patterns. A quantitative approach (large scale survey) to identify effective integration mechanisms for IT governance. Multiple case studies can be of value when considering the business and industry context. A quantitative approach (large scale survey) to measure and validate the moderating impact of integration mechanisms on IT business value realization A longitudinal research design involving field-research and multiple case studies. A single in-depth case study can also provide rich (theoretical) insights. A longitudinal or retrospective field-study on the development and evolution of integration mechanisms in certain companies Both surveys and/or case studies can be used. A (quantitative) survey would identify empirically significant relationships amongst certain drivers and integration mechanisms. Multiple case studies would help explain why and how these (competing) drivers lead to the adoption and usage of integration mechanisms |

||

CONCLUSION

Amidst the challenges and changes of the 21st century, involving hyper-competitive market spaces, electronically-enabled global network businesses, and corporate governance reform, IT governance has become a fundamental business imperative. IT governance is a top management priority, and rightfully so, because it is the single most important determinant of IT value realization (Mata, Fuerst, & Barney, 1995; Peterson, 2001; Rockart, Earl, & Ross, 1996; Sambamurthy & Zmud, 1999; Weill & Broadbent, 1998).

More than simply assigning and allocating IT decision-making authority, IT governance is the system by which an organization’s IT portfolio is directed, and describes the distribution of IT decision-making rights and responsibilities among different stakeholders in the organization, and the rules and procedures for making and monitoring decisions on strategic IT concerns. These rules and procedures address the integration mechanisms, which are fundamental to effective IT governance.

Nevertheless, research has only recently focused on the use and effectiveness of integration mechanisms for IT governance. More research is definitely and urgently required in this area (Table 2). It is only through empirical investigation of these and other related research questions that we will be able to advance the current body of knowledge and understanding in the area of IT governance.

KEY TERMS

Centralized Model: The concentration of decision-making in a single point in the organization, in which a single decision applies.

Collaboration: A close, functionally interdependent relationship, in which organizational units strive to create mutually beneficial outcomes. Collaboration involves mutual trust, the sharing of information and knowledge at multiple levels, and includes a process of sharing benefits and risks. Effective collaboration cannot be mandated.

Decentralized Model: The dispersion of decision-making, in which different independent decisions are made simultaneously.

Differentiation: The state of segmentation or division of an organizational system into subsystems, each of which tends to develop particular attributes in relation to the requirements posed by the relevant environment. This includes both the formal division, as well as, behavioral attributes of the members of organizational subsystems.

Federal Model: A hybrid configuration of centralization and decentralization, in which decision-making is differentiated across divisional and corporate units.

Integration: 1) The process of achieving unity of effort among various subsystems in the accomplishment of the organizational task (process focus). 2) The quality of the state of collaboration that exists among departments, which is required to achieve unity of effort by the demands of the environment (outcome focus).

IT Applications: Local business-functional applications embedded in business processes, activities, products and/or services.

IT Governance: 1) Locus of IT decision-making authority (narrow definition). 2) The distribution of IT decision-making rights and responsibilities among different stakeholders in the organization, and the rules and procedures for making and monitoring decisions on strategic IT concerns (comprehensive definition).

IT Governance Comprehensiveness: Degree to which IT decision-making/-monitoring activities are systematically and exhaustively addressed.

IT Governance Formalization: Degree to which IT decision-making/-monitoring follows specified rules and standard procedures.

IT Infrastructure: The base foundation of the IT portfolio, delivered as reliable shared services throughout the organization, and centrally directed, usually by corporate IT management.

IT Governance Integration: Degree to which business and IT decisions are integrated administratively, sequentially, or reciprocally.

IT Portfolio: Portfolio of investments and activities regarding IT operations and IT developments spanning IT infrastructure (technical and organizational components) and IT applications.

Participation: Process in which influence is exercised and shared among stakeholders, regardless of their formal position or hierarchical level in the organization.

Shared Learning: The co-creation of mutual understanding by members of organizational sub-units of each other’s goals and objectives.