INTRODUCTION

The last 15 years have seen the emergence on the software market of a category of software called Enterprise Resource Planning systems or ERP, which has become the focus of both researchers and practitioners in the information systems area. At this time, the ERP software market is one of the fastest growing markets in the software industry with long-term growth rates of 36-40%. Some estimates put the eventual size of the market by the year 2010 at US$1 trillion (Bingi et al., 1999). Since these estimates have been put forward, the ERP market has slowed down, but the overall growth of the enterprise-wide application market is still quite strong, thanks to a number of additional segments, such as Customer Relationship Management (CRM) and Supply Chain Management (SCM). Also, more recently, a new trend is emerging in the market: the re-implementation and extension of ERP, referred to as ERP II (Humphries and Jimenez, 2003). Fundamentally, ERPs are all integrated “mega packages” (Gable et al., 1997) which provide support for several or all functional areas of the firm depending upon the configuration purchased by the client. Their complexity is reflected in the complexity of their implementation and deployment in organisations where they have been observed to have a substantial impact on everyday activities in both the short term and the long term. This has led to many reports of unsuccessful implementation, which are however matched by many reports of substantial benefits accruing to implementing firms. Thus, managers look upon ERP software as necessary evils and much research has been carried out in order to increase the success rate of ERP implementations and to ensure that benefits materialize.

THE EMERGENCE OF ERP

The historical origin of ERP is in inventory management and control software packages that dictated system design during the 1960s (Kalakota and Robinson, 2001). The 1970s saw the emergence of Material Requirements Planning (MRP) and Distribution Resource Planning (DRP),which focused on automating all aspects of production master scheduling and centralised inventory planning, respectively (Kalakota and Robinson, 2001). During the 1980s, the misnamed MRPII (Manufacturing Resource Planning) systems emerged to extend MRP’s traditional focus on production processes to other business functions, including order processing, manufacturing, and distribution (Kalakota and Robinson, 2001). In the early 1990s, MRPII was further extended to cover areas of Engineering, Finance, Human Resources, Project Management, etc. MRPII is a misnomer, as it provided automated solutions to a wide range of business processes, not just those found within a company’s manufacturing and distribution functions (Kalakota and Robinson, 2001). However, although MRP II systems overcame some of the drawbacks of MRP systems they became less relevant because:

• Manufacturing is moving away from a “make to stock” situation and towards a “make to order” ethos where customisation is replacing standardisation. This has lead to a far more complex planning process.

• Quality and cost are only minimum requirements for organisations wishing to compete in the marketplace. Competition has moved to a basis of aggressive delivery, lead-times, flexibility and greater integration with suppliers and customers with greater levels of product differentiation.

As a result, MRPII was further extended and renamed ERP (Kalakota and Robinson, 2001). An ERP system differs from the MRPII system, not only in system requirements, but also in technical requirements, as it addresses technology aspects such as graphical user interface, relational database, use of fourth generation language, and computer-aided software engineering tools in development, client/server architecture, and open-systems portability (Russell and Taylor, 1998; Watson and Schneider, 1999). Also, while “MRP II has traditionally focused on the planning and scheduling on internal resources, ERP strives to plan and schedule supplier resources as well, based on the dynamic customer demands and schedules” (Chen, 2001). This brief evolutionary definition of ERP is depicted in Figure 1.

Kalakota and Robinson (2001) position ERP as the second phase in the “technology” and “enterprises internal and external constituencies” integration process, as illustrated in Figure 1. According to Kalakota and Robinson (2001), Wave 1 of the evolution of ERP addresses the emergence of Manufacturing Integration (MRP), while Wave 2 relates to Enterprise Integration (ERP). The combined impact of “key business drivers” (replacing legacy systems, gaining greater control, managing globalisation, handling regulatory change, and improving integration of functions across the enterprise) forced the “structural migration” from MRP to ERP (Kalakota and Robinson, 2001). Another significant factor in the second wave of ERP development was Y2K preparation, which was often cited as the major reason for ERP adoption (Brown et al., 2000; Kalakota and Robinson, 2001; Themistocleous et al., 2001). A new wave, Wave 5, now exists and positions ERP II as the new approach to enterprise integration.

ERP DEFINED

Although there is no agreed-upon definition for ERP systems, their characteristics position these systems as integrated, all-encompassing (Markus and Tanis, 2000; Pallatto, 2002), complex mega packages (Gable et al., 1997) designed to support the key functional areas of an organisation. The American Production and Inventory Control Society (APICS) defines ERP as, “an accounting-oriented information system for identifying and planning the enterprise-wide resources needed to take, make, ship, and account for customer orders” (Watson and Schneider, 1999). As a result, by definition, ERP is an operational-level system. Therefore, an Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system is a generic term for an integrated enterprise-wide standard information system (Watson and Schneider, 1999) that impounds deep knowledge of business practices accumulated from vendor implementations throughout organisations (Shang and Seddon, 2000).

ERP can be further defined as a strategic business solution that integrates all business functions, including manufacturing, financial, and distribution (Watson and Schneider, 1999). ERP systems are also being referred to as “enterprise systems” (Davenport, 1998; Chen, 2001) and “enterprise-wide Information Systems” (Al-Mashari, 2000; Milford and Stewart, 2000). It is a customised, packaged, software-based system that handles the majority of an enterprise’s information systems’ requirements (Watson and Schneider, 1999). It is a software architecture that facilitates the flow of information among all functions within an enterprise (Watson and Schneider, 1999). As a result, ERP systems are traditionally thought of as transaction-oriented processing systems (Davenport, 1998; Chen, 2001) or transactional backbones (Kalakota and Robinson, 2001). However, they are continually redefined based on the growing needs of organisations. Therefore, various definitions point to ERP systems as being enterprise-wide information systems that accommodate many features of an organisation’s business processes. They are highly complex, integrated systems, which require careful consideration before selection, implementation, and use. Neglect of any of these areas can lead a company down the path to failure already worn by FoxMeyer, Unisource Worldwide Inc., etc. (Adam and Sammon, 2004).

Figure 1. Evolution of ERP Systems

INSIDE ERP SYSTEMS

ERP systems use a modular structure (i.e., multi-module) to support a broad spectrum of key operational areas of the organisation. According to Kalakota and Robinson (2001), the multiple core applications comprising an ERP system are “themselves built from smaller software modules that perform specific business processes within a given functional area. For example, a manufacturing application normally includes modules that permit sales and inventory tracking, forecasting raw-material requirements, and planning plant maintenance.” Typically, an ERP system is integrated across the enterprise with a common relational database, storing data on every function. ERP are widely acknowledged as having the potential to radically change existing businesses by bringing improvements in efficiency, effectiveness, and the implementation of optimised business processes (Rowe, 1999). One of the key reasons why managers have sought to proceed with difficult ERP projects is to end the fragmentation of current systems, to allow a process of standardisation, to give more visibility on data across the entire corporation and, in some cases, to obtain competitive advantage (Adam and Sammon, 2004).

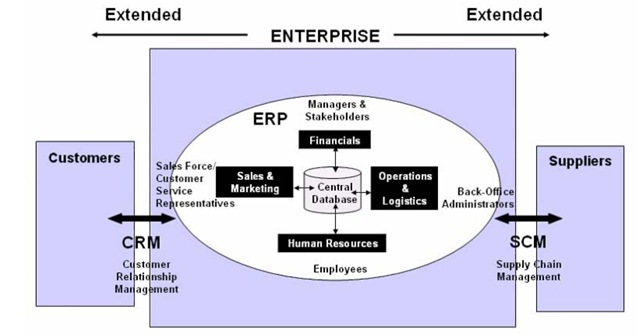

ERP systems have expanded to include “back office” functions, such as operations, logistics, financials or human resources and “non-transaction-based systems” (Davenport, 1998) or “front office” functions, such as sales, marketing, customer services as an integral component (Davenport, 1998; Chen, 2001). This inclusion is a result of the emergence of Supply Chain Management (SCM) (Chen, 2001; Turban, et al., 2001) and Customer Relationship Management (CRM) strategies and systems (Chen, 2001), as illustrated in Figure 2.

While the names and numbers of modules of the ERP systems available on the market may differ, a typical system integrates all its functions by allowing modules to share and transfer information freely and by centralizing all information in a single database (Chen, 2001). Figure 3 provides an overview of such an ERP system.

ERP packages force an organisation to implement a proven set of business processes, which means that there is no need for the organisation to “reinvent the wheel.” ERP packages encapsulate reusable “best practice” business processes. As state of the art technology and processes move forward, purchasers of packaged software move with them (Weston, 1998; Krumbholz et al., 2001; Stefanou, 2000). ERP packages give the foundation to the business, thus the management can concentrate on “grabbing market share” (Weston, 1998). Kalakota and Robinson (2001) stress that the popularity of ERP systems stems from the fact that they appear to solve the challenges posed by portfolios of “disconnected, uncoordinated applications that have outlived their usefulness.”

These “legacy systems” provide one of the biggest drags on business productivity and performance because maintaining many different computer systems leads to enormous costs. These include: direct costs such as rationalisation, redundancy, re-keying, reformatting, updating, debugging, deleting, etc., but more importantly, include indirect costs such as a company’s purchasing and sales system which cannot communicate with its production/scheduling systems, leading manufacturing productivity and customer service to suffer. Crucially, management may be left to make vital decisions based on information from incompatible systems, thereby relying on instinct rather than sound business rationale.

Figure 2. ERP Extended

Figure 3. Module Overview of an ERP System

MacVittie (2001) identified three goals behind the implementation of an ERP system:

1. Integration of Financial Data: When managers depend on their function’s or unit’s perspective of financial data, conflicting interpretations will arise (e.g., Finance will have one set of sales figures while Marketing will have another). Using an ERP system provides a single version of sales.

2. Standardisation of Processes: A manufacturing company that has grown through acquisitions is likely to find that different units use different methods to build the same product. Standardising processes and using an integrated computer system can save time, increase productivity, and reduce head count. It may also enable collaboration and scheduling of production across different units and sites.

3. Standardisation of Human Resource Information: This is especially useful in a multi-site company. A unified method for tracking employee time and communicating benefits is extremely beneficial because it promotes a sense of fairness among the workforce as well as streamlining the company as a whole.

BENEFITS OF ERP

Clearly, a properly implemented ERP system can achieve unprecedented benefits for business computing (Watson and Schneider, 1999). However, some companies have difficulty identifying any measurable benefits or business process improvements (James and Wolf, 2000; Donovan, 2001). For example, Pallatto (2002) observed that some vendors and consultants are presently “soft-peddling” the term ERP due to bad experiences and management frustration, when original business goals and benefits were not achieved, with their ERP implementations.

Rutherford (2001) observed that only around 10% to 15% of ERP implementations deliver the anticipated benefits. According to James and Wolf (2000) companies that were able to identify benefits thought that they could have been realized without the implemented ERP system. They felt that most the benefit they got from their ERP came from changes, such as inventory optimization, which could have been achieved without investing in ERP (James and Wolf, 2000). Therefore, ERP systems can be considered as a catalyst for radical business change that results in significant performance improvement (Watson and Schneider, 1999). According to James and Wolf (2000), reporting on an instance of an ERP implementation, “many of the benefits that we are able to achieve today could not have been predicted at the time that we started work on ERP. In fact, in hindsight it appears that much of the value of these large systems lay in the infrastructure foundation they created for future growth based on Information Technology.”

Shang and Seddon (2000) presented a comprehensive framework of business benefits that organisations might be able to achieve from their use of ERP systems. They present 21 ERP benefits consolidated across five benefit dimensions (operational, managerial, strategic, IT infrastructure, organizational). Shang and Seddon (2000) analyzed the features of ERP systems, literature on IT benefits, Web-based data on 233 ERP-vendor success stories, and interviews with 34 ERP cases to provide a comprehensive foundation for planning, justifying and managing the ERP system. The focus and goal of the Shang and Seddon (2000) framework is “to develop a benefits classification that considers benefits from the point of view of an organisation’s senior management” and that can be used as a “communication tool and checklist for consensus-building in within-firm discussions on benefits realisation and development” (Shang and Seddon 2000).

Shang and Seddon (2000) also commented that there were few details of ERP-specific benefits in academic literature and that “trade-press articles” and “vendor-published success stories” were the major sources of data. However, they warned that, “cases provided by vendors may exaggerate product strength and business benefits, and omit shortcomings of the products.” This was also observed in Adam and Sammon’s (2004) study of the “ERP Community” and the sales and needs discourse that characterise it. It is therefore extremely important to be able to assess the suitability of the ERP system for any organization. A study conducted by Sammon and Lawlor (2004) reiterates this argument, highlighting that failure to carry out an analysis of the mandatory and desirable features required in a system with an open mind will lead to the blind acceptance of the models underlying the ERP packages currently on sale on the market, with detrimental effects on the organization and its operations.

The justification for adopting ERPs centres around their business benefits. However, Donovan (1998) believes that to receive benefit from implementing ERP there must be no misunderstanding of what it is about, or underestimation of what is involved in implementing it effectively, and even more importantly, organisational decision makers must have the background and temperament for this type of decision making (Donovan, 2001).

CONCLUSION

Kalakota and Robinson (1999) put forward four reasons why firms are prepared to spend considerable amounts on ERP systems:

1. ERP systems create a foundation upon which all the applications a firm may need in the future can be developed.

2. ERP systems integrate a broad range of disparate technologies into a common denominator of overall functionality.

3. ERP systems create a framework that will improve customer order processing systems, which have been neglected in recent years.

4. ERP systems consolidate and unify business functions such as manufacturing, finance, distribution and human resources.

Thus, despite the slowdown of ERP package sales from 1999 on (Remy, 2003), there is evidence that the trend towards ERP and extended ERP systems is well established (Stefanou, 2000). Some segments of the ERP market maybe saturated, but powerful driving forces including e-commerce (Bhattacherjee, 2000), Enterprise Application Integration (EAI) (Markus, 2001), Data Warehousing (DW) (Inmon, 2000; Markus, 2001; Sammon et al., 2003) and ERP II (Pallatto, 2002) will further push this market to new heights in years to come. This will mean that considerable proportions of the IT investment of many firms will converge towards ERP-type projects and that IS researchers need to pursue their efforts at developing better frameworks and better methodologies for the successful deployment of Enterprise Systems in firms.

KEY TERMS

APICS: The American Production and Inventory Control Society was founded in 1957 and is a global leading provider of information and services in production and inventory management.

ERP Community: A model defining the collective relationships and interactions between the three de facto actors (the ERP vendor, the ERP consultant, the implementing organization) within the ERP market.

ERP II: ERP II is understood to mean the re-implementation and expansion of ERP. It is an extended, open, vertical, and global approach to systems integration and can be understood as an application and deployment strategy for collaborative, operational, and financial processes within the enterprise and between the enterprise and key external partners and markets, in an effort to provide deep, vertical-specific functionality coupled with external connectivity.

Extended Enterprise: Understood as the seamless Internet-based integration of a group or network of trading partners along their supply chains.

Legacy Systems: Mission-critical “aging” systems that supported business functions for many years. However, they are no longer considered state-of-the-art technology and have limitations in design and use. Within organisations, the vast majority were replaced pre-Y2K with ERP systems.

Modular System Design: An ERP system can be broken down by functional area (e.g., sales, accounting, inventory, purchasing, etc.). It increases flexibility in terms of implementing mutli-module (from one or many vendors), or single-module ERP functionality.

Return On Investment (ROI): A technique used for measuring the return on an investment and is often used in the justification of new ERP systems, or to measure how well an ERP system has been implemented, or for implementing new or additional functionality.