INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

The Information Systems (IS) field is dominated by research approaches and theories based in positivism (Arnott, Pervan, O’Donnell, & Dodson, 2004; Chen &Hirschheim, 2004; Schultze & Leidner, 2003). IS scholars have pointed out weaknesses in these approaches and theories and in response different strands of post-modern theories and constructivism have gained popularity—see Lee, Liebenau, and DeGross, (1997), Trauth (2001), Whitman and Woszczynski (2004), and Michael Myers’ “Qualitative Research in Information Systems” (http:// www.qual.auckland.ac.nz). The approaches and theories argued for include interpretivism, ethnography, grounded theory, and theories like Giddens’ (1984) structuration theory and Latour’s (1987) actor-network theory. (For simplicity, we refer to these different approaches and theories as “post-approaches” and “post-theories” when distinction is not required).

Although these approaches and theories overcome some of the problems noted with “traditional” approaches and theories, they have at least three major weaknesses and limitations. First, their fascination with the voices of those studied leads to IS research as mere reportages and local narratives. Second, their focus on agency leads to them ignoring the structural (systemic) dimension—the agency/structure dimension is collapsed, leading to a flat treatment of the dimension. Third, their rejection of objec-tivist elements leads to problems when researching artifacts like IT-based IS. For elaborate critiques of post-approaches and post-theories, see Lopez and Potter (2001) and Archer, Bhaskar, Collier, Lawson, and Norrie (1998).

An alternative to traditional positivistic models of social science as well as an alternative to post-approaches and post-theories is critical realism (Bhaskar, 1978, 1989, 1998; Harre & Secord, 1972). Critical realism (CR) argues that social reality is not simply composed of agents’ meanings, but that there exist structural factors influencing agents’ lived experiences. CR starts from an ontology that identifies structures and mechanisms through which events and discourses are generated as being fundamental to the constitution of our natural and social reality. This article briefly presents critical realism and exemplifies how it can be used in IS research.

CRITICAL REALISM

Critical realism has primarily been developed by Roy Bhaskar and can be seen as a specific form of realism. Unfortunately, Bhaskar is an opaque writer, but clear summaries of CR are available in Sayer (2000) and Archer et al. (1998). CR’s manifesto is to recognize the reality of the natural order and the events and discourses of the social world. It holds that:

… we will only be able to understand—and so change— the social world if we identify the structures at work that generate those events or discourses. These structures are not spontaneously apparent in the observable pattern of events; they can only be identified through the practical and theoretical work of the social sciences. (Bhaskar, 1989, p. 2)

Bhaskar (1978) outlines what he calls three domains: the real, the actual, and the empirical. The real domain consists of underlying structures and mechanisms, and relations; events and behavior; and experiences. The generative mechanisms, residing in the real domain, exist independently of but capable of producing patterns of events. Relations generate behaviors in the social world. The domain of the actual consists of these events and behaviors. Hence, the actual domain is the domain in which observed events or observed patterns of events occur. The domain of the empirical consists of what we experience, hence, it is the domain of experienced events. Bhaskar (1978, p. 13) argues that:

…real structures exist independently of and are often out of phase with the actual patterns of events. Indeed it is only because of the latter we need to perform experiments and only because of the former that we can make sense of our performances of them. Similarly it can be shown to be a condition of the intelligibility of perception that events occur independently of experiences. And experiences are often (epistemically speaking) ‘out of phase’ with events—e.g., when they are misidentified. It is partly because of this possibility that the scientist needs a scientific education or training. Thus I [Bhaskar] will argue that what I call the domains of the real, the actual and the empirical are distinct.

CR also argues that the real world is ontologically stratified and differentiated. The real world consists of a plurality of structures and mechanisms that generate the events that occur.

USING CRITICAL REALISM IN IS RESEARCH

CR has primarily been occupied with philosophical issues and fairly abstract discussions. In recent years, attention has been paid to how to actually carry out research with CR as a philosophical underpinning—see Layder (1998), Robson (2002), and Kazi (2003). This section briefly presents how CR can be used in IS research by discussing how CR can be used in theory development and how CR can be used in IS evaluation research.

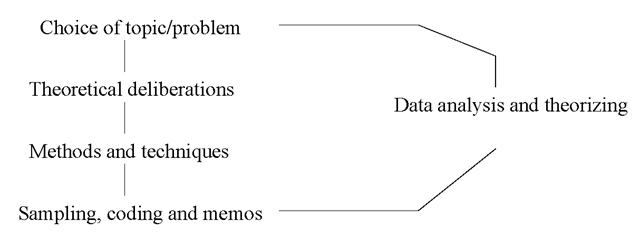

Bhaskar (1998) says that explanations (theories) are accomplished by the RRRE model of explanation comprising a four-phase process: (1) Resolution of a complex event into its components (causal analysis); (2) Rede-scription of component causes; (3) Retrodiction to possible (antecedent) causes of components via independently validated normic statements; and (4) Elimination of alternative possible causes of components. This is a rather abstract description of explanation development, and here we will instead use Layder’s (1998) less abstract “adaptive theory.” It is an approach for generating theory in conjunction with empirical research. It attempts to combine the use of pre-existing theory and theory generated from empirical data. Figure 1 depicts the different elements of the research process. There is not some necessary or fixed temporal sequence. Layder stresses that theorizing should be a continuous process accompanying the research at all stages. Concerning research methods and research design, CR is supportive of: (1) the use of both quantitative and qualitative methods, (2) the use of extensive and intensive research design, and (3) the use of fixed and flexible research design.

To exemplify how CR and Layder’s adaptive theory can be used in IS research, we will use a project on the use of Executive Information Systems (EIS). The project was done together with Dorothy Leidner.1 Here a new discussion of the research is carried out. The overall purpose of the study was to increase our understanding of the development and use of EIS, i.e., develop EIS theory.

Layder’s adaptive theory approach has eight overall parameters. One parameter says that adaptive theory “uses both inductive and deductive procedures for developing and elaborating theory” (Layder, 1998). The adaptive theory suggests the use of both forms of theory generation within the same frame of reference and particularly within the same research project. We generated a number of hypotheses (a deductive procedure), based on previous EIS studies and theories as well as Huber’s (1990) propositions on the effects of advanced IT on organizational design, intelligence, and decision making. These were empirically tested. From a CR perspective, the purpose of this was to find patterns in the data that would be addressed in the intensive part of the study. [For a discussion of the use of statistics in CR studies, see Mingers (2003).] We also used an inductive procedure. Although, previous theories as well as the results from the extensive part of the project were fed into the intensive part, we primarily used an inductive approach to generate tentative explanations of EIS development and use from the data. The central mode of inference (explanation) in CR research is retroduction. It enables a researcher, using induction and deduction, to investigate the potential causal mechanisms and the conditions under which certain outcomes will or will not be realized. The inductive and deductive procedures led us to formulate explanations in terms of what mechanisms and contexts would lead (or not lead) to certain outcomes—outcomes being types of EIS use with their specific effects.

Another parameter says that adaptive theory “embraces both objectivism and subjectivism in terms of its ontological presuppositions” (Layder, 1998). The adaptive theory conceives the social world as including both subjective and objective aspects and mixtures of the two. In our study, one objective aspect was the IT used in the different EIS and one subjective aspect was perceived effects of EIS use.

Figure 1. Elements of the research process (Layder, 1998)

Two other parameters say that adaptive theory “assumes that the social world is complex, multi-faceted (layered) and densely compacted” and “focuses on the multifarious interconnections between human agency, social activities, and social organization (structures and systems)” (Layder, 1998). In our study, we focused the “interconnections” between agency and structure. We addressed self (e.g., perceptions of EIS), situated activity (e.g., use of EIS in day-to-day work), setting (e.g., organizational structure and culture), and context, (e.g., national culture and economic situation). Based on our data, we can hypothesize that national culture can in certain contexts affect (generate) how EIS are developed and used and how they are perceived. We can also hypothesize that organizational “strategy” and “structure” as well as “economic situation” can in certain contexts affect (generate) how EIS are developed and used and how they are perceived.

Our study and the results (theory) were influenced by, e.g., Huber’s propositions, the “theory” saying that EIS are systems for providing top managers with critical information, and Quinn’s competing values approach (Quinn, Faerman, Thompson, & McGrath, 1996). The latter theory was brought in to theorize around the data from the intensive (inductive) part of the study. Adaptive theorizing was ever present in the research process. In line with CR, we tried to go beneath the empirical to explain why we found what we found through hypothesizing the mechanisms that shape the actual and the events. Our study led us to argue that it is a misconception to think of EIS as systems that just provide top managers with information. EIS are systems that support managerial cognition and behavior—providing information is only one of several means, and it can be one important means in organizational change. Based on our study, we “hypothesize” that “tentative” mechanisms are, for example, national culture, economic development, and organizational strategy and culture. We also hypothesized how the mechanisms together with different actors lead to the development and use of different types of EIS, for example, EIS for personal productivity enhancement respectively EIS for organizational change.

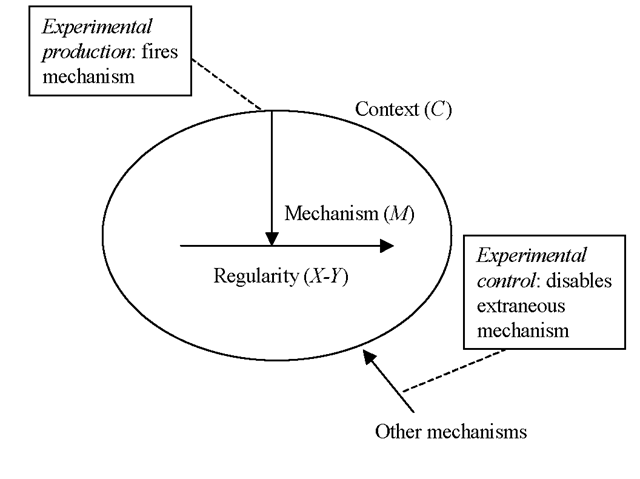

Figure 2. Realistic experiment (Pawson & Tilley, 1997)

IS evaluation (research) is of critical concern to practitioners and academics. Pawson and Tilley (1997) and Kazi (2003) advocate evaluation approaches that draw on the principle of CR and which, according to Bryman (2001, p. 40) see:

.the outcome of an intervention [like the implementation of an EIS] as the result of generative mechanisms and the contexts of those mechanisms. A focus of the former element entails examining the causal factors that inhibit or promote change when an intervention occurs.

Driving realistic IS evaluation research is the goal to produce ever more detailed answers to the question of why an IS initiative—e.g., an EIS implementation—works, for whom, and in what circumstances. This means that evaluation researchers attend to how and why an IS initiative has the potential to cause (desired) changes. Realistic IS evaluation research is applied research, but theory is essential in every aspects of IS evaluation research. The goal is not to develop theory per se, but to develop theories for practitioners, stakeholders, and participants.

A realistic evaluation researcher works as an experimental scientist, but not according to the logics of the traditional experimental research. Said Bhaskar (1998, p. 53):

The experimental scientist must perform two essential functions in an experiment. First, he must trigger the mechanism under study to ensure that it is active; and secondly, he must prevent any interference with the operation of the mechanism. These activities could be designated as ‘experimental production’ and ‘experimental control.’

Figure 2 depicts the realistic experiment.

Realistic evaluation researchers do not conceive that IS initiatives “work.” It is the action of stakeholders that makes them work, and the causal potential of an IS initiative takes the form of providing reasons and resources to enable different stakeholders and participants to “make” changes. This means that a realistic evaluation researcher seeks to understand why an IS initiative works through an understanding of the action mechanisms. It also means that a realistic evaluation researcher seeks to understand for whom and in what circumstances (contexts) an IS initiative works through the study of contextual conditioning. Realistic evaluation researchers orient their thinking to context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configurations. A CMO configuration is a proposition stating what it is about an IS initiative (IS implementation) that works, for whom, and in what circumstances. A refined CMO configuration is the finding of IS evaluation research—the output of a realistic evaluation study.

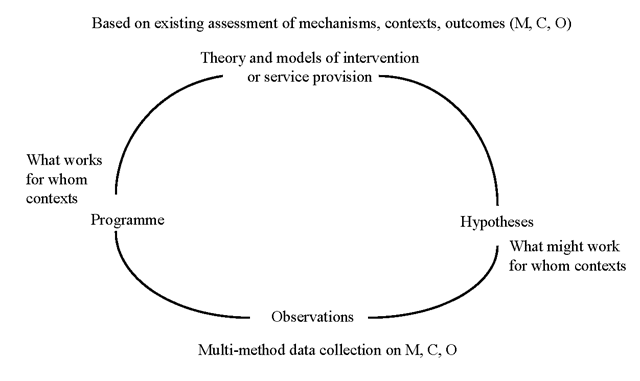

Figure 3. Realistic effectiveness cycle (Kazi, 2003; Pawson & Tilley, 1997)

Realistic IS evaluation based on the above may be implemented through a realistic effectiveness cycle (Kazi, 2003; Pawson & Tilley, 1997) (see Figure 3). The starting point is theory. Theory includes proposition on how the mechanisms introduced by an IS invention into preexisting contexts can generate desired outcomes. This entails theoretical analysis of mechanisms, contexts, and expected outcomes. This can be done using a logic of analogy and metaphor. The second step consists of generating “hypotheses.” Typically, the following questions would be addressed in the hypotheses: (1) what changes or outcomes will be brought about by an IS intervention?; (2) what contexts impinge on this?; and (3) what mechanisms (social, cultural and others) would enable these changes, and which one may disable the intervention? The third step is the selection of appropriate data collection methods—realists are committed to methodological pluralism. In this step it might be possible to provide evidence of the IS intervention’s ability to change reality. Based on the result from the third step, we may return to the programme (the IS intervention) to make it more specific as an intervention of practice. Next, but not finally, we return to theory. The theory may be developed, the hypotheses refined, the data collection methods enhanced, etc. This leads to the development of transferable and cumulative lessons from IS evaluation research.

CONCLUSION AND FURTHER RESEARCH

This article argued that CR can be used in IS research. CR overcomes problems associated with positivism, constructivism, and postmodernism.

Although CR has influenced a number of social science fields 2 e.g., organization and management studies (Ackroyd & Fleetwood, 2000; Reed, 2003; Tsang & Kwan, 1999; Tsoukas, 1989) and social research approaches and methods (Byrne, 1998; Robson, 2002), it is almost invisible in the IS field. CR’s potential for IS research has been argued by, for example, Carlsson (2003a, 2003b, 2004),Dobson (2001a, 2001b), Mingers (2003, 2004a, b), and Mutch (2002). They argue for the use of CR in IS research and discuss how CR can be used in IS research.

Bhaskar has further elaborated on CR, and in the future, his more recent works, e.g., Bhaskar (2002), could be explored in IS research.

KEY TERMS

Constructivism (or Social Constructivism): Asserts that (social) actors socially construct reality.

Context-Mechanism-Outcome Pattern: Realist evaluation researchers orient their thinking to context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) pattern configurations. A CMO configuration is a proposition stating what it is about an IS initiative that works, for whom, and in what circumstances. A refined CMO configuration is the finding of IS evaluation research.

Critical Realism: Asserts that the study of the social world should be concerned with the identification of the structures and mechanisms through which events and discourses are generated.

Empiricism: Asserts that only knowledge gained through experience and senses is acceptable in studies of reality.

Positivism: Asserts that reality is the sum of sense impression—in large, equating social sciences with natural sciences. Primarily uses deductive logic and quantitative research methods.

Postmodernism: A position critical of realism that rejects the view of social sciences as a search for overarching explanations of the social world. Has a preference for qualitative methods.

Realism: A position acknowledging a reality independent of actors’ (including researchers’) thoughts and beliefs.

Realist IS Evaluation: Evaluation (research) based on critical realism aiming at producing ever more detailed answers to the question of why an IS initiative works (better), for whom, and in what circumstances (contexts).

Retroduction: The central mode of inference (explanation) in critical realism research. Enables a researcher to investigate the potential causal mechanisms and the conditions under which certain outcomes will or will not be realized.