Next we consider multimedia documents: audio recordings and photographic images; video, which includes both image and audio components; and musical objects that can be presented in several different forms.

Sound and pictures

Some years ago, the public library in Hamilton, New Zealand, the small town where we live, began a project to collect local history. Concerned that knowledge of what it was like to grow up in Hamilton in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s would soon be permanently lost, the library decided to arrange to interview older people about their early lives. Armed with tape recorders, local volunteers conducted semi-structured interviews with residents of the region and accumulated many cassette tapes of recorded reminiscences, accompanied by miscellaneous photographs from the interviewees’ family albums. From these tapes, the interviewers developed a brief typewritten summary of each interview, dividing it into sections representing themes or events covered in the interview. But then the collection sat in a cardboard box behind the library’s circulation desk, largely unused.

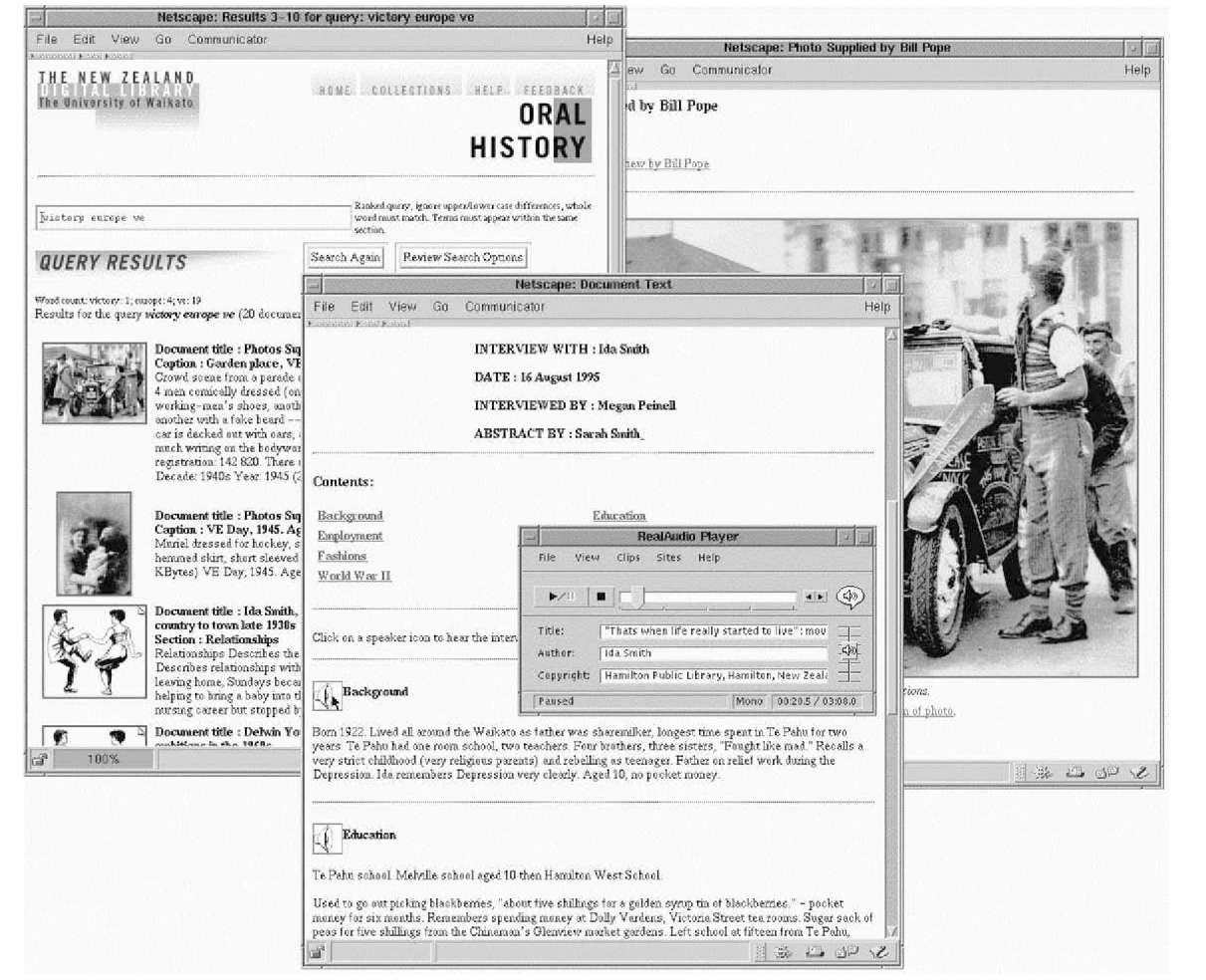

In a subsequent round of development, all the tapes and photos, along with the summaries, were digitized and made into a digital library collection. Figure 3.6 shows it in use. The user is listening to a particular recording using a standard software audio-player that has regular tape-recorder functions (pause, fast forward, and so on) on the small control panel in the center. Users don’t have to wait until the whole file is downloaded: the beginning starts playing while the rest is being transmitted. Behind the control panel is the interview summary. In the background on the right can be seen a photograph—in this case, of the town’s celebrations on VE Day (Victory in Europe) near the end of the Second World War—and on the left is the query page that was used to locate this information.

The interview page is divided into sections, with a summary for each. Clicking on one of the speaker icons plays back the selected portion of the audio; interviews also can be played in full using buttons at the top of the page (not visible in Figure 3.6). When the tapes were digitized, timings were generated for the beginning and end of each section. Flipping through a recording in this way, scanning a brief textual synopsis and clicking on interesting parts to hear them, is far more engaging and productive than trying to scan an audiotape with a finger on the fast-forward button.

The contents of the interview pages are used for text searching. Although they do not contain full transcripts, many keywords that you might want to search on are included. In addition, brief descriptions of each photograph were entered, and they are also included in the text search. These value-adding activities were done by amateurs, not professionals. Standard techniques, such as deciding in advance on the vocabulary with which objects are described (i.e., using a controlled vocabulary) were not used. Nevertheless, users can easily find material of interest.

Figure 3.6: Listening to a tape from the Oral History collection.

Consider the difference between accessing a box of cassette tapes at the library’s circulation desk and searching the fully indexed, Web-accessible digital library collection depicted in Figure 3.6. Text searching makes it easy to find out what it was like at the end of the war, to study the development of a particular neighborhood, or to see if certain people are mentioned (and you can actually hear senior residents reminisce about these things). Casual inquiries and browsing are simple and pleasurable—in striking contrast to searching through a paper file, then a box of tapes, and finally trying to find the right place on the tape using a cassette player. In fact, although this collection can be accessed from anywhere on the Web, the audio files are available only on terminals in the local public library, because the interviewees were not asked for consent to broadcast their voices worldwide. The message here for those engaged in local history projects is: think big.

Video

Videos combine time-based information with a spatial image component. As with audio, time-based documents can be made more conveniently browsable by segmenting them, and videos can be automatically converted into sequences of thumbnails that correspond to scene changes. Web browsers can play video in a variety of formats, provided a suitable plug-in is installed; the digital library server can even offer users a choice of formats. The Flash video format (reviewed along with several others in topic 5) adopted by YouTube has enormous penetration: some surveys estimate that it is installed on 99 percent of Internet-capable computers (compared with 80 to 85 percent for its closest rivals).

In planning a digital library, such statistics are useful in deciding on the best way to deliver documents to the intended audience. Decisions need to be coupled with knowledge about what the delivery format can do (for instance, Can the video be started at particular time offset? How easily and faithfully can the source format be converted?).

The feasibility of downloading video over the Internet depends on technical factors like the bandwidth of the connection. Of course, a great deal of storage space will be required for a large collection. Perhaps the digital library designer should consider providing an audio-only representation initially. This requires far less bandwidth and, particularly in the case of fixed-camera interviews, still communicates the essential information. For movies with an important visual component, a story-board of images could convey important details at a fraction of the cost of video.

Searching video, like searching the oral history audio, requires appropriate descriptive text. And, as is discussed in Section 3.4, images can also be searched directly, using similarity based on analysis of the images themselves. This technique can be applied to key-frames chosen from the video either manually or automatically.

Music

As topic 1 describes, digital collections of music have the potential to capture popular imagination in ways that scholarly libraries never will. Two elements to creating such a resource that is interesting and entertaining to search and browse are (1) having different representations of the same music available, and (2) linking to external resources to locate additional, relevant information.

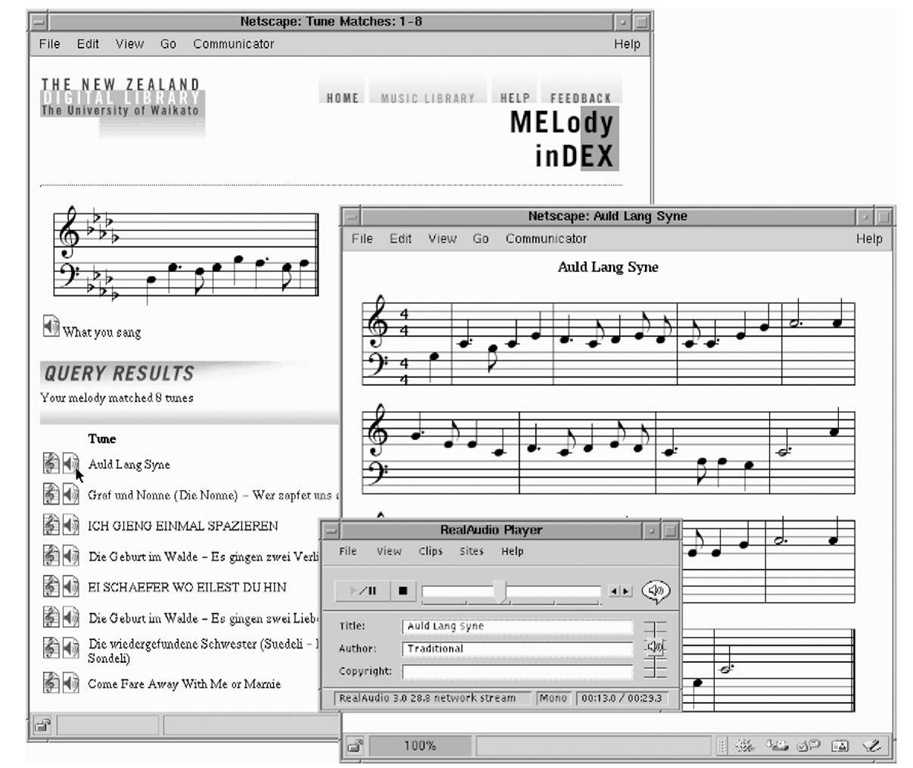

Figure 3.7 shows a prototype digital music library motivated by these observations. Starting with scanned images of sheet music, optical music recognition (OMR) software—which is similar to OCR software but works in the domain of printed music—was used to generate a symbolic version of each song. This was paired up with the original score and accompanying metadata for title, composer and lyricist. Searching and browsing capabilities were then developed based on this digital content.

In the figure we join a user partway through seeking for the tune Auld Lang Syne in the digital library, having sung a few remembered notes (we return to this "query by humming" capability in Section 3.4). For now we are interested in what can be done given the result of the query, which is a ranked list of songs that match precisely or are at least similar to the query. The further down the list a song is, the less likely it is to be the one the user is looking for.

Figure 3.7: Finding Auld Lang Syne in a digital music library

Clicking on the speaker icon to the top matching item (which in this case happens to be Auld Lang Syne) results in an audio rendition of the piece, based on the symbolic representation stored in the digital library. The player can be seen in the front window of Figure 3.7. The adjacent icon displays the musical notation for the tune (also featured in the figure), which was generated from the same internal representation, this time by a music-typesetting program.

For various reasons, this computer generated playback and typesetting can be of limited quality. Not shown in Figure 3.7, but just a click away for the user, is an image of the actual book page that contains the song. Also available are the lyrics. Furthermore, the song and artist metadata for a song are automatically hyperlinked to initiate text queries on the Web using a conventional general purpose Internet search engine: a convenient (but not necessarily precise) way to locate additional information about the song (or composer). It also enables other versions of the song to be found in, for instance, MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) format (see Section 5.6), or an actual recording (see Section 5.2) and one of those played instead.