The Internet, in particular the World Wide Web, lends itself well to anonymous access. Rather, it lends itself to the appearance of anonymous access. In practice, as many people have discovered to their cost, users are often more identifiable than they realize.

Anonymous use

Librarians have always been concerned about protecting both freedom of expression and the privacy of patrons. With regard to the former, Article IV of the Library Bill of Rights (Figure 2.1) requires librarians to cooperate with all persons and groups concerned with supporting (i.e., "resisting abridgement of") free expression and free access to ideas. With regard to the latter, Article III of the American Library Association’s Code of Ethics, reproduced in Figure 2.2, puts it very clearly: librarians must protect each user’s right to privacy and confidentiality with respect to information sought and resources used. Librarians around the world share the concerns of their American colleagues about ethical issues related to both censorship and privacy.

Most people believe that access to information benefits society as a whole. Public library services are provided without profit for society collectively—in other words, they are a "public good." The economist Paul Samuelson was the first to develop an economic theory of public goods, which he defined as ones that all [people] enjoy in common in the sense that each individual’s consumption of such a good leads to no subtractions from any other individual’s consumption of that good.

A so-called "pure" public good has the further property that no individual can be excluded from consuming it, which is particularly pertinent to Web-based digital libraries. It is hard to quantify the value to society of free access to information—or indeed the value of knowledge or education in general.

Libraries typically allow anonymous public access to physical resources, and also to some digital resources. Of course, in order to borrow materials it is necessary to provide some form of identification as surety. However, librarians guard the confidentiality of users to the greatest extent possible, on the basis that if confidentiality is compromised, freedom of inquiry is also compromised. If records of user activities are stored, it is possible that someone may later be able to retrace a user’s actions, including the search terms they used and the materials they accessed.

Code of Ethics of the American Library Association

As members of the American Library Association, we recognize the importance of codifying and making known to the profession and to the general public the ethical principles that guide the work of librarians, other professionals providing information services, library trustees and library staffs.

Ethical dilemmas occur when values are in conflict. The American Library Association Code of Ethics states the values to which we are committed, and embodies the ethical responsibilities of the profession in this changing information environment.

We significantly influence or control the selection, organization, preservation, and dissemination of information. In a political system grounded in an informed citizenry, we are members of a profession explicitly committed to intellectual freedom and the freedom of access to information. We have a special obligation to ensure the free flow of information and ideas to present and future generations.

The principles of this Code are expressed in broad statements to guide ethical decision making. These statements provide a framework; they cannot and do not dictate conduct to cover particular situations.

I. We provide the highest level of service to all library users through appropriate and usefully organized resources; equitable service policies; equitable access; and accurate, unbiased, and courteous responses to all requests.

II. We uphold the principles of intellectual freedom and resist all efforts to censor library resources.

III. We protect each library user’s right to privacy and confidentiality with respect to information sought or received and resources consulted, borrowed, acquired or transmitted.

IV. We respect intellectual property rights and advocate balance between the interests of information users and rights holders.

V. We treat co-workers and other colleagues with respect, fairness, and good faith, and advocate conditions of employment that safeguard the rights and welfare of all employees of our institutions.

VI. We do not advance private interests at the expense of library users, colleagues, or our employing institutions.

VII. We distinguish between our personal convictions and professional duties and do not allow our personal beliefs to interfere with fair representation of the aims of our institutions or the provision of access to their information resources.

VIII. We strive for excellence in the profession by maintaining and enhancing our own knowledge and skills, by encouraging the professional development of co-workers, and by fostering the aspirations of potential members of the profession.

American librarians are particularly concerned about demands being made by the government under the controversial USA Patriot Act, signed into law in October 2001, which increases the ability of law-enforcement agencies to search telephone, e-mail, medical, financial, and other records, including library records. Although some librarians suggest defiance, most agree that federal requests for data should be dutifully complied with, but only when a proper court order is served, and not just because a government agent asks for information. Of course, if fewer records are kept, less information can be provided. The Patriot Act does not require additional record keeping; only that anything that exists must be made available to federal authorities. Libraries usually keep minimal records and have a policy of erasing information immediately after use.

Anonymous access is one way of ensuring that users’ privacy is maintained. Patrons in physical libraries usually leave no trace of their actions (although some libraries have installed surveillance cameras, which itself has raised concerns about invasion of privacy). The same cannot be said for digital access, because electronic fingerprints are left in the user’s workstation and the library’s information system. However, remote access gives an impression of anonymity, and most users are unaware of the electronic trails they leave. Those who are aware do not worry unduly, because they expect that libraries will not pass on or otherwise misuse personal data.

Their confidence may be misplaced. Privacy issues in traditional physical libraries are clearly defined and well understood, if not always agreed upon. In contrast, the issue of privacy in a digital environment is murky. It is clear that users’ privacy is far less shielded from the librarian, or from those who have access to the library files, and users are therefore exposed to greater risk of disclosure from at least two sources: accidental mistakes and government agencies that can compel disclosure. Moreover, with digital technology the usage data that libraries acquire has potential interest not only for law-enforcement and security agencies, but also for commercial organizations and for the library itself, in order to assist with marketing.

Authenticated use

A practical issue in allowing public access to a digital library is whether one user’s activity interferes with others. We have all experienced Web sites that are slow to respond to requests. Response time is influenced by a variety of factors (e.g., network speed), but the presence of other users obviously makes systems less responsive. This effect can be mitigated in three ways:

• technical measures, ensuring that the software is configured appropriately

• economic measures, such as purchasing more computer power and faster connections

• social means, such as restricting access to identified users.

The first two measures may have little impact if the service is popular and the user base is uncontrolled.

When establishing a digital library, you must think carefully about whether you are aiming for public access—which inevitably means global access—or a specific target group of users. One compromise that has been adopted by many digital libraries is to permit public access to metadata but to restrict access to the full digital content to registered users.

Three simple methods of restricting services are:

• logical—restricting access to an organization’s network domain

• physical—restricting access to particular locations in the real world

• financial—restricting access to users who are prepared to pay (a "paywall").

Users may be asked to identify and authenticate themselves via usernames, passwords, or PINs, or by connecting to the system from pre-distributed software. In addition, users may have to supply bank account or credit card information.

While paid electronic services may seem to inevitably leave audit trails that can be used to trace the user, this is not necessarily so. Strange as it may seem, new information-security methods can arrange anonymous electronic cash transactions and guarantee the user’s privacy using mathematical techniques. These methods provide assurances that have a sound theoretical foundation (in contrast to security that depends on human devices like keeping passwords secret). Even a coordinated attack by a corrupt government with infinite resources at its disposal that has infiltrated every computer on the network, tortured every programmer, and looked inside every single transistor cannot force machines to reveal what is locked up mathematically. In the weird world of modern encryption, cracking security codes is the equivalent of solving puzzles that have stumped the world’s best minds for centuries. Whether electronic money transactions leave audit trails is not dictated by technology but remains a choice for society. Anonymity is an option that society has so far declined.

Digital libraries often provide management and administrative functions through Web sites. In these cases, authenticated or restricted use is essential; otherwise, users have the same power as managers and administrators. Section 2.5 explores how this idea can be used to dramatic effect to allow users to contribute to the library. Section 7.7 discusses authentication in more detail.

Recording usage data

The traditional way of recording usage in libraries is to record nothing at all. Nothing, that is, unless books are borrowed, in which case an anonymous date stamp was placed inside the front cover, as Figure 2.3 illustrates, and the librarian made a physical note. However, library lending is now administered by computer-based systems, moving usage records to the digital domain. In fact, digital records apply to many areas of society: daily activities such as credit card purchases, telephone calls, and airline ticket purchases are routinely stored for later analysis through techniques like data mining and cross-database linking. The patterns derived often reveal interesting information. In a digital library they might tell you what users are actually doing, as opposed to what you think they are doing. However, digital records can lead to unforeseen consequences.

Here’s an example. In August 2006, the Internet services company America Online (AOL) released to the research community the records of 20 million user searches. Their intention was laudable: they wanted to advance research on searching methods, which before then had been seriously handicapped by a lack of information about actual user behavior. Of course, all personal information had been removed from the records—or so AOL thought. But pretty soon journalists from the New York Times were able to identify that user number 4417749 was in fact Thelma Arnold of Lilburn, Georgia, USA (they sought her permission before exposing her). They did so by analyzing the search terms she used, which apparently ranged from numb fingers to 60 single men to dog that urinates on everything. Search by search, they reported, her identity became easier to discern. There were queries for landscapers in Lilburn, Ga, several people with the last name Arnold, and homes sold in shadow lake subdivision gwinnett county georgia, which reporters correlated with public databases, such as phonebooks.

This episode is a graphic illustration of the power of recorded usage data to reveal the identity of real people—even when the data has been anonymized. AOL quickly acknowledged its mistake and recalled the data. The repercussions were severe: their chief technical officer resigned, and two employees were reportedly fired. But you cannot erase information from the Web, and anyone can still download the AOL files from mirror sites. If you wish, you can easily find out more about Thelma Arnold’s interests.

Figure 2.3: recording usage with date stamps

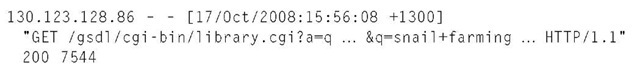

Web servers and digital library software all routinely include the capability to record the actions of users. A typical Web server log entry looks like this:

Log files can contain millions of such records—one for each time the Web server is accessed.

Here’s what this rather mysterious entry means. The four-part number at the beginning is the Internet Protocol (IP) address of the request, which could be the user’s computer or, more likely, a "proxy" server somewhere between the user and the Web server. The "—" on the first line sometimes gives the user id of the person requesting the document. This is determined by authentication using the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP); for almost all Web accesses, it is not defined—as in this case. Following a timestamp that specifies exactly when the request was made, the next part is the request type—in this case GET, which retrieves information from the Web server. (Another possibility is POST, which allows users to submit large quantities of data, such as uploading files.)

The next entry is the resource requested—in this case, to execute a program called /gsdl/cgi-bin/ library.cgi with certain specified arguments given after the question mark (discussed below), and to return the output. (More commonly, requests give a simple URL without any arguments, in which case the corresponding static Web page is returned.) Following that is the protocol used, in this case HTTP version 1.1. Then comes a status code: the 200 indicates a successful request (whereas 404 is sent when the server can’t find the requested information). Finally, the size of the response is indi-cated—a 7544-byte Web page was returned to the client.

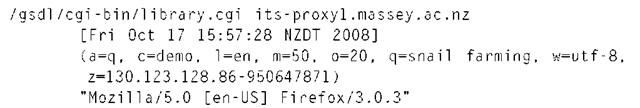

This particular example happens to request information from a digital library—the Greenstone digital library software (the /gsdl/cgi-bin/library.cgi part reveals this). In fact, it results in an entry in a second log file, the digital library’s own log:

Despite superficial differences, this log entry provides much the same information as the Web log entry discussed above. On 17 Oct 2008 a user at its-proxy1.massey.ac.nz (this computer has IP address [130.123.128.86]) sent a request to Greenstone. The nature of the request is encoded in the arguments (some were omitted from the earlier example purely to make it more digestible). Interpreting the arguments reveals that the user issued the query snail farming (q=snail farming). Other arguments request the result page in the English language (l=en) to the given query (action a=q), when searching the demo collection (collection c=demo). The user’s browser is Firefox version 3.03. Other arguments give the number of search results to be returned (m=50), the number displayed per page (o=20), and the encoding scheme used (w=utf-8). The last argument, z, is a "cookie" generated by the Web server: it is comprised of the user’s computer’s IP number followed by the time that it first accessed the digital library.

Can this information be used to identify the user? We know that the request came from its-proxy1. massey.ac.nz, which is a computer at Massey University in New Zealand. Its name indicates that it is a proxy server through which user requests are relayed, rather than a workstation on a particular user’s desktop. The proxy server keeps its own log, which we may be able to access—if we have a search warrant. Such information was, of course, removed from the AOL data. The most interesting part is the "cookie." Web cookies are short messages that are sent by a server to a Web browser and then sent back unchanged by the browser each time it accesses that server. This identifies the user— not by name, or as a particular person, but in a way that allows the system to tell whenever they make a subsequent request. (AOL anonymized the cookies in its data by replacing them with a unique user id—4417749 in the case of Thelma Arnold. However, as she discovered, users often can be identified by their queries.) In this case we might search out snail farmers in Palmerston North, New Zealand (where Massey University is). How many can there be?

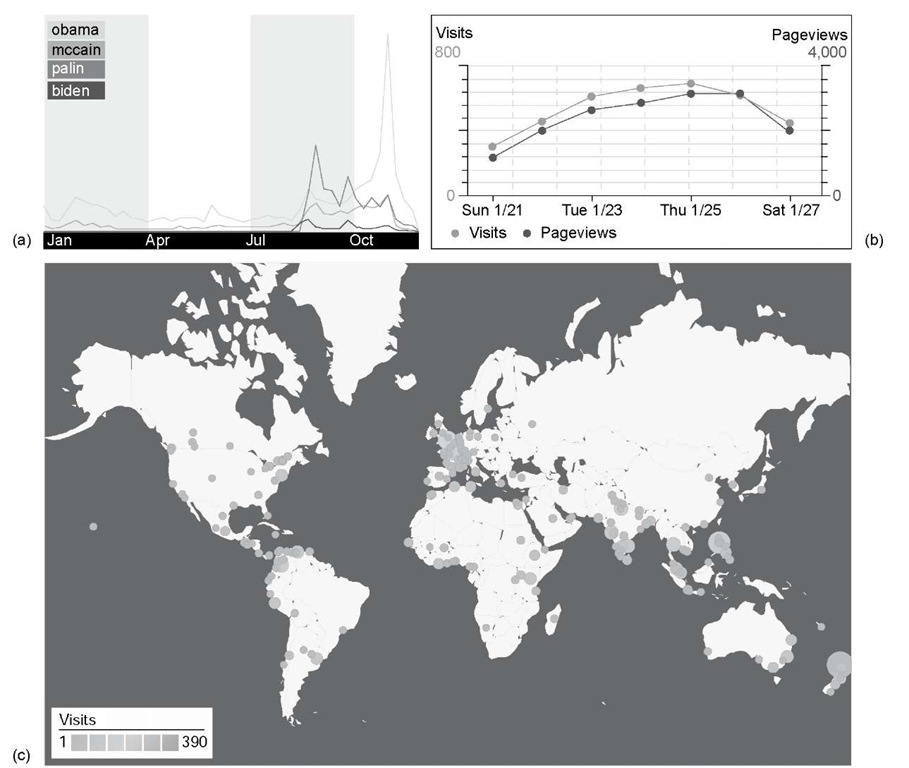

Specialist software is used to turn logs into concise summaries of Web server or digital library usage. For example, Figure 2.4a shows the number of searches for 2008 U.S. presidential candidates on Google throughout the election year. The major spike for Palin occurred when she was chosen as McCain’s vice-presidential running mate; that for Obama was when he was elected President. Figure 2.4b graphs the usage of a particular digital library site during a single week in 2007.

Figure 2.4: User log displays: (a) Google searches for U.S. presidential candidates during 2008

It plots both visits (a total of 3,800), defined as a sequence of requests from a uniquely identified client that expired after 30 minutes of inactivity, and page views (a total of 16,800), which are requests made to the Web server for a page. Figure 2.4c shows the geographical distribution of visitors.

Such data is useful for understanding what users are doing. It also reveals what technology they use to access your resources. If you wish to enhance your document presentation using particular features of Web browsers, it is good to know which browsers are actually being used.