Traditional libraries manage their holdings using catalogs that contain information about every object they own. Metadata, characterized in topic 1 as "data about data," is a recently coined term for this information. Metadata is information in a structured format and its purpose is to provide a description of other data objects in order to facilitate access to them. The data objects themselves (e.g., the books) generally contain unstructured information. Sometimes, as in the Humanity Development Library in Figure 3.1, they do have some internal structure. Sometimes, as in the Project Gutenberg collection in Figure 3.2, their information has structure but that structure is not apparent to the system. However, the essential feature of metadata is that its elements are structured. Moreover, metadata elements are standardized so that the same type of information can be used in different systems and for different purposes. In the computer’s full-text copy of a book, the title.However, when this information is represented in metadata, in a standard way using standard elements, the computer can identify these fields and operate on them.

When users initiate a search or browse in a digital library, they are often presented with lists or displays that summarize the digital objects themselves. These summaries are known as document surrogates, which are concise displays that represent the actual object, typically using some of its metadata.

Metadata

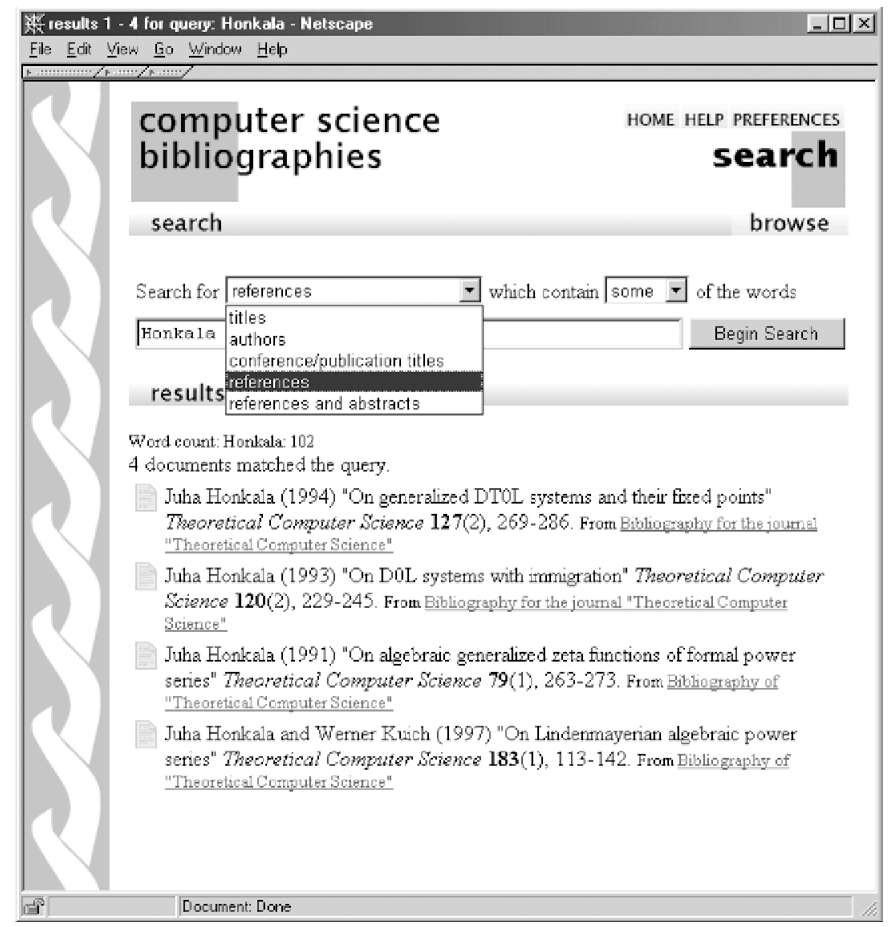

Figure 3.8 is taken from a digital library collection of computer science bibliographies. It shows the result of searching for the author Honkala, with matching publications presented as a standard bibliographic listing: the hyperlink at the end of each item links to the source bibliography. Many of the entries have abstracts, which are viewed by clicking the page icons to the left—although here they are grayed out, indicating that abstracts are unavailable. The metadata displayed includes title, author, date, the title of the publication in which the article appears, volume number, issue number, and page numbers. As noted above, it also includes the URL of the source bibliography and the abstract (although it is debatable whether this is structured enough to constitute metadata).

Metadata has many different aspects, corresponding to various kinds of information that might be available about an item. Historical features describe provenance, form, and preservation history. Functional ones describe usage, condition, and audience. Technical ones provide information that promotes interoperability between different systems. Relational metadata covers links and citations. And, most important of all, intellectual metadata describes the content or subject. Metadata provides assistance with search and retrieval; gives information about usage in terms of authorization, copyright, or licensing; addresses quality issues, such as authentication and rating; and promotes interoperability with other systems.

Figure 3.8: Bibliography display

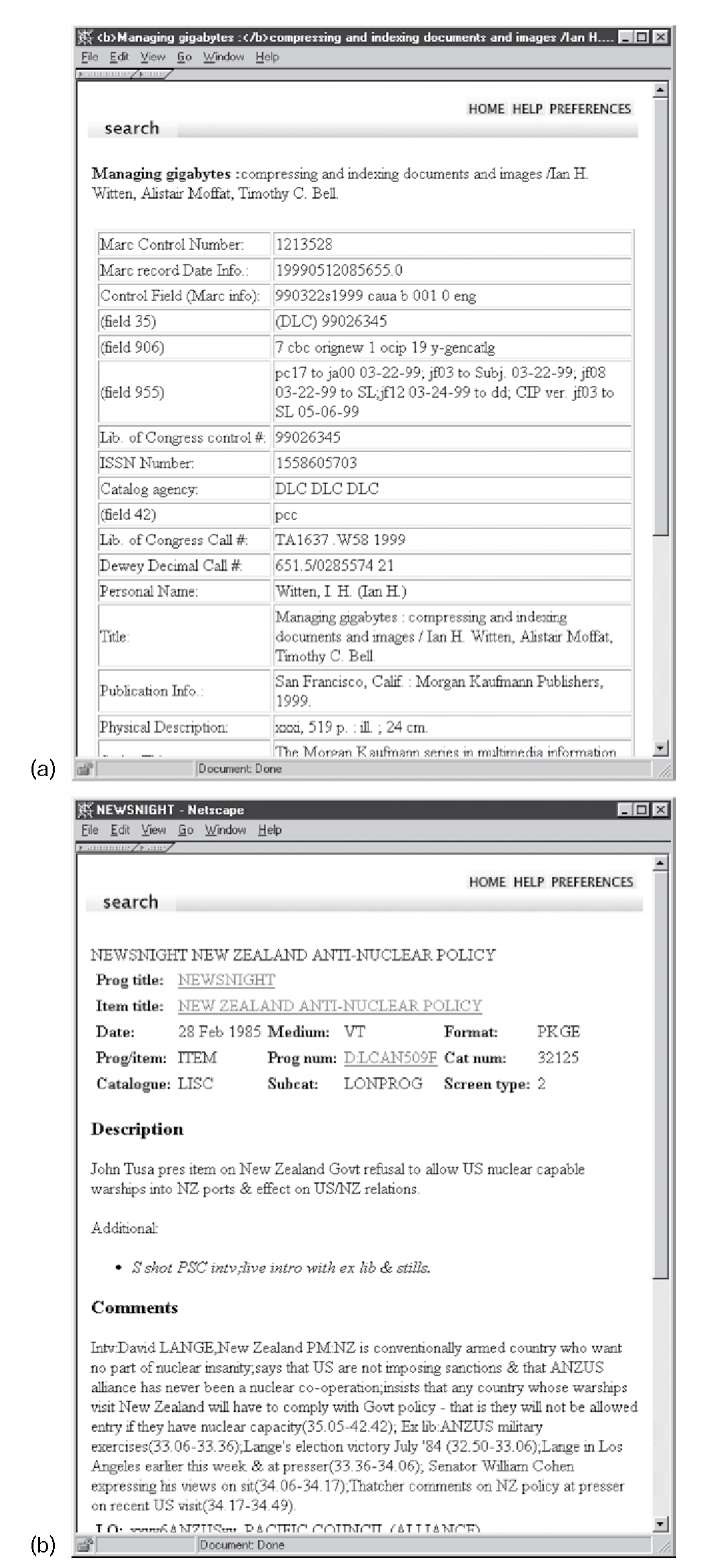

Figure 3.9a shows a record retrieved over the Internet from the Library of Congress and displayed within a simple interface (although only half of the fields in the record are visible). Common fields are named, while obscure ones are labeled with identification numbers (e.g., field 35). You can see that there is some redundancy: the principal author appears in both the Personal Name field and in a subfield of the title; the other authors also appear further down the record in separate Author Note-Name fields (not shown). This metadata was retrieved using an information interchange standard (called Z39.50) that is widely used throughout the library world (see Section 7.2) and is represented in a record format called MARC ( "machine-readable cataloging") that is also used by libraries internationally (see Section 6.2).

Library metadata is standardized, but, as is often the case with standards, there are many different ones to choose from. (MARC itself comes in more than 20 variants, produced for different countries.) Non-bibliographic metadata has no widely accepted standards. Figure 3.9b shows a record from a BBC catalog of radio and television programs; the record gives such information as program title, item title, date, medium, format, several internal identifiers, a description, and a comments field.

Figure 3.9: Metadata examples: (a) bibliography record retrieved from the Library of Congress; (b) description of a BBC television program

Metadata descriptions often grow willy-nilly, in which case the relatively unstructured technique of text search is a better way to locate records than using a conventional metadata database. Because of increased interest in communicating information about radio and television programs internationally, people in the field are working on developing a new metadata standard for this purpose. Developing international standards requires a lot of hard work, negotiation, and compromise; it takes years.

Surrogates can also include elements from the document’s actual content. A common method of displaying full-text search results is to highlight some matching text and to use it as part of the surrogate that is displayed to the user. For example, Figure 3.10 shows textual snippets from the documents in a page returned by the Google search engine. This allows users to see how their search terms interact with the document collection.

Multimedia surrogates

Textual surrogates rarely give users a good feeling for multimedia content, but some elements of multimedia can produce effective representations that help users make informed choices about which documents to investigate further. Even a predominantly textual document like a book can use its cover image as a surrogate.

It is natural to represent full-size images by miniature versions, and scaled or cropped thumbnails are effective surrogates. Temporal multimedia like audio and video are not so easily accommodated. Should an hour-long video be represented by a mini version of it? Which parts? All the way to the end? Users normally expect to be able to make selection decisions in just a few seconds, but if the surrogate appears among search results, they may face ten or twenty miniature videos.

For this reason, video surrogates are usually reduced to image key-frames or short clips (of a few seconds) that are under the user’s control. Similarly, well-chosen musical excerpts can stand in for an entire symphony. Alternatively, images of CD covers or artists can be used as visual surrogates of audio. Here are some general approaches used when there are no obvious surrogates, as with complex digital objects like animations, computer programs, and data sets:

• textual metadata

• miniature version of the content (e.g., cropped or scaled images)

• extract in a different media format (e.g., image key-frames from video)

• short extract from temporal media (e.g., video, audio, animations)

• related multimedia in another format (e.g., CD cover image)

• generic icon like the symbol for a particular document format or an image representing music.