Washington state is 71,300 sq. mi. (184,666 sq. km.), with inland water making up 1,553 sq. mi. (4,022 sq. km.), coastal water making up 2,535 sq. mi. (6,565 sq. km.), and access to territorial water making up 666 sq. mi. (1,725 sq. km.). Washington’s average elevation is 1,700 ft. (518 m.) above sea level, with a range in elevation from sea level on the Pacific Ocean to 14,410 ft. (4,392 m.) at the peak of Mt. Rainier. Western Washington lies on the Juan de Fuca Plate, with overriding by the North American Plate.

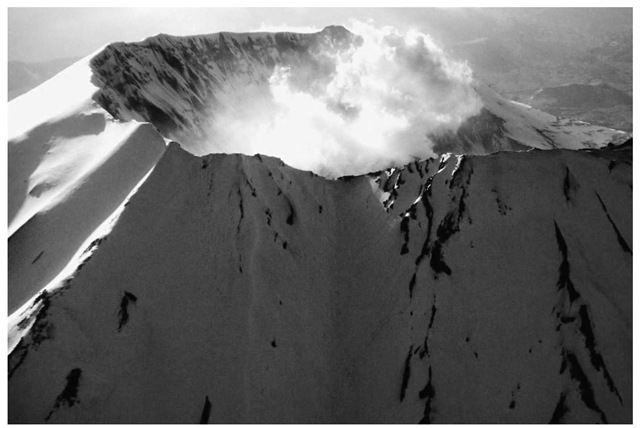

Washington is fairly warm and is kept that way by ocean currents including frequent rain and the rain shadow effect. Moist air streams up slopes of mountains, and rainfall or snowfall is increased. However, when the air, depleted of much of its moisture, begins to descend down the slopes, the temperatures warm, clouds dissipate, and very little precipitation falls. Western mountains take Pacific moisture that flows onshore all year long. The western slopes of the Olympic Mountains have a true rainforest, but the rain shadow on the eastern slope means it receives less than 15 in. of rain per year. The highest temperature recorded in the state is 118 degrees F (48 degrees C) in Ice Harbor Dam on August 5, 1961, and the lowest temperature recorded in the state is minus 48 degrees F (minus 44 degrees C) in Mazama and Winthrop on December 30, 1968. Mount St. Helens, an active volcano, spouted volcanic ash into the atmosphere in 1980. In 1993, the year of the flood in Iowa, Washington recorded the coolest summer on record in Spokane.

Mount St. Helens in Washington is an active volcano, and had an enormous eruption at 8:32 in the morning on May 18,1980. The debris blasted down nearly 230 sq. mi. (596 sq. km.) of forest and buried much of it beneath volcanic mud deposits.

The state supports a population of over 6 million people. Major industries include agriculture, with the major products being apples, beef, milk, timber, and wheat; manufacturing computers, food, machinery, and paper products; and mining coal, gold, sand, and gravel.

The Columbia River is the second largest river in the country based on volume. The Grand Coulee Dam retains some water from spring runoff for summer use. It is the largest concrete structure at 55 ft. (16.7 m.) tall. It holds 24 generators supplying 65 million kilowatts of electricity. This electricity is carried throughout the west and east to Chicago.

Commercial logging started in the 1800s and has claimed 90 percent of the forests that once grew in the Pacific Northwest. Logging in the national forests since World War II has divided mountainsides and river valleys into checkerboards of clear-cut and uncut forest, creating vulnerable areas to succumb to environmental pressures. More than half of the remaining untouched forest areas in Olympic National Forest are slated for cutting during the next 50 years, as is 69 percent of the old growth in Oregon’s Siuslaw National Forest. In 1990, Congress voided all court injunctions brought to stop cutting of ancient trees on lands administered in Washington and Oregon by the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service and removed the right of citizen and conservation groups to seek further injunctions in any future cuts planned.

The Climate Impacts Group at the University of Washington is working to further understanding of the patterns and predictability of regional climate variability, the influence of climate variation on the Pacific Northwest, and providing strategies to prepare for climate change.

Washington is a member of the Western Regional Climate Action Initiative, along with Arizona, California, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, and the Canadian provinces of British Columbia and Manitoba. This cooperative group works together to identify, evaluate, and implement ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions on the regional level.

The effects of climate change that are already being experienced by Washington include weather changes, reduced summer water supply dependent on winter snowpack, and rising water levels along the coastline. Because of these effects, Washington is taking steps to prepare for climate change and reduce human-induced contributions to global warming. In February 2007, the governor signed an executive order establishing goals for reduction in climate pollution, increases in jobs, and reductions in expenditures on imported fuel. Because the United States has not ratified the Kyoto Protocol calling for greenhouse gas emission reduction, some states and regions have taken voluntary initiatives to reduce these emissions on their own. Washington’s goal is to cut emissions by 20 percent by 2050, with reduced auto emissions, use of renewable fuels, green building standards, and energy efficiency; passing a clean renewable energy initiative; and adopting a CO2 emissions performance standard for electric generating units.

Not only is Washington proactive on reduced emissions but they provide education and call for public support by using more energy-efficient transportation (public transportation, ride sharing, walking, or bicycling), improving home energy efficiency (insulation, energy-efficient appliances, and fluorescent lighting), and encouraging the planting of trees and plants.

Though climate models show no precipitation change, a change in temperature of 2 degrees to 3 degrees may mean less snowfall. An expected decrease this century of 60 percent in Cascade snowpack—even in the most reassuring of global warming scenarios— stands to have devastating consequences in the Pacific Northwest. The Columbia River’s Grand Coulee Dam has made it possible for Washington, along with other Pacific and mountain states, to increase in population. A survey of nearly 600 snowfields in the Sierra Nevada, the Rocky Mountains, and the cascades of Washington and Oregon shows that 85 percent of them have lost volume since the 1950s. A higher incidence of wildfires resulting from increasing drought levels, as well as rising sea levels, could displace people from their homes.

The associated costs include those affiliated with fighting wildfires, flood damage, lost revenue from tourism, increase in water pricing because of shortages and drought conditions, and increased costs for healthcare related to poor air quality and increased infection.

With rising temperatures, variable precipitation, and rising sea levels, the quality of the water supply in Washington could be compromised, with an increasing risk of water-borne infections. The potential for agricultural disruption also could lead to risks of malnutrition, and increasing heat waves could cause more heat-related illness.