FROM THE TROPICS to Antarctica, penguins depend on predictable regions of high ocean productivity where their prey aggregate. There are between 16 and 19 species of penguins, all generally restricted to the southern hemisphere, with the greatest species diversity found in New Zealand. Changes in precipitation, sea ice, ocean temperature and productivity, and prey distributions associated with global climate warming are affecting penguins and changing their distribution and abundance. Bird Life International includes climate change among the threats for seven of 10 species of penguin listed as endangered or vulnerable.

Changes in precipitation, sea ice, and ocean temperature associated with global warming are affecting penguins.

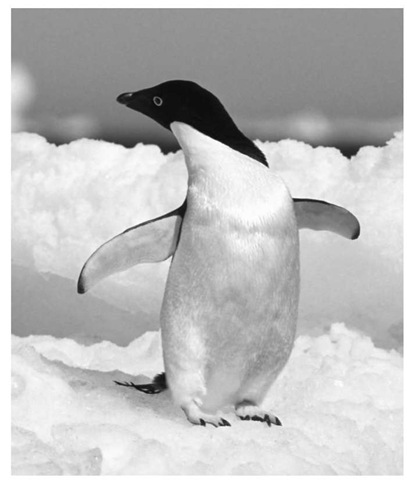

The global climate signal is strongest in the Antarctic Peninsula, where air temperature has increased, glaciers have retreated, and ice shelves have collapsed. Adelie and Emperor penguins, the most ice-associated and southerly of the penguin species, are suffering more reproductive failures because of increases in rain and snow, early breakup of ice, and blocking of colony access by icebergs. Gentoo and Chinstap penguins, more northerly and less ice-tolerant, have extended their ranges farther south, but suffer more failures because of increased precipitation. Snow covers nest sites and rain soaks the down of chicks, which then freeze. King penguins, the second largest species, harvested during the whaling era for their oil, have increased and expanded their range northward.

Many of the temperate species of penguins are in decline because of human perturbations including harvest, accidental capture by fisheries, petroleum pollution, breeding habitat destruction, and climate variation that changes the distribution and abundance of their prey. Temperate penguins also suffer from increases in rainfall or air temperatures, as young chicks cannot regulate their body temperatures when their down is wet. Increased frequency of El Nino events associated with global warming reduced Galapagos penguins to about half of what they were in the 1970s. During El Nino, the water warms, ocean productivity declines, and penguins quit breeding, and under the strongest and longest events, penguins die. Peruvian penguins declined after the 1972 El Nino and have never recovered, in large part because the anchovy fishery, the second largest fishery in the world after Alaskan Pollack, harvests much of their prey to make fishmeal.

Patagonian penguins, the most common of the temperate penguins, have declined by 22 percent since 1987 at their largest breeding colony, in Argentina. They swim farther north during incubation than they did a decade ago, likely a reflection of shifts in their prey in response to climate change and reductions in prey abundance due to commercial fishing. African penguins are only 10-20 percent of their previous number, because humans are harvesting more of the ocean’s produce than in the 1950s. African penguins are also shifting their breeding locations because of changes in prey distributions linked to climate. Breeding colonies in protected reserves are no longer near sources of food. Ocean productivity will likely continue to decline as climate warms, which is a problem for penguins, as they need areas of high productivity to survive. As global sentinels, penguins are showing that global climate change is creating new challenges for their populations.