A FLOOD IS the intrusion of water into normally dry land. While floods are a natural part of the ecological cycle and have some benefits for the health of the biosphere as a whole, flooding has always been one of the most devastating types of natural disasters for humans, responsible for thousands of deaths and billions of dollars in property damage each year. Climate change is expected to increase the risk of flooding for people around the world, both by raising global sea levels and increasing severe inland flooding events.

Flash flooding

Flash flooding is most commonly caused by heavy rainfall over a short period of time, from a tropical system or an unusually heavy thunderstorm event. Less common causes include dam and levee breeches or the release of ice jams. Flash floods come on quickly and with little warning, developing in less than six hours from the initial rain or water event. They can move with great speed and strength, uprooting trees, picking up large boulders, destroying bridges, roads, and homes in a matter of moments. Flash flooding is responsible for at least 80 percent of all weather-related deaths in the United States each year, mostly due to people becoming trapped in automobiles. As little as 2 ft. (0.6 m.) of water can lift and move a full-sized commercial vehicle.

Although flash flooding is commonly associated with canyons or narrow valleys, where geography dictates the flow of excess water, or arid regions where the ground is not able to rapidly absorb large amounts of rainfall; urban areas are often affected by the phenomena. Buildings and impervious surfaces such as roadways and parking lots collect tremendous amounts of rainfall and divert it into storm drains, which can quickly be overwhelmed, sending the overflow into communities that are often unprepared for the threat.

Globally, flash floods are responsible for an average of 5,000 deaths and millions of dollars of property damage each year. Many regions do not have the forecasting or notification technology to alert vulnerable populations to oncoming flood events. Since 2006, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has been working to implement a system known as the Flash Flood Guidance Center with Global Coverage, which would give developing countries greater ability to mitigate loss of life in flash-flooding events.

Inland and riverine flooding

Flooding within a watershed, or riverine flooding, is another common form of inland flooding. Like flash flooding, riverine flooding is generally caused by rainfall or runoff that is too heavy to be absorbed into the watershed, sending the water over the bounds of the river or stream’s banks and inundating nearby flood plains. Unlike flash floods, they build slowly, over a period of many hours or days, and last for a longer period of time, often more than a week, and sometimes over a month. Flooding along the Mississippi River Valley in 1993 lasted for 45 days, with some areas still partially flooded for 183 days; a flood event in Bangladesh in 1998 lasted for 68 days before finally receding.

Riverine flooding tends not to be as deadly as flash flooding, but causes great damage to property and agricultural lands, as was seen in the Mississippi Valley floods of 1993. High water displaced 70,000 people in nine states, damaged 50,000 homes, destroyed 12,000 acres of farmland, and caused an estimated $15 billion in losses.

Coastal flooding and storm surge

By 2006, an estimated 44 percent of the world’s 6.5 billion inhabitants lived within 93.2 mi. (150 km.) of a seacoast. Eight of the world’s 10 largest cities are coastal, including: New York, Tokyo, Shanghai, Kolkota, Sao Paulo, and Mexico City. This puts tens of millions of people at risk from coastal flooding and storm surge, with more people gravitating toward the oceans each year. As the Boxing Day Tsunami of 2004 illustrated, the impact of coastal flooding can be devastating: over 220,000 people around the Indian Ocean were killed in a single day.

A tsunami is a series of waves created by the displacement of water and is generally the result of geological events such as an undersea earthquake, a volcanic eruption, or a massive landslide. However, meteorological events are a much more common threat to coastal communities.

Coastal flooding occurs when the sea level rises above the normal tides, usually in response to an offshore storm or low-pressure system, but occasionally from significant runoff from nearby land. In its mildest forms, coastal flooding causes beach erosion, while moderate to major flooding can wash out roads and structures close to the shoreline. In coastal cities like New York, heavy coastal flooding can cause havoc by inundating the subway system and underground utilities, freezing transportation, and disrupting the power grid.

Storm surge is a phenomena tied to low-pressure systems such as tropical cyclones or hurricanes. The force of the winds inside a hurricane pushes the water up in front of it. This piling effect combines with normal tides, sometime rasing the mean water level by more than 15 ft. (4.5 m.). Wind and wave action turn this high water into a destructive force once they make landfall: 90 percent of all human deaths in hurricanes are cause by storm surge.

Importance in ecosystem

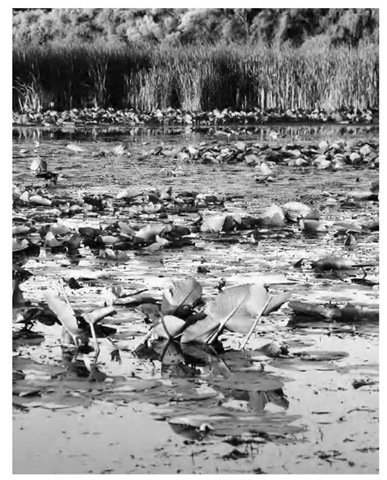

Flooding has long been recognized as vital part of the ecosystem. Floodwaters often carry sediment and nutrients along their path, nourishing the land wherever they are deposited. This builds valuable habitats for a variety of wildlife and vegetation, and rich alluvial soil for agricultural use. The earliest human civilizations arose on the flood plains of the Tirgis and Euphrates Rivers of Mesopotamia. For centuries, the regular flooding of the Nile River between July and September of each year deposited soils in Egypt’s narrow Nile River Delta, allowing the cultivation of crops that made the growth of Egyptian civilization possible.

Worldwide, riverine flood plains cover more than 772,204 sq. mi. (2 million sq. km.) of land and coastal flood plains cover much more land. Most are considered environmentally threatened; in the United States and Europe, almost 90 percent of riverine flood plains are under cultivation, making them, in the words of one researcher, "functionally extinct." One of the main reasons for the threat is the prevalence of flood controls such as dams, levees, impoundments, and flood gates, which protect human life and property, but often destroy natural flood cycles.

Human impact

The desire to prevent flooding is understandable, as floods are among the deadliest of natural disasters for humans. Between 1900 and 2004, an estimated 6.8 million people were killed by flood events. About 98 percent of these deaths occurred in Asia.

Floods affect human health and safety in several different ways. A rapid rise of water, from events such as flash flooding or a tsunami, can cause immediate death from drowning or injury. As floodwaters recede, injuries are joined by a greater risk of disease from contamination of drinking water tainted by raw sewage or pollutants. Cholera and other diarrheal diseases are common in the days and weeks after floods. Standing floodwaters can become breeding grounds for vector-borne diseases like malaria; displaced rodent and reptile populations can also cause illness and injury. Critical infrastructure such as hospitals, municipal water, sanitation, and food distribution systems are often destroyed in major flood events, leaving the displaced population at even greater risk.

Climate change and sea level rise

Predictions regarding sea-level rise are one of the most controversial aspects in climate science, with estimates ranging from a few inches to several meters. Dramatic images of the Statute of Liberty barely peeking above the waterline aside, there is little doubt that there will be a rise in the overall sea level over the coming century.

Water will expand as ocean temperatures rise, and the melting of the polar ice caps will contribute to the overall volume of water. But the rise is not uniform across all oceans, and the mechanisms that contribute to the rise are not yet clearly understood, casting doubt on all projections.

Sea levels have climbed 400 ft. (130 m.) in the past 18,000 years. For 3,000 years, the rate of that rise was .004-.008 in. (0.1-0.2 mm.) per year. Beginning in 1900, it climbed to .04-.08 in. (1-2 mm.) per year, and in 1993 accelerated to approximately .12 in. (3 mm.) per year (although it is not yet clear if this is a cyclical variance or part of an overall trend). Were these rates to hold steady, this would correspond to a rise of 11-13 in. (280-340 mm.) by 2100. However, some climate models, particularly those who look at the partial or complete melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet, indicate a more dramatic rise of about 3 ft. (1 m.), a rise that would, among other things, swamp most of the cities along the United States’ densely populated eastern seaboard.

Natural flooding is an important to the ecosystem, but is threatened by dams, levees, impoundments, and flood gates.

Rising water levels put the 634 million people who live within 30 ft. (9 m.) of sea level at risk for higher storm surges, coastal erosion, loss of agricultural and aquacultural land, loss of tourism, and a decline in soil and groundwater quality. Several small islands in the Pacific and Indian oceans, most notably the island nation of Tuvalu and the Maldives, are already seeing anomalous flooding and higher tides. Residents of these islands may be the first in a long line of "climate refugees" to come.

Climate change and flooding

Inland flooding will also be impacted by climate change. Rainfall patterns are expected to change over the next century, with climate models predicting more heavy-rain events, separated by prolonged periods of dry weather. Much of this will be due to the heating of the atmosphere: warmer air holds more water, raising the potential for a quick release of a large volume of water.

Air pollution will also play a role, as more particu-lates in the atmosphere gives this increased amount of water vapor more condensation nuclei, or seeds, around which they can coalesce. This will increase the incidence of flash flooding and landslides in many areas. So-called "100-year flood plains," literally parts of a flood plain that are only expected to flood once in a century, could expect to see flooding three to six times in a century.

Developing countries will see increased risk of loss of life in severe flood events. In summer 2007, the most intense floods seen in generations hit more than 20 African nations. Over 1.5 million people were displaced and at least 300 killed. Coming at the height of the growing season, the flooding destroyed domestic and export crops, and will exacerbate the region’s already severe food insecurity crisis. Meanwhile, more developed nations are planning extensive and costly new flood control systems and sea defenses to help mitigate future flooding.