Introduction

Child abuse is a generic term which embraces a wide range of behavior engaged in by those in a position of trust with regard to a child. Such abuse may be perpetrated within or outside the family setting and the types of abuse the child is subject to overlap (Table 1). Child abuse has been present throughout history in all cultures, but although often ignored in the past, it has been increasingly recognized as a problem in recent years.

Table 1 Types of abuse

Physical (nonaccidental injury)

Sexual

Emotional

Neglect

The Role of the Physician or Child Care Professional

Everyone involved in the care of children has a responsibility to recognize the possibility of abuse and to recognize the primacy of the welfare of the child. Assessment and investigation of suspected abuse is a multidisciplinary task, involving welfare agencies, health professionals and the criminal and civil justice systems.

Recording the Findings

Health professionals have a duty to recognize the possibility of abuse and to document carefully all their findings. There is no substitute for detailed, accurate contemporaneous notes, which should include the initial complaint and any explanation given by the child or its carers verbatim.

An accurate description of any injury must be recorded, including details of its nature, size, position and age, using diagrams and photographs where possible. Where the child presents soon after the injury has been sustained consideration should be given as to whether the collection of samples for forensic examination would be useful, remembering that ‘every contact leaves a trace’ (Locard’s principle).

In the preparation of reports for the courts and statutory authorities, it is of paramount importance that the health professional keeps an open mind and assesses any evidence objectively, considering all possible alternative explanations. A careful path must be trodden between over-interpreting the evidence on the one hand and failing to act decisively on the other where a child may be at risk. The emotional involvement of the professionals concerned has sometimes led to a lack of judgment and objectivity resulting in both over- and under-diagnosis of abuse.

Abuse usually escalates slowly over a long period of time, rather than being a single isolated event. However, a young or inadequate parent or carer may, in a fit of temper or frustration with an awkward, ill or disadvantaged child, lash out and cause serious injury, such as a skull fracture, shaking injury to the child or rupture to an internal abdominal organ, without really meaning to harm the child. At the other end of the spectrum sadistic abuse of the adult’s power over a child is, unfortunately, not rare.

Often abuse is not recognized at the time of first injury, either because the child cannot or will not tell, or because carers and professionals do not consider the possibility of abuse. It is important to realize that there may have been previous injuries or even the death of a child or siblings whose abusive cause has not been recognized.

Physical Abuse

Nonaccidental injury (NAI) may range in its presentation from a few bruises and scratches to a dead child. The initial presentation (Table 2) may be to any agency involved with that particular child. It is important, therefore, that there is training and support in the recognition of possible abuse for those agencies. Factors which should alert the professional include a delay in seeking treatment, inadequate or discrepant explanations for the injury, the presence of injuries of different ages, a history of previous injuries, failure to thrive and a carer showing little or no anxiety about the child’s condition.

Differential diagnosis

It is important to exclude other possible diagnoses, e.g. blood disorders or bone abnormalities, by taking a full medical history and completing a thorough examination. Every injury or pattern of injury should be evaluated so that the clinician can decide whether accidental or nonaccidental injury, carelessness, neglect or failure to cope, a traditional cultural practice or a medical condition offers the most satisfactory explanation for the clinical findings. The developmental stage of the child must be considered. A baby is not independently mobile and a clear explanation is required for any bruise or injury. However, it is important to recognize that bizarre accidents sometimes do happen and that they may not always be witnessed. Truth can sometimes be stranger than fiction.

The pattern of injury (Table 3) may be very helpful in determining causation and health care professionals should familiarize themselves with the typical patterns of fingertip and grip mark bruises, pinch marks and imprint abrasions and bruises left when a child is hit with an object, e.g. a belt, cord or stick. They should also be able to recognize innocent lesions which may mimic trauma, such as the Mongolian spot, juvenile striae or stretch marks and the marks left by coin rubbing (a traditional practice in some cultures). The aging of injuries is also very important but may be fraught with difficulty, especially with regard to the dating of bruising.

Table 2 Presentation

• Delay in seeking treatment

• Inadequate or changing explanation

• Lack of any explanation

• Injuries of different ages

• History of previous injury

• Failure to thrive

• Parent shows little concern

• Frozen awareness in child

Table 3 Common patterns of injury

• Any bruising on a baby

• Multiple bruises

• Pattern bruises

• Finger marks/hand weals

• Bilateral black eyes

• Torn upper frenulum

• Bite marks

• Cigarette burns

• Scalds and burns

• Fractures and head injury

Deliberately inflicted injury may be such that fracture of the bones occurs. It is for this reason that a full skeletal survey is frequently indicated (Table 4) when physical abuse is suspected, especially in the very young child. The interpretation of skeletal injuries in suspected child abuse must be approached with great caution and the advice of a senior radiologist with expertise in the field of child abuse sought.

The head is the commonest target for assault in the young child and head injury is the major cause of death after physical abuse. Most (95%) serious intracranial injury in the first year of life is the consequence of NAI. Such injury occurs in one of two ways: either, as a result of direct impact trauma, such as punching to the head or throwing or swinging the child so that the head comes into contact with a hard object; or, as a result of diffuse brain injury due to the acceleration-deceleration of shaking. This latter type of injury is usually associated with retinal hemorrhages.

Skull fractures sustained in accidental circumstances are typically single, narrow, hairline fractures, involving one bone only, usually the parietal, and are not often associated with intracranial injury. Depressed fractures can occur but are localized with a clear history of a fall onto a projecting object. In contrast, skull fractures which arise following NAI are typically multiple, complex and branched. The fractures are wide and often grow. Occipital fractures are highly specific for abuse but bilateral fractures occur, and often more than one bone is involved. A depressed fracture may occur singly as part of a complex fracture or there may be multiple, extensive such areas. Severe associated intracranial injury is common.

Table 4 Indications for skeletal survey

1. The history, type or pattern of injury suggests physical abuse.

2. Older children with severe bruising.

3. All children under 2 years of age where nonaccidental injury is suspected.

4. When a history of skeletal injury is present.

5. In children dying in suspicious or unusual circumstances.

Rib fractures are usually occult and detected only on X-ray or by radionuclide bone scanning. They are seen most commonly in infants and young children. In infants, in the absence of bone disease, the extreme pliability of the ribs implies that such fractures only occur after the application of considerable force.

Epiphyseal and metaphyseal fractures are injuries typical of NAI. The pulling and twisting forces applied to the limbs and body of a small child when it is shaken lead to disruption of the anatomy of the shafts of the long bones, subsequent periosteal reaction and ultimately new bone formation. Near the joints small chips of bone or the entire growth plate (corner and bucket handle fractures) may become separated from the shaft of the bone. Several different types of fracture of different ages and in different sites may be present in the same child.

Burns and scalds are also commonly seen in physical abuse. Again it is important to ascertain whether the explanation for the injury is consistent with the pattern of injury actually observed. The sharply demarcated area of tissue damage to the buttocks in the child who has been held in very hot water, for example, is quite different from the relatively haphazard pattern of injury in a child who has accidentally fallen into a container of hot water or tipped it over themselves.

Cigarette burns typically form a circular or oval cratered lesion 0.6-1.0 cm across which heals with scarring because it involves the full thickness of the skin. Causing such an injury is a sadistic act which involves the burning end of the cigarette being held in contact with the skin for 2-3 s. Accidentally dropping a cigarette on to a child or the child brushing against a lighted cigarette will cause only a very slight superficial burn.

Munchausen’s syndrome by proxy is a condition in which a carer, usually the mother, deliberately invents stories of illness in her child and then seeks to support this by causing appropriate physical symptoms. This often leads to the child being subjected to many unnecessary often invasive investigations and may involve the mother deliberately harming her child, for example by administering poisons or salt or by smothering the child. Sometimes such actions may lead to the death of the child.

Sudden infant death syndrome is the term applied to infants who die without their cause of death being ascertained. Many explanations for this phenomenon have been put forward, including, controversially that a small number of these deaths may in fact be undetected deliberately inflicted asphyxia.

Child Sexual Abuse

Child sexual abuse is any use of children for the sexual gratification of adults.

This may occur both inside and outside the family setting but always involves a betrayal of the child’s trust by the adult and an abuse of power. It encompasses a very wide range of behavior on the part of the adult, much of which will have a psychological effect on the child but may not leave any discernible physical evidence. Medical evidence, if present, is often equivocal, and forensic evidence, such as semen, is a rare finding, particularly in view of the fact that such abuse does not usually present to professionals acutely.

The child who may have been sexually abused may present in a number of ways. A spontaneous allegation by a child must always be taken very seriously. However, recent work has confirmed the child witness’s vulnerability to suggestion, a vulnerability which may lead to honest mistakes on the part of the child and also leave them open to exploitation by adults with their own agendas. Some children may present with sexualized behavior or with nonspecific signs of emotional disturbance or disturbed behavior. The child may be living in an environment where the risk of sexual abuse is thought to be high or there may be medical findings suggestive of sexual abuse.

The medical examination for child sexual abuse

It is important that the clinician is clear as to why examination of the child’s genitalia is necessary (Table 5). In every case it is good practice to seek formal written consent to examination from the adult who has parental responsibility for the child as well as explaining to the child themselves what is happening and why. Where a child withdraws consent for any part of the examination this withdrawal should be acknowledged and respected by the examining clinician. Loss of control over what is done to them is an important feature in abuse and this should not be compounded by the medical or forensic process.

Table 5 Reasons for medical examination

| Forensic | Therapeutic |

| • Establish cause of | • Diagnose and treat injuries |

| injuries | |

| • Take valid specimens: | • Check for medical causes |

| semen | • Sexually transmitted diseases |

| saliva | • Pregnancy |

| fibers | • Reassurance |

| Start recovery |

In suspected child sexual abuse the genitalia should be examined: to detect injuries, infection or disease which may need treatment; to reassure the child (and the carers) who may often feel that serious damage has been done; and, hopefully to start the process of recovery. In addition to these therapeutic reasons there are medicolegal reasons why examination is important: to help evaluate the nature of the abuse, and possibly to provide forensic evidence. It is important that the child is not abused by the process of examination itself and this should be well planned and kept to a minimum. A single examination whether carried out by one clinician alone or as a joint examination with a colleague is ideal and must be sensitive to the needs of the child.

The external genitalia should be carefully inspected to assess genital development and for any evidence of abnormality or injury. It is important that skin disease, such as lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, or infection, is recognized and that any changes produced are recognized as such and not mistakenly attributed to trauma.

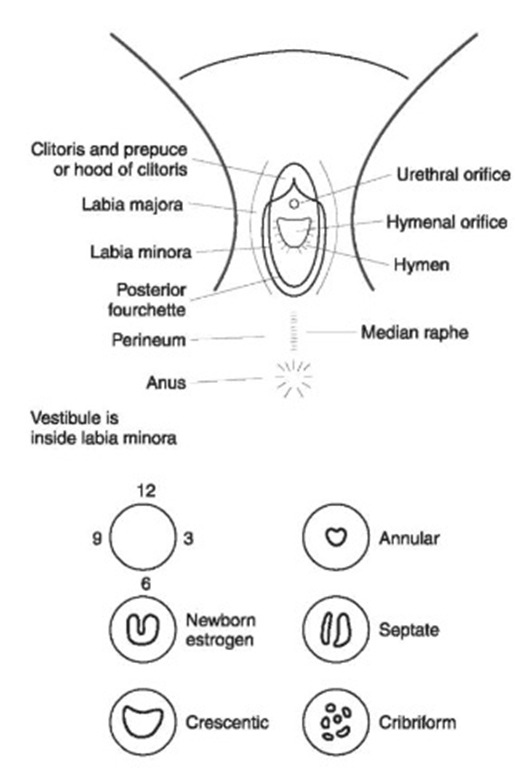

The hymen should be carefully examined, looking for notches, bumps and healed tears. Typically blunt force penetrating trauma, such as penile penetration, causes a full width tear of the hymen which may extend posteriorly into the fourchette. The quality of the edge of the hymen is important, as is the presence or absence of attenuation (loss of tissue). The size of the hymenal opening should be assessed although unless this is grossly enlarged (more than 1.5 cm diameter in the prepubertal child), its significance is debatable.

Where an abnormality of the hymen is suspected it is important that this is shown to be real and not due to examining position or poor technique. This can be established by demonstrating persistence of the feature by examining the child in more than one position, e.g. supine frog leg and knee chest, or using a technique to display the edge of the hymen, e.g. using a moistened swab or glass rod.

Interpreting the medical findings

At the end of the assessment the examining clinician should ask himself/herself whether the findings are normal or abnormal, and, if the latter, why? What has caused the abnormality? Is it abuse or not? Could the explanation be one of congenital anatomical variation, disease, accidental trauma or nonpenetrative or penetrative deliberately inflicted trauma. The clinician should carefully consider what weight should be attached to any findings, for example are they nonspecific, supportive but not diagnostic, or diagnostic of blunt force penetrating trauma, such as digital or penile penetration, through the hymen.

Positive medical findings are only present in a minority of cases. This is because much sexual abuse is of a type which does not lead to physical damage and victims often do not come to attention before any minor injuries have healed. Also there is a wide range of normal anatomical variation in the structures in the genital and anal region and studies have shown that many of the findings thought to be suggestive of sexual abuse are in fact present in the nonabused population. It is important, therefore, that the examining clinician is familiar with normal anatomy (Fig. 1) and the changes which take place in its appearance with age (from infancy through the prepubertal years to puberty), is able to describe any findings accurately using a standard nomenclature, and, where possible, record the findings photographically so as to allow peer review of the findings.

Figure 1 The prepubertal vulva.

Intercrural intercourse (pushing the penis between the thighs against the genitalia with little or no actual penetration) usually does not result in any injury although occasionally there may be bruising to the perineum. Nonspecific findings such as patchy redness of the labia and perineum are common. Splits to the fourchette do occur and may sometimes heal with scarring. Pressure by the penis on the outer genitalia is perceived as painful by the child who may be honestly mistaken as to whether penetration has taken place or not.

Accidental trauma, such as straddle injury, usually causes injury to the vulva, fourchette or vestibule. Such injuries are commonly anterior, unilateral and consist of bruising of the labia, often with a deep bruise or even a split in the cleft between the labia major a and minor a or between the labia minora and the clitoris. The hymen is an internal structure protected by the vulva and will only be damaged if there is a penetrative component to the injury.

Anal findings

The significance of anal findings or their absence has been a much debated subject. Most, such as bruising, abrasion, fissures, ‘reflex’ anal dilatation and anal laxity, can be caused by penetrative abuse or may have an innocent explanation. Where lubrication has been used there may be no positive clinical findings even when a child is examined within hours of penile anal penetration having occurred. The only diagnostic finding is semen in the anal canal or rectum and this is rare.

Fissures occur when the anal tissues are dilated beyond their elastic limit. They should be carefully distinguished from prominent folds in the anal canal. They may be multiple or single. They are acutely painful at the time of their formation and there is usually some associated bleeding which can vary from the trivial to the torrential. However, other causes of bleeding should be sought. Fissures, especially if they become chronic, may heal with scarring and the formation of skin tags.

The skin of the anal verge may be swollen after recent abuse or may become thickened, rounded and smooth after repeated abuse but such changes are not sufficient in themselves to lead to suspicions of abuse.

Provided that the bowel is normal and that there is no neurological disorder, abnormal anal sphincter tone implies that something hard and bulky has passed through the sphincter, but does not distinguish the direction of movement, from inside out or vice versa. Any history of medical investigation, treatment or bowel problems is, therefore, likely to be of significance and should be actively sought, both from the child and the carer.

The internal anal sphincter maintains anal closure and continence. Stretching or tearing of the muscle fibers may lead to incompetence of the sphincter and to anal soiling. The presence of feces in the lower rectum may also lead to physiological relaxation of the sphincter.

‘Reflex’ anal dilatation is not a reflex at all, but refers to the opening of the anal sphincter some 10 s after gentle buttock separation has been applied. It may be present in both abused and nonabused children and in the presence of feces in the rectum. Its significance is unproven and although it may raise the suspicion of abuse it is not a reliable sole diagnostic sign.

Forensic evidence

When children present acutely after suspected sexual abuse, consideration should always be given to the collection of forensic samples both for biological (saliva, semen, hairs etc.) and nonbiological trace evidence (fibers).

Where children have been subjected to sexual abuse by strangers then tests for sexually transmitted diseases should always be considered, discussed with the carers and taken where possible. In intrafamilial cases it is desirable to take tests from the child but, especially where this may cause distress, asking other members of the family, such as the suspected perpetrator, to attend the genitourinary clinic may be helpful. Where infection is present it is desirable to seek the opinion of a specialist in genitourinary medicine with regard to treatment and the medicolegal significance of that particular infection. This involves assessing such factors as the age of the child, the prevalence of the disease in the community, its presence or absence in the alleged perpetrator, its incubation period and possible modes of transmission.

Genital warts in a child can be transmitted by sexual contact and should raise a suspicion of sexual abuse. However, warts have a long incubation period and transmission during the birth process and from the mother or carer during toileting procedures should be considered. Self-inoculation or transmission from innocent skin contact may lead to genital or anal wart infection with the common wart virus.

In postpubertal girls the possible need for post-coital contraception or a pregnancy test must be addressed.

Emotional Abuse and Neglect

Emotional abuse and neglect of children may take many forms, including failure to meet physical needs, a failure to provide consistent love and nurture through to overt hostility and rejection. It is rare for other forms of abuse to have occurred without some element of emotional abuse at least.

The deleterious effects on children are manifold and are very much age dependent as to how they present. In the infant the presentation is usually with failure to thrive, recurrent and persistent minor infections, frequent attendances at the Accident and Emergency Department or admissions to hospital, severe nappy rash or unexplained bruising. There is often general developmental delay and a lack of social responsiveness. These signs and symptoms may have alternative innocent organic explanations and these must always be excluded.

A preschool child who has suffered emotional abuse and neglect will often present as dirty and unkempt and of short stature. Socioemotional immaturity, language delay which may be profound, and a limited attention span may also be displayed. This may be associated with aggressive, impulsive and often over-active behavior which may lead to increasing hostility and rejection from their carers. However, behavior with strangers is in direct contrast to this as the child may be indiscriminately friendly, constantly seeking physical contact (‘touch hunger’) and reassurance.

In the school age child, persistent denigration and rejection leads to very low self-esteem, coupled with guilt as the child feels responsible for the way things are and self-blame is common. This leads to a child with few or dysfunctional relationships who may exhibit self-stimulating behavior or self-harm. Disturbances in the pattern of urination or defecation are common. Sometimes behavior may be bizarre and extreme. Physically the child may be of short stature, be unkempt and have poor personal hygiene. Learning difficulties, poor coping skills and immaturity of social and emotional skills may also be exhibited.

In the adolescent, although emotional abuse and neglect is less often reported, it is common and may start at this age especially in girls. It can have a profound effect on adolescent adjustment and usually results in a whole range of self-harm and behavioral problems both contemporaneously and into early adult life. These include sexual promiscuity, early pregnancy, running away, suicide attempts, self-harm, drug and alcohol abuse, and delinquent behavior. Intervention in this age group is fraught with difficulty and is often the most neglected, reinforcing the adolescent’s perception of rejection and low self-esteem.

Where failure to thrive and short stature are an issue, it is important that organic causes are excluded and corrected before this is presumed to be due to emotional abuse and neglect. There is no substitute for regular and accurate height and weight measurements which should be taken and plotted on the appropriate centile chart whenever a child presents with a possible diagnosis of child abuse. Where abuse is a factor, such charts will show a characteristic catch up growth when the child is removed from the source of abuse. Disordered patterns of eating and behavior relating to food will often resolve at this time also.

In conclusion, adults can behave in a wide variety of ways which result in the abuse of their power over children. Such abuse may have emotional, behavioral and physical consequences which in extreme cases may lead to the death of a child. Working with survivors of all types of abuse to minimize its effect on their lives and enable such children to fulfill their potential is a task which must be shared by professionals and society at large. Only then can the inter-generational cycle of abuse and deprivation be broken. The role of the forensic clinician is to bring together professional skills and knowledge about the nature of injuries, the possible mechanisms of their causation, patterns of healing and variations in appearance with time, and an awareness of appropriate forensic investigations, such as the careful gathering of samples of body fluids, trace evidence and radiographs. With the welfare of the child as the prime concern, and treating all the parties involved with consideration and respect at all times, the clinician must use these skills to work as part of a multi-disciplinary team in the interests of the child.