Traders will often maintain a long-term position in a futures market by holding a contract until near to its maturity, closing out the position and establishing a new position of similar size in a contract with a longer maturity. This is known as rolling a position forward. In following such a strategy the trader faces certain risks which would not arise if he had maintained a position in a single long-dated futures contract.

In particular the strategy is affected by the difference between the price at which the old contract is terminated and the new contract is entered into. The price difference between futures contracts on the same underlying asset but with different maturities is known as a calendar spread. The spread is predictable if the futures contracts are trading at their theoretical fair value. However, futures contracts often trade at a premium or discount to fair value, and this gives rise to rollover risk.

Suppose, for example, that the trader wants to be long on a futures contract. If the futures contract which he holds is trading at a discount to fair value and the contract which he wants to roll into is trading at a premium, then the trader will make a loss on rolling over. He is selling cheap and buying dear. Clearly, the position could well be the other way round, in which case the trader would make a rollover gain.

In principle, the trader could avoid rollover risk by entering into a futures contract whose maturity extends at least as far as the horizon over which the trader wants to maintain the position. In practice, there are a number of reasons why the trader may not wish to do this. First, there may not exist any traded futures contracts with a sufficiently long maturity. Second, the longer-dated contracts which are traded may be illiquid. In most futures markets much of the liquidity is in the contracts closest to maturity. The bid-ask spread tends to be narrower, and it is generally possible to deal in larger size in short-dated contracts. Third, rollover risk represents an opportunity as we ll as a danger. If the trader can forecast the behavior of the calendar spread, the strategy o f rolling from contract to contract may have a lower expected cost than a strategy of maintaining a position in a single long-dated contract.

Rollover Risk in the Commodities Market

The issue of rollover risk has come into particular prominence since the substantial losses incurred by the German company Metallgesellschaft and its US oil refining and marketing subsidiary MGRM. In brief, MGRM sold oil forward on long-term fixed price contracts and hedged itself by buying short-dated oil futures, and similar over the counter products, which it rolled forward. As the oil price fell it was required to fund its futures position; eventually the position was closed out in 1994 with MGRM incurring substantial losses (see Culp and Miller, 1995).

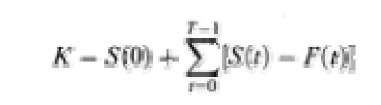

The nature of the risks taken by MGRM can be understood by considering a very simple world with zero interest rates where an agent at time 0 writes a forward contract to deliver one barrel of oil in T months time at a price of US$X/barrel. The agent hedges himself by buying one-month futures and holding them to maturity, rolling forward monthly. At time T he buys the oil on the spot market and deliver s it to the client. Assume that each month the futures contract final settlement price is equal t o the spot price, the agent’s profit on the whole strategy is:

where S(t) is the spot price of oil at time t and F(t) is the futures price at time t for a futures contract with one month to maturity.

This equation shows that the profit can be decomposed into two parts. The first is the difference between the contract price and the spot price, both of which are fixed at the outset. The second is related to the difference between the spot price and the contemporaneous futures price over the life of the contract.

Historically the oil market has tended to be in backwardation. The near-term future has tended to trade above the longer maturity future for much of the last decade. So the second term in the equation has generally been positiv e. There has been much discussion about why this has occurred and whether it can be expected to persist (see Litzenberger and Rabinowitz, 1995).

Spot and futures prices are tied together by arbitrage trades. The cash and carry relation means that the future price should equal the spot price less the yield from holding the asset (the convenience yield less any storage costs) plus the cost of financing. If the spot is high relative to the futures, agents who have surplus oil will earn high returns by selling the oil spot and buying it forward. Conversely if the spot is low the arbitrage trade involves buying the spot, storing it and selling it forward.

The relationship is not very tight. The costs of performing the transaction may be quite substantial. Furthermore, neither the convenience yield nor the cost of storage is constant; they will tend to vary substantially with the level of inventory. If there are large inventories the marginal storage cost will be high, the marginal convenience yield will be low and the future may trade at a premium (contango) with out permitting arbitrage. When inventories are low, the converse may hold, and the future will trade at a discount (backwardation).

The significance of rollover risk in a long-term hedging strategy depends on the stability of the term structure of oil futures prices. Culp and Miller (1995) and Mello and Parsons (1995) offer conflicting views of this in the specific context of the Metallgesellschaft case.

Rollover Risk in the Financial Markets

Rollover risk tends to be smaller with financial futures than with commodity futures. Storage costs for the underlying asset (a bond, or a portfolio of shares) are much lower and more predictable than for commodities. The yield from owning the underlying asset is the coupon or dividend on the financial asset which can normally be predicted rather precisely, at least in the short term.

Nevertheless the arbitrage between the future and the spot asset is neither costless nor riskless. This means that financial futures do not trade exactly at their theoretical value. To the extent that the difference between the two is hard to predict, rollover risk is a problem for the trader who is rolling over financial futures contracts just as it is for commodity futures.