42. Additions to Net Working Capital

A component of the cash flow of the firm, along with operating cash flow and capital spending. These cash flows are used for making investments in net working capital.

Total cash flow of the firm = Operating cash flow — Capital spending — Additions to net working capital.

43. Add-on Interest

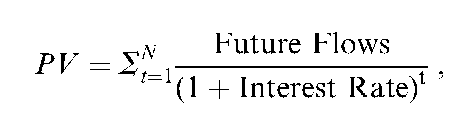

Add-on interest means that the total interest owed on the loan, based on the annual stated interest rate, is added to the initial principal balance before determining the periodic payment. This kind of loan is called an add-on loan. Payments are determined by dividing the total of the principal plus interest by the number of payments to be made. When a borrower repays a loan in a single, lump sum, this method gives a rate identical to annual stated interest. However, when two or more payments are to be made, this method results in an effective rate of interest that is greater than the nominal rate. Putting this into equation form, we see that:

where PV = the present value or loan amount; t = the time period when the interest and principal repayment occur; and N = the number of periods.

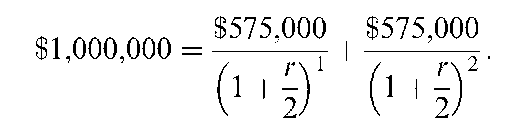

For example, if a million-dollar loan were repaid in two six-month installments of $575,000 each, the effective rate would be higher than 15 percent, since the borrower does not have the use of the funds for the entire year. Allowing r to equal the annual percentage rate of the loan, we obtain the following:

Using a financial calculator, we see that r equals 19.692 percent, which is also annual percentage return (APR). Using this information, we can obtain the installment loan amortization schedule as presented in the following table.

| Beginning | Interest (0.19692)/ | Principal | Ending Loan | |

| Payment | Balance | 2 X (b) | Paid | Balance |

| (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | (e) |

| Period | (a) – (c) | (b) – (d) | ||

| 1 $575,000 | $1,000,000 | $98.460 | $476,540 | $523,460 |

| 2 575,000 | 523,460 | 51,540 | 523,460 | 0 |

| Biannual payment: | $575,000 | |||

| Initial balance: | $1,000,000 | |||

| Initial maturity: | One year | |||

| APR: | 19.692% |

44. Add-OnRate

A method of calculating interest charges by applying the quoted rate to the entire amount advanced to a borrower times the number of financing periods. For example, an 8 percent add-on rate indicates $80 interest per $1,000 for 1 year, $160 for 2 years, and so forth. The effective interest rate is higher than the add-on rate because the borrower makes installment payments and cannot use the entire loan proceeds for full maturity. [See also Add-on interest]

45. Adjustable-Rate Mortgage (ARM)

A mortgage whose interest rate varies according to some specified measure of the current market interest rate. The adjustable-rate contract shifts much of the risk of fluctuations in interest rates from the lender to the borrower.

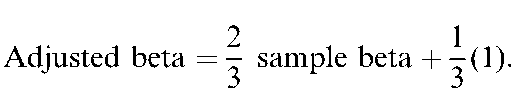

46. Adjusted Beta

The sample beta estimated by market model can be modified by using cross-sectional market information [see Vasicek, 1973]. This kind of modified beta is called adjusted beta. Merrill Lynch’s adjusted beta is defined as:

47. Adjusted Forecast

A (micro or macro) forecast that has been adjusted for the imprecision of the forecast. When we forecast GDP or interest rate over time, we need to adjust for the imprecision of the forecast of either GDP or interest rate.

48. Adjusted Present Value (APV) Model

Adjusted present value model for capital budgeting decision. This is one of the methods used to do capital budgeting for a levered firm. This method takes into account the tax shield value associated with tax deduction for interest expense. The formula can be written as:

APV = NPV + TCD,

where APV = Adjusted present value; NPV = Net present value; Tc = Marginal corporate tax rate;

D = Total corporate debt; and TcD = Tax shield value.

This method is based upon M&M Proposition I with tax. [See also Modigliani and Miller (M&M) Proposition I]

49. ADR

American Depository Receipt: A certificate issued by a US bank which evidences ownership in foreign shares of stock held by the bank.

50. Advance

A payment to a borrower under a loan agreement.

51. Advance Commitment

This is one of the methods for hedging interest rate risk in a real estate transaction. It is a promise to sell an asset before the seller has lined up purchase of the asset. This seller can offset risk by purchasing a futures contract to fix the sale price. We call this a long hedge by a mortgage banker because the mortgage banker offsets risk in the cash market by buying a futures contract.

52. Affiliate

Any organization that is owned or controlled by a bank or bank holding company, the stockholders, or executive officers.

53. Affinity Card

A credit card that is offered to all individuals who are part of a common group or who share a common bond.

54. After-Acquired Clause

A first mortgage indenture may include an after-acquired clause. Such a provision states that any property purchased after the bond issue is considered to be security for the bondholders’ claim against the firm. Such a clause also often states that only a certain percentage of the new property can be debt financed.

55. Aftermarket

The period of time following the initial sale of securities to the public; this may last from several days to several months.

56. After-Tax Real Return

The after-tax rate of return on an asset minus the rate of inflation.

57. After-Tax Salvage Value

After-tax salvage value can be defined as:

After-tax salvage value = Price — T(Price — BV),

where Price = market value; T= corporate tax rate; and BV= book value.

If T(Price – BV) is positive, the firm owes taxes, reducing the after-tax proceeds of the asset sale; if T(Price – BV) is negative, the firm reduces its tax bill, in essence increasing the after-tax proceeds of the sale. When T(Price – BV) is zero, no tax adjustment is necessary.

By their nature, after-tax salvage values are difficult to estimate as both the salvage value and the expected future tax rate are uncertain.

As a practical matter, if the project termination is many years in the future, the present value of the salvage proceeds will be small and inconsequential to the analysis. If necessary, however, analysts can try to develop salvage value forecasts in two ways. First, they can tap the expertise of those involved in secondary market uses of the asset. Second, they can try to forecast future scrap material prices for the asset. Typically, the after-tax salvage value cash flow is calculated using the firm’s current tax rate as an estimate for the future tax rate.

The problem of estimating values in the distant future becomes worse when the project involves a major strategic investment that the firm expects to maintain over a long period of time. In such a situation, the firm may estimate annual cash flows for a number of years and then attempt to estimate the project’s value as a going concern at the end of this time horizon. One method the firm can use to estimate the project’s going-concern value is the constant dividend growth model.

58. Agency Bond

Bonds issued by federal agencies such as Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA) and government/government-sponsored enterprises such as Small Business Administration (SBA). An Agency bond is a direct obligation of the Treasury even though some agencies are government sponsored or guaranteed. The net effect is that agency bonds are considered almost default-risk free (if not legally so in all cases) and, therefore, are typically priced to provide only a slightly higher yield than their corresponding T-bond counterparts.

59. Agency Costs

The principal-agent problem imposes agency costs on shareholders. Agency costs are the tangible and intangible expenses borne by shareholders because of the self-serving actions of managers. Agency costs can be explicit, out-of-pocket expenses (sometimes called direct agency costs) or more implicit ones (sometimes called implicit agency costs). [See also Principal-agent problem]

Examples of explicit agency costs include the costs of auditing financial statements to verify their accuracy, the purchase of liability insurance for board members and top managers, and the monitoring of managers’ actions by the board or by independent consultants.

Implicit agency costs include restrictions placed against managerial actions (e.g., the requirement of shareholder votes for some major decisions) and covenants or restrictions placed on the firm by a lender.

The end result of self-serving behaviors by management and shareholder attempts to limit them is a reduction in firm value. Investors will not pay as much for the firm’s stock because they realize that the principal-agent problem and its attendant costs lower the firm’s value.

Conflicts of interest among stockholders, bondholders, and managers will rise. Agency costs are the costs of resolving these conflicts. They include the costs of providing managers with an incentive to maximize shareholder wealth and then monitoring their behavior, and the cost of protecting bondholders from shareholders. Agency costs will decline, and firm value will rise, as principals’ trust and confidence in their agents rise. Agency costs are borne by stockholders.

60. Agency Costs, Across National Borders

Agency costs may differ across national borders as a result of different accounting principles, banking structures, and securities laws and regulations. Firms in the US and the UK use relatively more equity financing than firms in France, Germany and Japan. Some argue that these apparent differences can be explained by differences in equity and debt agency costs across the countries.

For example, agency costs of equity seem to be lower in the US and the UK. These countries have more accurate systems of accounting (in that the income statements and balance sheets are higher quality reflecting actual revenues and expenses, assets and liabilities) than the other countries, and have higher auditing standards. Dividends and financial statements are distributed to shareholders more frequently, as well, which allows shareholders to monitor management more easily.

Germany, France, and Japan, on the other hand, all have systems of debt finance that may reduce the agency costs of lending. In other countries, a bank can hold an equity stake in a corporation, meet the bulk of the corporation’s borrowing needs, and have representation on the corporate board of directors. Corporations can own stock in other companies and also have representatives on other companies’ boards. Companies frequently get financial advice from groups of banks and other large corporations with whom they have interlocking directorates. These institutional arrangements greatly reduce the monitoring and agency costs of debt; thus, debt ratios are substantially higher in France, Germany, and Japan.

61. Agency Problem

Conflicts of interest among stockholders, bondholders, and managers.

62. Agency Securities

Fixed-income securities issued by agencies owned or sponsored by the federal government. The most common securities are issued by the Federal Home Loan Bank, Federal National Mortgage Association, and Farm Credit System.

63. Agency Theory

The theory of the relationship between principals and agents. It involves the nature of the costs of resolving conflicts of interest between principals and agents.

64. Agents

Agents are representatives of insurers. There are two systems used to distribute or sell insurance. The direct writer system involves an agent representing a single insurer, whereas the independent agent system involves an agent representing multiple insurers. An independent agent is responsible for running an agency and for the operating costs associated with it. Independent agents are compensated through commissions, but direct writers may receive either commissions or salaries.

65. Aggregation

This is a process in long-term financial planning. It refers to the smaller investment proposals of each of the firm’s operational units are added up and in effect treated as a big picture.

66. Aging Accounts Receivable

A procedure for analyzing a firm’s accounts receivable by dividing them into groups according to whether they are current or 30, 60, or over 90 days past due.

67. Aging Schedule of Accounts Receivable

A compilation of accounts receivable by the age of account.

Typically, this relationship is evaluated by using the average collection period ratio. This type of analysis can be extended by constructing an aging-of-accounts-receivable table. The following table shows an example of decline in the quality of accounts receivable from January to February as relatively more accounts have been outstanding for 61 days or longer. This breakdown allows analysis of the cross-sectional composition of accounts over time. A deeper analysis can assess the risk associated with specific accounts receivable, broken down by customer to associate the probability of payment with the dollar amount owed.

| January Accounts |

February Accounts |

|||

| Days | Receivable | Percent of | Receivable | Percent of |

| Outstanding | Range | Total | Range | Total |

| 0-30 days | $250,000 | 25.0% | $250,000 | 22.7% |

| 31-60 days | 500,000 | 50.0 | 525,000 | 47.7 |

| 61-90 days | 200,000 | 20.0 | 250,000 | 22.7 |

| Over 90 days | 50,000 | 5.0 | 75,000 | 6.8 |

| Total accounts receivable | $1,000,000 | 100.0% | $1,100,100 | 100.0% |

68. All-in-Cost

The weighted average cost of funds for a bank calculated by making adjustments for required reserves and deposit insurance costs, the sum of explicit and implicit costs.

69. Allocational Efficiency

The overall concept of allocational efficiency is one in which security prices are set in such a way that investment capital is directed to its optimal use. Because of the position of the US in the world economy, the allocational responsibility of the US markets can be categorized into international and domestic efficiency. Also, since the overall concept of allocational efficiency is too general to test, operational efficiency must be focused upon as a testable concept.

70. Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses

An accounting reserve set aside to equate expected (mean) losses from credit defaults. It is common to consider this reserve as the buffer for expected losses and some risk-based economic capital as the buffer for unexpected losses.

71. Alpha

The abnormal rate of return on a security in excess of what would be predicted by an equilibrium model like CAPM or APT. For CAPM, the alpha for the ith firm (ai) can be defined as:

a = (Ri – Rf) – bi(Rm – Rf),

where Ri = average return for the ith security, Rm = average market rate of return, Rf = risk-free rate, and bi = beta coefficient for the ith security.

Treynor and Black (1973) has used the alpha value to form active portfolio.

72. Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT)

A federal tax against income intended to ensure that taxpayers pay some tax even when they use tax shelters to shield income.

73. American Depository Receipt (ADR)

A security issued in the US to present shares of a foreign stock, enabling that stock to be traded in the US. For example, Taiwan Semiconductors (TSM) from Taiwan has sold ADRs in the US.

74. American Option

An American option is an option that can be exercised at any time up to the expiration date. The factors that determine the values of American and European options are the same except the time to exercise the option; all other things being equal, however, an American option is worth more than a European option because of the extra flexibility it grants the option holder.

75. Amortization

Repayment of a loan in installments. Long-term debt is typically repaid in regular amounts over the life of the debt. At the end of the amortization the entire indebtedness is said to be extinguished. Amortization is typically arranged by a sinking fund. Each year the corporation places money into a sinking fund, and the money is used to buy back the bond.

76. Amortization Schedule for a Fixed-Rate Mortgage

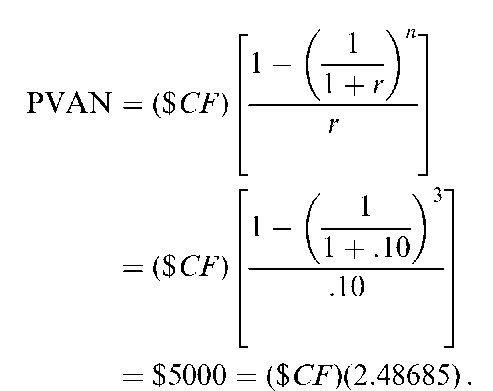

Amortization schedule for a fixed-rate mortgage is used to calculate either the monthly or the annual payment for a fixed rate mortgage.

The following example is used to show the procedure for calculating annual payment for a fixed-rate mortgage.

Suppose Bill and Debbie have taken out a home equity loan of $5,000, which they plan to repay over three years. The interest rate charged by the bank is 10 percent. For simplicity, assume that Bill and Debbie will make annual payments on their loan. (a) Determine the annual payments necessary to repay the loan. (b) Construct a loan amortization schedule.

(a) Finding the annual payment requires the use of the present value of an annuity relationship:

This result is an annual payment ($CF) of $5,000/ 2.48685 = $2,010.57.

(b) Below is the loan amortization schedule constructed for Bill and Debbie:

| Beginning | Annuity | Interest Paid | Principal Paid | Ending Balance | |

| Year | Balance | Payments | (2) x 0.10 | (3) – (4) | (2) – (5) |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

| 1 | $5,000.00 | $2,010.57 | $500.00 | $1,510.57 | $3,489.43 |

| 2 | 3,489.43 | 2,010.57 | 348.94 | 1,661.63 | 1,827.80 |

| 3 | 1,827.80 | 2,010.57 | 182.78 | 1,827.79 | 0.01 |

77. Amortize

To reduce a debt gradually by making equal periodic payments that cover interest and principal owed. In other words, it liquidates on an installment basis. [See also Amortization]

78. Amortizing Swap

An interest rate swap in which the outstanding notional principal amount declines over time. It generally is used to hedge interest rate risk or mortgage or other amortized loan.

79. Angels

Individuals providing venture capital. These investors do not belong to any venture-capital firm; these investors act as individuals when providing financing. However, they should not be viewed as isolated investors.

80. Announcement Date

Date on which particular news concerning a given company is announced to the public; used in event studies, which researchers use to evaluate the economic impact of events of interest. For example, an event study can be focused on a dividend announcement date.

81. Announcement Effect

The effect on stock returns for the first trading day following an event announcement. For example, an earnings announcement and a dividend announcement will affect the stock price.

82. Annual Effective Yield

Also called the effective annual rate (EAR). [See also Effective annual rate (EAR)]

83. Annual Percentage Rate (APR)

Banks, finance companies, and other lenders are required by law to disclose their borrowing interest rates to their customers. Such a rate is called a contract or stated rate, or more frequently, an annual percentage rate (APR). The method of calculating the APR on a loan is preset by law. The APR is the interest rate charged per period multiplied by the number of periods in a year:

APR = r x m,

where r = periodic interest charge, and m = number of periods per year.

However, the APR misstates the true interest rate. Since interest compounds, the APR formula will understate the true or effective interest cost. The effective annual rate (EAR), sometimes called the annual effective yield, adjusts the APR to take into account the effects of compounded interest over time. [See also Effective annual rate (EAR)]

It is useful to distinguish between a contractual or stated interest rate and the group of rates we call yields, effective rates, or market rate. A contract rate, such as the annual percentage rate (APR), is an expression that is used to specify interest cash flows such as those in loans, mortgages, or bank savings accounts. The yield or effective rate, such as the effective annual rate (EAR), measures the opportunity costs; it is the true measure of the return or cost of a financial instrument.

84. Annualized Holding-Period Return

The annual rate of return that when compounded T times, would have given the same T-period holding return as actual occurred from period 1 to period T. If Rt is the return in year t (expressed in decimals), then:

(1 + R1) x (1 + R2) x (1 + R3) x (1 + R4) is called a four-year holding period return.

85. Annuity

An annuity is a series of consecutive, equal cash flows over time. In a regular annuity, the cash flows are assumed to occur at the end of each time period. Examples of financial situations that involve equal cash flows include fixed interest payments on a bond and cash flows that may arise from insurance contracts, retirement plans, and amortized loans such as car loans and home mortgages.

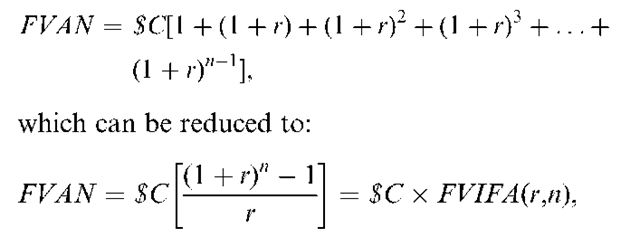

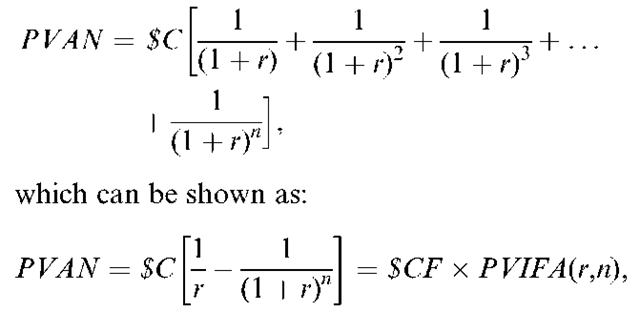

The future value of an n-period annuity of $C per period is

where FVIFA (r,n) represents the future value interest factor for an annuity.

To find the present value of an n-period annuity of $C per period is

where PVIFA(r,n) is the present value interest factor for an annuity.

86. Annuity Due

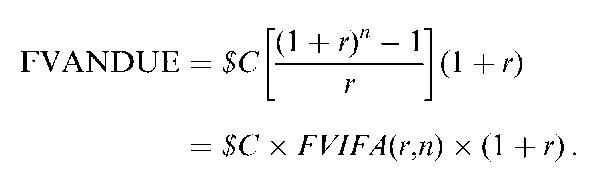

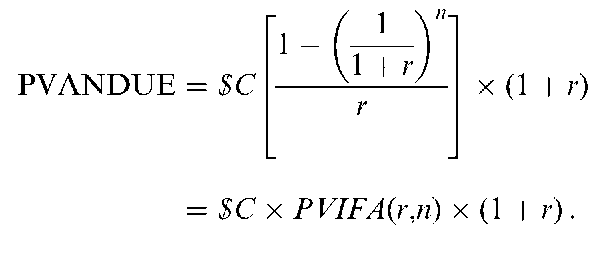

When a cash flow occurs at the beginning of each annuity period, the annuity becomes an annuity due. Since the cash flows in the n-year annuity due occurs at the beginning of each year, they are invested for one extra period of time compared to the n-year regular annuity. This means all the annuity due cash flows are invested at r percent interest for an extra year.

To take this one extra year of compounding into account, the future value interest factor for an annuity [FVIFA (r,n)] can be multiplied by (1 + r) to determine the future value interest factor for an annuity due (FVANDUE):

Many situations also require present value calculations for cash flows that occur at the beginning of each time period. Examples include retirement checks that arrive on the first of the month and insurance premiums that are due on the first of the month. Again, the cash flows for the n-year annuity due occur one year earlier than those of the n-year regular annuity, making them more valuable. As in determining the FVANDUE, we can adjust for this simply by multiplying the corresponding PVIFA by (1 + r) to reflect the fact that the cash flows are received one period sooner in an annuity due. The formula for the present value of an annuity due (PVANDUE) is

87. Annuity Factor

The term used to calculate the present value or future value of the stream of level payments for a fixed period. [See also Annuity]

88. Annuity in Advance

An annuity with an immediate initial payment. This is called annuity due. [See also Annuity due]

89. Annuity in Arrears

An annuity with a first payment one full period hence, rather than immediately. That is, the first payment occurs on date 1 rather than on date 0.

90. Anticipated Income Theory

A theory that the timing of loan payments should be tied to the timing of a borrower’s expected income.

91. Antithetic Variate Method

A technique used in Monte Carlo valuation, in which each random draw is used to create two simulated prices from opposite tails of the asset price distribution. This is one of the variance reduction procedures. Other method is stratified sampling method [See Stratified sampling]

92. Applied Research

A research and development (R&D) component that is riskier than development projects. [See also Development projects] It seeks to add to the firm’s knowledge base by applying new knowledge to commercial purposes.

93. Appraisal Ratio

The signal-to-noise ratio of an analyst’s forecasts. The ratio of alpha to residual standard deviation. This ratio measures abnormal return per unit of risk that in principle could be diversified away by holding a market index portfolio.

94. Appraisal Rights

Rights of shareholders of an acquired firm that allow them to demand that their shares be purchased at a fair value by the acquiring firm.

95. Appreciation

An increase in the market value of an asset. For example, you buy one share of IBM stock at $90. After one year you sell the stock for $100, then this investment appreciated by 11.11 percent.

96. Appropriation Phase of Capital Budgeting

The focus of the appropriation phase, sometimes called the development or selection phase, is to appraise the projects uncovered during the identification phase. After examining numerous firm and economic factors, the firm will develop estimates of expected cash flows for each project under examination. Once cash flows have been estimated, the firm can apply time value of money techniques to determine which projects will increase shareholder wealth the most.

The appropriation phase begins with information generation, which is probably the most difficult and costly part of the phase. Information generation develops three types of data: internal financial data, external economic and political data, and nonfinancial data. This data supports forecasts of firm-specific financial data, which are then used to estimate a project’s cash flows. Depending upon the size and scope of the project, a variety of data items may need to be gathered in the information generation stage. Many economic influences can directly impact the success of a project by affecting sales revenues, costs, exchange rates, and overall project cash flows. Regulatory trends and political environment factors, both in the domestic and foreign economies, also may help or hinder the success of proposed projects.

Financial data relevant to the project is developed from sources such as marketing research, production analysis, and economic analysis. Using the firm’s research resources and internal data, analysts estimate the cost of the investment, working capital needs, projected cash flows, and financing costs. If public information is available on competitors’ lines of business, this also needs to be incorporated into the analysis to help estimate potential cash flows and to determine the effects of the project on the competition.

Nonfinancial information relevant to the cash flow estimation process includes data on the various means that may be used to distribute products to consumers, the quality and quantity of the domestic or nondomestic labor forces, the dynamics of technological change in the targeted market, and information from a strategic analysis of competitors. Analysts should assess the strengths and weaknesses of competitors and how they will react if the firm undertakes its own project.

After identifying potentially wealth-enhancing projects, a written proposal, sometimes called a request for appropriation is developed and submitted to the manager with the authority to approve. In general, a typical request for appropriation requires an executive summary of the proposal, a detailed analysis of the project, and data to support the analysis.

The meat of the appropriation request lies in the detailed analysis. It usually includes sections dealing with the need for the project, the problem or opportunity that the project addresses, how the project fits with top management’s stated objectives and goals for the firm, and any impact the project may have on other operations of the firm.

The appropriation process concludes with a decision. Based upon the analysis, top management decides which projects appear most likely to enhance shareholder wealth. The decision criterion should incorporate the firm’s primary goal of maximizing shareholder wealth.

97. Arbitrage

Arbitrage is when traders buy and sell virtually identical assets in two different markets in order to profit from price differences between those markets.

Besides currencies, traders watch for price differences and arbitrage opportunities in a number of financial markets, including stock markets and futures and options markets. In the real world, this process is complicated by trading commissions, taxes on profits, and government restrictions on currency transfers. The vigorous activity in the foreign exchange markets and the number of traders actively seeking risk-free profits prevents arbitrage opportunities based on cross-rate mispricing from persisting for long.

In other words arbitrage refers to buying an asset in one market at a lower price and simultaneously selling an identical asset in another market at a higher price. This is done with no cost or risk.

98. Arbitrage Condition

Suppose there are two riskless assets offering rates of return r and r’, respectively. Assuming no transaction costs, one of the strongest statements that can be made in positive economics is that

![]()

This is based on the law of one price, which says that the same good cannot sell at different prices. In terms of securities, the law of one price says that securities with identical risks must have the same expected return. Essentially, equation (A) is a arbitrage condition that must be expected to hold in all but the most extreme circumstances. This is because if r > r’, the first riskless asset could be purchased with funds obtained from selling the second riskless asset. This arbitrage transaction would yield a return of r — r’ without having to make any new investment of funds or take on any additional risk. In the process of buying the first asset and selling the second, investors would bid up the former’s price and bid down the latter’s price. This repricing mechanism would continue up to the point where these two assets’ respective prices equaled each other. And thus r = r’.

99. Arbitrage Pricing Theory (APT)

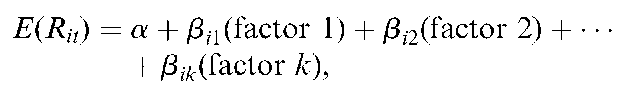

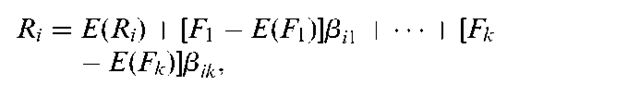

Ross (1970) derived a generalized capital asset pricing relationship called the arbitrage pricing theory (APT). To derive the APT, Ross assumed the expected rate of return on asset i at time t, E(Rit), could be explained by k independent influences (or factors):

where fiik measures the sensitivity of the ith asset’s returns to changes in factor k (sometimes called index k). In the terminology of factor analysis, bik’ s are called factor loading.

Using the prior equation, Ross shows that the actual return of the ith security can be defined as:

index k). In the terminology of factor analysis, bik’ s are called factor loading.

Using the prior equation, Ross shows that the actual return of the ith security can be defined as:

where [Fk — E(Fk)] represents the surprise or change in the kth factor brought about by systematic economic events.

Like the capital asset pricing model (CAPM), the APT assumes that investors hold diversified portfolios, so only systematic risks affect returns. [See also Capital asset pricing model (CAPM)] The APT’s major difference from the CAPM is that it allows for more than one systematic risk factor. The APT is a generalized capital asset pricing model; the CAPM is a special, one-factor case of the APT, where the one factor is specified to be the return on the market portfolio.

The APT does have a major practical drawback. It gives no information about the specific factors that drive returns. In fact, the APT does not even tell us how many factors there are. Thus, testing the APT is purely empirical, with little theory to guide researchers. Estimates of the number of factors range from two to six; some studies conclude that the market portfolio return is one of the return-generating factors, while others do not. Some studies conclude that the CAPM does a better job in estimating returns; others conclude that APT is superior.

The jury is still out on the superiority of the APT over the CAPM. Even though the APT is a very intuitive and elegant theory and requires much less restrictive assumptions than the CAPM, it currently has little practical use. It is difficult both to determine the return-generating factors and to test the theory.

In sum, an equilibrium asset pricing theory that is derived from a factor model by using diversification and arbitrage. It shows that the expected return on any risky asset is a linear combination of various factors.

100. Arbitrageur

An individual engaging in arbitrage.