TARGET-ZONE ARRANGEMENT

Target-zone arrangement is an international monetary arrangement in which countries vow to maintain their exchange rates within a specific band around agreed-upon, fixed, central exchange rates.

TAX ARBITRAGE

Tax arbitrage is a form of arbitrage that involves the shifting of gains or losses from one tax authority to another to profit from tax rate differences.

TAX EXPOSURE

Tax exposure is the extent to which an MNC’s tax liability is affected by fluctuations in foreign exchange values. As a general rule, only realized gains or losses affect the income tax liability of a company. Translation losses or gains are normally not realized and are not taken into account in tax liability. Some steps taken to reduce exposure, such as entering into forward exchange contracts, can create losses or gains that enter into tax liability. Other measures that can be taken have no income tax implications.

TECHNICAL ANALYSIS

As the antithesis of fundamental analysis, technical analysis concentrates on past price and volume movements—while totally disregarding economic fundamentals—to forecast a security price or currency rates. The two primary tools of technical analysts are charting and key indicators. Charting means plotting on a graph the stock’s price movement over time. For example, the security may have moved up and down in price, but remained within a band bounded by the lower limit (support level) and the higher limit (resistance level). Key indicators of market and security performance include trading volume, market breadth, mutual fund cash position, short selling, odd-lot theory, and the Index of Bearish Sentiment.

TECHNICAL FORECASTING

Technical forecasting involves the use of historical exchange rates to predict future values. For example, the fact that a given currency has increased in value over four consecutive days may provide an indication of how the currency will move tomorrow. It is sometimes conducted in a judgmental manner, without statistical analysis. Often, however, statistical analysis is applied in technical forecasting to detect historical trends. For example, a computer program can be developed to detect particular historical trends. There are also time series models that examine moving averages. Some develop a rule, such as, “The currency tends to decline in value after a rise in moving average over three consecutive periods.”

Technical forecasting of exchange rates is similar to technical forecasting of stock prices. If the pattern of currency values over time appears random then technical forecasting is not appropriate. Unless historical trends in exchange rate movements can be identified, examination of past movements will not be useful for indicating future movements. Technical factors have sometimes been cited as the main reason for changing speculative positions that cause an adjustment in the dollar’s value. For example, the Wall Street Journal frequently summarizes the dollar movements on particular days as shown below.

| Status of | ||

| Date | Dollar | Explanation |

| Oct. 14, 1999 | Weakened | Technical factors overwhelmed economic news |

| Nov. 18, 1999 | Weakened | Technical factors triggered sales of dollars |

| Dec. 16, 1999 | Weakened | Technical factors triggered sales of dollars |

| Apr. 14, 2000 | Strengthened | Technical factors indicated that dollars had been recently |

| oversold, triggering purchase of dollars |

These examples suggest that technical forecasting appears to be widely used by speculators who frequently attempt to capitalize on day-to-day exchange rate movements. Technical forecasting models have helped some speculators in the foreign exchange market at various times. However, a model that has worked well in one particular period will not necessarily work well in another. With the abundance of technical models existing today, some are bound to generate speculative profits in any given period.

Most technical models rely on the past to predict the future. They try to identify a historical pattern that seems to repeat and then try to forecast it. The models range from a simple moving average to a complex auto regressive integrated moving average (ARIMA). Most models try to break down the historical series. They try to identify and remove the random element. Then they try to forecast the overall trend with cyclical and seasonal variations. A moving average is useful to remove minor random fluctuations. A trend analysis is useful to forecast a long-term linear or exponential trend. Winter’s seasonal smoothing and Census XII decomposition are useful to forecast long-term cycles with additive seasonal variations. ARIMA is useful to predict cycles with multiplicative seasonality. Many forecasting and statistical packages such as Forecast Pro, Sibyl/Runner, Minitab, SPSS, and SAS can handle these computations.

TED SPREAD

The yield spread between U.S. Treasury bills and Eurodollars.

TEMPORAL METHOD

The temporal method translates assets valued in a foreign currency into the home currency using the exchange rate that exists when the assets are purchased. It is essentially the same as the monetary-nonmonetary method except in the treatment of physical assets that have been revalued. It applies the current exchange rate to all financial assets and liabilities, both current and long term. Physical, or nonmonetary, assets valued at historical cost are translated at historical rates. Because the various assets of a foreign subsidiary will in all probability be acquired at different times and exchange rates seldom remain stable for long, different exchange rates will probably have to be used to translate those foreign assets into the multinational’s home currency. Consequently, the MNC’s balance sheet may not balance.

EXAMPLE 116

Consider the case of a U.S. firm that on January 1, 20X1, invests $100,000 in a new Japanese subsidiary. The exchange rate at that time is $1 = ¥100. The initial investment is therefore ¥10 million, and the Japanese subsidiary’s balance sheet looks like this on January 1, 20X1.

| Yen | Exchange Rate | U.S. Dollars | |

| Cash | 10,000,000 | ($1 = ¥100) | 100,000 |

| Owners’ equity | 10,000.000 | ($1 = ¥100) | 100,000 |

Assume that on January 31, when the exchange rate is $1 = ¥95, the Japanese subsidiary invests ¥5 million in a factory (i.e., fixed assets). Then on February 15, when the exchange rate in $1 = ¥90, the subsidiary purchases ¥5 million of inventory. The balance sheet of the subsidiary will look like this on March 1, 20X1.

| Yen | Exchange Rate | U.S. Dollars | ||

| Fixed assets | 5,000,000 | ($1 | = ¥95) | 52,632 |

| Inventory | 5,000,000 | ($1 | = ¥90) | 55,556 |

| Total | 10,000,000 | 108,187 | ||

| Owners’ equity | 10,000,000 | ($1 | = ¥100) | 100,000 |

As can be seen, although the balance sheet balances in yen, it does not balance when the temporal method is used to translate the yen-denominated balance sheet tables back into dollars. In translation, the balance sheet debits exceed the credits by $8,187. How to cope with the gap between debits and credits is an issue of some debate within the accounting profession. It is probably safe to say that no satisfactory solution has yet been adopted.

A. Current U.S. Practice

U.S.-based MNCs must follow the requirements of Statement 52, “Foreign Currency Translation,” issued by the U.S. Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in 1981. Under Statement 52, a foreign subsidiary is classified either as a self-sustaining, autonomous subsidiary or as integral to the activities of the parent company. According to Statement 52, the local currency of a self-sustaining foreign subsidiary is to be its functional currency. The balance sheet for such subsidiaries is translated into the home currency using the exchange rate in effect at the end of the firm’s financial year, whereas the income statement is translated using the average exchange rate for the firm’s financial year. On the other hand, the functional currency of an integral subsidiary is to be U.S. dollars. The financial statements of such subsidiaries are translated at various historic rates using the temporal method (as we did in the example), and the dangling debit or credit increases or decreases consolidated earnings for the period.

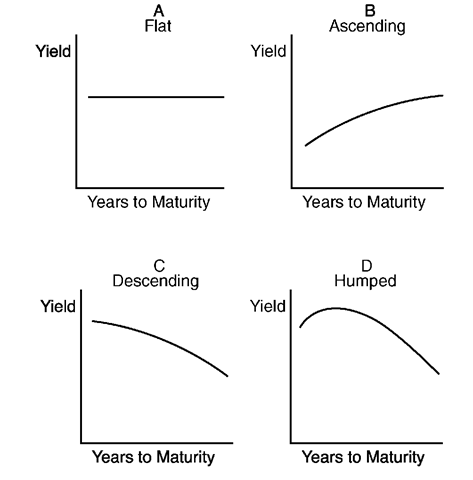

TERM STRUCTURE OF INTEREST RATES

The term structure of interest rates, also known as a yield curve, shows the relationship between length of time to maturity and yields of debt instruments. Other factors such as default risk and tax treatment are held constant. An understanding of this relationship is important to corporate financial officers who must decide whether to borrow by issuing long-or short-term debt. An understanding of yield-to-maturity for each currency is especially critical to an MNC’s CFO. It is also important to investors who must decide whether to buy long- or short-term bonds. Fixed income security analysts should investigate the yield curve carefully in order to make judgments about the direction of interest rates. A yield curve is simply a graphical presentation of the term structure of interest rates. A yield curve may take any number of shapes. Exhibit 105 shows alternative yield curves: a flat (vertical) yield curve (Exhibit 105A), a positive (ascending) yield curve (Exhibit 105B), an inverted (descending) yield curve (Exhibit 105C), and a humped (ascending and then descending) yield curve (Exhibit 105D). For the yield curve whose shape changes over time, there are three major explanations, or theories of yield curve patterns: (1) the expectation theory, (2) the liquidity preference theory, and (3) the market segmentation, or “preferred habitat,” theory.

EXHIBIT 105

Alternative Term-Structure Patterns

A. Expectation Theory

The expectation theory postulates that the shape of the yield curve reflects investors’ expectations of future short-term rates. Given the estimated set of future short-term interest rates, the long-term rate is then established as the geometric average of future interest rates.

EXAMPLE 117

At the beginning of the first quarter of the year, suppose a 91-day T-bill yields a 6% annualized yield, and the expected yield for a 91-day T-bill at the beginning of the second quarter is 6.4%. Under the expectation theory, a 182-day T-bill is equivalent to having successive 91-day T-bills and thus should offer investors the same annualized yield. Therefore, a 182-day T-bill issued at the beginning of the first quarter of the year should yield 6.2%, which is an arithmetic mean (average) of successive 91-day T-bills.

The beginning of the first quarter of the year should yield 6.2%, which is an arithmetic mean (average) of successive 91-day T-bills.

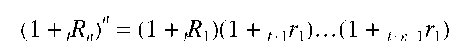

Mathematically, a current long-term yield is a geometric average of current and successive short-term yields, or

where the subscripts to the left of the variable, t, t + 1, …, signify the period and the subscripts to the right, 1, 2, …, n signify the maturity of the debt instrument. R is the current yield, and r is a future (expected) yield. A positive (ascending) yield curve implies that investors expect short-term rates to rise, while a descending (inverted) yield curve implies that they expect short-term rates to fall.

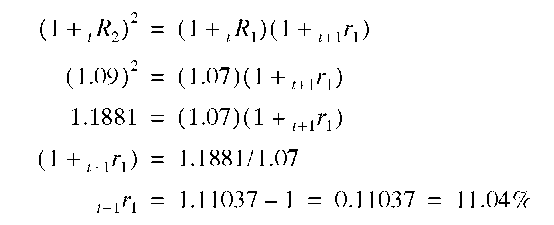

EXAMPLE 118

Suppose a current 2-year yield is 9%, or tR2 = .09, and a current 1-year yield is 7%, or lRt = .07. Then the expected 1-year future yield t+1rj is 0.11037, or 11.04%:

B. Liquidity Preference Theory

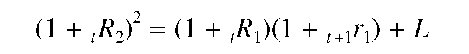

The liquidity preference theory contends that risk-averse investors prefer short-term bonds to long-term bonds, because long-term bonds have a greater chance of price variation, i.e., carry greater interest rate risk. Accordingly, the theory states that rates on long-term bonds will generally be above the level called for by the expectation theory. Current long-term bonds should include a liquidity premium as additional compensation for assuming interest rate risk. This theory is nothing but a modification of the expectation theory. Mathematically, a current 2-year rate is a geometric average of a current and a future 1-year rate plus a liquidity risk premium L:

Because of a liquidity premium, a yield curve would be upward-sloping rather than vertical when future short-term rates are expected to be the same as the current short-term rate.

C. Market Segmentation (Preferred Habitat) Theory

The market segmentation theory does not recognize expectations and emphasizes the rigidity in loan allocation patterns by lenders. Some lenders (such as banks) are required by law to lend primarily on a short-term basis. Other lenders (such as life insurance companies and pension funds) prefer to operate in the long-term market. Similarly, some borrowers need short-term money (e.g., to build up inventories), while others need long-term money (e.g., to purchase homes). Thus, under this theory, interest rates are determined by supply and demand for loanable funds in each maturity market spectrum. The yield curve for U.S. dollar-denominated debt issues is available at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York website

3-Ds

3-Ds stand for “dollar-denominated delivery.” Virtual currency options are also called 3-Ds (dollar-denominated delivery).

TIME VALUE

1. Time value of money; present values (discounting) of a future sum of money or an annuity and future values (compounding) of a present sum of money or an annuity. See also DISCOUNTING.

2. The amount by which the option value exceeds the intrinsic value. The theoretical value of an option consists of an intrinsic value and a time value.

TOKYO STOCK EXCHANGE

Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) is the largest stock exchange in Japan, with more than 80% of all transactions. Osaka is the second largest exchange, with about 15% of all transactions. By tradition, the TSE is an auction, order-driven market without market makers. Order clerks conclude trades by matching buyers and sellers without taking positions for their own accounts.

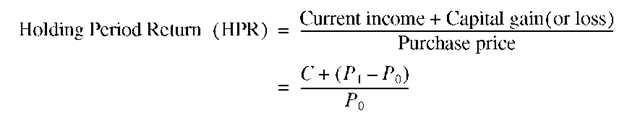

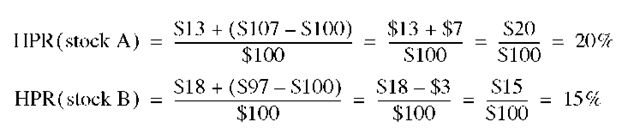

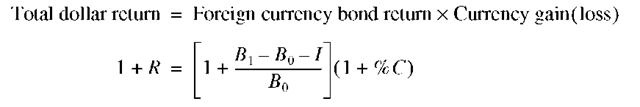

TOTAL RETURN

Total return (TR) is the most complete measure of an investment’s profitability. Total return on an investment equals: (1) periodic cash payments (current income) and (2) appreciation (or depreciation) in value (capital gains or losses). Current income (C) may be bond interest, cash dividends, rent, etc. Capital gains or losses are changes in market value. A capital gain is the excess of selling price (Pj) over purchase price (P0). A capital loss is the opposite. Return is measured considering the relevant time period (holding period), called a holding period return.

EXAMPLE 119

Consider the investment in stocks A and B over a one period of ownership:

| Stock | |

| A B | |

| Purchase price (beginning of year) | $100 $100 |

| Cash dividend received (during the year) | $13 $18 |

| Sales price (end of year) | $107 $97 |

The current incomes from the investment in stocks A and B over the one-year period are $13 and $18, respectively. For stock A, a capital gain of $7 ($107 sales price – $100 purchase price) is realized over the period. In the case of stock B, a $3 capital loss ($97 sales price – $100 purchase price) results.

Combining the capital gain return (or loss) with the current income, the total return on each investment is summarized below:

| Stock | ||

| Return | A | B |

| Cash dividend | $13 | $18 |

| Capital gain (loss) | _7 | 13} |

| Total return | $20 | $15 |

Thus, the return on investments A and B are:

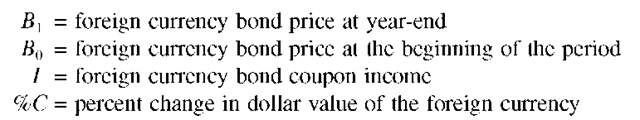

TOTAL RETURN FROM FOREIGN INVESTMENTS

In general, the total dollar return on an investment can be broken down into three separate elements: dividend/interest income, capital gains (losses), and currency gains (losses).

A. Bonds

The one-period total dollar return on a foreign bond investment R can be calculated as follows:

where

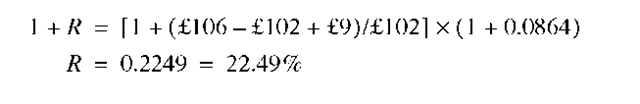

EXAMPLE 120

Suppose the initial British bond price is £102, the coupon income is £9, the end-of-period bond price is £106, and the local currency appreciates by 8.64% against the dollar during the period. According to the formula, the total dollar return is 22.49%:

Note: The currency gain applies to both the local currency principal and to the local currency return.

B. Stocks

Using the same terminology the one-period total dollar return on a foreign stock investment can be calculated as follows:

where

P1 = foreign currency stock price at year-end P0 = foreign currency stock price at the beginning of the period D = foreign currency dividend income %C = percent change in dollar value of the foreign currency

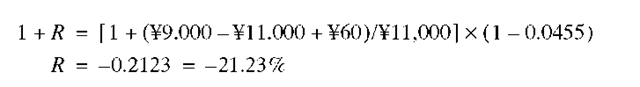

EXAMPLE 121

Suppose that, during the year, Honda Motor Company moved from ¥11,000 to ¥9,000, while paying a dividend of ¥60. At the same time, the exchange rate moved from ¥105 to ¥110. The total dollar return from this stock investment is a loss, which is computed as follows:

Note: The percent change in the yen rate is 0.00455 = (¥105 – ¥110)/ ¥110. In this example, the investor suffered both a capital loss on the foreign currency principal and a currency loss on the dollar value of the investment.

TRACKING STOCK

Issuing tracking stock is an increasingly popular corporate-financing technique. Tracking stock is a stock created by a company to follow, or track, the performance of one of its divisions—typically one that is in a line of business that is fast-growing and commands a higher industry price-to-earnings ratio than the parent’s main business. Some companies distribute tracking stock to their existing shareholders. Others sell tracking stock to the public, raising additional cash for themselves. Some companies do both. Tracking stock, however, does not typically provide voting rights.

TRADE ACCEPTANCE

Trade acceptance is a time or date draft which has been accepted by the drawee (or the buyer) for payment at maturity. Trade acceptances differ from bankers’ acceptances in that they are drawn on the buyer, carry only the buyer’s obligation to pay, and cannot become bankers’ acceptances or be guaranteed by a bank.

TRADE CREDIT INSTRUMENTS

Arrangements made to finance international trade credit are very much like the intracountry arrangements, but they also involve the extra complications of the international environment. The major trade credit instruments are:

• Letter of credit—a written statement made by a bank that it will pay a specified amount of money when certain trade conditions have been satisfied

• Draft—an order to pay someone (similar to a check)

• Banker’s acceptance—a draft that has been accepted by a bank

An example will help illustrate these ideas.

EXAMPLE 122

Consider a New York firm that wants to import $200,000 worth of Japanese CD player components. The firm first gets the Japanese company to grant it 60 days’ credit from the shipment date. Then the New York firm arranges a letter of credit through its New York bank, which is sent to the Japanese company. The Japanese company ships the equipment and presents a 60-day draft on the New York bank to its Japanese bank. Then the Japanese bank pays the Japanese company. The draft is then forwarded to the New York bank and, if all paperwork is in order, becomes a banker’s acceptance, which is a $200,000 debt that the New York bank owes the Japanese bank. At the end of 60 days the New York importer pays the New York bank, which in turn pays the acceptance. In the interim, the Japanese bank could sell the acceptance on the open market. The final owner of the banker’s acceptance would then present it to the New York bank for payment.

Note: There are at least four parties involved: an importer, an exporter, and their respective banks. Often there are other banks involved, too. The whole process has several detailed features and options associated with it. Finance companies and factors are also involved in financing trade credit.

TRANSACTION EXPOSURE

Transaction exposure is the extent to which the income from transactions is affected by fluctuations in foreign exchange values. This exposure arises whenever an MNC is committed to a foreign-currency-denominated transaction. Such exposure represents the potential gains or losses on the future settlement of outstanding obligations for the purchase or sale of goods and services at previously agreed prices and the borrowing or lending of funds in foreign currencies. An example would be a U.S. dollar loss, after the franc devalues, on payments received for an export invoiced in francs before that devaluation. Transaction exposure can be managed by contractual and operating hedges. The major contractual hedges use the forward, money, futures, and option markets, while operating strategies include the use of currency swaps, back-to-back (parallel) loans, and leads and lags in payment terms. Three contractual hedges are briefly explained below.

• Forward-market hedge. A forward hedge involves a forward contract and a source of funds to carry out that contract. The forward contract is entered into at the time the transaction exposure is created. Transaction exposure associated with a foreign currency can also be covered in the currency futures market.

• Money-market hedge. Like a forward-market hedge, a money-market hedge also employs a contract and a source of funds to fulfill that contract. In this case, however, the contract is a loan agreement. The MNC involved in the hedge borrows in one currency and exchanges the proceeds for another currency.

• Option-market hedge. An option-market hedge involves the purchase of a call (the right to buy) or put (the right to sell) option. This will allow the MNC to speculate the upside potential for depreciation or appreciation of the currency while limiting downside risk to a known (certain) amount.

EXAMPLE 123

Asiana Airlines has just signed a contract with Boeing to buy two new jet aircrafts for a total of $120,000,000, with payment in two equal installments. The first installment has just been paid. The next $60,000,000 is due three months from today. Asiana currently has excess cash of 50,000,000 won in a Seoul bank, from which it plans to make its next payment. It wishes to determine the method by which it could make its dollar payment and be assured of the largest remaining bank balance. The relevant data are given below.

| Value | Units | |

| Beginning Seoul bank cash balance | 90,000,000,000 | won |

| Account payable in 90 days | $60,000,000 | U.S. $ |

| Spot rate | 1100 | won/$ |

| Three-month forward rate | 1095 | won/$ |

| Spot rate in 3 months (forecast) | 1092 | won/$ |

| Korean 3-month interest rate | 5.00% | per annum |

| U.S. 3-month interest rate | 8.00% | per annum |

| OTC bank call option (90 days) | ||

| Strike price | 1090 | won/$ |

| Option premium (cost) | 0.50% | per annum |

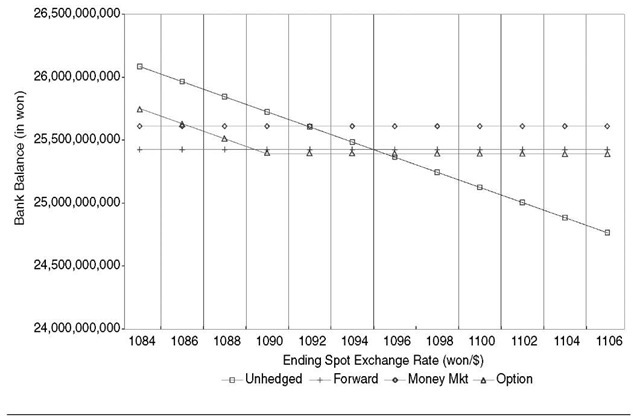

Exhibits 106 and 107 provide evaluation of four alternatives at various spot rates.

EXHIBIT 106

Transaction Hedge/Payment Evaluation (Korean won)

| Remaining | |||

| Alternative | Expected Cost | Bank Balance | |

| Unhedged | 65,520,000,000 | 25,605,000,000 | |

| Forward hedge | 65,700,000,000 | 25,425,000,000 | |

| Money-market hedge | 65,514,705,882 | 25,610,294,118 | |

| OTC bank option | Premium | 334,125,000 | |

| Exercise | 65,400,000,000 | 25,390,875,000 |

Note: All costs are stated at end of 90-day period.

EXHIBIT 107

Graphic Generation of Hedging Alternatives (ending bank balance in won)

| Spot rate | 1084 | 1086 | 1088 | 1090 | 1092 |

| Unhedged | 26,085,000,000 | 25,965,000,000 | 25,845,000,000 | 25,725,000,000 | 25,605,000,000 |

| Forward | 25,425,000,000 | 25,425,000,000 | 25,425,000,000 | 25,425,000,000 | 25,425,000,000 |

| Money market | 25,610,294,118 | 25,610,294,118 | 25,610,294,118 | 25,610,294,118 | 25,610,294,118 |

| Option | 25,750,875,000 | 25,630,875,000 | 25,510,875,000 | 25,390,875,000 | 25,390,875,000 |

Exhibit 108 graphs expected bank balances of alternative strategies.

EXHIBIT 108

Hedge Valuation for Asiana Airlines (at various ending spot exchange rates)

TRANSACTION RISK

Transaction risk is the risk resulting from transaction exposure and losses from changing foreign currency rates. It involves a receivable or a payable denoted in a foreign currency.

TRANSFERABLE LETTER OF CREDIT

A letter of credit (L/C) under which the beneficiary (exporter) has the right to instruct the paying bank to make the credit available to one or more secondary beneficiaries. No L/C is transferable unless specifically authorized in the letter of credit. Further, it can be transferred only once. The stipulated documents are transferred alone with the L/C.

TRANSLATION EXPOSURE

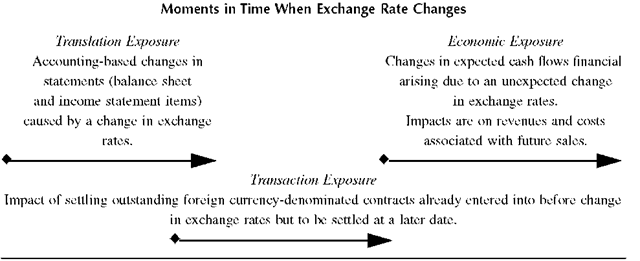

Also called accounting exposure, the impact of an exchange rate change on the reported consolidated financial statements of an MNC. An example would be the impact of a French franc devaluation on a U.S. firm’s reported income statement and balance sheet. The resulting translation (accounting) gain or losses are said to be unrealized—they are “paper” gains and losses. Exhibit 109 contrasts translation, transaction, and economic exposure. Exhibit 110 summarizes basic strategy for managing (hedging) translation exposure.

EXHIBIT 109

Comparison of Translation, Transaction, and Economic Exposure

EXHIBIT 110

Basic Strategy For Managing (Hedging) Translation Exposure

| Assets | Liabilities | |

| Hard currencies (Likely to appreciate) | Increase | Decrease |

| Soft currencies (Likely to depreciate) | Decrease | Increase |

The strategy involves increasing hard-currency assets and decreasing soft-currency assets, while simultaneously decreasing hard-currency liabilities and increasing soft-currency liabilities. For example, if a devaluation appears likely, the basic strategy would be to reduce the level of cash, tighten credit terms (to reduce accounts receivable), increase local currency borrowing, delay accounts payable, and sell the weak currency forward.

TRANSLATION GAIN OR LOSS

An accounting gain or loss resulting from changes caused by fluctuations in foreign currency-based receivables, payables, or other assets or liabilities.

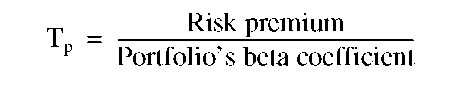

TREYNOR’S PERFORMANCE MEASURE

Treynor’s performance measure can be used to measure portfolio performance. It is concerned with systematic (beta) risk.

EXAMPLE 124

An investor wants to rank two stock mutual funds he owns. The risk-free interest rate is 6%. Information for each fund follows:

| Growth Fund | Return | Fund’s Beta | |

| A | 14% | 1.10 | |

| B | 12 | 1.30 | |

| tA | 14%-6% 1.10 | = 7.27 (First) | |

| tb | 12%-6% 130 | = 4.62 (Second) |

Fund A is ranked first because it has a higher return relative to Fund B.

The index can be computed based on information obtained from financial newspapers such as Barron’s and the Wall Street Journal.

TRIANGULAR ARBITRAGE

Also called a three-way arbitrage, triangular arbitrage eliminates exchange rate differentials across the markets for all currencies. This type of arbitrage involves more than two currencies. If the cross rate is not set properly, arbitrage may be used to capitalize on the discrepancy. When we consider that the bulk of foreign exchange trading involves the U.S. dollar, we note the role of comparing dollar exchange rates for different currencies to determine if the implied third exchange rates are in line. Since banks quote foreign exchange rates with respect to the dollar (the dollar is said to be the “numeraire” of the system), such comparisons are readily made. For instance, if we know the dollar price of pounds ($/£) and the dollar price of marks ($/DM), we can infer the corresponding pound price of marks (£/DM). Triangular arbitrage is a form of arbitrage seeking a profit as a result of price differences in foreign exchange among three currencies. This form of arbitrage occurs when the arbitrageur does not desire to operate directly in a two-way transaction, due to restrictions on the market or for any other reason. In this case, the arbitrageur moves through three currencies, starting and ending with the same one. Note: Like simple, two-way arbitrage, triangular arbitrage does not tie up funds. Also, the strategy is risk-free, because there is no uncertainty about the rates at which one buys and sells the currencies.

EXAMPLE 125

To simplify the analysis of arbitrage involving three currencies, let us temporarily ignore the bid-ask spread and assume that we can either buy or sell at one price. Suppose that in London $/£ = $2.00, while in New York $/DM = $0.40. The corresponding cross rate is the £/DM rate. Simple algebra shows that if $/£ = $2.00 and $/DM = 0.40, then £/DM = ($/DM)/($/£) = 0.40/2.00 = 0.2. If we observe a market where one of the three exchange rates—$/£, $/DM, £/DM—is out of line with the other two, there is an arbitrage opportunity.

Suppose that in Frankfurt the exchange rate is £/DM = 0.2, while in New York $/DM = 0.40, but in London $/£ = $1.90. Astute traders in the foreign exchange market would observe the discrepancy, and quick action would be rewarded. The trader could start with dollars and

1. Buy £1 million in London for $1.9 million as $/£ = $1.90.

2. The pounds could be used to buy marks at £/DM = 0.2, so that £1,000,000 = DM5,000,000.

3. The DM5 million could then be used in New York to buy dollars at $/DM = $0.40, so that DM5,000,000 = $2,000,000.

4. Thus, the initial $1.9 million could be turned into $2 million with the triangular arbitrage action earning the trader $100,000 (costs associated with the transaction should be deducted to arrive at the true arbitrage profit).

As in the case of the two-currency arbitrage covered earlier, a valuable product of this arbitrage activity is the return of the exchange rates to internationally consistent levels. If the initial discrepancy was that the dollar price of pounds was too low in London, the selling of dollars for pounds in London by the arbitrageurs will make pounds more expensive, raising the price from $/£ = $1.90 back to $2.00. (Actually, the rate would not return to $2.00, because the activity in the other markets would tend to raise the pound price of marks and lower the dollar price of marks, so that a dollar price of pounds somewhere between $1.90 and $2.00 would be the new equilibrium among the three currencies.)

EXAMPLE 126

Suppose the pound sterling is bid at $1.9809 in New York and the Deutsche mark at $0.6251 in Frankfurt. At the same time, London banks are offering pounds sterling at DM 3.1650. An astute trader would sell dollars for Deutsche marks in Frankfurt, use the Deutsche marks to acquire pounds sterling in London, and sell the pounds in New York. Specifically, the trader would

1. Acquire DM1,599,744.04 ($1,000,000/$0.6251) for $1,000,000 in Frankfurt,

2. Sell these Deutsche marks for £505,448.35 (1,599,744.04/DM3.1650) in London, and

3. Resell the pounds in New York for $1,001,242.64 (£505,448.35 x $1.9809).

Thus, a few minutes’ work would yield a profit of $1,242.64 ($1,001,242.64 – $1,000,000). In effect, the trader would, by arbitraging through the DM, be able to acquire sterling at $1.9784 in London ($0.6251 x 3.1650) and sell it at $1.9809 in New York. Again, as can be seen in this example, the arbitrage transactions would tend to cause the Deutsche mark to appreciate vis-a-vis the dollar in Frankfurt and to depreciate against the pound sterling in London; at the same time, sterling would tend to fall in New York.

Opportunities for such profitable currency arbitrage have been greatly reduced in recent years, given the extensive network of people—aided by high-speed, computerized information systems—who are continually collecting, comparing, and acting on currency quotes in all financial markets. The practice of quoting rates against the dollar makes currency arbitrage even simpler. The result of this activity is that rates for a specific currency tend to be the same everywhere, with only minimal deviations due to transaction costs.

TRIANGULATION

Triangulation is the method of conversion used under the new euro system. The conversion has to be made through the euro—for example, Dutch guilders to euros to francs, using the fixed conversion rates.

TRUST RECEIPT

A trust receipt is an instrument that acknowledges that the borrower holds specified property in trust for the lender. The lender retains title. The goods are subject to repossession by the bank. The trust receipts are always used when merchandise is financed via acceptances under letters of credit. When the lender receives the sale proceeds, title is given up.

TWO-TIER FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKET

An arrangement of two exchange markets—a formal market (at the official rate) for certain transactions and a free market for remaining transactions.

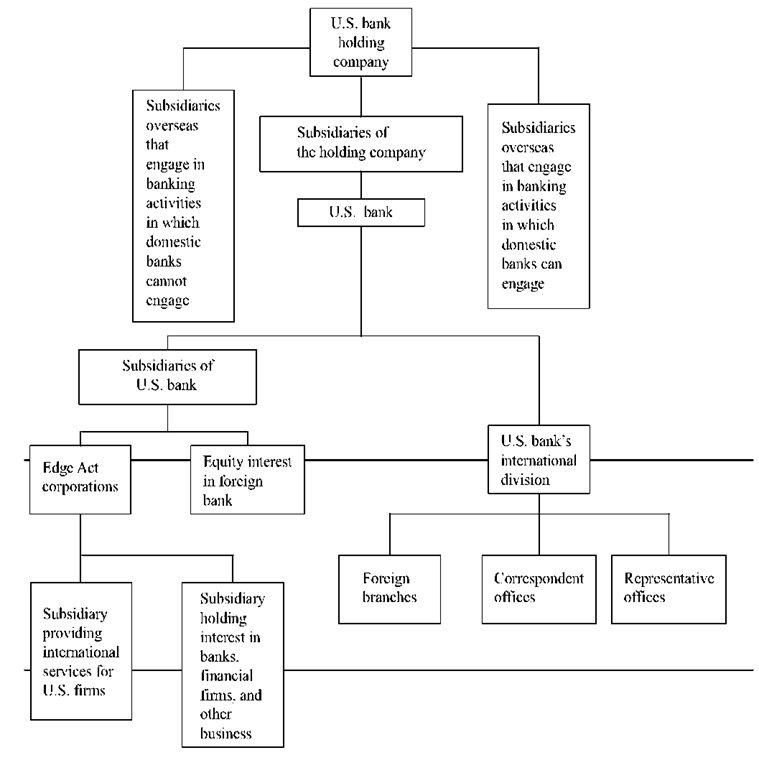

TYPES OF OVERSEAS BANKING SERVICES

There are a number of organizational forms that banks may use to deliver international banking services to their customers. The primary forms are (1) correspondent banks, (2) representative offices, (3) branch banks, (4) foreign subsidiaries and affiliates, (5) Edge Act corporations, and (6) international banking facilities (IBFs). Exhibit 111 shows a possible organizational structure for the foreign operations of U.S. banks. Though possible, all these forms need not exist for any individual bank. Exhibit 112 summarizes advantages and disadvantages of each type of form.

EXHIBIT 111

Organizational Structure for a U.S. Bank’s International Operations

EXHIBIT 112

Advantages and Disadvantages of Types of Overseas Banking Services

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Correspondent banks | Minimal cost form of market entry | Low priority given to the needs of U.S |

| No investment in staff or facilities | customers | |

| Having multiple sources of business | Difficulty of obtaining due to capital | |

| given and received | restrictions | |

| Referrals to local banking opportunities | Difficult to arrange certain types of | |

| Ability to cash in on local knowledge and | credits | |

| contacts | Credit not provided regularly and | |

| extensively by the correspondent |

| Representative offices | Low-cost entry to foreign markets | Inability to penetrate the foreign market |

| Efficient delivery of services | more effectively | |

| Attracting additional business | Expensive because capital is not | |

| Preventing losses of current business | generated | |

| Difficult to attract qualified personnel | ||

| Inability to conduct general banking | ||

| activities | ||

| Foreign branches | Better control over foreign operations | High-cost form of entry into a foreign |

| Enhanced ability to offer direct and | market | |

| integrated services to customers | Difficult and expensive to train branch | |

| Improved ability to manage customer | managers | |

| relationships | ||

| Ability to conduct a full range of services | ||

| Foreign subsidiaries and | Immediate access to local deposit | Expensive |

| affiliates | markets | Highly risky |

| Ability to use an established network of | Difficult to make work effectively | |

| local contacts and clients |