The next editing example is a scene from A Walk on the Wild Side, a film written by a number of writers, based on Nelson Algren’s novel of the same name.

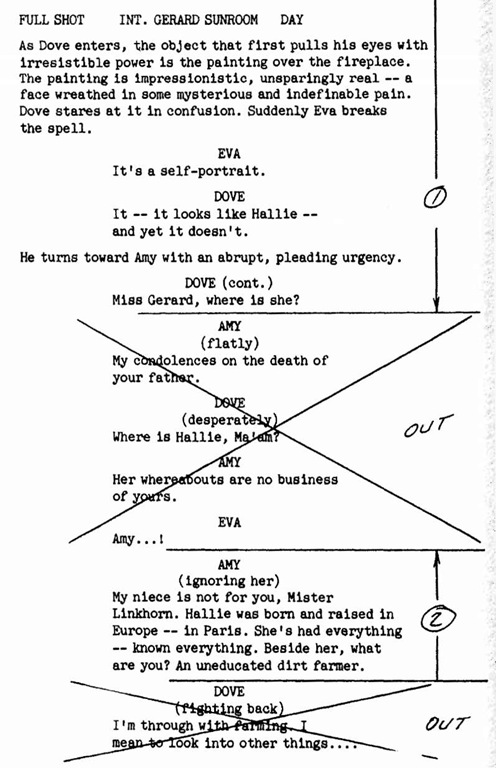

In this scene, the problem is twofold: first, to shorten it as much as possible, since too much time is taken to deliver its simple message, and second, to eliminate as much as possible of its mawkish flavor. Figure 12 presents the scene as written.

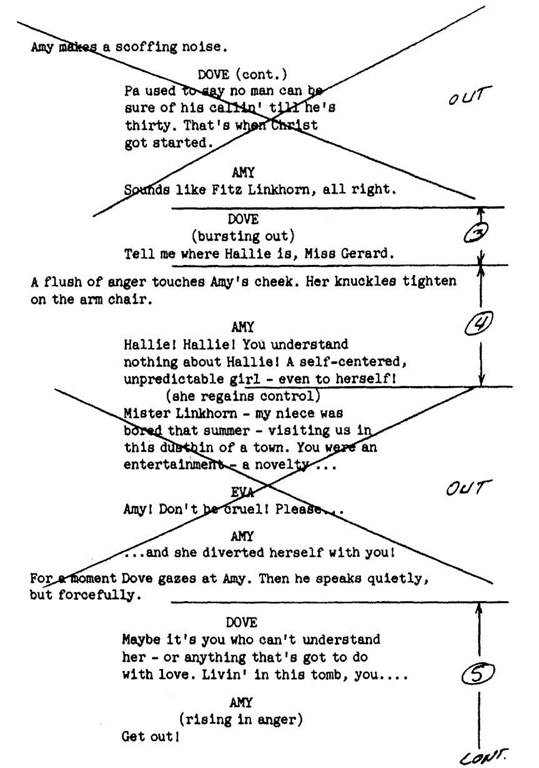

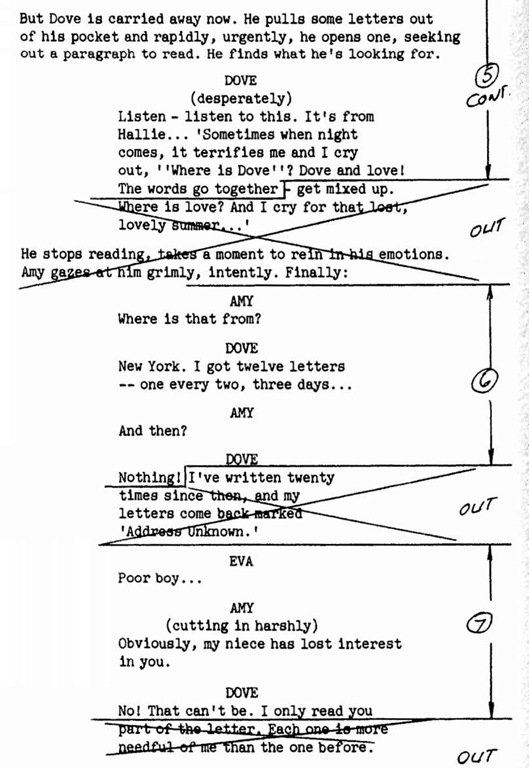

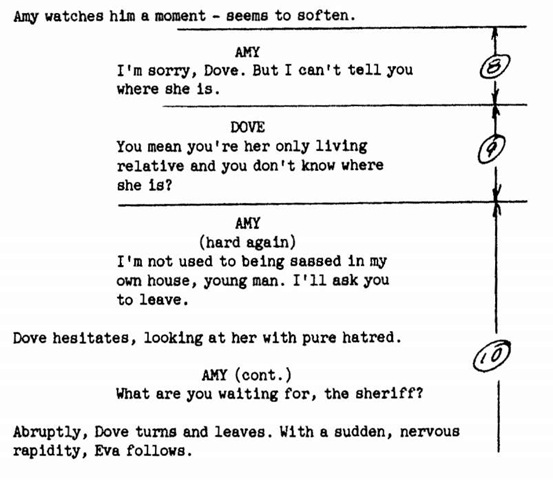

Figure 13, which follows, indicates the proposed cuts. In this instance, the alignment of the retained portions follows the original sequence, with deletions accomplished by cutting to angles that were originally shot. The reedited version is more than one-third shorter and immeasurably less maudlin.

Amy’s line in (2) is pure exposition, but its nature is camouflaged to some extenjt by using the information as a basis for making the scene one of conflict.

FULL SHOT INT. GERARD SUNROOM DAY

As Dove enters, the object that first pulls his eyes with irresistible power is the painting over the fireplace. The painting is impressionistic, unsparingly real — a face wreathed in some mysterious and indefinable pain. Dove stares at it in confusion. Suddenly Eva breaks the spell.

Figure 12

Figure 12

Figure 12

Figure 12

The next deletion following (2) eliminates Dove’s attempt at self-defense, an attempt which weakens his position and his character. His ignoring of Amy’s attack lends him dignity, and his persistence drives Amy into her brief outbreak, which tells us all we need to know at this point about her feelings toward her niece, and possibly a little about Hallie.

The deletion after (4) eliminates an unnecessarily cruel, and therefore unbelievable, reaction on Amy’s part.

Dave’s maudlin speeches are not only corny (since they come so early in the film that neither the story’s basic situation nor Dove’s character are yet established), they also tend to present him as a weak, unattractive person.

Figure 13

Figure 13

Figure 13

Figure 13

Figure 14 shows the scene as reedited, with the necessary angles indicated. This kind of editing will not make a bad scene great, but it can make it acceptable and useful. Since, unfortunately, few films or film scripts are perfect, an editor who can skillfully accomplish this kind of corrective manipulation will never lack a professional "home."

Figure 14

Figure 14

Figure 14

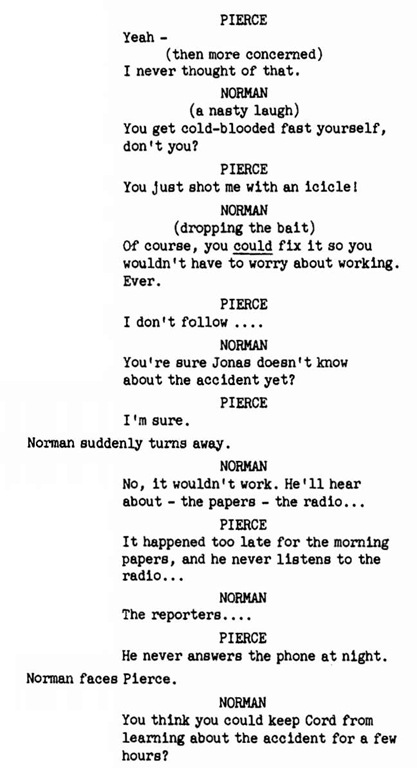

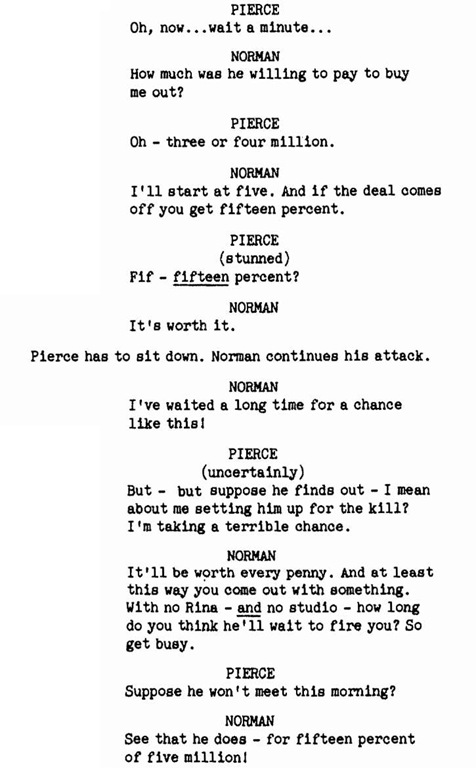

Our third example is another scene from The Carpetbaggers. It is neither a bad nor an inadequate scene—in truth, Bob Cummings and Marty Balsam, two exceptional actors, played it extremely well. It is used here only to show what kind of manipulation is possible if such a scene should require shortening, and how new elements, not originally planned or shot, can be inserted.

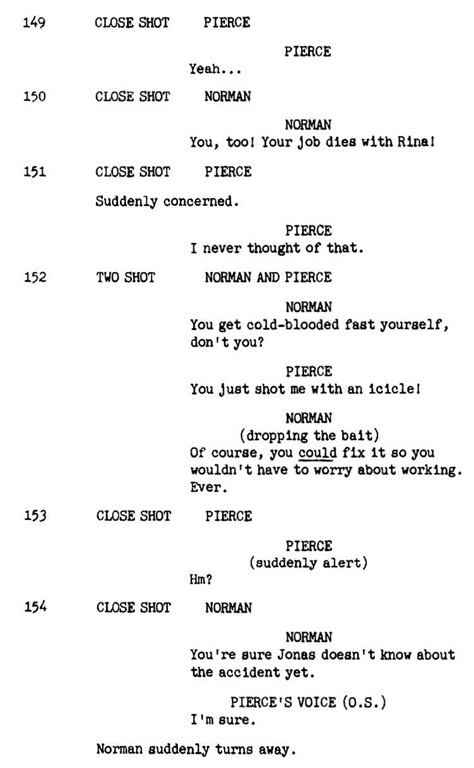

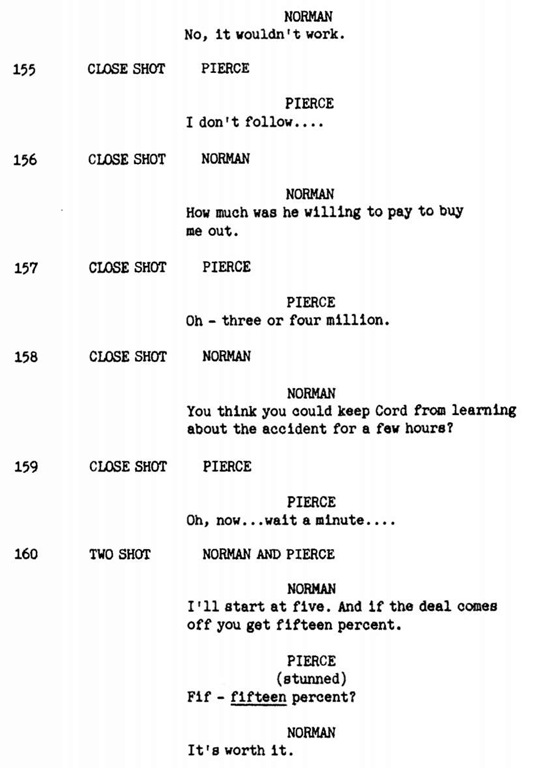

Figure 15 is the scene in a master shot, as written.

Figure 15

Figure 15

Figure 15

Figure 15

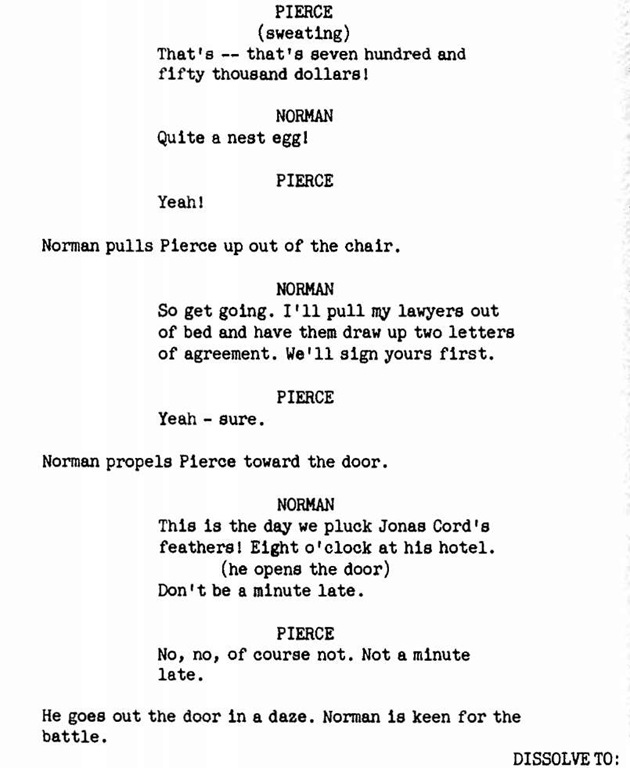

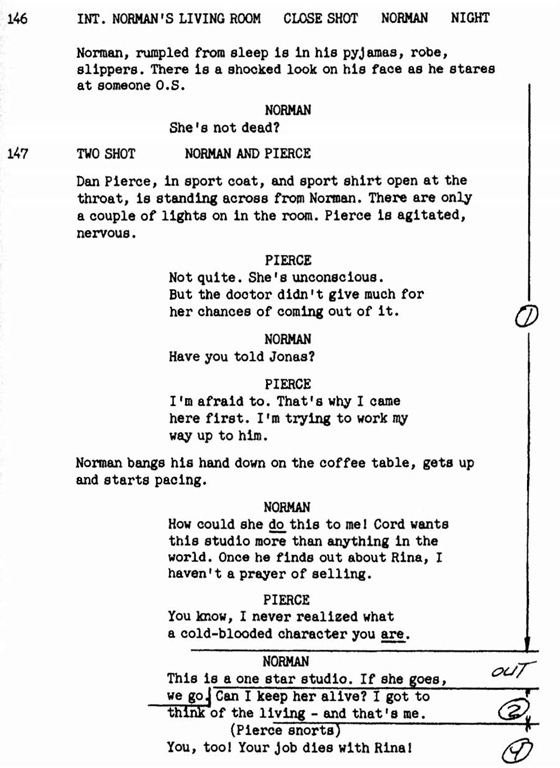

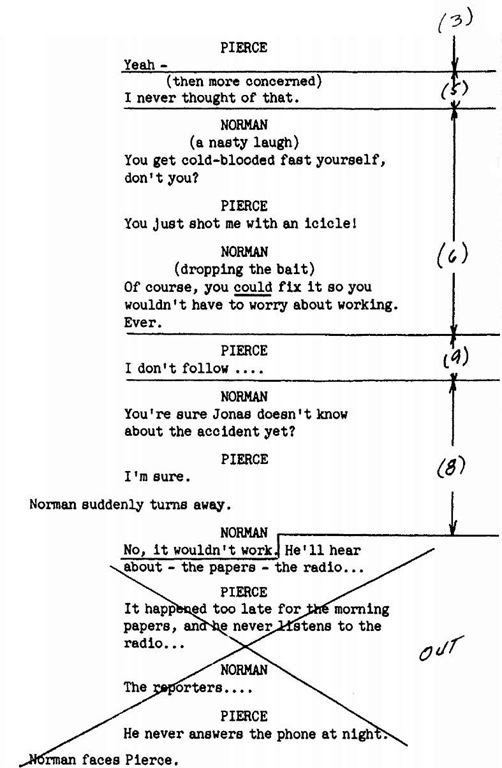

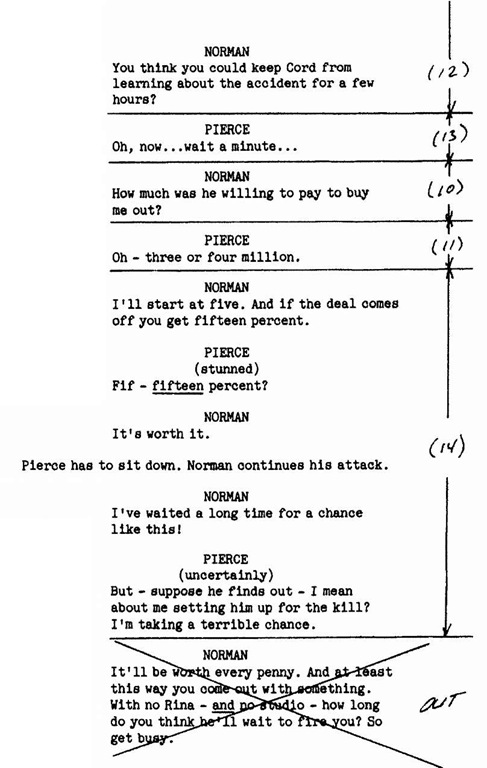

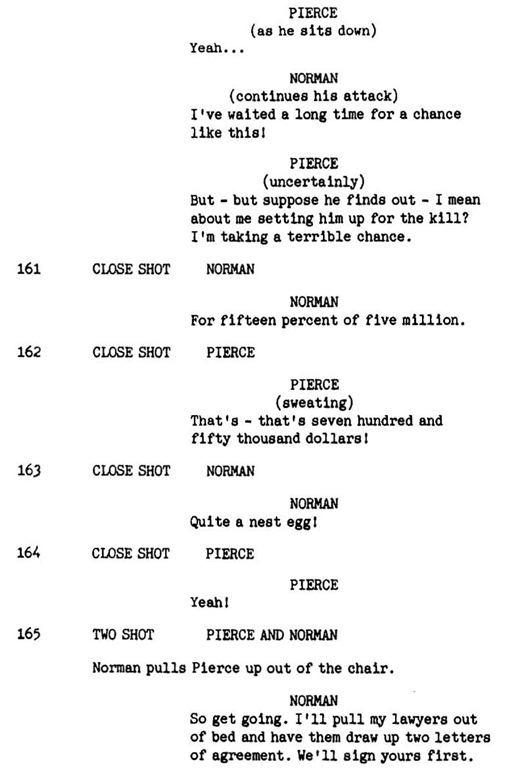

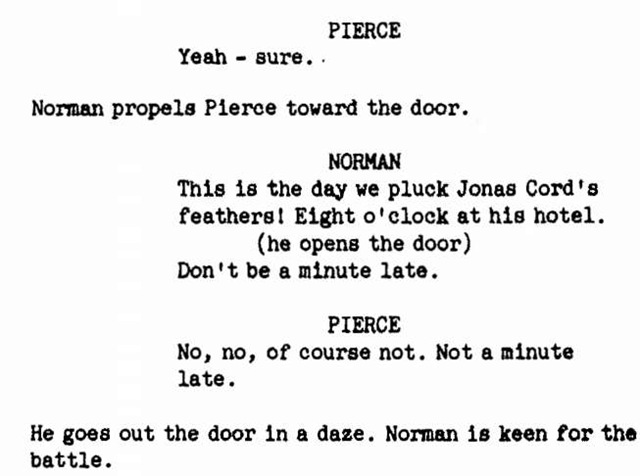

Figure 16 indicates the deletions, which total about three-fourths of a page, and the sequence of cuts in a new alignment.

Figure 16

Figure 16

Figure 16

Figure 16

Now, the analysis: The first deletion, after cut (1), is made to get a more spontaneous, emotional response to Pierce’s accusation. Cuts (2), (3|, (4), and (5), which follow, are rearranged and played in close shots to continue this more realistic and more understandable self-justification by Norman. It also accentuates Pierce’s awakening to his own tenuous situation.

The next three lines follow in original order, but then a cut is inserted that was not in the original scene, nor was such a cut shot. But it is easily manufactured by finding a suitable reaction from one of Pierce’s close-ups, even if an "out take" has to be printed. The sound "Hm?" is "looped" in during postproduction without any additional effort or expense since a certain amount of looping for various scenes in the film is almost always required.

The cut is inserted at this point in the scene to show Pierce beginning to catch on to Norman’s ploy somewhat earlier than in the original scene. It also reminds the viewer of Pierce’s "conman" attributes.

Cut (9) is reserved for a moment as (8) follows the manufactured close shot (153). Now (9) drops into place, primarily to keep Norman rolling. Cuts (10) (11) (12) and (13) are rearranged to permit a slightly more subtle approach from Norman. Cut (14) now continues as in the original lineup, with the hook being set. Only one more tug at the line is needed here, and it is most effectively furnished by an appeal to Pierce’s greed through the direct reference "for fifteen percent of five million!" Considering the characters involved, this attack is much more effective than reiteration of the threat to Pierce’s job. New jobs are not that hard to find, but $750,000 is!

It serves to separate Norman’s non-sequitor lines, "It’s worth it" and "I’ve waited (etc.)" and to strengthen Pierce’s decision just before his final doubt. The "Yeah," really a loud breath, is stolen from the sound track of one of his takes or looped later if a satisfactory reading cannot be found. It is inserted just when Pierce sits down, which will help to distract the viewer’s attention from his lips. The sound, in fact, requires no lip movement, and its inclusion will by no means appear to be obvious. This kind of "manufacturing" can be accomplished easily, even on a much more complex level, and it should always be kept in mind as a possible lifebelt in severely troubled, sink-or-swim situations.

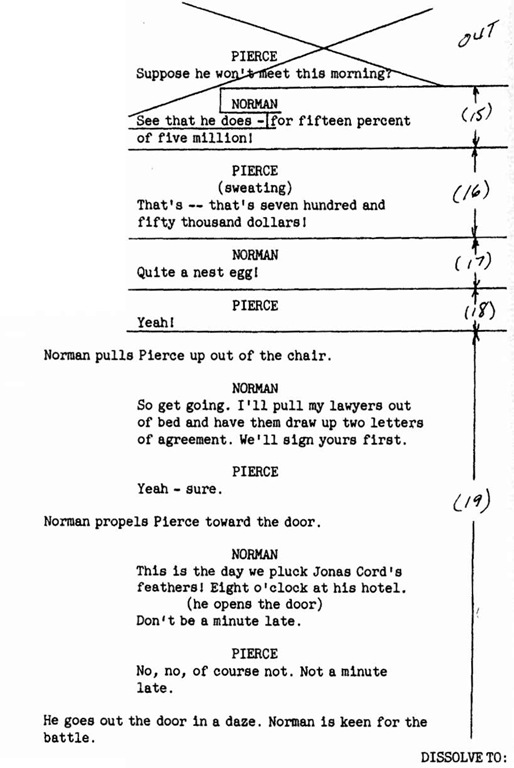

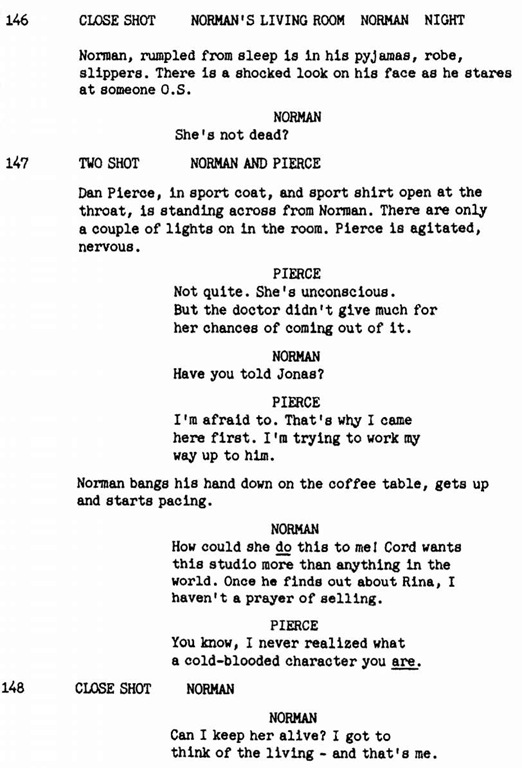

The rest of the scene runs as written, except that cuts (15J, (16), (17), and (18) are played in close shots to allow for neater timing and closer interplay.

Figure 17

Figure 17

Figure 17

Figure 17

Figure 17