In This Chapter

Getting the skinny on workbooks and worksheets Understanding the parts of a worksheet Working with cells, ranges, and references Applying formatting

Figuring out how to use the Help system

Writing formulas

Using functions in formulas

Using nested functions

Using array functions

Excel is to computer programs what a Porsche or a Ferrari is to the automotive industry. Sleek on the outside and a lot of power under the hood. Excel is also like a truck — it can handle all your data, lots of it. In fact, a single worksheet has 16,777,216 places to hold data. And that’s on just one worksheet!

Excel is used in all types of businesses. And you know how that’s possible? By being able to store and work with any kind of data. It does not matter if you are in finance, sales, run a video store, organize wilderness trips, or just want to track the scores of your favorite sports teams — Excel can handle all of it. The number crunching ability of Excel is just awesome! And so easy to use!

Just putting a bunch of information on worksheets does not crunch the data or give you sums, results, or any type of analysis. If you want to just store your data somewhere, sure you can use Excel, or you can get a database program

instead. In this topic, we show you how to build formulas and how to use the dozens of built-in functions that Excel provides. That’s where the real power of Excel is — making sense of your data.

Don’t fret that this is a challenge and that you may make mistakes. We did when we were learning. Besides, Excel is very forgiving. It won’t crash on you. Excel usually tells you when you made a mistake, and sometimes it even helps you to correct it. How many programs do that!?

But first the basics. This first chapter gives you the springboard you need to use the rest of the topic. We wish topics like this were around when we were learning about computers. We had to stumble through a lot of this.

Working with Excel Fundamentals

Before you can write any formulas or crunch any numbers, you have to know where the data goes. And how to find it again. We wouldn’t want your data to get lost! Knowing how worksheets store your data and present it is critical to your analysis efforts.

Understanding workbooks and worksheets

A workbook is the same as a file. Excel opens and closes workbooks, just as a word processor program opens and closes documents. Use the File Open, File Save, and File Close menu commands for opening and closing the workbooks. One detail you should know about Excel files is that the file extension is .xls.

Excel files have the .xls extension.

When Excel starts up, it displays a blank workbook ready for use. If at anytime you need another new workbook, choose File O New from the menu and select a Blank workbook. When you have more than one workbook open, you pick the one you want to work on by selecting it in the list of workbooks under the Window menu.

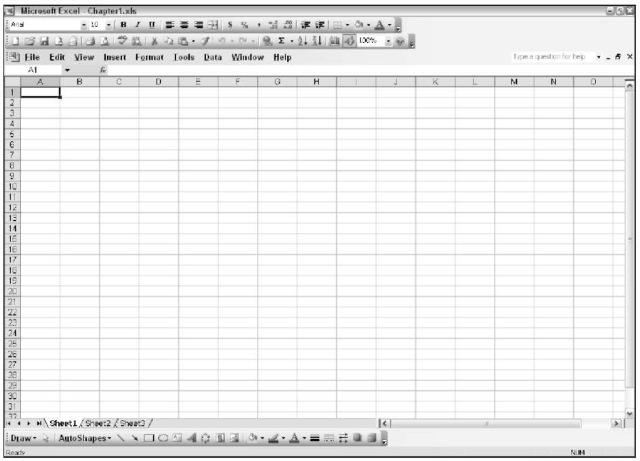

A worksheet is where your data actually goes. A workbook contains at least one worksheet. If you didn’t have at least one, where would you put the data? Figure 1-1 shows an open workbook that has three sheets — Sheet1, Sheet2, and Sheet3. You can see these on the worksheet tabs near the bottom left of the screen.

Figure 1-1:

Looking at a workbook and worksheets.

At any given moment, one worksheet is always on top. In Figure 1-1, Sheet1 is on top. Another way of saying this is Sheet1 is the active worksheet. There is always one and only one active worksheet. To make another worksheet active, just click its tab.

Worksheet, spreadsheet, and just plain old sheet are used interchangeably to mean the worksheet.

Guess what’s really cool? You can change the name of the worksheets. Names like Sheet1 and Sheet2 are just not exciting. How about Baseball Card Collection or Last Year’s Taxes. Well actually Last Year’s Taxes isn’t too exciting either. The point is you can give your worksheets meaningful names. You have two ways to do this:

Double-click the worksheet tab and then type in a new name.

Right-click on the worksheet tab, select Rename from the pop-up list, and then type in a new name.

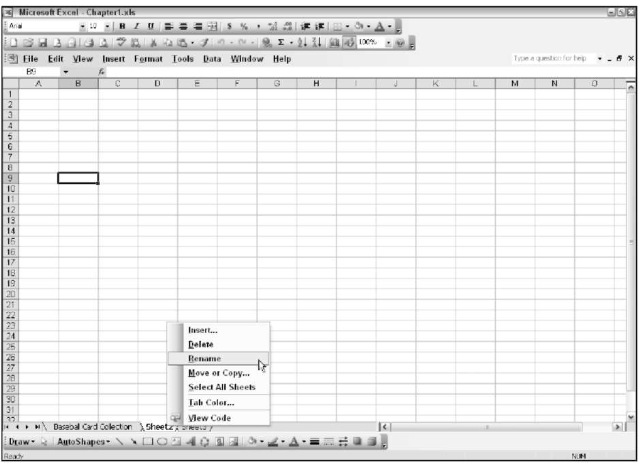

Figure 1-2 shows one worksheet name already changed and another about to be changed by right-clicking its tab.

Figure 1-2:

Changing the name of a worksheet.

You can try changing a worksheet name on your own. Do it the easy way:

1. Double-click a worksheet’s tab.

2. Type in a new name and press Enter.

You can change the color of worksheet tabs. Right-click on the tab and select Tab Color from the list.

To insert a new worksheet into a workbook, choose Insert O Worksheet from the menu. To delete the active worksheet, choose Edit Delete Sheet from the menu. Yeah, we know. It would be easier if these were under the same menu. But in all likelihood, you will be inserting new worksheets more than deleting them.

Don’t delete a worksheet unless you really mean to. You cannot get it back after it is gone. It does not go into the Windows Recycle Bin.

You can insert many new worksheets. The limit of how many is based on your computer’s memory but you should have no problem inserting 200 or more. Of course we hope you have a good reason for having so many. Which brings us to the next point.

Worksheets organize your data. Use them wisely and you will find it easy to manage your data. For example, let’s say you are the boss (We thought you’d like that!), and you have 30 employees that you are tracking information on over the course of a year. You might have 30 worksheets — one for each employee. Or you might have twelve worksheets — one for each month. Or you may just keep it all on one worksheet. How you use Excel is up to you, but Excel is ready to handle whatever you throw at it.

Excel has a default of how many worksheets appear in a new workbook. The default is usually three. You can change this number by choosing Tools O Options from the menu and changing the “Sheets in new workbook” setting on the General tab in the Options dialog box.

Working with rows, columns, cells, and ranges

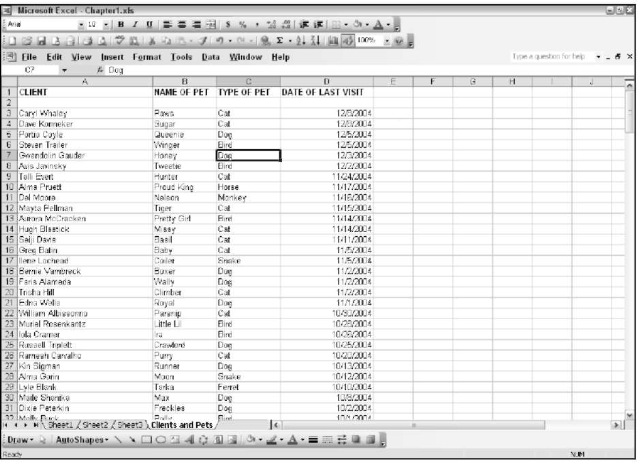

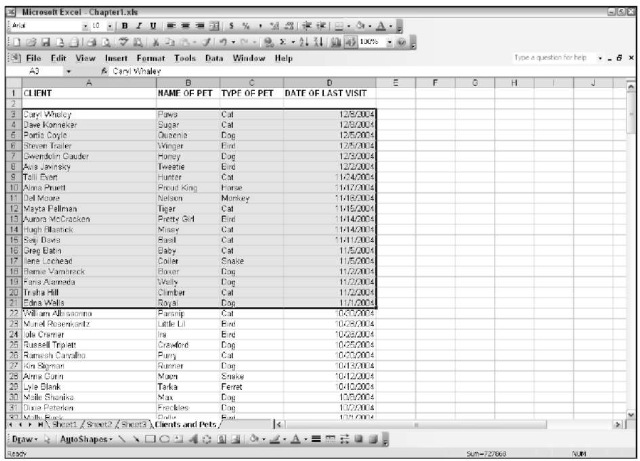

A worksheet contains cells. Lots of them. Millions of them. This might seem unmanageable but actually it’s pretty straightforward. Figure 1-3 shows a worksheet filled with data. We use this figure to take a look at the components of a worksheet.

Figure 1-3:

Looking at what goes into a worksheet.

Each cell can contain data or a formula. In Figure 1-3, the cells contain data. Some or even all the cells could contain formulas, but that’s not the case here.

Columns have letter headers — A, B, C, and so on. These can be seen listed horizontally just above the area where the cells are. After you get past the 26th column, a double lettering system is used — AA, AB, and so on. Rows are listed vertically down the left side of the screen. Rows use a numbering system.

You find cells at the intersection of rows and columns. Cell A1 is the cell at the intersection of column A and row 1. A1 is the cell’s address. There is always an active cell. That is, a cell in which any entry would go into should you start typing. The active cell has a border around it. Also the contents of the active cell are seen in the Formula Bar, which we will get to in a moment.

When we speak of or reference cells, we are referring to the address of the cell. The address is the intersection of a column and row. To talk about cell D20 means to talk about the cell that you find at the intersection of column D and row 20.

In Figure 1-3, the active cell is C7. You have a couple of ways to see this. For starters, Cell C7 has a border around it. Also notice that the column head C is shaded, as well as the row number 7. Just above the column headers are the Name Box and the Formula Bar. The Name Box is all the way to the left and shows the active cell’s address of C7. To the right of the name box, the Formula Bar shows the contents of cell C7.

If the Formula Bar is not visible, choose View O Formula Bar from the menu to make it visible.

Getting to know the Formula Bar

You use the Formula Bar quite a bit as you work with formulas and functions. You use it to enter and edit formulas; it’s the long entry box that starts in the middle of the bar. When you enter a formula into this box, you then click the little check mark button to finish the entry. The check mark button is only visible when you are entering a formula. The alternative is to enter formulas directly into the cell. Even so, the Formula

Bar displays the contents of cells. When you want to see just the contents of a cell that has a formula, make that cell active and look at its contents in the Formula Bar. Cells that have formulas do not normally display the formula, but instead display the result of the formula. When you want to see the actual formula, the Formula Bar is the place to do it.

A range is a group of adjacent cells. Technically, even a single cell is a range. But we are talking about something bigger here. Make a range right now. Here’s how:

1. Position the mouse over the first cell.

2. Press and hold the left mouse button down.

3. Move the cursor to the last cell (this is called dragging).

4. Release the mouse button.

Figure 1-4 shows the result. We selected a range of cells. The address of this range is A3:D21. Let’s pick that address apart.

A range address looks like two cell addresses put together, with a colon (:) in the middle. And that’s what it is! A range address starts with the address of the cell in the upper-left of the range, then has a colon, and then ends with the address of the cell in the lower-right. Ranges are always rectangular in shape.

Figure 1-4:

Selecting a range of cells.

One more detail about ranges — you can give them a name. This is a great feature because you can think about a range in terms of what is used for, instead of what its address is.

For example, say you have a list of clients on a worksheet. What’s easier — thinking of exactly which cells are occupied, or thinking that there is your list of clients?

Throughout this topic, we use ranges made of cell addresses and ranges, which have been given names. So it’s time to get your feet wet creating a named area, as it’s called. Here’s what you do:

1. Select an area of the worksheet.

To do this position the mouse over a cell, click and drag the mouse around. Release the mouse button when done.

2. Choose Insert O Name O Define from the menu to open the Define Name dialog box.

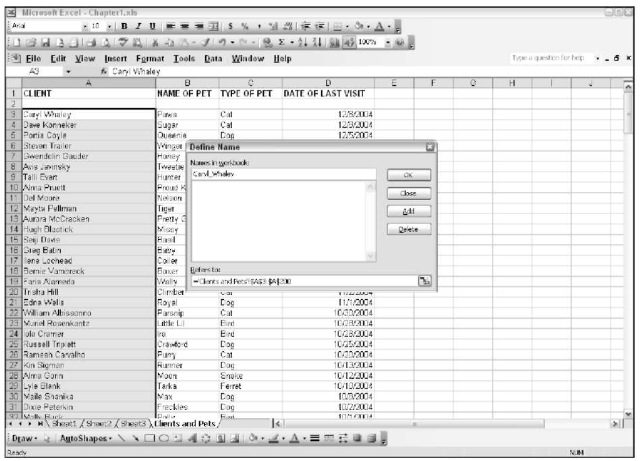

Figure 1-5 shows you how it looks so far.

Excel guesses that you want to name the area with the value it finds in the top cell of the range.

3. Change the name if you need to and click the Add button.

Figure 1-6 shows an example of the name being changed to “Clients.”

Figure 1-5:

Adding a name to the workbook.

Figure 1-6:

Completing adding a name.

4. Click the Close button.

That’s it. Hey, you’re already on your way to being an Excel pro!

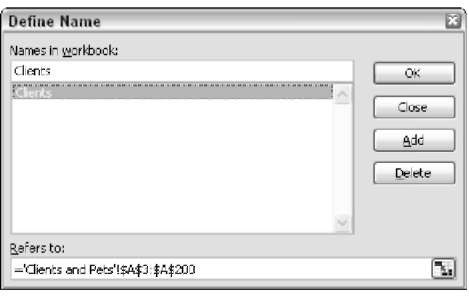

Now that you have a named area, you can easily select your data at any time. Just go to the Name box and select it from the list. See Figure 1-7 for how to find the range named Clients. After you click the name, the worksheet area is selected.

Figure 1-7:

Using the name to find the data area.

Throughout the topic are examples using rows, columns, cells, and ranges. Chapter 14 explains certain functions that work with these as well — ADDRESS,ROWS, COLUMNS, OFFSET, and more.

Formatting your data

Of course you will want to make your data look all spiffy and shiny. Bosses like that. If you see the number 98.6 — is this someone’s temperature? Is it a score on a test? Or is it meant to be ninety-eight dollars and sixty cents? Is it a percentage? Any of these formats are correct:

98.6

$98.60 98.6%

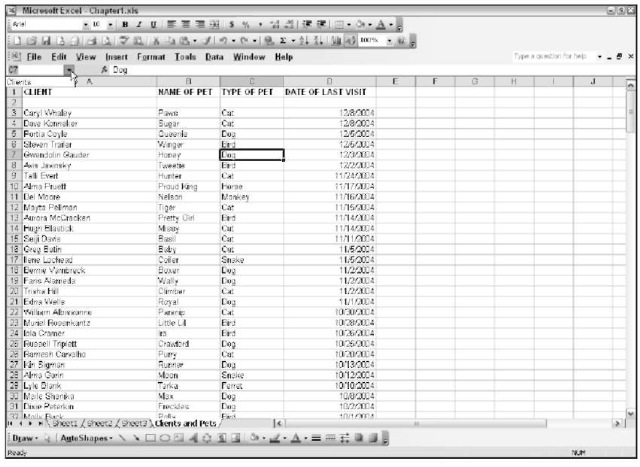

Excel lets you format your data in just they way you need. For starters, there is the Formatting toolbar. Imagine it, formatting is so important the makers of Excel made a toolbar for it. Table 1-1 shows some of the toolbar buttons and what they are used for.

If the Formatting toolbar is not visible, choose View O Toolbars from the menu to make it appear.

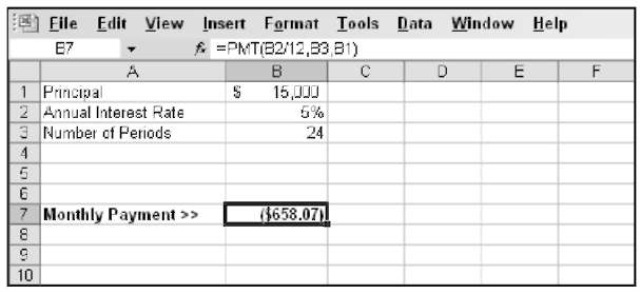

Figure 1-8 shows how formatting helps in the readability and understanding of a worksheet. Cell B1 has a monetary amount and is formatted as currency. Cell B2 is formatted as a percent. The actual value in cell B2 is .05. Cell B7 is also formatted as currency. The currency format displays a negative value in parenthesis. This is just one of the formatting options for currency. Chapter 5 explains further about formatting currency.

Figure 1-8:

Formatting data.

Besides the Formatting toolbar, you have the Format Cells dialog box. This is the place to go for all your formatting needs beyond what’s available on the toolbar. You can even create custom formats. Two ways to display the Format Cells dialog box are:

Choose Format Cells from the menu.

Right-click on any cell and select Format Cells from the pop-up list.

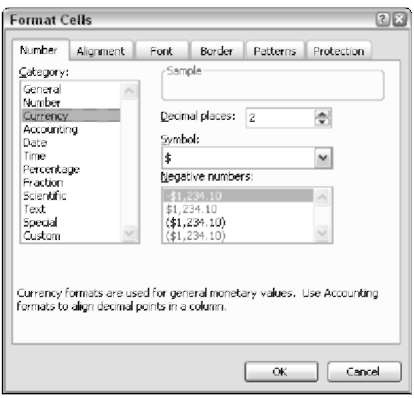

Figure 1-9 shows the Format Cells dialog box. So many settings are there it makes our heads spin! We discuss using this dialog box and formatting in general more extensively in Chapter 5.

Figure 1-9:

Using the Format Cells dialog box for advanced formatting options.

Getting help

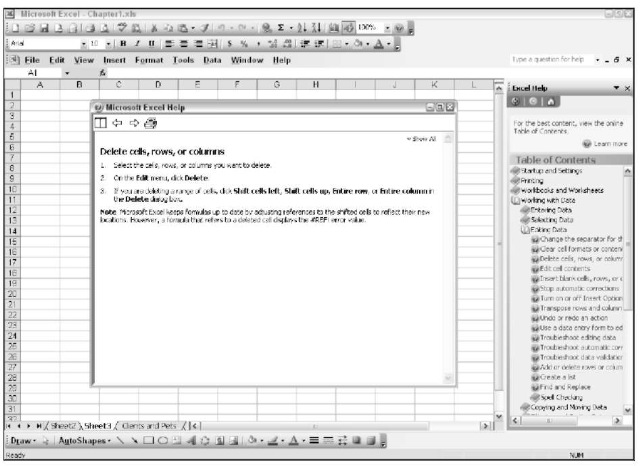

Excel is complex, we can’t deny that. And lucky for all of us, help is just a key press away. Yes, literally one key press — just press the F1 key. Try it now.

This starts up the Help system. From there you can search on a keyword or browse through the Help Table of Contents. Figure 1-10 shows how the help system was browsed through to find some specific help. Way on the right is the Help Table of Contents from which a specific help topic is selected and displayed.

Later on when you are working with Excel functions, you can get help on specific functions directly by clicking the Help with This Function link in the Insert Function dialog box. Chapter 2 covers the Insert Function dialog box in detail.

Figure 1-10:

Displaying Help.

Gaining the Upper Hand on Formulas

Okay, get to the nitty gritty of what Excel is all about. Sure, you can just enter data and leave it as is, and even generate some pretty charts from it. But getting answers from your data, or creating a summary of your data, or applying what-if tests — all of this takes formulas.

To be specific, a formula in Excel calculates something, or returns some result based on data in the worksheet. Formulas are placed in cells and must start with an equal sign (=) to tell Excel that it is a formula and not data. Sounds simple, and it is.

Look at some very basic formulas. Table 1-2 shows a few formulas and tells you what they do.

We use the word “return” to refer to what displays after a formula or function does its thing. So to say “the formula returns a 7″ is the same as saying “the formula calculated the answer to be 7.”

| Table 1-2 | Basic Formulas |

| Formula | What It Does |

| =2 + 2 | Returns the number 4. |

| =A1 + A2 | Returns the sum of the values in cells A1 and A2, whatever |

| those values may be. If either A1 or A2 has text in it, then an | |

| error is returned. | |

| = D5 | The cell that contains the formula ends up displaying the |

| same value that is in cell D5. If you try to enter this formula | |

| into cell D5 itself, you create a condition called a circular | |

| reference. That is a no-no. You can read more about circular | |

| references in Chapter 4. | |

| =SUM(A2:A5) | Returns the sum of the values in cells A2, A3, A4, and A5. |

| Recall from above the syntax for a range. This formula uses | |

| the SUM function to sum up all the values in the range. |

Entering your first formula

Ready to enter your first formula? Make sure Excel is running and a worksheet is in front of you, and then:

1. Click an empty cell.

2. Type this in: = 10 + 10.

3. Press Enter.

That was easy, wasn’t it? You should see the result of the formula — the number 20.

Try another. This time you create a formula that adds together the value of two cells:

1. Click a cell (any cell will do).

2. Type in a number.

3. Click another cell.

4. Type in another number.

5. Click a third cell. This cell contains the formula.

6. Type in an equal sign (=).

7. Click the first cell.

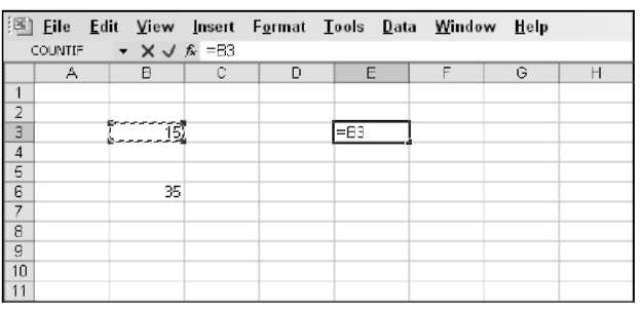

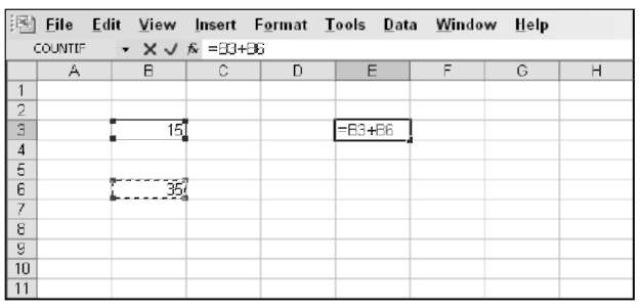

This is an important point in the creation of the formula. What is happening now is that the formula is being written by both your keyboard entry and clicking around with the mouse. The formula should now look about half complete. The formula should now be an equal sign immediately followed by the address of the cell you just clicked. Figure 1-11 shows what this looks like.

Figure 1-11:

Entering a formula that references cells.

In the example, the value 15 has been entered into cell B3 and the value 35 into cell B6. The formula was started in cell E3. Cell E3 so far has =B3 in it.

8. Enter a plus sign (+).

9. Click the cell that has the second entered value.

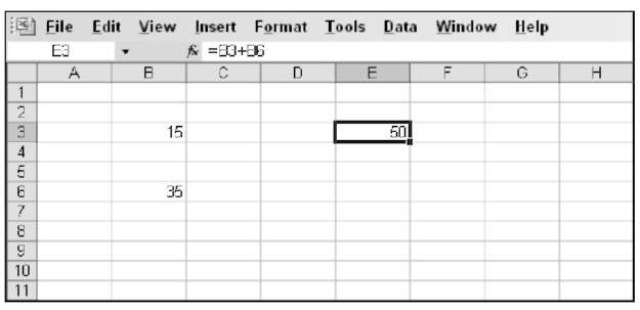

In our example, this is cell B6. The formula in cell E3 now looks like this: =B3 + B6. You can see this is Figure 1-12.

Figure 1-12:

Completing the formula.

10. Press Enter. This ends the entry of the function. All done! Congratulations!

Figure 1-13 shows how our example ended up. Cell E3 displays the result of the calculation. Also notice that the Formula bar displays the contents of cell E3, which really is the formula.

Figure 1-13:

A finished formula.

Understanding references

References abound in Excel formulas. You can reference cells. You can reference ranges. You can even reference cells and ranges on other worksheets. You can reference cells and ranges in other workbooks. Formulas and functions are at their most useful when using references, so you need to understand them.

And if that isn’t enough to stir the pot, you can use three types of cell references: relative, absolute, and mixed. Okay, one step at a time here. We can get to it all.

Try out a formula that uses a range. Formulas that use ranges often have a function in the formula, so use the SUM function here:

1. Enter some numbers in a group of cells going down one column.

2. Click in another cell where you want the result to appear.

3. Enter =SUM( to start the function.

4. Click the first cell that has an entered value, and while holding the left mouse button down, drag the mouse pointer over all the cells that have the entered values.

You should see the range address appear where the formula and function are being entered.

5. Enter a closing parenthesis.

6. Press Enter to end the function entry.

Give yourself a pat on the back!

Wherever you drag the mouse to enter the range address into a function, you can also just type in the address of the range, if you know what it is.

Excel is dynamic when it comes to cell addresses. If you have a cell with a formula that references a cell address, and you copy the formula to another cell, the address of the reference inside the formula changes. Excel updates the reference inside the formula to match the number of rows and/or columns that separate the original cell (where the formula is being copied from) from the new cell (where the formulas is being copied to). This may be confusing so look at an example so you can see this for yourself:

1. In cell B2, enter 100.

2. In cell C2, enter this: =B2 * 2.

3. Press Enter.

Cell C2 now returns the value 200.

4. If C2 is not the active cell, click it once.

5. Copy the cell.

You can choose Edit O Copy from the menu, or press Ctrl+C on the keyboard.

6. Click cell C3.

7. To paste, choose Edit O Paste from the menu, or press Ctrl+V on the keyboard.

8. If you see a strange moving line around cell C2, just press the ESC key on the keyboard to make it stop.

Did you see a moving line stay over cell C2? That’s called a marquee. It’s a reminder that you are in the middle of a cut or copy operation, and the marquee goes around the cut or copied data.

Cell C3 should now be the active cell, but if it is not, just click it once. Look at the formula bar. The contents of cell C3 is =B3 * 2 and not the =B2 * 2 that you copied.

What happened? Excel, in its wisdom, assumed that if a formula in cell C2 references the cell B2 — one cell to the left, then the same formula put into cell C3 is supposed to reference cell B3 — also one cell to the left.

When copying formulas in Excel, relative addressing is usually what you want. That’s why it is the default behavior. Sometimes you do not want relative addressing but rather absolute addressing. This is making a cell reference fixed to an absolute cell so that it does not change when the formula is copied.

In an absolute cell reference, a dollar sign ($) precedes both the column letter and the row number. You can also have a mixed reference in which the column is absolute and the row is relative or vice versa. Here’s a summary of this. To create a mixed reference, you use the dollar sign in front of just the column letter or row number. Here are some examples:

| Reference Type | Formula | What happens when you copy the formula |

| Relative | =A1 | Either, or both, the column letter A and the row number 1 can change. |

| Absolute | = $A$1 | The column letter A and the row number 1 won’t change. |

| Mixed | = $A1 | The column letter A won’t change. The row number 1 can change. |

| Mixed | =A$1 | The column letter A can change. The row number 1 won’t change. |

Copying formulas with the fill handle

As long as we’re on the subject of copying formulas around, take a look at the fill handle. You’re gonna love this one! The fill handle is a quick way to copy the contents of a cell to other cells with just a single click and drag.

The active cell always has a little square box in the lower-right side of its border. That is the fill handle. When you move the mouse pointer over the fill handle, the mouse pointer changes shape. If you click and hold down the mouse button, you can now drag up, down, or across over other cells. When you let go of the mouse button the contents of the active cell automatically copy to the cells you dragged over.

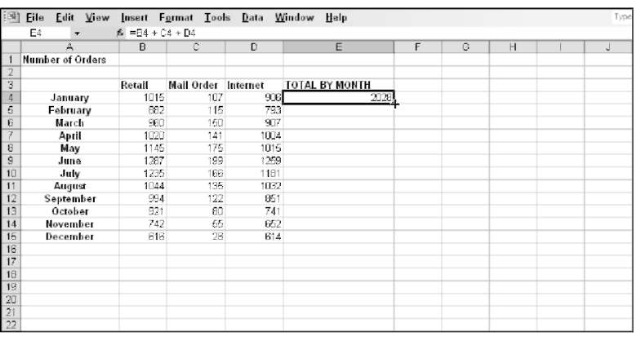

A picture is worth a thousand words, so take a look. Figure 1-14 shows a worksheet that adds some numbers. Cell E4 has this formula: =B4 + C4 + D4. This formula needs to be placed in cells E5 through E15. Look closely at cell E4. The mouse pointer is over the fill handle and it has changed to what looks like a small black plus sign. We are about to use the fill handle to drag that formula to the other cells.

Figure 1-14:

Getting ready to drag the formula down.

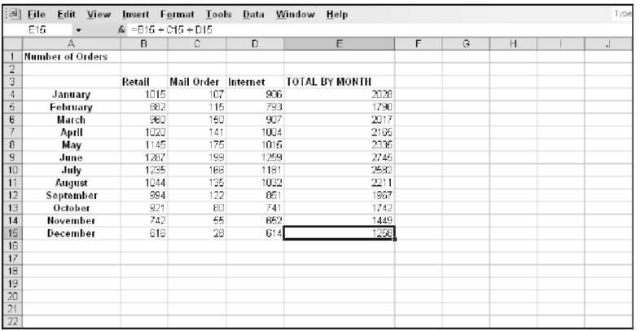

Figure 1-15 shows what the worksheet looks like after the fill handle is used to get the formula into all the cells. This is a real timesaver. Also you can see that the formula in each cell of column E correctly references the cells to its left. This is the intention of using relative referencing. For example, the formula in cell E15 ended up with this formula: =B15 + C15 + D15.

Figure 1-15:

Populating cells with a formula by using the Fill Handle.

Assembling formulas the right way

There’s a saying in the computer business — garbage in, garbage out. And that applies to how formulas are put together. If a formula is constructed the wrong way, it either returns an error or an incorrect result.

Two types of errors can occur in formulas. In one type, Excel can calculate the formula but the result is wrong. On the other type, Excel is not able to calculate the formula. Check out both of these.

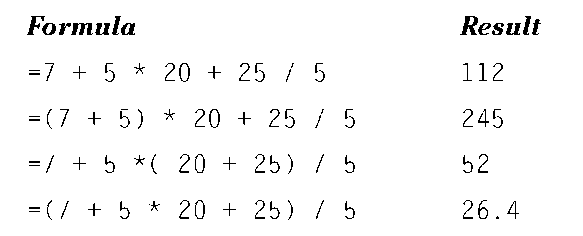

A formula can work and still produce an incorrect result. Excel does not report an error because there is no error for it to find. This is almost always the result of not using parentheses properly in the formula. Take a look at some examples:

All of these are valid formulas but the placement of parentheses makes a difference in the outcome. You must take into account the order of mathematical operators when writing formulas. The order is:

1. Parentheses

2. Exponents

3. Multiplication and division

4. Addition and subtraction

This is a key point of formulas. It is easy to just accept a returned answer. After all, Excel is so smart. Right? Wrong! Like all computer programs, Excel can only do what it is told. If you tell it to calculate an incorrect but structurally valid formula, it will do so. So watch your Ps and Qs! Er, rather your parentheses and mathematical operators when building formulas.

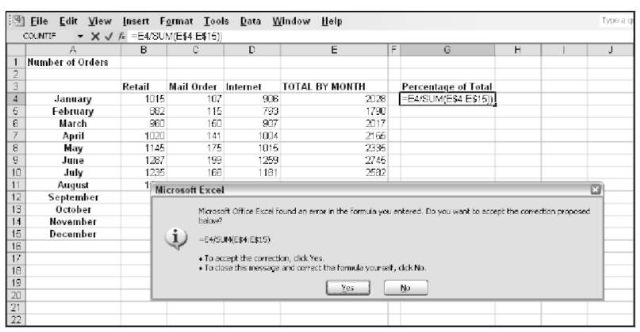

The second type of error is when there is a mistake in the formula or in the data the formula uses that prevents Excel from calculating the result. Excel makes your life easier by telling you when such an error occurs. To be precise:

Excel displays a message when you attempt to enter a formula that is not constructed correctly.

Excel returns an error message in the cell when there is something wrong with the result of the calculation.

First, let’s see what happened when we tried to finish entering a formula that had the wrong number of parentheses. Figure 1-16 shows this.

Figure 1-16:

Getting a message from Excel.

Excel finds that there is an uneven number of open and closed parentheses. Therefore the formula cannot work (it does not make sense mathematically) and Excel tells you so. Watch for these messages, they often offer a solution.

On the other side of the fence are errors in returned values. If you got this far, then the formulas syntax passed muster, but something went awry nonetheless. Possible errors are:

Attempting to perform a mathematical operation on text Attempting to divide a number by 0 (that’s a mathematical no-no) Trying to reference a non-existent cell, range, worksheet, or workbook Entering the wrong type of information into an argument function

This is by no means an exhaustive list of possible error conditions, but you get the idea. So what does Excel do about it? There are a handful of errors that Excel places into the cell with the problem formula. These are:

| Error Type | When it happens |

| #DIV/0! | When trying to divide by 0 |

| #N/A! | When a formula or a function inside a formula |

| cannot find the referenced data | |

| #NAME? | When text in a formula is not recognized |

| #NULL! | When a space was used instead of a comma in for- |

| mulas that reference multiple ranges (A comma is | |

| necessary to separate range references.) |

| Error Type | When it happens |

| #NUM! | When a formula has numeric data that is not valid |

| for the type of operation | |

| #REF! | When a reference is not valid |

| #VALUE! | When the wrong type of operand or function |

| argument is used |

Chapter 4 discusses catching and handling formula errors in detail.

Using Functions in Formulas

Functions are like little utility programs that do a single thing. For example, the SUM function sums up numbers, the COUNT function counts, and the AVERAGE function calculates an average.

There are functions to handle many different needs: working with numbers, working with text, working with dates and times, working with finance, and so on. Functions can be combined and nested (one goes inside another). Functions return a value, and this value can be combined with the results of a formula. The possibilities are nearly endless.

But functions do not exist on their own. They are always a part of a formula. Now that can mean that the formula is made up completely of the function or that the formula combines the function with other functions, data, operators, or references. But they must follow the formula golden rule: Start with the equal sign. Look at some examples.

| Function/Formula | Result |

| =SUM(A1:A5) | Returns the sum of the values in the |

| range A1:A5. This is an example of a | |

| function serving as the whole formula. | |

| =SUM(A1:A5) /B5 | Returns the sum of the values in the |

| range A1:A5 divided by the value in | |

| cell B5. This is an example of mixing a | |

| function’s result with other data. | |

| =SUM(A1:A5) + AVERAGE(B1:B5) | Returns the sum of the range A1:A5 |

| added with the average of the range | |

| B1:B5. This is an example of a | |

| formula that combines the result | |

| of two functions. |

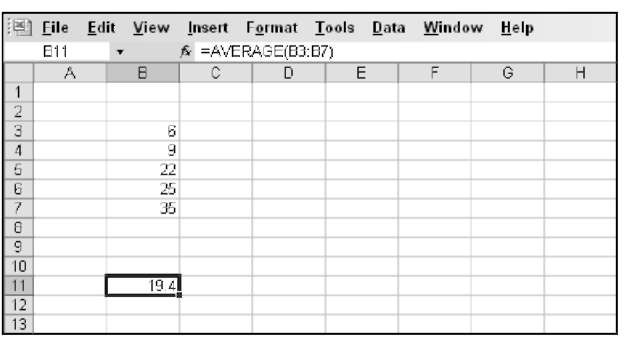

Ready to write your first formula with a function in it? Let’s go! This function creates an average. Here’s what you do:

1. Enter some numbers in the cells of a column.

2. Click an empty cell where you want to see the result.

3. Enter =AVERAGE( to start the function.

4. Click the first cell with an entered value and then while holding the mouse button down, drag the mouse pointer over the other cells that have values.

An alternative to this is to just enter the range of those cells.

5. Enter a closing parenthesis to end the function.

6. Press Enter.

Wonderful! If all went well, your worksheet should look a little bit like ours, in Figure 1-17. Cell B11 has the calculated result, but look up at the formula bar and you can see the actual function as it was entered.

Figure 1-17:

Entering the AVERAGE function.

Formulas and functions are dependent on the cells and ranges to which they refer. If you change the data in one of the cells, the result returned by the function updates. You can try this now. In the example you just did with making an average, click into one of the cells with the values and enter a different number. The returned average changes.

A formula can consist of nothing but a single function — preceded by an equal sign, of course!

Looking at what goes into a function

Most functions take inputs, called arguments, that specify the data the function is to use. (Another term for arguments is parameters.) Some functions take no arguments, some take one, and others take many — it all depends on

the function. The argument list is always enclosed in parentheses following the function name. If there’s more than one argument, they are separated by commas. Look at a few examples:

| Function | Comment |

| =NOW() | Takes no arguments. |

| =AVERAGE(A6,A11,B7) | Take up to 30 arguments. Here, |

| three cell references are | |

| included as arguments. The argu- | |

| ments are separated by commas. | |

| =AVERAGE(A6:A10,A13:A19,A23:A29) | Arguments are range references |

| instead of cell references. The | |

| arguments are separated by | |

| commas. | |

| =IPMT(B5, B6, B7, B8) | Requires four arguments. |

| Commas separate the arguments. |

Some functions have required arguments and optional arguments. You must provide the required ones. The optional ones are well, optional. But you may want to include them if their presence helps the function return the value you need.

The IPMT function is a good example. Four arguments are required and two more are optional. You can read more about the IPMT function in Chapter 5. You can read about function arguments in general in Chapter 2.

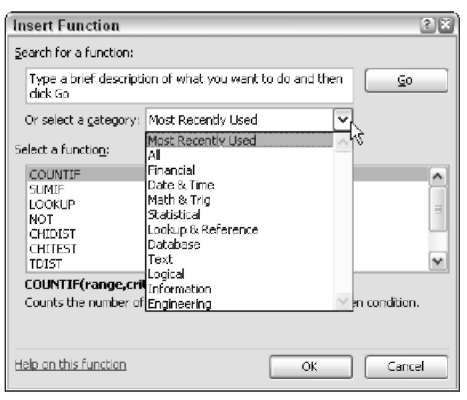

Discovering usages of a function’s arguments

Memorizing the arguments that every function takes would be a daunting task. We can only think that if you could pull that off you could be on television. But back to reality, you don’t have to memorize them because Excel helps you select what function to use, and then tells you which arguments are needed.

Figure 1-18 shows the Insert Function dialog box. This great helper is accessed by choosing Insert O Function from the menu. The dialog box is where you select a function to use.

The dialog box contains a listing of all available functions — and there are a lot of them! So to make matters easier, the dialog box gives you a way to search for a function by a keyword, or you can filter the list of functions by category.

Figure 1-18:

Using the Insert Function dialog box.

Try it out! Here’s an example of how to use the Insert Function dialog box to multiply together a few numbers:

1. Enter three numbers in three different cells.

2. Click an empty cell where you want the result to appear.

3. Choose Insert O Function from the menu to open the Insert Function dialog box.

As an alternative, you can just click the little fx button on the Formula bar.

4. In the dialog box, select All or Math & Trig as the category.

5. In the list of functions, find and select the PRODUCT function.

6. Click the OK button.

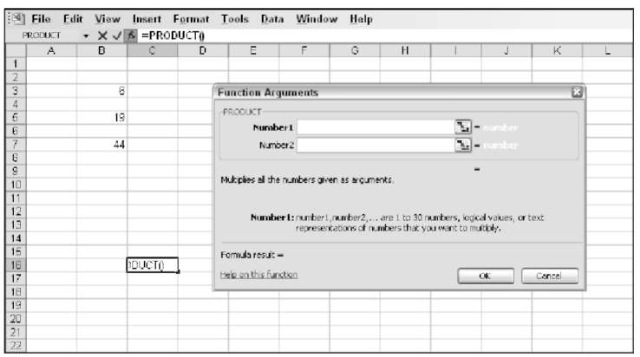

This closes the Insert Function dialog box and now displays the Function Arguments dialog box. See Figure 1-19.

Figure 1-19:

Getting ready to enter some arguments to the function.

You can use the Function Arguments dialog box to enter as many arguments as needed. Initially it might not look like it can accommodate enough arguments. We need to enter three, but it looks like there is only room for two. This is like musical chairs!

More argument entry boxes appear as you need them. First though — how do you enter the argument? There are two ways. You can type in the numbers or cell references into the boxes, or you can use those funny looking squares to the right of the entry boxes. In Figure 1-19 there are two entry boxes ready to go. To the left of them are the names Number 1 and Number 2. To the right of the boxes are the little squares.

These squares are actually called RefEdit controls. They make argument entry a snap. All you do is click one, then click the cell with the value, and press Enter. To continue:

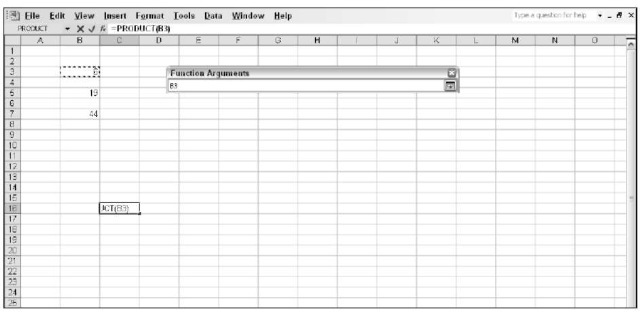

7. Click the RefEdit control to the right of the Number 1 entry box.

The Function Arguments dialog box shrinks to just the size of the entry box.

8. Click the cell with the first number.

Figure 1-20 shows what the screen looks like at this point.

Figure 1-20:

Using RefEdit to enter arguments.

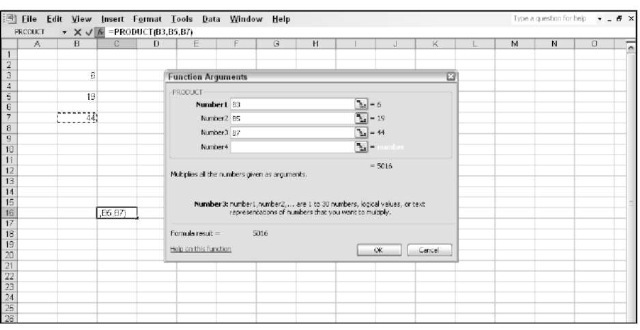

9. Press Enter.

The Function Arguments dialog box reappears with the argument entered into the box. The argument is not the value in the cell, but instead is the address of the cell with the value — exactly what you want.

10. Repeat Steps 7-9 to enter the other two cell references.

Figure 1-21 shows what the screen should now look like.

Figure 1-21:

Completing the function entry.

11. Click OK or just press Enter to complete the function.

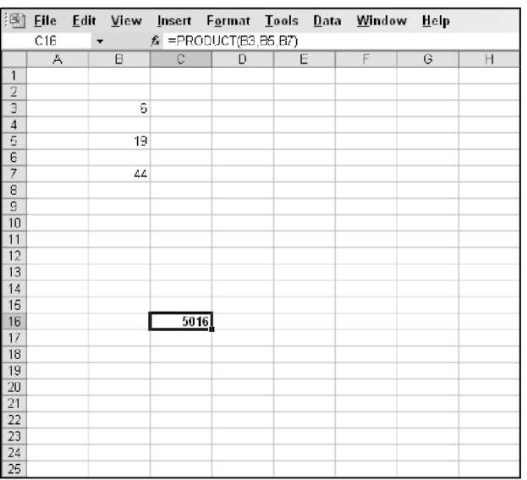

Figure 1-22 shows the result of all this hooplah. The PRODUCT function returns the result of the individual numbers being multiplied together.

Figure 1-22:

Math was never this easy!

You do not have to use the Insert Function dialog box to enter functions into cells. It is there for convenience. As you become familiar with certain functions that you use repeatedly, you may find it faster to just type the function directly into the cell.

Nesting functions

Nesting is something a bird does, isn’t it? Well, a bird expert would know the answer to that one but we do know how to nest Excel functions. A nested function is a function that is tucked inside another function — as one of its arguments. Nesting functions let you returns results you would have a hard time getting to otherwise.

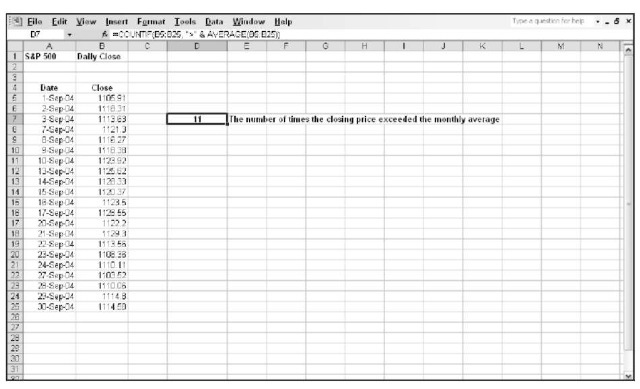

Figure 1-23 shows the daily closing price for the S&P 500, for the month of September 2004. A possible analysis is to see how many times the closing price was higher than the average for the month. Therefore the average needs to be calculated first, before any single price can be compared. By embedding the AVERAGE function inside another function, the average is first calculated.

When a function is nested inside another, the inner function is calculated first. Then that result is used as an argument for the outer function.

Figure 1-23:

Nesting functions.

The COUNTIF function counts the number of cells in a range that meet a condition. The condition is that any single value in the range is greater than (>) the average of the range. The formula in cell D7 is:

![]()

The average function is evaluated first, and then the COUNTIF function is evaluated using the returned value from the nested function as an argument.

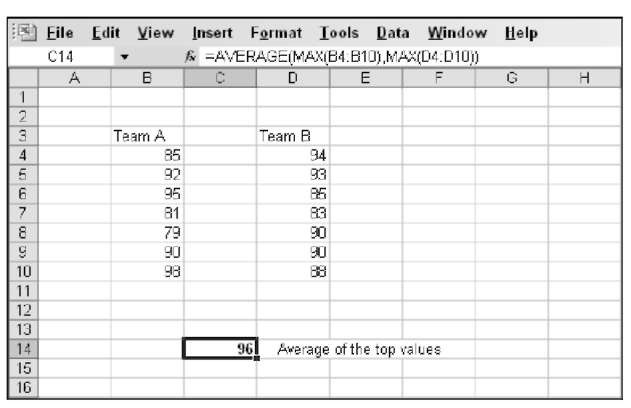

Nested functions are best entered directly. The Insert Function dialog box does not make it easy to enter a nested function. Try one out. In this example, you use the AVERAGE function to find the average of the largest values from two different sets of numbers. The nested function in this example is MAX. You enter the MAX function twice within the AVERAGE function:

1. Enter a few different numbers in one column.

2. Enter a few different numbers in a different column.

3. Click empty cell where you want the result to appear.

4. Enter =AVERAGE( to start the function entry.

5. Enter MAX(.

6. Click the first cell in the first set of numbers and drag over all the cells of the first set.

The address of this range enters into the MAX function.

7. Enter a closing parenthesis to end the first MAX function.

8. Enter a comma Q.

9. Once again, enter MAX(.

10. Click the first cell in the second set of numbers.

Keep the mouse button pressed and drag over all the cells of the second set. The address of this range enters into the MAX function.

11. Enter a closing parenthesis to end the second MAX function.

12. Enter another closing parenthesis.

This one is to end the AVERAGE function.

13. Press Enter.

Figure 1-24 shows the result of our nested function. Cell C14 has this formula:

![]()

When using nested functions, the outer function is preceded with an equal sign if it is the beginning of the formula. Any nested functions are not preceded with an equal sign.

Nested functions are used in examples in various places in the topic. The COUNTIF, AVERAGE, and MAX functions are discussed in Chapter 9.

You can nest functions up to seven levels.

Figure 1-24:

Getting a result from nested functions.

Using array functions

Some functions return an array of data. An array is a collection of related data. The output of an array function goes into multiple cells. To make this happen, the function entry must follow a specific protocol, which we describe soon.

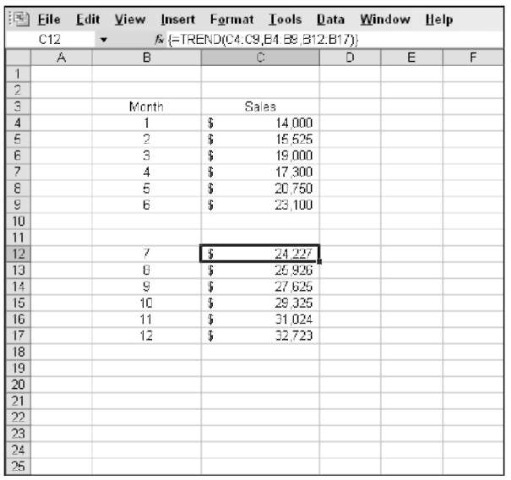

Figure 1-25 shows an example. In this worksheet, you have data on income for months 1-6 and want to estimate what income will be for months 7-12 based on this data. The TREND function, which is an array function, is designed for just this task. We walk you through this example.

You must remember two details when using an array function:

You start by selecting the range of cells where the array of results is

to go.

You enter the function in the usual way, but you must complete entry by holding down the Ctrl and Shift keys while you press Enter.

When you enter an array formula in this way, Excel knows it is an array formula and displays the results correctly. It won’t work if you enter the formula by pressing Enter alone.

Selecting the number of cells required to receive a returned value begins entry of array functions. Entry of array functions is completed with the special Ctrl + Shift + Enter keystroke.

Figure 1-25:

Viewing a trend returned with the TREND array function.

Here’s how to enter and complete the array function demonstrated in Figure 1-25:

1. Near the top of one column, enter the header “Month”. In the next column to the right, in the same row, enter the header “Sales”.

2. Under the Month header, enter the numbers 1 through 6, one number in each successive row.

3. Skipping one row, enter the numbers 7 through 12 going down through the column.

4. Under the Sales header, enter numeric values, such as those seen in Figure 1-25: 14,000; 15,525; 19,000; 17,300; 20,750; and 23;100.

You can enter other values if you want.

5. At this point, the worksheet is set up with all the initial values needed to use the TREND function.

The TREND function is used to estimate the sales for months 7 through 12. It does this by evaluating a pattern from the first six months of values.

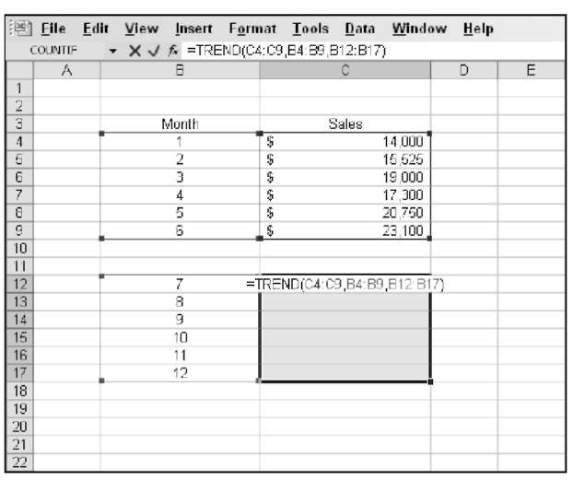

6. Select the cells adjacent to the months numbered 7 through 12.

7. Enter =TREND( to start the function.

8. Click the cell that has the sales for month number 1 in it, keep the mouse button pressed, and drag down through the other sales amounts.

9. Enter a comma Q

10. Click the cell that has the month number 1 in it, keep the mouse button pressed, and drag down through month number 6.

11. Enter a comma(,).

12. Click the cell that has the month number 7 in it, keep the mouse button pressed, and drag down through month number 12.

13. Enter a closing parenthesis.

Figure 1-26 shows what the worksheet should now look like. Notice that although entry appears to be going into one cell, all the selected cells receive a value when the entry is completed.

Figure 1-26:

Completing the array function entry.

14. Last but not least — do not press Enter to complete the entry. Press

Ctrl+Shift+Enter. Go for it!

And that’s it! You now see the anticipated sales for months 7 through 12. This “trend” is based on an inherent trend found in the known values of the first six months.

Array functions are a bit confusing but mighty powerful. Chapter 3 is devoted to array formulas and functions. Chapter 11 discusses the TREND function.