Abstract

As energy service companies move beyond their traditional markets, technical competence must be combined with other skills, such as an understanding of different types of institutions and the ability to work with individuals of varying backgrounds and even cultures. In the United States, Tribal communities are one such market. This paper discusses important factors beyond engineering and economics that should be considered when working with Tribal communities, and presents an overview of experiences and recommendations for successful projects. Although the focus is on Tribal communities, the conclusions drawn are also applicable to rural communities and to projects in countries other than the United States— particularly those in developing countries where cultural traditions remain strong and energy service companies are as yet uncommon.

INTRODUCTION

The traditional markets for energy efficiency services are institutional customers, educational institutions of all kinds, and government entities—all institutions with large facilities having high utility bills, significant air handling requirements, and a reasonably uniform building configuration. As one moves outside these traditional markets to those that have historically been underserved, however, life can become both more complicated and more interesting for the energy service provider.

High on the list of underserved markets are facilities in developing countries and (inside the United States) rural and Tribal facilities, which provide challenges that are technical, operational, and above all cultural. To succeed in these types of projects, a company must include cultural considerations in its project implementation. The authors, with experience in implementing projects successfully in these varied environments, present projects on Tribal lands as a model for some of the approaches needed to accomplish energy efficiency programs in these areas.

As Tribal governments and communities gain and establish control of their natural resources, economies, and communities, they are faced with the challenges of developing and maintaining not only skilled labor pools, but also Tribal infrastructure and even sustainable economies. Often, all rural communities—and Tribal communities in particular—must perform and maintain necessary community services such as law enforcement, health services, and government functions. With the limited number of people in these areas, this can mean that opportunities for economic growth fall by the wayside.

Communications technologies and widespread travel are among the trends causing the world to shrink, so that communities that have until now been considered out of the mainstream are turning to urban resources and businesses to gain more knowledge and obtain services that will introduce them to new technologies, improve economic sustainability, and empower local government officials. For service companies working with these communities, it is important to remember that technology and engineering expertise may take a back seat to knowledge, understanding, and awareness of the community’s culture. Working with Tribal governments and communities presents technical challenges, of course—but more important are the challenges of cultural differences and geographic location.

ENERGY EFFICIENCY ON TRIBAL LANDS

Background

There are more than 500 federally recognized Tribes in the United States. There are reservations in almost every state, and they range in size from less than one acre to many thousands of square miles, from cities to forests to beaches to deserts. The Tribes themselves are extremely varied, with different histories, cultures, languages, religions, and traditions. The United States recognizes the right of these Tribes to self-government and supports their Tribal sovereignty and self-determination. This means that each Federally recognized Tribe possesses the right to form its own government, to develop and enforce its own laws, to tax, and exclude persons from Tribal territories, among other rights and responsibilities.

As a side note, it is often believed that, with the advent of Indian Gaming Laws that allow casinos on Tribal lands, all Tribes have adopted this approach to economic development and, therefore, are highly developed and profitable enterprises in themselves. But like all generalizations, this one is incorrect. Many Tribes have resisted gaming for cultural or other reasons, and even where gaming is present, the methods of distributing economic benefits vary widely.

In 2005 and 2006, a series of energy efficiency audits was performed on residential and commercial buildings located on Tribal lands. Under a U.S. Department of Energy grant directed by the Council for Energy Resource Tribes (CERT) based in Denver, Colorado, the purposes of the energy audits were to identify energy conservation opportunities for the Tribes and to establish alliances between teams of private experts and Tribes to develop energy efficiency.

The energy audits were performed on Tribal lands located in California, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and South Dakota by a team consisting of Indian and non-Indian personnel. The team traveled to the Tribal communities and worked closely with Tribal leaders and community members to identify areas that would improve the energy efficiency of the buildings. The results and recommendations were summarized in each case in a report, with copies submitted to Tribal leaders for future implementation.

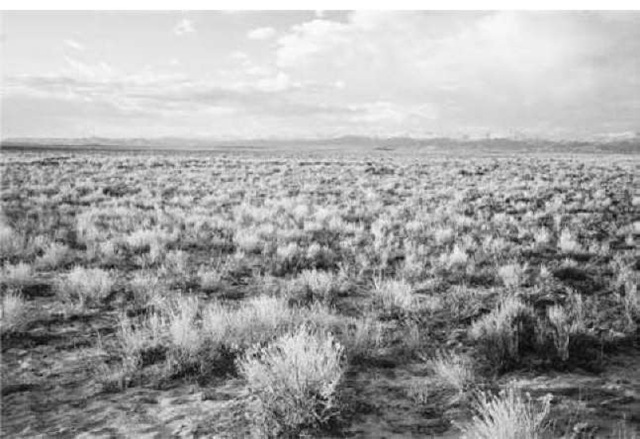

The recommendations and scenarios discussed in this paper are based on the observations and experiences drawn from the performance of these energy audits on Tribal lands. The challenges the Tribal communities face with regard to geographic location, access to information, lack of access to subject-matter experts, and cultural awareness are similar to those faced by any small rural community in the United States—although the cultural gap can be wider (Fig. 1).

Tribal Governments

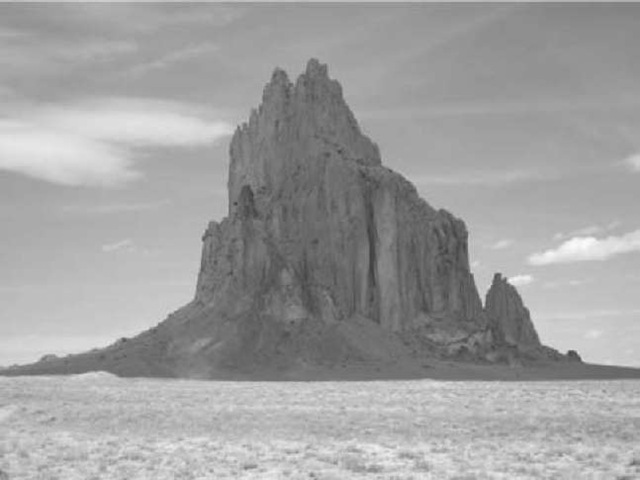

Like many small rural communities, Tribal communities are often too small to be considered cities. Instead, as small towns and villages, they usually entrust government and community decisions to an elected board, council, or chapter, which may be made up of commissioners, community elders, or volunteers. Frequently, as in small towns, the positions are part time (though with full-time responsibility), and usually, a president, chairperson, or mayor functions as the chief executive officer. Naturally, in smaller communities such as these, the holding of political office is not a career path, but something one does on the side, as an obligation to the community or as a family responsibility, after achieving a good reputation in another field (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 Cultural and geographic challenges can be enormous in the open rural areas of the West. Where distances are so vast, the sense of community becomes doubly important.

With such a small governing council or board managing a small community where few resources are available, and with both limited funding and time, the primary goal of the board usually is meeting the most critical needs of the community. These include water supply, law enforcement, fire protection, health services, and the school system. Therefore, when opportunities arise for changes that may bring economic growth (energy efficiency improvements, capacity building in the energy arena, and renewable energy projects, for example), the community may have difficulty assessing the opportunities. The first issue here is the lack of a base of shared understanding such as that developed in larger cities by, for example, public relations and advertising campaigns; followed by a lack of skilled community experts, the inadequacy of funding, and generally insufficient or inaccurate information. These community challenges require the Tribes to rely on outside resources to fill these voids and provide community opportunities. Evidently, therefore, there is a great possibility for service providers to work with Tribal communities—but it is important first to learn to think outside the traditional “energy service company” box. When working with Tribal communities, businesses must first gain a sense of understanding of the culture, the community and its priorities, and the way that particular government works. Only in this way will any project be successful and lead to future work in the community.

Fig. 2 In Tribal communities, people, places, and other components of the world are often given more respect than is true in the urban culture. “Shiprock” on the Navajo Reservation.

Observations

Cultural Awareness

As noted in the Background section earlier in this chapter, each Tribal community is different, with its own cultural values and traditions. In the context of developing and implementing a project, these differences in turn lead to differences in decision-making, leadership styles, and other business-related characteristics. It is important to understand that what may be observed in one village may not be valued in another. One must observe, learn, respect, and acknowledge the customs and values of each Tribal community.

A few general comments can be made, however, to highlight the types of situations and sensitivities of which any company operating on Tribal lands should be aware. These are not meant to be typical, as there is no such thing, but they are indicative.

It is not uncommon, for example, when working with Tribal communities that meetings be opened with a blessing/prayer led by a community leader or elder before any introductions and certainly before the business part of the meeting can start. When introductions begin, the focus is not on one’s own individual accomplishments, but on one’s family, heritage, and connection to the community. This stems from the importance of humility in many Indian cultures. Each person is considered to be equal to the others and no better. Therefore, in working with small Tribal communities, it is important to be humble and to focus importance on the Tribal elders, council members, and community members. Those who present a sense of their own importance or take themselves too seriously may violate Tribal cultural values and might be considered untrustworthy by the community.

Another common issue for those who have not worked with Tribal communities is that they must also understand the culture’s ways of showing respect for another person. If, during a presentation to the community, the presenter does not see the direct eye contact to which he or she is accustomed, which in urban business culture usually means that the audience is involved, he or she should not feel as though the audience is disinterested in the topic at hand. In many Native American cultures, indirect eye contact may be considered a sign of respect.

Probably the most misunderstood value of American Indian culture (and the cultures of many developing countries) is the meaning of time. For one working with Tribal communities, patience and understanding of the meaning of time are of vital importance. In many American Indian cultures, time is not measured by the clock, but by when the situation feels appropriate. In many instances, Tribal community meetings may run late into the night or may not begin until all appropriate people are present. As in any small community where relationships are more important than deadlines, the necessity of dealing with daily issues may delay Tribal leaders; their commitment to the community is paramount, however, and resolutions of any local issues must be addressed. Everywhere in the world, the rhythms of small-community life are different—not necessarily more relaxed, as the workloads of these local leaders often put those of corporate chiefs to shame—and have a different focus. It is the community that is important. Therefore, service providers should be prepared to wait, if need be, and to change their schedules based on unforeseen circumstances. On the other hand, they should not take this as an excuse to be late themselves; that would be a strong sign of disrespect.

While working on Tribal lands, it is not uncommon to encounter elders and/or Tribal members who speak their native language as their primary language. While performing the energy audits, we had the opportunity to perform an energy audit on the home of an elderly Tribal couple not fluent in English. As in all the audits, a preaudit interview with the occupants was performed to gain a better understanding of energy usage in the home. During the interview, an interpreter was utilized. This situation also provided the team the opportunity to learn a few words in the local language. Most important was “Thank you”—a phrase that was returned with a smile at the end of the interview. Such opportunities should be appreciated, as they provide insight into the culture, show interest and respect, and provide to energy efficiency work a spice and flavor that are not often found in an office building or a hospital.

These examples are neither typical nor exhaustive, of course; with so many different cultures and so many different communities, it would be impossible for them to be so. If service providers are interested, genuine, respectful, and quietly professional, and if they watch and listen for cues from those around them, cultural awareness will develop.

Sense of Community

Business culture is often modeled on the culture of a big city—fast-paced, goal-oriented, with one-dimensional relationships and a separation between professional and personal life. Rural communities, including Tribal ones, are the centers of small-town life—even now, in the 21st century. Community life is important; relationships are of long standing; decisions are often made for reasons that are difficult for those from outside the community to understand; and discussions often appear to go back generations.

To work in such places, this sense of community must be understood and appreciated, and any projects must enhance that community to be successful. In addition, the traditional small-town value of “My word is my bond” is alive and strong in small towns and Tribal lands. When working in a community that has a shared memory going back for generations, it is important for service providers to say what they will do—and do what they say. Trust, which develops slowly in communities that are inherently wary of outsiders, is critical for success.

The clan system prevalent in the American Indian culture makes the community, in essence, a circle of family. This circle provides community members a sense of family support and a strong set of relationships. When accepted into this family, an outside service provider may be expected to assist the community in areas outside the project objectives, such as locating sources of information for the Tribal communities. In a community, boundaries are fluid, and when one joins the community, those fluid boundaries surround everyone.

Long-Term Orientation

In Tribal communities, an issue related to both the sense of community and the sense of time mentioned earlier is the long-term orientation taken to decision-making and project implementation. For most service providers, the process of proposing a project, having it accepted, and then implementing it is most familiar—and preferred. In Tribal communities, that process is often broken down into multiple steps on a time scale that is defined by other constraints, such as the needs of the community, Tribal leaders’ lack of time, or insufficient funding. When a Tribal leader agrees that it is a good idea to implement a project, it is tempting to assume that he or she means now, or at least within the next few months. Unfortunately, the real meaning may be (as mentioned earlier) “when the time is right”—by which time the service provider may have given up and moved on to other projects.

It is important, therefore, for each party to understand the other’s time scales and the steps that must be taken to move the project along one step at a time (with the associated approximate costs of those steps).

Geographic Location and Coordination

With an audit team of six, transporting equipment and personnel to each Tribal community required significant planning and preparation for each energy audit to be effective, successful, and within budget guidelines. On average, travel entailed one full day of travel by car to reach the sites, with three days on-site performing the energy audits.

To ensure that each trip was successful, documentation on energy usage pertaining to each building was requested in advance; meetings were scheduled; and a Tribal community point of contact was established, most often a Tribal leader. Because time runs differently in most American Indian cultures, this preparation required persistence and patience, as well as understanding. The possibility presented by using energy efficiency programs to bring new technology and opportunities to the community may be overridden by other daily priorities. We discovered that where possible, it was good to include the possibility of staying one extra day, just in case the schedule was changed during the course of the audit. (We always used that extra time).

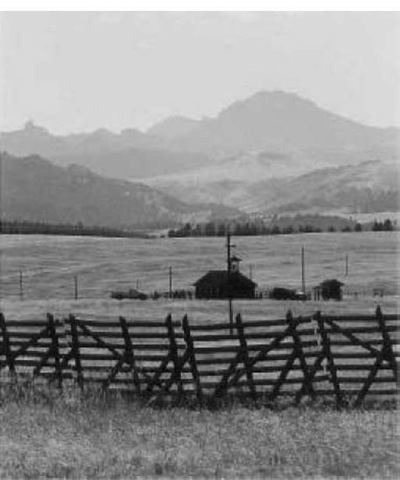

Unlike most cities, where business representatives have the capability to travel to and from clients and conduct business in one day, rural areas and Tribal locations usually must be the single focus for that day or for several days. Therefore, additional planning, patience, and persistence play an important role (Fig. 3).

Technical Issues

In a standard commercial building, a school, or a hospital, the contact person for the energy audit is likely to be an engineer, an energy manager, or a technician familiar with the equipment in that particular building. In Tribal communities, there certainly are some such individuals, but it is the norm that those responsible for energy issues, construction, and maintenance also have significant other responsibilities. Given that situation, it is simply not possible for these individuals—no matter how dedicated and professional they may be—to be familiar with the opportunities provided by energy efficiency audits and enhancements. Neither is it often appropriate to recommend the latest, fanciest equipment unless the staff will be effectively trained on it and unless it can be serviced throughout its life.

Fig. 3 In rural and Tribal areas, a “community” often consists of a very few buildings in large land areas.

As engineers, we are trained to recommend the best alternatives. On Tribal lands and in rural communities, however, the best technical solution may not be the best all-around solution. Cultural concerns, experience levels, power availability and reliability, time available for maintenance, training needs, service availability, and many other such factors must be taken into consideration for successful project implementation.

During our audits, we found that the most useful information often came from informal discussions, rather than from our carefully constructed audit forms and questionnaires. We also found that Tribal expertise resided in surprising areas (because many Tribal officials and personnel perform multiple roles), and in our implementation plans, we worked to use that expertise for training, project management, and other activities.

Access to Information and Administrative Notes

Unlike most urban communities, small Tribal communities may not have access to digital Internet services, but some may utilize dialup technology. Because of this, additional effort and time should be allocated in transferring information to the Tribal communities. Paper copies may need to be transmitted by mail or fax, depending on the content.

With this limited Internet access, most small communities are at a disadvantage when conducting research on such mainstays of business life as project opportunities and funding information. As an outside resource, a service business may add value by becoming the portal to that Internet-based information for Tribal communities.

During the energy audits, each visit was initiated with an on-site meeting. The meeting was conducted not only to build interest in and commitment to the audit, but also to convey and disseminate information regarding the energy efficiency audits and any new technologies available to the community. Although information was initially transmitted during the pretrip planning, in some instances, the point of contact did not receive the information or did not have the opportunity to review it due to other community concerns of higher priority. In addition, the meeting provided the community leaders the opportunity to discuss concerns and to question auditors on areas that they might be able to support during their visits (Fig. 4).

Therefore, a business expecting to work with Tribal communities should not rely on Internet access and should be understanding of Tribal leaders who may not consider the project to be a priority. Because of the limited time and higher priorities that come with being a Tribal leader, transferred information should be summarized and outlined, followed by contact with the Tribal officials to ensure that any questions, comments, or concerns he or she may have are addressed.

Funding Differences

With a typical energy service project in a city or a town, it is easy to determine who owns the facility, who is responsible for its construction and maintenance, and who would derive benefit from any energy efficiency measures installed. With buildings on Tribal lands, however, the picture is not so clear.

Ownership is a concept that is perceived differently among Tribes, with shared ownership by the entire Tribe, a family, or another group being the norm rather than the exception. In addition, because the laws on Tribal lands are often different from those off the reservations, banks and other financing institutions have historically been uncomfortable with the collateral or the foreclosure procedures required. The result has been that many facilities on reservations and other Tribal lands are inadequate and in need of substantive repair or replacement. From an energy efficiency point of view, that presents an opportunity—if funds can be secured.

Fig. 4 Tradition meets technology: a power-quality meter determines that the wiring in a traditional adobe structure is inadequate and that the transformer is likely undersized.

Often, the first place to look for funds that can be used to implement energy efficiency projects on Tribal lands is the federal government, which under its trust responsibility and as part of its current mandate is encouraging such projects. In addition, several states are focusing on increasing energy efficiency on the Tribal lands within their borders.

There are other instances in which funds are available for either energy efficiency or renewable energy programs from internal Tribal funds produced by casinos or other economic development activities, but government grants and loans form the largest proportion of funds available for such projects. It is important, therefore, for any service provider interested in working with Tribal entities to be familiar with the process of obtaining these grants to move projects forward.

Teamwork and Humility

If one were to develop an equation for the proportion of a successful Tribal project that is related to technical and engineering excellence, and the proportion that is attributable to the development of a project appropriate to the local culture, the importance of technical merit would likely be well under one-third of the project.

Service providers must understand, therefore, that in projects developed on Tribal lands or for rural areas (particularly those in developing countries), as possibly nowhere else, project design and development cannot succeed unless they are true team efforts, in which the service provider/consultant listens to and follows the lead of local Tribal leaders. Technical excellence on its own will go nowhere; only a project that meets the needs (technical, cultural, economic, environmental, and political) of the Tribe and its leaders, and that can be implemented within local constraints, can be accepted and successful.

For this team effort to be possible, service providers must leave the “expert” mantles they are accustomed to wearing in the urban business environment and work hard to be team members, catalysts, and learners—not experts. That requires a fair amount of both flexibility and humility.

One concrete example is that introductions should not focus on one’s career accomplishments, but on one’s family, heritage, and community. Focusing on one’s accomplishments may be interpreted as showing that the presenter believes himself or herself to be better than the audience. In addition, initiating one’s introduction with a welcome in the native Tribal language may be interpreted as a sign of respect but should be carried out only after relationships have been established. A sense of humility is important in becoming a part of the community.

Project Success

It should be evident that although the technology and economic opportunity in a recommended project may be unsurpassed, the success of any project on Tribal lands is very much dependent on a number of factors unrelated to engineering and economics. One must be persistent, humble, understanding, and giving (Fig. 5).

Tribal meetings should be initiated with protocols and processes to which community members are accustomed. This may include saying blessings/prayers, contacting a Tribal elder for sponsorship or introductions, working with Tribal leaders, and presenting introductions in a manner consistent with Tribal values. In addition, one must be prepared to present to the community meetings at a time deemed appropriate by the meeting coordinator, rather than at a time measured on the clock. This requires patience, as one may not be called on for a period of time.

Over time, when trust and relationships have been established, one becomes a part of the community. In this capacity, service providers then should be willing to support the community in areas that may not pertain to the project. In any small community, the lines that urban business culture draws around a project do not exist, and if one is part of a community, one helps as one can. Also, in most small communities that lack access to information, one may become a portal of information for the community by informing Tribal leaders of upcoming opportunities, new technologies, and additional information related to community needs or goals.

As stated previously, small Tribal communities are disadvantaged (in terms of access to services) by their locations. In working with these communities, one must be well prepared logistically and highly organized before starting a project; it is often not possible to just call up a supply house and ask it to make a delivery. For a project to proceed well, persistent (but polite) phone calls, faxes, and emails may be required to ensure that key players are available for support and that information has been transmitted to the appropriate contacts prior to on-site visits.

Fig. 5 Projects and technologies should be appropriate and meet needs, which may call for innovative and creative approaches. There are great renewable energy resources on Tribal lands, but their development sometimes requires different thinking about organizational structure, financing, management, and training.

Because some small Tribal communities are tight-knit circles of families, the success of any project requires community involvement. The key players in the community may dictate the processes and goals of the project, but community Tribal members need to be motivated and informed of the benefits to themselves and to the community. Community members must feel that they are part of the decision-making process, which can be achieved by disseminating information at community meetings and events. If the community members are motivated, Tribal leaders will become interested and make the project a priority.

CONCLUSION

As our audit teams discovered, the success of any project in a small Tribal community is very much dependent on factors other than engineering and economics.

While providing services to small Tribal communities, the authors learned much about the challenges that Tribal leaders and community members face on a daily basis. Location and access to information prove to be challenges when seeking out services required by the community. Services provided by outside organizations are critical to the viability of small Tribal communities, because they provide assistance in introducing new technologies and in fostering economic sustainability. This is particularly true in remote areas, because subject-matter experts may not be available in the area.

As a result, businesses seeking to work with small Tribal communities should be prepared to become part of the community, learning and understanding their values and customs. They should become culturally aware of the community in which they want to work, and they should learn what is important to the members and Tribal leaders (Fig. 6).

Service providers should understand the concerns and challenges of the community and support Tribal leaders by becoming a portal of information leading to interesting opportunities, new technologies, and other pertinent information. They should also empathize with community leaders and members by lending support where needed.

Overall, and most important, one must be persistent, patient, and humble for the project to succeed. As stated earlier, the technology and opportunity may be unsurpassed from the standpoint of engineering and economics, but if humility, understanding, empathy, and cultural awareness do not exist, neither will the project.

Fig. 6 Tradition and a sense of community are values that are becoming more respected in mainstream culture as well. In some Tribal areas where the cultural tradition is remaining in one place rather than practicing a nomadic lifestyle, traditional buildings are very well adapted to the climate and the area, and in fact are being studied by some architects as models for the architecture of the future.

About the Authors

Jackie Francke is a Tribal member of the Navajo Nation Tribe, a mining engineer, and president and principal engineer of Geotechnika, Inc. Francke has more than 15 years of experience working in the field of instrumentation, monitoring, and data collection on projects related to energy efficiency, mining, civil, and environmental engineering. Having grown up on the reservation, Francke understands the challenges Tribes face on a daily basis, and hopes to educate and assist businesses that are looking to work with Tribal communities.

Sandra McCardell is president and founder of Current-C Energy Systems, a small woman-owned firm specializing in efficient and sustainable energy applications in institutional, industrial, and community settings. Her experience over 25 years has ranged from consumer-products companies to international development to real estate to engineering. With a strong background in business and significant experience working in other countries and cultures, she particularly enjoys her projects with Tribal entities.