CONCEPT

Among the most striking of geologic features are mountains, created by several types of tectonic forces, including collisions between continental masses. Mountains have long had an impact on the human psyche, for instance by virtue of their association with the divine in the Greek myths, the Bible, and other religious or cultural traditions. One does not need to be a geologist to know what a mountain is; indeed there is no precise definition of mountain, though in most cases the distinction between a mountain and a hill is fairly obvious. On the other hand, the defining characteristics of a volcano are more apparent. Created by violent tectonic forces, a volcano usually is considered a mountain, and almost certainly is one after it erupts, pouring out molten rock and other substances from deep in the earth.

HOW IT WORKS

Plate Tectonics

Earth is constantly moving, driven by forces beneath its surface. The interior of Earth itself is divided into three major sections: the crust, mantle, and core. The lithosphere is the upper layer of Earth’s interior, including the crust and the brittle portion at the top of the mantle. Tectonism is the deformation of the lithosphere, and the term tectonics refers to the study of this deformation. Most notable among examples of tectonic deformation is mountain building, or orogenesis, discussed later in this essay.

The planet’s crust is not all of one piece: it is composed of numerous plates, which are steadily moving in relation to one another. This movement is responsible for all manner of phenomena, including earthquakes, volcanoes, and mountain building. All these ideas and many more are encompassed in the concept of plate tectonics, which is the name for a branch of geologic and geophysical study and of a dominant principle often described as “the unifying theory of geology” (see Plate Tectonics).

Contents under pressure

Tectonism results from the release and redistribution of energy from Earth’s interior. This energy is either gravitational, and thus a function of the enormous mass at the planet’s core, or thermal, resulting from the heat generated by radioactive decay. Differences in mass and heat within the planet’s interior, known as pressure gradients, result in the deformation of rocks, placing many forms of stress and strain on them.

In scientific terms, stress is any attempt to deform an object, and strain is a change in dimension resulting from stress. Rocks experience stress in the form of tension, compression, and shear. Tension acts to stretch a material, whereas compression is a form of stress produced by the action of equal and opposite forces, whose effect is to reduce the length of a material. (Compression is a form of pressure.) Shear results from equal and opposite forces that do not act along the same plane. If a thick, hardbound topic is lying flat, and one pushes the front cover from the side so that the covers and pages are no longer in alignment, is an example of shear.

Rocks manifest the strain resulting from these stresses by warping, sliding, or breaking. They may even flow, as though they were liquids, or melt and thus truly become liquid. As a result, Earth’s interior may manifest faults, or fractures in rocks, as well as folds, or bends in the rock structure. The effects can be seen on the surface in the form of subsidence, which is a depression in the crust; or uplift, the raising of crustal materials. Earthquakes and volcanic eruptions also may result.

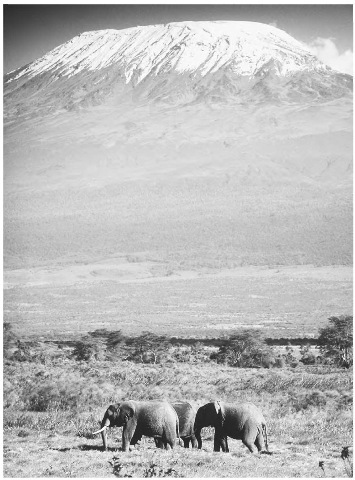

Mountains sometimes arise in isolation, as was the case with Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania.

Orogenesis

There are two basic types of tectonism: epeirogenesis and orogenesis. The first takes its name from the Greek words epeiros, meaning “main-land,” and genesis, or “origin.” Epeirogenesis, which takes the form of either uplift or subsidence, is a chiefly vertical form of movement and plays little role in either plate tectonics or mountain building.

Orogenesis, on the other hand, is mountain building, as the prefix oros (“mountain”) shows. Orogenesis involves the formation of mountain ranges by means of folding, faulting, and volcanic activity—lateral movements as opposed to vertical ones. Geologists typically use the term orogenesis, instead of just “mountain building,” when discussing the formation of large belts of mountains from tectonic processes.

Plate margins

Plates may converge (move toward one another), diverge (move away from one another), or experience transform motion, meaning that they slide against one another. Convergence usually is associated with subduction, in which one plate is forced down into the mantle and eventually undergoes partial melting. This typically occurs in the ocean, creating a depression known as an oceanic trench.

There are three types of plate margins, or boundaries between plates, depending on the two types of crusts that interact: oceanic with oceanic, continental with continental, or continental with oceanic. Any of these margins may be involved in mountain formation. Orogenic belts, or mountain belts, typically are situated in sub-duction zones at convergent plate boundaries and consist of two types.

The first type occurs when igneous material (i.e., rock from volcanoes) forms on the upper plate of a subduction zone, causing the surface to rise. This can take place either in the oceanic crust, in which case the mountains formed are called island arcs, or along continental-oceanic margins. The Aleutian Islands are an example of an island arc, while the Andes range represent mountains formed by the subduction of an oceanic plate under a continental one.

The second type of mountain belt occurs when continental plates converge or collide. When continental plates converge, one plate may “try” to subduct the other, but ultimately the buoyancy of the lower plate (which floats, as it were, on the lithosphere) pushes it upward. The result is the creation of a wide, unusually thick or “tall” belt. An example is the Himalayas, the world’s tallest mountain range, which is still being pushed upward as the result of a collision between India and Asia that happened some 30 million years ago. (See Plate Tectonics for more about continental drift and collisions between plates.)

REAL-LIFE APPLICATIONS

What Is a Mountain?

In the 1995 film The Englishman Who Went Up a Hill But Came Down a Mountain, the British actor Hugh Grant plays an English cartographer, or mapmaker, sent in 1917 by his government to measure what is purportedly “the first mountain inside Wales.” He quickly determines that according to standards approved by His Majesty, the “mountain” in question is, in fact, a hill. Much of the film’s plot thereafter revolves around attempts on the part of the villagers to rescue their beloved mountain from denigration as a “hill,” a fate they prevent by piling enough rocks and dirt onto the top to make it meet specifications.

This comedy aptly illustrates the somewhat arbitrary standards by which people define mountains. The British naturalist Roderick Peat-tie (1891-1955), in his 1936 topic Mountain Geography, maintained that mountains are distinguished by their impressive appearance, their individuality, and their impact on the human imagination. This sort of qualitative definition, while it is certainly intriguing, is of little value to science; fortunately, however, more quantitative standards exist.

In Britain and the United States, a mountain typically is defined as a landform with an elevation of 985 ft. (300 m) above sea level. This was the standard applied in The Englishman, but the Welsh villagers would have had a hard time raising their “hill” to meet the standards used in continental Europe: 2,950 ft. (900 m) above sea level. This seems to be a more useful standard, because the British and American one would take in high plains and other nonmountainous regions of relatively great altitude. On the other hand, there are landforms in Scotland that rise only a few hundred meters above sea level, but their morphologic characteristics or shape seem to qualify them as mountains. Not only are their slopes steep, but the presence of glaciers and snowcapped peaks, with their attendant severe weather and rocky, inhospitable soil, also seem to indicate the topography associated with mountains.

Mountain Geomorphology

One area of the geologic sciences especially concerned with the study of mountains is geomorphology, devoted to the investigation of land-forms. Geomorphologists studying mountains must draw on a wide variety of disciplines, including geology, climatology, biology, hydrology, and even anthropology, because, as discussed at the conclusion of this essay, mountains have played a significant role in the shaping of human social groups.

From the standpoint of geology and plate tectonics, mountain geomorphology embraces a complex of characteristic formations, not all of which are necessarily present in a given orogen, or mountain. These include forelands and fore-deeps along the plains; foreland fold-and-thrust belts, which more or less correspond to “foothills” in layperson’s terminology; and a crystalline core zone, composed of several types of rock, that is the mountain itself.

Environmental zones

Mountain geomorphology classifies various environmental zones, from lowest to highest altitude. Near the bottom are flood plains, river terraces, and alluvial fans, all areas heavily affected by rivers flowing from higher elevations. (In fact, many of the world’s greatest rivers flow from mountains, examples being the Himalayan Ganges and Indus rivers in Asia and the Andean Amazon in South America.) Farming villages may be found as high as the 9,845-ft. to 13,125ft. range (3,000-4,000 m), an area known as a submontane, or forested region.

The tree line typically lies at an altitude of 14,765 ft. (4,500 m). Above this point, there is little human activity but plenty of geologic activity, including rock slides, glacial flow, and, at very high altitudes, avalanches. From the tree line upward, the altitude levels that mark a particular region are differentiated for the Arctic and tropical zones, with much lower altitudes in the Arctic mountains. For instance, the tree line lies at about 330 ft. (100 m) in the much colder Arctic zone.

Above the tree line is the subalpine, or montane, region. The mean slope angle of the mountain is less steep here than it is at lower or higher elevations: in the submontane, or forested region, below the tree line, the slope is about 30°, and above the subalpine, in the high alpine, the slope can become as sharp at 65°. In the sub-alpine, however, it is only about 20°, and because grass (if not trees) grows in this region, it is suited for grazing.

It may seem surprising to hear of shepherds bringing sheep to graze at altitudes of 16,400 ft. (5,000 m), as occurs in tropical zones. This does not necessarily mean that people live at such altitudes; more often than not, mountain dwellers have their settlements at lower elevations, and shepherds simply take their flocks up into the heights for grazing. Yet the ancient Bolivian city of Tiahuanaco, which flourished in about a.d. 600—some four centuries before the rise of the Inca—lay at an almost inconceivable altitude of 13,125 ft. (4,000 m), or about 2.5 times the elevation of Denver, Colorado, America’s Mile-High City.

Classifying Mountains

There are several ways to classify mountains and groups of mountains. Mountain belts, as described earlier, typically are grouped according to formation process and types of plates: island arcs, continental arcs (formed with the subduction of an oceanic plate by a continental plate), and collisional mountain belts. Sometimes a mountain arises in isolation, an example being Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, Africa. Another example is Stone Mountain outside Atlanta, an exposed pluton, or a mass of crystalline igneous rock that forms deep in Earth’s crust and rises. Many volcanoes, which we discuss later, arise individually, but mountains are most likely to appear in conjunction with other mountains. One such grouping, though far from the only one, is a mountain range, which can be defined as a relatively localized series of peaks and ridges.

Ranges, chains, and masses

Some of the world’s most famous mountain ranges include the Himalayas, Karakoram Range, and Pamirs in central Asia; the Alps and Urals in Europe; the Atlas Mountains in Africa; the Andes in South America; and the Cascade Range, Sierra Nevada, Rocky Mountains, and Appalachians as well as their associated ranges in North America. Ranges affiliated with the Appalachians, for instance, include the Great Smokies in the south and the Adirondacks, Alleghenies, and Poconos in the north.

Several of the examples given here illustrate the fact that ranges are not the largest groupings of mountains. Sometimes series of ranges stretch across a continent for great distances in what are called mountain chains, an example of which is the Mediterranean chain of Balkans, Apennines, and Pyrenees that stretches across southern Europe.

There also may be irregular groupings of mountains, which lack the broad linear sweep of mountain ranges or chains and which are known as mountain masses. The mountains surrounding the Tibetan plateau represent an example of a mountain mass. Finally, ranges, chains, and masses of mountains may be combined to form vast mountain systems. An impressive example is the Alpine-Himalayan system, which unites parts of the Eurasian, Arabian, African, and Indo-Aus-tralian continental plates.

Other types of mountain

There are certain special types of orogeny, as when ocean crust subducts continental crust— something that is not supposed to happen but occasionally does. This rare variety ofsubduction is called obduction, and the mountains produced are called ophiolites. Examples include the uplands near Troodos in Cyprus and the Taconic Mountains in upstate New York.

Fault-block mountains appear when two continental masses push against each other and the upper portion of a continental plate splits from the deeper rocks. A portion of the upper crust, usually several miles thick, begins to move slowly across the continent. Ultimately it runs into another mass, creating a ramp. This can result in unusually singular mountains, such as Chief Mountain in Montana, which slid across open prairie on a thrust sheet.

Under the ocean is the longest mountain chain on Earth, the mid-ocean ridge system, which runs down the center of the Atlantic Ocean and continues through the Indian and Pacific oceans. Lava continuously erupts along this ridge, releasing geothermal energy and opening up new strips of ocean floor. This brings us to a special kind of mountain, typically resulting from the sort of dramatic plate tectonic processes that also produce earthquakes: volcanoes.

Volcanoes

Most volcanoes are mountains, and for this reason, it is appropriate to discuss them together; however, a volcano is not necessarily a mountain. A volcano may be defined as a natural opening in Earth’s surface through which molten (liquid), solid, and gaseous material erupts. The word volcano also is used to describe the cone of erupted material that builds up around the opening or fissure. Because these cones are often quite impressive in height, they frequently are associated with mountains.

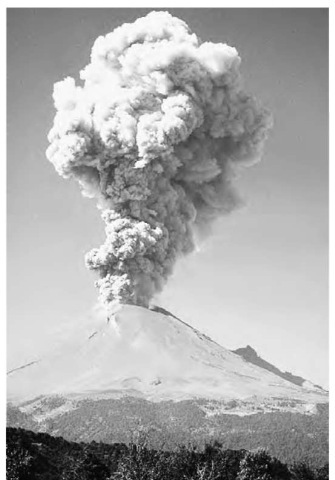

The Popocatepetl volcano erupts, spewing ash, rocks, and gases.

Though volcanic activity has been the case of death and destruction, it is essential to the planet’s survival. Volcanic activity is the principal process through which chemical elements, minerals, and other compounds from Earth’s interior reach its surface. These substances, such as carbon dioxide, have played a major role in the development of the planet’s atmosphere, waters, and soils. Even today, soil in volcanic areas is among the richest on Earth. Volcanoes provide additional benefits in their release of geothermal energy, used for heating and other purposes in such countries as Iceland, Italy, Hungary, and New Zealand (see Energy and Earth). In addition, volcanic activity beneath the oceans promises to supply almost limitless geothermal energy,once the technology for its extraction becomes available.

Formation of volcanoes

As noted earlier, land volcanoes are formed in coastal areas where continental and oceanic plates converge. As the oceanic plate is subducted and pushed farther and farther beneath the continental surface, the buildup of heat and pressure results in the melting of rock. This molten rock, or magma, tends to rise toward the surface and collect in magma reservoirs. Pressure buildup in the magma reservoir ultimately pushes the magma upward through cracks in Earth’s crust, creating a volcano.

Volcanoes also form underwater, in which case they are called seamounts. Convergence of oceanic plates causes one plate to sink beneath the other, creating an oceanic trench; as a result, magma rises from the subducted plate to fashion volcanoes. If the plates diverge, magma seeps upward at the ridge or margin between plates, producing more seafloor. This process, known as seafloor spreading, leads to the creation of volcanoes on either side of the ridge.

In some places a plate slides over a stationary area of volcanic activity, known as a hot spot. These are extremely hot plumes of magma that well up from the crust, though not on the edge or margin of a plate. A tectonic plate simply drifts across the hot spot, and as it does, the area just above the hot spot experiences volcanic activity. Hot spots exist in Hawaii, Iceland, Samoa, Bermuda, and America’s Yellowstone National Park.

Classifying volcanoes

Volcanoes can be classified in terms of their volcanic activity, in which case they are labeled as active (currently erupting), dormant (not currently erupting but likely to do so in the future), or extinct. In the case of an extinct volcano, no eruption has been noted in recorded history, and it is likely that the volcano has ceased to erupt permanently.

In terms of shape, volcanoes fall into four categories: cinder cones, composite cones, shield volcanoes, and lava domes. These types are distinguished not only by morphologic characteristics but also by typical sizes and even angles of slope. For instance, cinder cones, built of lava fragments, have slopes of 30° to 40°, and are seldom more than 1,640 ft. (500 m) in height.

Composite cones, or stratovolcanoes, are made up of alternating layers of lava (cooled magma), ash, and rock. (The prefix strato refers to these layers.) They may slope as little as 5° at the base and as much as 30° at the summit. Stra-tovolcanoes may grow to be as tall as 2-3 mi. (3.2-4.8 km) before collapsing and are characterized by a sharp, dramatic shape. Examples include Fuji, a revered mountain that often serves as a symbol of Japan, and Washington state’s Mount Saint Helens.

A shield volcano, which may be a solitary formation and often is located over a hot spot, is built from lava flows that pile one on top of another. With a slope as little as 2° at the base and no more than 10° at the summit, shield volcanoes are much wider than stratovolcanoes, but sometimes they can be impressively tall. Such is the case with Mauna Loa in Hawaii, which at 13,680 ft. (4,170 m) above sea level is the world’s largest active volcano. Likewise, Mount Kilimanjaro, though long ago gone dormant, is the tallest mountain in Africa.

Finally, there are lava domes, which are made of solid lava that has been pushed upward. Closely related is a volcanic neck, which often forms from a cinder cone. In the case of a volcanic neck, lava rises and erupts, leaving a mountain that looks like a giant gravel heap. Once it has become extinct, the lava inside the volcano begins to solidify. Over time the rock on the exterior wears away, leaving only a vent filled with solidified lava, usually in a funnel shape. A dramatic example of this appears at Shiprock, New Mexico.

Volcanic eruptions

Volcanoes frequently are classified by the different ways in which they erupt. These types of eruption, in turn, result from differences in the material being disgorged from the volcano. When the magma is low in gas and silica (silicon dioxide, found in sand and rocks), the volcano erupts in a relatively gentle way. Its lava is thin and spreads quickly. Gas and silica-rich magma, on the other hand, brings about a violent explosion that yields tarlike magma.

There are four basic forms or phases of volcanic eruption: Hawaiian, Strombolian, Vulcan-ian, and Peleean. The Hawaiian phase is simply a fountain-like gush of runny lava, without any explosions. The Strombolian phase (named after a volcano on a small island off the Italian peninsula) involves thick lava and mild explosions. In a Vulcanian phase, magma has blocked the volcanic vent, and only after an explosion is the magma released, with the result that tons of solid material and gases are hurled into the sky. Most violent of all is the Peleean, named after Mount Pelee on Martinique in the Caribbean (discussed later). In the Peleean phase, the volcano disgorges thick lava, clouds of gas, and fine ash, all at formidable velocities.

Crater Lake in Oregon is the result of the collapse of a magma chamber after a volcanic eruption. This collapse forms a bowl-like crater called a caldera, which fills with water.

Accompanying a volcanic eruption in many cases are fierce rains, the result of the expulsion of steam from the volcano, after which the steam condenses in the atmosphere to form clouds. Gases thrown into the atmosphere are often volatile and may include hydrogen sulfide, fluorine, carbon dioxide, and radon. All are detrimental to human beings when present in sufficient quantity, and radon is radioactive.

Not surprisingly, the eruption of a volcano completely changes the morphologic characteristics of the landform. During the eruption a crater is formed, and out of this flows magma and ash, which cool to form the cone. In some cases, the magma chamber collapses just after the eruption, forming a caldera, or a large, bowl-shaped crater. These caldera (the plural as well as singular form) may fill with water, as was the case at Oregon’s Crater Lake.

Infamous volcanic disasters

Volcanoes result from some of the same tectonic forces as earthquakes (see Seismology), and, not surprisingly, they often have resulted in enormous death and destruction. Some remarkable examples include:

• Vesuvius, Italy, a.d. 79 and 1631: Situated along the Bay of Naples in southern Italy, Vesuvius has erupted more than 50 times during the past two millennia. Its most famous eruption occurred in a.d. 79, when the Roman Empire was near the height of its power. The first-century eruption buried the nearby towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, where bodies and buildings were preserved virtually intact until excavation of the area in 1748. Another eruption, in 1631, killed some 4,000 people.

• Krakatau, Indonesia, a.d. 535 (?) and 1883: The most famous eruption of Krakatau occurred in 1883, resulting in the loss of some 36,000 lives. The explosion, which was heard 3,000 mi. away, threw 70-lb. (32-kg) boulders as far as 50 mi. (80 km). It also produced a tsunami, or tidal wave, 130 ft.

(40 m) high, which swept away whole villages. In addition, the blast hurled so much dust into the atmosphere that the Moon appeared blue or green for two years. It is also possible that Krakatau erupted in about a.d. 535, causing such a change in the atmosphere that wide areas of the world experienced years without summer. (See Earth Systems for more on this subject.)

• Tambora, Indonesia, 1815: Another Indonesian volcano, Tambora, killed 12,000 people when it erupted in 1815. As with Krakatau in 535, this eruption was responsible for a year without summer in 1816 (see Earth Systems).

• Pelee, Martinique, 1902: When Mount Pelee erupted on the Caribbean island of Martinique, it sent tons of poisonous gas and hot ash spilling over the town of Saint-Pierre, killing all but four of its 29,937 residents.

• Saint Helens, Washington, 1980: Relatively small compared with earlier volcanoes, the Mount Saint Helens blast is still significant because it was so recent and took place in the United States. The eruption sent debris flying upward 1,300 ft. (396 m) and caused darkness over towns as far as 85 mi. (137 km) away. Fifty-seven people died in the eruption and its aftermath.

• Pinatubo, Philippines, 1991: Dormant for 600 years, Mount Pinatubo began to rumble one day in 1991 and, after a few days, erupted in a cloud that spread ash 6 ft. (1.83 m) deep along a radius of 2 mi. (3.2 km). A U.S. air base 15 mi. (24 km) away was buried. The blast threw 20 million tons (18,144,000 metric tons) of sulfuric acid 12 mi. (19 km) into the stratosphere, and the cloud ultimately covered the entire planet, resulting in moderate cooling for a few weeks.

The Impact of Mountains

Volcanic eruptions are among the most dramatic effects produced by mountains, but they are far from the only ones. Every bit as fascinating are the effects mountains produce on the weather, on the evolution of species, and on human society. In each case, mountains serve as a barrier or separator—between masses of air, clouds, and populations.

Wind pushes air and moisture-filled clouds up mountain slopes, and as the altitude increases, the pressure decreases. As a result, masses of warm, moist air become larger, cooler, and less dense. This phenomenon is known as adiabatic expansion, and it is the same thing that happens when an aerosol can is shaken, reducing the pressure of gases inside and cooling the surface of the can. Under the relatively high-pressure and high-temperature conditions of the flatlands, water exists as a gas, but in the heights of the mountaintops, it cools and condenses, forming clouds.

Rain shadows

As the clouds rise along the side of the mountain, they begin to release heavy droplets in the form of rain and, at higher altitudes, snow. By the time the cloud crosses the top of the mountain, however, it will have released most of its moisture, and hence the other side of the mountain may be arid. The leeward side, or the side opposite the wind, becomes what is called a rain shadow.

Although they are only 282 mi. (454 km) apart, the cities of Seattle and Spokane, Washington, have radically different weather patterns. Famous for its almost constant rain, Seattle lies on the windward, or wind-facing, side of the Cascade Range, toward the Pacific Ocean. On the leeward side of the Cascades is Spokane, where the weather is typically warm and dry. Though it is only on the other side of the state, Spokane might as well be on the other side of the continent. Indeed, it is associated more closely with the arid expanses of Idaho, whereas Seattle belongs to a stretch of cold, wet Pacific terrain that includes San Francisco and Portland, Oregon.

Much of the western United States consists of deserts formed by rain shadows or, in some cases, double rain shadows. Much of New Mexico, for instance, lies in a double rain shadow created by the Rockies in the west and Mexico’s Sierra Madres to the south. In southern California, tall redwoods line the lush windward side of the Sierra Nevadas, while Death Valley and the rest of the Mojave Desert lies in the rain shadow on the eastern side. The Great Basin that covers eastern Oregon, southern Idaho, much of Utah, and almost all of Nevada, likewise is created by the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada-Cascade chain.

Mountains and species

One of the most intriguing subjects involved in the study of mountains is their effects on large groups of plants, animals, and humans. Mountains may separate entire species, creating pockets of flora and fauna virtually unknown to the rest of the world. Thus, during the 1990s, huge numbers of species that had never been catalogued were discovered in the mountains of southeast Asia.

KEY TERMS

Active: A term to describe a volcano that is currently erupting.

Compression: A form of stress produced by the action of equal and opposite forces, the effect of which is to reduce the length of a material. Compression is a form of pressure.

Convergence: A tectonic process whereby plates move toward each other.

Crust: The uppermost division of the solid earth, representing less than 1% of its volume and varying in depth from 3 mi. to 37 mi. (5-60 km). Below the crust is the mantle.

Divergence: A tectonic process whereby plates move away from each other.

Dormant: A term to describe a volcano that is not currently erupting but is likely to do so in the future.

Epeirogenesis: One of two principal forms of tectonism, the other being orogenesis. Derived from the Greek words epeiros (“mainland”) and genesis (“origins”), epeirogenesis takes the form of either uplift or subsidence.

Extinct: A term to describe a volcano for which no eruption has been known in recorded history. In this case, it is likely that the volcano has ceased to erupt permanently.

Geomorphology: An area of physical geology concerned with the study of landforms, with the forces and processes that have shaped them, and with the description and classification of various physical features on Earth.

Hot spot: A region of high volcanic activity.

Landform: A notable topographical feature, such as a mountain, plateau, or valley.

Lithosphere: The upper layer of Earth’s interior, including the crust and the brittle portion at the top of the mantle.

Mantle: The thick, dense layer of rock, approximately 1,429 mi. (2,300 km) thick, between Earth’s crust and its core.

Morphology: Structure or form or the study thereof.

Mountain chain: A series of ranges stretching across a continent for a great distance.

Mountain mass: An irregular grouping of mountains, which lacks the broad linear sweep of a range or chain.

Mountain range: A relatively localized series of peaks and ridges.

Mountain system: A combination of ranges, chains, and masses of mountains that stretches across vast distances, usually encompassing more than one continent.

Oros: A Greek word meaning “mountain,” which appears in such words as orogeny, a variant of orogenesis; orogen, another term for “mountain” and orogenic, as in “orogenic belt.”

Orogenesis: One of two principal forms of tectonism, the other being epeirogenesis. Derived from the Greek words oros (“mountain”) and genesis (“origin”), orogenesis involves the formation of mountain ranges by means of folding, faulting, and volcanic activity. The processes of orogenesis play a major role in plate tectonics.

Plate margins: Boundaries between plates.

Plate tectonics: The name both of a theory and of a specialization of tectonics. As an area of study, plate tectonics deals with the large features of the litho-sphere and the forces that shape them. As a theory, it explains the processes that have shaped Earth in terms of plates and their movement.

Plates: Large, movable segments of the lithosphere.

Shear: A form of stress resulting from equal and opposite forces that do not act along the same line. If a thick, hardbound topic is lying flat, and one pushes the front cover from the side so that the covers and pages are no longer aligned, this is an example of shear.

Strain: The ratio between the change in dimension experienced by an object that has been subjected to stress and the original dimensions of the object.

Stress: In general terms, any attempt to deform a solid. Types of stress include tension, compression, and shear.

Subsidence: A term that refers either to the process of subsiding, on the part of air or solid earth, or, in the case of solid earth, to the resulting formation. Subsidence thus is defined variously as the downward movement of air, the sinking of ground, or a depression in Earth’s crust.

Tectonics: The study of tectonism, including its causes and effects, most notably mountain building.

Tectonism: The deformation of the lithosphere.

Tension: A form of stress produced by a force that acts to stretch a material.

Topography: The configuration of Earth’s surface, including its relief as well as the position of physical features.

Uplift: A process whereby the surface of Earth rises, as the result of either a decrease in downward force or an increase in upward force.

Volcano: A natural opening in Earth’s surface through which molten (liquid), solid, and gaseous material erupts. The word volcano is also used to describe the cone of erupted material that builds up around the opening or fissure.

The formation of mountains and other landforms may even lead to speciation, a phenomenon in which members of a species become incapable of reproducing with other members, thus creating a new species. When the Colorado River cut open the Grand Canyon, it separated groups of squirrels that lived in the high-altitude pine forest. Over time these populations ceased to interbreed, and today the Kaibab squirrel of the north rim and the Abert squirrel of the south are separate species, no more capable of interbreeding than humans and apes.

Human societies and mountains

Although the Appalachians of the eastern United States are hundreds of millions of years old, most ranges are much younger. Most will erode or otherwise cease to exist in a relatively short time (short, that is, by geologic standards), yet to humans throughout the ages,mountains have seemed a symbol of permanence. This is just one aspect of mountains’ impact on the human psyche.

In his 1975 study of symbolism in political movements, Utopia and Revolution, Melvin J. Lasky devoted considerable space to the mountain and its association with divinity through figures such as the Greek Olympians and Noah and Moses in the Bible. Clearly, mountains have proved enormously influential on human attitudes, and nowhere is this more obvious than in relation to the people who live in the mountains. Whether the person is a coal miner from Appalachia or a rancher from the Rockies, a Scottish highlander or a Quechua-speaking Peruvian, the mentality is similar, characterized by a combination of hardiness, fierce independence, and disdain for lowland ways.

These characteristics, combined with the harsh weather of the mountains, have made mountain warfare a challenge to lowland invaders. This explains the fact that Switzerland has kept itself free from involvement in European wars since Napoleon’s time, and why the independent Scottish Highlands were long a thorn in England’s side. It also explains why neither the British nor the Russian empires could manage to control Afghanistan fully during their struggle over that mountainous nation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Britain eventually pulled out of the “Great Game,” as this struggle was called, but Russia never really did. Many years later, the Soviets became bogged down in a war in Afghanistan that they could not win. The war, which lasted from 1979 to 1989, helped bring about the end of the Soviet Union and its system of satellite dictatorships. More than a decade later, as the United States launched strikes against Afghanistan in 2001, a superpower once again faced the challenge posed by one of the poorest, most inhospitable nations on Earth.

But the independence of the mountaineer is deceptive; in fact, mountains have little to offer, economically, other than their beauty and the resources deep beneath their surfaces. In other words, they are really of value only to flatland tourists and mining companies. Since few mountain environments offer much promise agriculturally, the people of the mountains are dependent on the flatlands for sustenance. Gorgeous and rugged as they are, such mountainous states as Colorado or Wyoming might be as poor as Afghanistan were it not for the fact that they belong to a larger political unit, the United States.