introduction

The purpose of the Sloan Consortium (Sloan-C) is to help learning organizations continually improve quality, scale, and breadth according to their own distinctive missions, so that education will become a part of everyday life, accessible and affordable for anyone, anywhere, at any time, in a wide variety of disciplines. Created with funding from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Sloan-C encourages the collaborative sharing of knowledge and effective practices to improve online education in learning effectiveness, access, affordability for learners and providers, and student and faculty satisfaction.

Sloan-C maintains a catalog of degree and certificate programs offered by a wide range of regionally accredited member institutions, consortia, and industry partners; provides speakers and consultants to help institutions learn about online methodologies; hosts conferences and workshops to help implement and improve online programs; publishes the newsletter The Sloan-C View: Perspectives in Quality Online Education, the peer-reviewed Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks (JALN), and annual volumes of applied research studies; and conducts research, surveys, and forums to inform academic, government, and private-sector audiences. Sloan-C also offers services such as awards, conferences and workshops, an effective practices database, and peer-reviewed listings in the Sloan-C catalog for regionally accredited members with online degree and certificate programs.

Sloan-C generates ideas to improve products, services, and standards for the online learning industry, and assists members in collaborative initiatives. Members include: a) private and public universities and colleges, community colleges, other accredited course and degree providers, and professional associations that support education; and b) organizations and suppliers of services, equipment, and tools that demonstrate the Sloan-C quality principles. Associate memberships are available to institutions that share an interest in online education and Sloan-C goals, but that have not yet listed online programs. As of mid-2004, membership was fully underwritten by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

history

In 1993, the Sloan Consortium began as an idea in a meeting convened by Frank Mayadas, the Project Director for the Alfred P. Sloan program for anytime-anyplace learning. Leading practitioners from schools that were developing online education courses and programs met at the Omni Hotel in Manhattan (The Sloan Consortium, 2003a) to consider the potential that electronic communications could bring to learning outside the classroom. In The Network Nation, Human Communications via Computer, Hiltz and Turoff (1981) had already used the term “learning networks”; “asynchronous” was added to create the now familiar name “asynchronous learning networks” or ALNs. “Asynchronous” conveys the idea that people learn at various times, and not necessarily all at the same time and in the same place: “ALNs are people-networks for anytime-anywhere learning.ALN combines self-study with substantial, rapid asynchronous interactivity with others” (Bourne, Mayadas & Campbell, 2000, p. 63).

Founded in 1934 as a non-profit philanthropic organization, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation improves quality of life by supporting initiatives in science and education. Its program for anytime-anyplace learning seeks to make available high quality-learning, education, and training, anytime and anywhere, for those motivated to seek it. Through ALNs, learners can access instructors, classmates, course assignments, and other educational resources over the Internet. During the past decade, the Sloan Foundation has committed approximately $48 million to ALNs, including grants to colleges and universities, and planning and dissemination activities, with the goal of making higher education “an ordinary part of everyday life” (Gomory, 2000).

activities

In its first years, the ALN administrative center was at Vanderbilt University under the direction of John R. Bourne; in 2000 the center moved with him to the Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering and Babson College in Needham, Massachusetts. Now called the Sloan Center for OnLine Education (SCOLE), the center is the administrative home for Sloan-C activities. Not yet formally incorporated, Sloan-C activities are funded by the Sloan Foundation, guided by its board members, and enabled by its administrative staff and membership.

As the Executive Director of Sloan-C at SCOLE, Bourne is the founder and editor-in-chief of the Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks (JALN), a widely read, peer-reviewed, online journal that is acknowledged as a major resource for knowledge about online learning. Inaugurated in March 1997 as the premier online journal in its field, JALN features peer-reviewed papers based on results that are supported with empirical data. In 2000, SCOLE also began publishing an annual series of volumes on quality in online education, collections of case studies that emerged from annual invitational research workshops. Each of the volumes is disseminated for knowledge sharing among wider audiences of practitioners in book form and via annual online workshop series. A major activity each year is the annual conference, which attracts more than 500 practitioners. Hosted by the University of Central Florida, and chaired by Miller of Penn State, the 10th Sloan-C International Conference on Asynchronous Learning Networks: From Innovation to Mainstream convened in November 2004 in Orlando, Florida. Sloan-C Conference proceedings and presentations are archived and accessible online.

The Sloan Consortium Catalog lists more than 600 online peer-reviewed degree and certificate programs. The Sloan-C homepage (http://www.sloan-c.org) cites membership including more than 500 colleges, universities, state systems, consortia, and organizational members who work:

…to help learning organizations continually improve quality, scale, and breadth according to their own distinctive missions, so that education will become a part of everyday life, accessible and affordable for anyone, anywhere, at any time, in a wide variety of disciplines.

As a network of people helping to advance online learning, Sloan-C members freely access Sloan-C at http://www.sloan-c.org for resources including JALN, the Sloan-C View newsletter, annual volumes in the Sloan-C quality series on online education, the database of effective practices, the bureau of speakers and consultants, listservs, annual and occasional conferences and workshops (online and face-to-face), awards, the annual national survey of the status of online learning, and the Sloan-C catalog of online programs.

From its inception, Sloan-C emphasized that the “networks” in ALN include not just technological infrastructures, but the people networks that ALN supports in ways not possible before. “We think of every person on the network as both a user and a resource,” says Mayadas (1997). Thus, online communications are a powerful, technology-assisted means for rapid communications among multiple audiences (Mayadas, 2003).

In the history of higher education, the potential of ALN for making higher education much more widely accessible and for constructing knowledge communities is unparalleled. ALN also promises to bridge divides between the two parallel, but frequently separate worlds of academic and corporate learning. Because ALN is a truly new and disruptive technology, Sloan-C finds it is useful to identify principles and metrics that can help establish benchmarks and standards for quality. Thus, Sloan-C members endorse a multi-perspectival framework that is based on continuous quality improvement.

Five principles, known as the pillars of quality (see Table 1), guide the familiar process of identifying goals and benchmarks, measuring progress towards goals, refining methods, and continuously improving outcomes. The pillars are learning effectiveness, cost effectiveness, access, faculty satisfaction, and student satisfaction. The process and the principles align in academic educational environments as well as they do in corporate training environments (The Sloan Consortium, 2003b).

Sloan-C’s early demonstration of the value of ALN, and its knowledge- and community-building activities, has contributed to today’s environment in which over 95% of all for-credit, degree-oriented instruction in the country—enrolling 2.5 to 3 million learners in the 2001/2002 academic year (Allen & Seaman, 2003)— follows the Sloan-C ALN model. Sloan-C’s role is widely recognized in the higher education community and in government, as consensus develops about the elements of good pedagogy, high quality, and costs.

In terms of quality standards, Sloan-C sets the expectation that at each institution, learning online should be at least as effective as learning in other modes according to the institutional norm. For Sloan-C, ALN is generally characterized by cohort-style classes, with definite start and end dates, in faculty-led courses with student/faculty ratios approximately the same as for traditional classes, with provision for and encouragement of interaction among students as well as with the instructor, and with relatively low-cost course and media development. The ALN emphasis on interaction among people contrasts with many other approaches that emphasize expensive course materials as the main source of instruction and that place much less emphasis on interaction among the people in the course.

Clearly, good and bad results can be achieved in either online or traditional classroom teaching depending on the quality, skill, and motivation of the instructor and students. The majority of Sloan-C research demonstrates increasingly high levels of faculty and student satisfaction, and despite findings that indicate online teaching and learning take more time, nearly all faculty who have taught online wish to repeat the experience. Growing enrollments indicate that students also wish to repeat the experience. Creation of online courses need not be expensive, and courses once created can be easily revised, and over time, cost a little less to deliver than in a traditional classroom. Most significantly, online learning increases access to quality education for many, many people who would otherwise be denied this opportunity.

Programs that are approved for listing in the Sloan-C catalog are peer reviewed and provide evidence of compliance with the criteria above. As the goal of anytime, anyplace, affordable access moves closer to reality, the table of programs (see Table 2) indicates significant progress in the quality, scale, and breadth of many areas of study.

quality framework

In the business of education—‘to improve learning while achieving capacity enrollment’—continuous quality improvement (CQI) helps people to set goals, identify resources and strategies, and measure progress towards the institution’s ideal vision of its distinctive purpose” (italicized quotation from Miller, cited in Moore, 2002). Thus, as in the brief version of the quality framework in Table 3, the goals of each of the five pillars are presented in CQI terms for measuring continuously improving learning, affordability, access, and faculty and student satisfaction—interactive components that focus on improving people networks, practices, achievement, and growth.

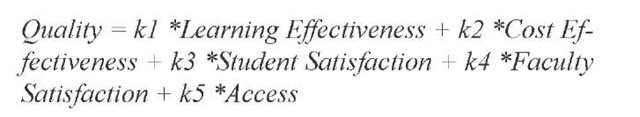

Sloan-C keeps in mind that quality is a work in progress and seeks to measure quality in terms of each organization’s own distinctive, dynamic mission and the people who embody it. Thus, the Sloan-C quality framework enables each organization to set its own standard for each pillar. For example, a school could weight the importance of each measure in the following equation:

For a selective admissions school, k5 *Access would be not as important as it is for open admissions schools. Further, an organization can take different looks at the scales (e.g., Learning Effectiveness on a scale of how it compares to others as in the National Study of Student Engagement, or Cost Effectiveness according to U.S. news reports, or even Student Satisfaction according to MSN’s Best Party Schools).

In more general terms, for each of the pillars, the statements below describe an ideal environment:

Table 1. Higher education and corporate ALN

|

Quality Principles |

For Higher Education |

For Corporations |

|

(Moore 2002) |

(Oblinger, 2003) |

|

|

Learning Effectiveness |

Learning effectiveness, new knowledge, applied theory, continuous feedback from stakeholders |

Productivity, improved operations |

|

Cost Effectiveness |

Cost effectiveness, brand recognition, scalability, public service and influence, prestige, funding |

Cost savings, brand, market capture |

|

Access |

Wider access including international communities, greater research and development opportunities, faster response to new fields of study, capacity enrollment |

Market growth, distributed team work |

|

Faculty (Employee) Satisfaction |

New populations of students and colleagues, greater satisfaction with teaching and learning |

Competition, competitive intelligence, understanding |

|

Student (Customer) Satisfaction |

Learner and teacher satisfaction and loyalty; career opportunities including OJT, internships, and mentorships |

Recruitment and retention |

Learning Effectiveness

• The provider demonstrates that the quality of learning online is comparable to the quality of its traditional programs:

• Interaction is key: with instructors, classmates, the interface, and via vicarious interaction.

• Online course design takes advantage of capabilities of the medium to improve learning (testing, discussion, materials).

• Courses are instructor led.

• Communications and community building are emphasized.

• Swift trust characterizes the online learning community.

• Distinctive characteristics of programs are highlighted to demonstrate improved learning.

• On-campus and online instruction achieve comparable learning outcomes, and the institution ensures the quality of learning in both modes with metrics tracking instructional methods, student constituencies, and class size.

Cost Effectiveness

• Institutions continuously improve services while reducing cost:

• Cost effectiveness models are tuned to institutional goals.

• Tuition and fees reflect cost of services delivery.

• Scalability, if an institutional objective, can be accommodated.

• Partnering and resource sharing are institutional strategies for reducing costs.

• Mission-based strategies for cost reduction are continuously formulated and tested.

• Intellectual property policies encourage cost-effective strategies.

Access

• All learners who wish to learn online have the opportunity and can achieve success:

• Diverse learning abilities are provided for (at-risk, disabilities, expert learners).

• The reliability and functionality of delivery mechanisms are continuously evaluated.

• Learner-centered courseware is provided.

• Feedback from learners is taken seriously and used for continuous improvement.

• Courses that students want are available when they want them.

• Connectivity to multiple opportunities for learning and service is provided.

Table 2. Sloan-C catalog of online programs

|

Area of Study |

Number of Programs |

|

Agriculture-Related |

8 |

|

Business and Management |

234 |

|

Computers |

149 |

|

Education |

111 |

|

Engineering |

57 |

|

Environmental-Related |

15 |

|

Health Care and Nutrition |

71 |

|

Humanities |

34 |

|

Language |

4 |

|

Law |

13 |

|

Liberal Arts |

34 |

|

Math |

7 |

|

Medicine |

22 |

|

Social Sciences |

54 |

|

Telecommunications |

40 |

Figure 1. The five quality pillars

Faculty Satisfaction

• Faculty achieve success with teaching online, citing appreciation and happiness:

• Faculty satisfaction metrics show improvement over time.

• Faculty contribute to and benefit from online teaching.

• Faculty are rewarded for teaching online and for conducting research about improving teaching online.

• Sharing of faculty experiences, practices, and knowledge about online learning is part of the institutional knowledge-sharing structure.

• There is a parity in workload between classroom and online teaching.

Table 3. Brief version of the quality framework

|

Goal |

Process/Practice |

Metric (for example) |

Progress Indices |

|

LEARNING EFFECTIVENESS |

|

||

|

The quality of |

Academic integrity and control |

Faculty perception surveys or |

Faculty report online |

|

learning online is |

reside with faculty in the same way |

sampled interviews compare learning |

learning is equivalent or |

|

demonstrated to be |

as in traditional programs at the |

effectiveness in delivery modes. |

better. |

|

at least as good as |

provider institution. |

|

|

|

the institutional |

\ |

Learner/graduate/employer focus |

Direct assessment of |

|

norm. |

|

groups or interviews measure |

student learning is |

|

|

learning gains. |

equivalent or better. |

|

|

COST EFFECTIVENESS |

|

||

|

The institution |

The institution demonstrates |

Institutional stakeholders show |

The institution sustains |

|

continuously |

financial and technical |

support for participation in online |

the program, expands |

|

improves services |

commitment to its online |

education. |

and scales upward as |

|

while reducing |

programs. |

|

desired, and strengthens |

|

costs. |

|

Effective practices are identified and |

and disseminates its |

|

Tuition rates provide a fair return to the institution and best value to learners. |

shared. |

mission and core values through online education. |

|

|

|

ACCESS |

|

|

|

All learners who |

Program entry and support |

Administrative and technical |

Qualitative indicators |

|

wish to learn |

processes inform learners of |

infrastructure provides access to all |

show continuous |

|

online can access |

opportunities, and ensure that |

prospective and enrolled learners. |

improvement in growth |

|

learning in a wide |

qualified, motivated learners have |

|

and effectiveness rates. |

|

array of programs |

reliable access. |

Quality metrics for |

|

|

and courses. |

|

information dissemination; learning resources delivery; tutoring services. |

|

|

FACULTY SATISFACTION |

|

||

|

Faculty are |

Processes ensure faculty |

Repeat teaching of online courses by |

Data from post-course |

|

pleased with |

participation and support in online |

individual faculty indicates approval. |

surveys show |

|

teaching online, |

education (e.g., governance, |

|

continuous |

|

citing appreciation |

intellectual property, royalty |

Addition of new faculty shows |

improvement: |

|

and happiness. |

sharing, training, preparation, rewards, incentives, and so on). |

growing endorsement. |

At least 90% of faculty believe the overall online teaching/learning experience is positive. |

|

|

|

Willingness/desire to teach additional courses in the program: 80% positive. |

|

|

STUDENT SATISFACTION |

|

||

|

Students are |

Faculty/learner interaction is |

Metrics show growing satisfaction: |

Satisfaction measures |

|

pleased with their |

timely and substantive. |

|

show continuously |

|

experiences in |

Surveys (see above) and/or |

increasing improvement. |

|

|

learning online, |

Adequate and fair systems assess |

interviews |

|

|

including |

course learning objectives; results |

|

Institutional surveys, |

|

interaction with |

are used for improving learning. |

Alumni surveys, referrals, |

interviews, or other |

|

instructors and |

|

testimonials |

metrics show |

|

peers, learning |

|

satisfaction levels are at |

|

|

outcomes that |

|

Outcomes measures |

least equivalent to those |

|

match |

|

|

of other delivery modes |

|

expectations, |

|

Focus groups |

for the institution. |

|

services, and |

|

|

|

|

orientation. |

|

Faculty/mentor/advisor perceptions |

|

Table 4. Effective practices matrix

|

|

Learning |

Cost Effectiveness |

Access |

Faculty |

Student |

|

|

Effectiveness |

|

|

Satisfaction |

Satisfaction |

|

Community |

Learning |

Consortia and |

Academic and |

Faculty |

Student |

|

|

community |

partnerships |

administrative services to enable community |

participation with new populations of students and interactive learning communities |

engagement in learning community |

|

|

Curriculum and |

Evaluation of |

Access to a |

Governance and |

Academic and |

|

Learning |

course design |

re/design, relating |

variety of |

quality control |

administrative |

|

Design |

and conduct |

costs and outcomes |

programs, courses, and learning resources |

support services |

|

|

Assessment, |

Evaluation of |

System-wide |

Access studies |

Opportunities |

Online channels |

|

Research, |

learning |

implementations |

and refinements |

for research and |

for lifelong |

|

Evaluation |

processes, outcomes, perceptions |

based on evaluation results |

|

publication |

affiliation with community |

|

Information |

Learning |

Strategic planning |

Technical |

Technological |

User-friendly |

|

Technology |

technology |

and accounting to enhance quality and reduce institutional and student costs |

infrastructure and training for users |

innovations to reduce faculty administrative workload |

interfaces |

• Significant technical support and training are provided by the institution.

Student Satisfaction

• Students are successful in learning online and are typically pleased with their experiences. Measurement of student attitudes finds that:

• Discussion and interaction with instructors and peers is satisfactory.

• Actual learning experiences match expectations.

• Satisfaction with services (advising, registration, access to materials) is at least as good as on the traditional campus.

• Orientation for how to learn online is satisfactory.

• Outcomes are useful for career, professional, and academic development.

effective practices

“To help learning organizations continually improve quality, scale, and breadth,” Sloan-C members share effective practices in an online knowledge center that helps people implement practices that work. Submissions to the site become eligible for annual awards when they are reviewed and approved by Sloan-C editors for effective practices according to these criteria:

• Innovation: the practice is inventive or original.

• Replicability: the practice can be implemented in a variety of learning environments.

• Potential impact: the practice would advance the field if many adopted it.

• Supporting documentation: the practice is supported with evidence of effectiveness.

• Scope: the practice explains its relationship with other quality elements.

The matrix in Table 4 indicates some of the relationships among the quality elements; the left-hand vertical column lists values common to each of the pillars.

directions for research and development

As online education becomes part of the fabric of higher education, and combinations of face-to-face and online learning constitute the norm, the rate of technological change collides with an academic tradition that proceeds at a sometimes slow rate of consensus building (NRC, 2002). Many schools report that they are experiencing the transformative effects of ALN. The University of Maryland University College, the State University of New York, the University of Central Florida, Penn State, the University of Massachusetts, and more have witnessed a positive “spillover effect” that communicates advances in online learning to face-to-face learning (Bourne & Moore, 2004). These positive effects include support and information services designed for online students which help place-based students as well, redesigned courses and programs that undergo scrutiny and refinement by peers, information technologists, course designers, and content experts.As advances continue, Hiltz,Arbaugh, and Benbunan-Fich (2004) propose that we can learn to measure learning across classes, courses, institutions, organizations, and cultures. Hiltz and colleagues recommend that research models include the characteristics cited in this excerpt from their paper:

1. the technology (in particular, the media mix);

2. the group (course or class), and the organizational setting (college or university), which define the context in which the technology is used;

3. the instructor; and

4. the individual student. (Hiltz et al., 2004)

Every quality area calls for standards, norms, and benchmarks to be shared among academic institutions, corporations, foundations, and government. Thus, Sloan-C engages in dialog with the corporate training community that has developed in parallel, but separately, from the academic community to explore the possibilities for degree-oriented, industry-specific education for entire industries: “Whether we call the phenomenon ‘online learning’ or ‘e-learning’, our hypothesis is that the Sloan Consortium (Sloan-C) can meld its accumulated knowledge with corporate knowledge to improve the quality of learning in both sectors” (The Sloan Consortium, 2003c). In particular, practitioners want to learn how to encourage higher-order learning online, how to adapt technology for the continuously improving interaction, how to use assessment to mainstream best practices, and how to optimize learning by combining ALN and face-to-face learning.

The conversation with which ALN began a decade ago continues today as a global conversation, aiming for much greater access to learning, and enacting the visionary spirit. Alfred P. Sloan claimed for his legacy in his own life story, Adventures of a White Collar Man:

The greatest real thrill that life offers is to create, to construct, to develop something useful.Too often we fail to recognize and pay tribute to the creative spirit. It is that spirit that creates our jobs…There has to be this pioneer, the individual who has the courage, the ambition to overcome the obstacles that always develop when one tries to do something worthwhile, especially when it is new and different. (Sloan & Sparkes, 1941, pp. 127, 140-141)

key terms

Access: The quality principle that is the fundamental motivation for online learning, access means that people who are qualified and motivated can obtain affordable, quality education in the discipline of choice.

Asynchronous Learning Networks (ALN): Technology-enabled networks for communications and learning communities.

Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI): A process that measures progress towards goals, using metrics and feedback from stakeholders for continuous improvement.

Cost Effectiveness: The quality principle that assures the institutional mission is conveyed online, affordably for the institution and for learners.

Effective Practices: Online practices that are replicable and produce positive outcomes in each of the pillar areas. The Sloan-C site is http://www.sloan-c.org/effective.

Faculty Satisfaction: The quality principle that recognizes faculty as central to quality learning.

Five Pillars: The Sloan-C quality elements of learning effectiveness, cost effectiveness, access, faculty satisfaction, and student satisfaction.

Learning Effectiveness: The quality principle that assures that learning outcomes online are at least equivalent to learning outcomes in other delivery modes.

Quality Framework: A work in progress that assesses educational success in terms of continuous quality improvement.

Student Satisfaction: The quality principle that measures student perceptions and achievement as the most important predictors of lifelong learning.