Propylon

The first case study [54,55] is relative to the open area (so called Piazzale Inferiore 10) directly connected to the building of power itself, the Villa, and linked with the facilities of the village, in a period between the seventeenth and fifteenth century BC (Figure 1.2).

The excavations of the summer 2006 revealed on the north side the foundation of a very narrow and elongated rectangular room that served as a hub for the road from the village and therefore constituted a real propylon, whose function of monumental vestibule is confirmed by the large threshold still recognizable in situ, according to the constructive concept input of the precinct with an elegant entrance, popular choice in the Neopalatial period [56, 57].

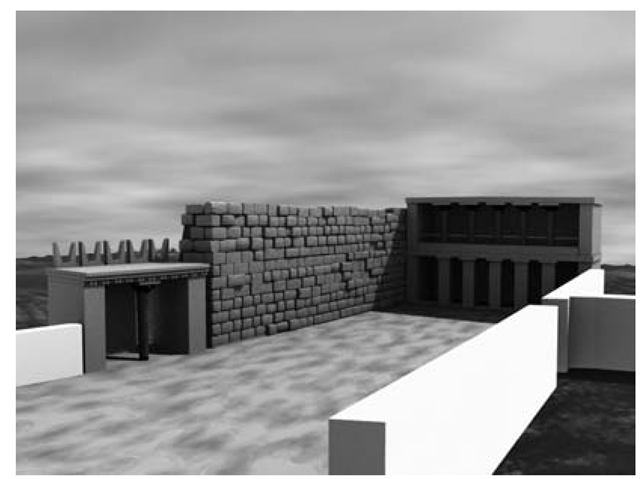

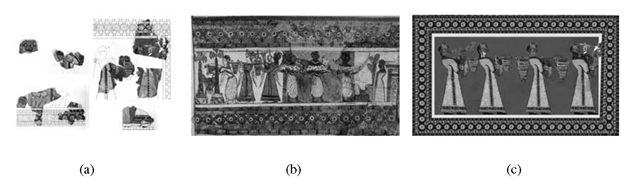

FIGURE 1.3

3D reconstructive model of the open area between the village and the Villa with the virtual reconstruction of the Propylon, the facade of the Bastion and the Stoa.

The need to consider the overall organization of this sector of the monumental complex has been addressed by the 3D modeling technology, with the application of a philological approach, based on a thorough investigation of the fundamental characteristics of Minoan architecture [58,59] and of the repertoires represented on stone vessels [48] and on the frescoes [61,62], all contemporary to the structures under study. In the middle of the north side of the open area stood the propylon which had its monumental face, probably, provided with a column, right-facing the open space and the Villa itself. The rear elevation provided a simple unaligned entrance, oriented to a gently sloping ramp that represented the main road of the village. The review of the archaeological evidence allowed reconstruction of the east side of the area, a sort of small stoa or porch [56, 57], with a second floor veranda facing the great paved road to the sea. In this case some artifacts documenting the characteristics of Minoan public and private buildings were fundamental (Figure 1.5.1).

House of the Razed Rooms

The other case study is represented by the so-called House of the Razed Rooms [42] (Figure 1.4). This house, built and used during the fourteenth century BC (late Minoan IIIA2), located in the north eastern part of the settlement, north of the Villa, was so deeply damaged by many subsequent activities that it became indispensable trying to create a virtual model to analyze its architectural phases [63]. Discovered by Federico Halbherr in 1911, the House of Razed Rooms, built on two superimposed terraces, takes its name by the razing of the walls of the upper terrace, and the covering and the re-qualification of the structures of the lower one, carried out when a new plan of this area was designed in the second half of the fourteenth century, after the fall of the Knossos palace. After the excavation of 1991, when only the southern part of the building was uncovered, in 1983 V. La Rosa [64] completed the exploration of the house, discovering the complete plan with a main L-shaped corridor (no. 2) with two groups of modular rooms (no. 5, 6, 7 in the western side and no. 1, 3, 4 in the northern part). The corridor 2 had a floor of 1.50 m higher than the other six rooms, that were accessible through trapdoor from the top. The entire building had a length of 20.10 m in north/east-south/west sense and a surface of 180 m2; the walls had a thickness of 0.80-0.90 m with foundations on the rock. The plan, the thickness of the walls, and the absence of a direct connection between corridor 2 and the other rooms seem to suggest that probably this building did not have residential functions. Furthermore, the subdivision of the space in the same modular unities [65] is a feature, present in some contemporary buildings of Greece like Gla and Mycenae, that has to be interpreted as the mark of structures used as warehouses. In this context, it is possible to identify the two groups of rooms 1, 3, 4, and 5-7 of the House of the Razed Rooms as silos used probably for the long conservation of cereals and legumes [66].

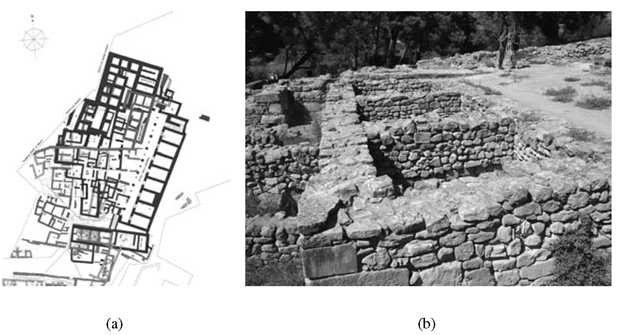

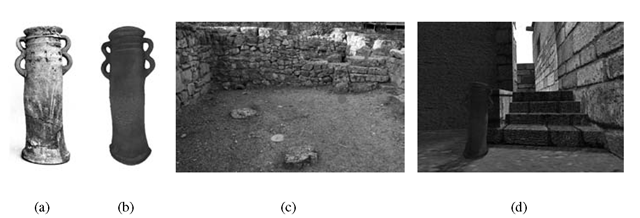

FIGURE 1.4

Haghia Triada, village: (a) multilayered plan; (b) House of the Razed Rooms in the current preservation state, view from south west.

The virtual model of the building (Figure 1.5) was very useful for many reasons [63], such as the possibility of producing two different models of the House of the Razed Rooms, one of the actual state of the building (Figure 1.5(a)), as to create a digital replica of the monument to be used for virtual museum politics, and a second one presenting a picture of the House at the moment of its use (Figure 1.5(b)).

VAP House

Another evidence, datable to the Late Palatial period, is the monumental mansion with several building phases, that has been identified with the house of the local authority, called by Italian archaeologists “Casadei Vani Aggiunti Progressivamente” (VAP House, Figure 1.5.3) [47,67]. The main peculiarity of this building is how it was progressively enlarged by means of single rooms. This process involved the transformation of the original outer walls into partition walls. Seven subsequent building phases, with the construction of a second floor, the progressive adjunction of rooms and open spaces, can be distinguished between LM IIIA2 early and LM IIIB. At the time of the abandonment of the site in LM IIIB, VAP House was a substantial building, with twelve rooms and one small court on the ground floor, and at least five more rooms on the first floor. The ground floor measured about 320 m2, and the total extension, including the upper floor, was about 450 m2. The few finds from the House (mostly some pithoi and a few other vessels) suggest that it was abandoned in a nonviolent way and systematically emptied. A pyxis, a fragmentary pithos, and a clay stand of “snake tube” type were found in room A [68]. The latter was placed near the outer door of the room, beside the first step of the stair, and was probably used to hold cultic offerings.

The construction of room A, in the fifth building phase, involved a functional reassessment of the lower floor space that was related to the new layout of the principal North-South road of the settlement, and to the creation of the largest open area of Haghia Triada, the so-called Agora.

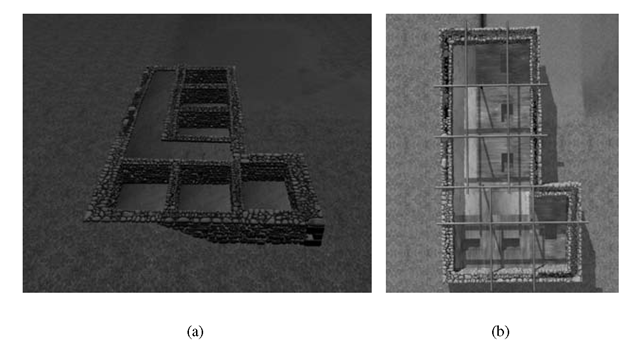

FIGURE 1.5

(a) Virtual replica of the House of Razed Rooms; (b) architectural study of the wooden floor with trapdoors and of the roof beams system on the virtual model.

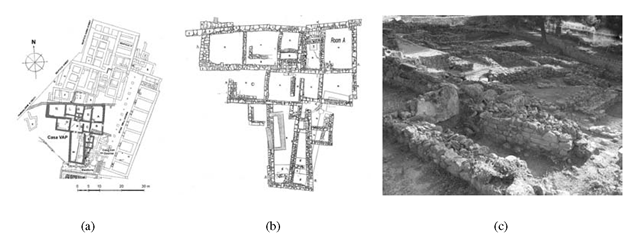

FIGURE 1.6

Haghia Triada, village: (a) Multilayered plan; (b) detailed plan of the VAP House; (c) VAP House in the current preservation state, view from south west.

FIGURE 1.7

Vap House, Room A: (a) Fragments of the procession fresco; (b) procession scene on the Haghia Triada Sarcophagus; (c) virtual color reconstruction of the procession fresco.

It probably became the most important living room of the House, due to its large dimensions (6.80 x 4.90 m) and its proximity to the Agora. The ceremonial function of room A is confirmed by the frescoes, representing processions with people taking offerings and animals for sacrifice [67]. They belong to a figurative cycle, endowed with a strong symbolical character, which was probably intended to mark the beginning of an entirely new era in the political history of the settlement, when it became the capital of a small state in south-central Crete [43]. Virtual reconstruction is a valuable visualization tool when a complex and multiphased architecture has to be documented. It provides a graphical support to reason about the building and to visually access hypotheses about the appearance in the several construction phases. The reconstruction of the visible walls, derived from the graphic and photographic documentation available, offers a global picture of the entire house in its last phase before abandonment. To recreate a visual image of its ancient life explains the past by means of experiencing it [46]. The digital restoration of the procession fresco (Figure 1.7), and the re-creation of the ceremonial ambient of room A, with the location of the snake tube (Figure 1.8) in its original position, is another useful interpretative tool. The virtual model of the building, derived from the graphic and photographic documentation available, offers a global picture of the entire house as it is conserved now, including the fresco in room A and the snake tube. The virtual reconstruction (Figure 1.5.3) is intended to show the hypotheses about the state of the building in its several phases. To this aim the rooms have been modeled on different 3D layers: the user may choose the epoch and only the layer with the structures present in that epoch will be visualized. This interactive use greatly supports discussion and formulation of the alternative reconstruction choices. The building model has been completed with a minimal set of objects and decoration. In particular, a 3D model of a snake tube has been realized from photographic references of the snake tube found in room A (Figure 1.8. The modeling has been done generating the tube as a revolution solid, deformed and completed with snake-like handles (Figure 1.8(b)). In addition to the 3D reconstruction, a parallel virtual restoration activity has been performed on the very fragmentary remains of the fresco that was once on the wall of room A (Figure 1.7).

FIGURE 1.8

(a) The snake tube from the room A; (b) 3D model of the snake tube obtained with Image Base 3D modeling technique; (c) Room A, to the right the stairway to room B and the location point of the snake tube, to the left the wall with the procession fresco, view from north. (d) virtual model of the Room A with the snake tube in its original position.

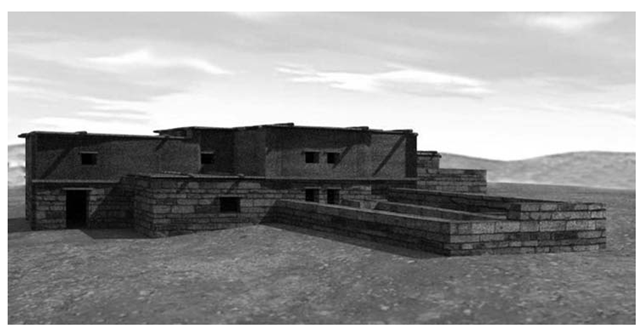

FIGURE 1.9

3D reconstructive model of the VAP House, view from south west.

Polizzello Mountain, Sicily

The indigenous settlement of Polizzello in the territory of Mussomeli (Caltanissetta) is situated on the top of an 877 m high, precipitous mountain that is almost completely encircled by the valleys created by the watercourse of two tributaries of the Platani River: the Fiumicello to the west and the Belici to the east. Strategically located in the very core of Sikania, the mountainous area of central Sicily described by Greek historians that corresponds to the modern territory of Caltanissetta and Agrigento, bordered to the east by the Salso River and to the west by the Platani river, this settlement has for the last 25 years been one of the key sites for the interpretation of the socio-political dynamics of the indigenous communities of central Sicily from the eighth to the late sixth century BC. The archaeological importance and richness of the area has always been well known to the local people who lived in the modern village of Polizzello. After several isolated cases of discovery of materials on the mountain, in 1926, P. Orsi and his collaborator R. Carta began an excavation that clarified the potential importance of this settlement within the region. In the course of these explorations a branch of the necropolis of the late eighth and seventh centuries BC, the settlement area and a shrine of Greek-indigenous type were found. After a long gap, the Superintedence of Agrigento restarted excavations between 1984 and 1990, focusing on the upper plateau, the so-called acropolis, still unknown. On the acropolis four buildings interpreted as open shrines (Sacelli), A, B, C, D, and enclosed by a kind of Temenos were identified (Figure 1.10(a)). Another larger circuit wall was also discovered, and interpreted as a fortification. Although the excavations were not all completed, the preliminary results gave the impression that the site was a very important cult place that had been active between the mid eighth and mid sixth centuries BC. The large assemblages of indigenous and Greek vessels, the bone, amber, ivory and faience items, the iron and bronze weapons, the bronze figurines of worshippers and their location in votive deposits inside the four buildings, defined the cultural richness and complexity of the indigenous community, its external interactions, and the great ritual relevance of the acropolis area. Between 2000 and 2006, the Superintendence of Caltanissetta and the University of Catania carried out a new systematic excavation project on the acropolis, with the aim of completing the previous explorations, definitively defining the different phases of occupation, principally the earliest, and restoring the archaeological area so that it could be opened to the public [69-71].

Buildings A, B, C, D, E

One of the most important aspects of the acropolis excavation was the completion of work on buildings A, B, C, D (Figures 1.11(a), 1.11(b)). They basically were circular or irregular precincts with entrance to the south, raised up with stone blocks in double curtain technique (emplecton) and paved with pressed earth floors. Inside several pieces of complement furniture were found as altars, hearths, and benches. Of great importance were the two buildings at the northern end of the acropolis, A and B, that performed different functions in the religious liturgy of the sanctuary activity. Building A, with a diameter of 8 m, probably kept the wooden statue of the deity, now disappeared, set on a rock base at the center, to which were offered votive gifts like vessels, iron weapons, and amber and bone beads, dated to the mid seventh century BC, accompanied by traces of animal sacrifices.

The new excavations were especially concerned with building B, where previous exploration had focused on the ground layer covering the structures. The building B, built shortly after A and partially leaning upon it, with a diameter of about 10 m, was the real treasure of the sanctuary, where all offers to the gods, the most valuable and varied, were kept at end of ceremonies that involved community meals and libations. Inside it, a pressed earth floor, a hearth, a circular bench running along the walls, a recess and an altar were revealed. A small statue of an ithyphallic warrior of indigenous type was found on the “altar” together with a set of astragaloi, nine of bone and one of lead. The circular bench may have been used as seating for the participants in the rites, while the recess seems to have been used to isolate and hold specific depositions.

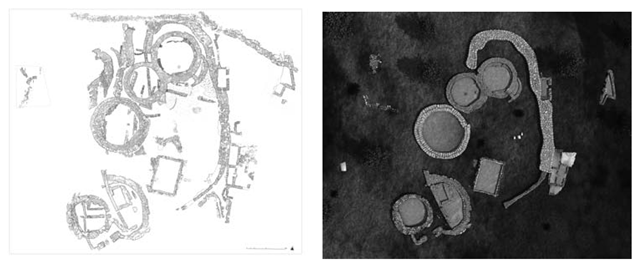

FIGURE 1.10

(a) Plan of the sacred area on the Acropolis of Polizzello Mountain; (b) virtual replica of sacred area on the Acropolis of Polizzello Mountain.

Seventeen deposits of a total of 193 objects of the sixth century BC were found on the floor, simply placed and not hidden or covered, mostly in the northern part of the building. At least three groups of depositions can be distinguished. Pottery from the depositions includes a selected repertoire of the so-called Polizzello-Sant’Angelo Muxaro production: trefoil mouthed oinochoai, dippers, and cups. Large vessels such as pithoi, basins, and kraters imitate Greek prototypes. Some specimens of cups with terracotta figurines of a hut with animals inside are very significant on account of their rarity. Several Greek vessels were also found, mostly kylikes, ionic cups, kotylai, and a few kraters. In terms of metal items, the iron spears, sometimes of huge dimensions, are the most important items, followed by bronze arrows. Swords are entirely absent, and there are only a few daggers. Iron tools such as sickles and hoes are attested; axes are present only in bronze miniature versions. Bronze ornaments, such as bracelets, finger-rings, chains, and bronze foils are also represented as well as ivory, amber, and bone beads related to jewelery items. Furthermore, six regular-shaped lead ingots were recovered. Some of the most significant finds were an ivory and amber plate that was incised with a vegetal motif, and was probably part of the decoration of the lid of a wooden box; two sub-daedalic idols made of ivory; a couple of bronze dolphin laminae; and a bronze helmet of Cretan type decorated with a figure of hoplite. Although the previous excavations conducted in the area of buildings C and D had been very thorough, further investigation inside building D revealed a few vessels and several exotic items, mostly amber and ivory beads, dated to the seventh and sixth centuries BC. Furthermore, a second large building, called E (Sacello E), was found in the north western part of the acropolis, close to building A. Its 14.70 m diameter and megalithic construction technique is unique in Sicilian contexts, and it must therefore have been a structure of fundamental importance within the sacred area. This huge building may have been used at least through three different phases: in the second half of the eighth century BC, at the beginning of the seventh century BC, and between the end of the seventh and the beginning of the sixth century BC (Figure 1.12).

FIGURE 1.11

Polizzello Acropolis: (a) Buildings A, B, and E, view from south; (b) Building D view from north; (c) Room III, view from south east; (d) Temenos House, view from east; (e) East House, digital ortophotograph.

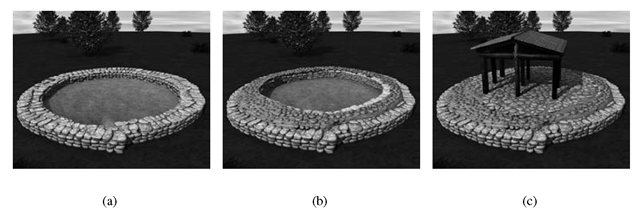

FIGURE 1.12

Building E: (a) phase I, second half of the eighth century BC; (b) phase II, beginning of the seventh century BC; (c) phase III, between the end of the seventh and the beginning of the sixth century BC.