Crown and Root Development

Dental development can be considered to have two components: (1) the formation of crowns and roots and (2) the eruption of the teeth. Of these two, the former seems to be much more resistant to environmental influences; the latter can be affected by caries and tooth loss.11,12

After the crown of the tooth is formed, development of the root portion begins. At the cervical border of the enamel (the cervix of the crown), cementum starts to form as a root covering of the dentin. The cementum is similar in some ways to bone tissue and covers the root of the tooth in a thin layer. In the absence of a succeeding permanent tooth, the root of the primary tooth may only partially resorb. When root resorption does not follow the usual pattern, the permanent tooth cannot emerge or is otherwise kept out of its normal place. In addition, the failure of the root to resorb may bring about prolonged retention of the primary tooth. Although mandibular teeth do not begin to move occlusally until crown formation is complete, their eruption rate does not closely correlate with root elongation. After the crown and part of the root are formed, the tooth penetrates the alveolar gingiva and makes its entry (emergence) into the mouth.

Further formation of the root is considered to be an active factor in moving the crown toward its final position in the mouth. The process of eruption of the tooth is completed when most of the crown is in evidence and when it has made contact with its antagonist or antagonists in the opposing jaw. The root formation is not finished when the tooth emerges; however, the formation of root dentin and cementum continues after the tooth is in use. Ultimately, the root is completed with a complete covering of cemen-tum. Additional formation of cementum may occur in response to tooth movement or further eruption of the teeth. Also, cementum may be added (repaired) and/or resorbed in response to periodontal trauma from occlusion. The covering of cementum of the permanent teeth is much thicker than that of the primary teeth.

The Dentitions

The human dentitions are usually categorized as being primary, mixed (transitional), and permanent dentitions. The transition from the primary/deciduous dentition to the permanent dentition is of particular interest because of changes that may herald the onset of malocclusion and provide for its interception and correction. Thus of importance for the practitioner are the interactions between the morphogenesis of the teeth, development of the dentition, and growth of the craniofacial complex.

Prenatal/Perinatal/Postnatal Development

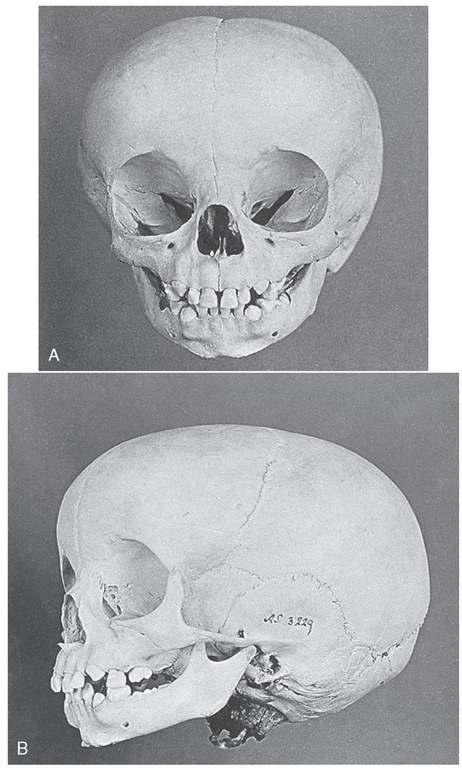

The first indication of tooth formation occurs as early as the sixth week of prenatal life when the jaws have assumed their initial shape; however, at this time the jaws are rather small compared with the large brain case and orbits. The lower face height is small compared with the neurocranium (Figure 2-6). The mandibular arch is larger than the maxillary arch, and the vertical dimensions of the jaws are but little developed. When the jaws close at this stage in the development of the dentition, they make contact with the tongue, which in turn makes contact with the cheeks. The shape of the prenatal head varies considerably, but the relative difference between the brain case, orbits, and lower face height remains the same. All stages of tooth formation fill both jaws during this stage of development.

Development of the Primary Dentition

Considerable growth follows birth in the neurocranium and splanchnocranium. Usually at birth, no teeth are visible in the mouth; however, occasionally, infants are born with erupted mandibular incisors.

Figure 2-6 Neonatal skull showing large brain case and orbits; the neurocranium is larger than the splanchnocranium, which contains the jaws and all the developing teeth.

Development of both primary and permanent teeth continues in this period, and jaw growth follows the need for additional space posteriorly for additional teeth. In addition the alveolar bone height increases to accommodate the increasing length of the teeth. However, growth of the anterior parts of the jaws is limited after about the first year of postnatal life.

SEQUENCE OF EMERGENCE OF PRIMARY TEETH

The predominant sequence of eruption of the primary teeth in the individual jaw is central incisor (A), lateral incisor (B), first molar (D), canine (C), and second molar (E), as seen in Table 2-1. Variations in that order may be the result of reversals of central and lateral incisors or first molar and lateral incisor, or eruption of two teeth at the same time.

Investigations of the chronology of emergence of primary teeth in different racial and ethnic groups show considerable variation,7 and little information is available on tooth formation in populations of nonwhite/non-European ancestry.14 World population differences in tooth standards suggest that patterned differences may exist that in fact are not large.14 Tooth size, morphology, and formation are highly inheritable characteristics.15 Few definitive correlations exist between primary tooth emergence and other physiological parameters such as skeletal maturation, size, and sex.16

EMERGENCE OF THE PRIMARY TEETH

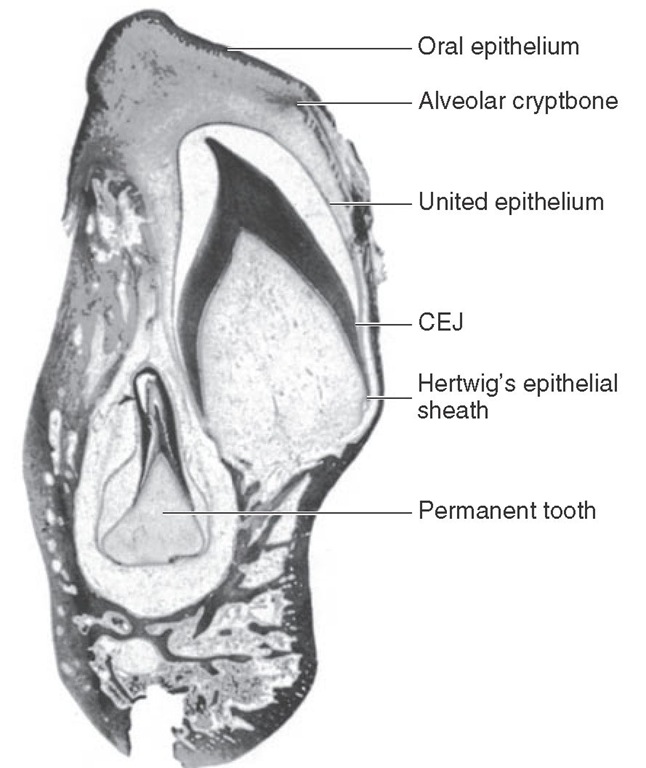

At about 8 (6 to 10) months of age, the mandibular central incisors emerge through the alveolar gingiva, followed by the other anterior teeth, so that by about 13 to 16 months, all eight primary incisors have erupted (see Table 2-1). Then the first primary molars emerge by about 16 months of age and make contact with opposing teeth several months later, before the canines have fully erupted. Passage through the alveolar crest (Figure 2-7) occurs when approximately two thirds of the root is formed,17 followed by emergences through the alveolar gingiva into the oral cavity when about three fourths of the root is completed.18 The emergence data are consistent with those of Smith.14

Figure 2-7 Section of mandible in a 9-month-old infant cut through an unerupted primary canine and its permanent successor, which lies lingually and apically to it. The enamel of the primary canine crown is completed and lost because of decalcification. Root formation has begun. CEJ, Cementoenamel junction.

The primary first molars emerge with the maxillary molar tending most often to erupt earlier than the mandibular first molar.19 Some evidence shows a difference by gender for the first primary molars, but no answer is available for why the first molar has a different pattern of sexual dimorphism.7

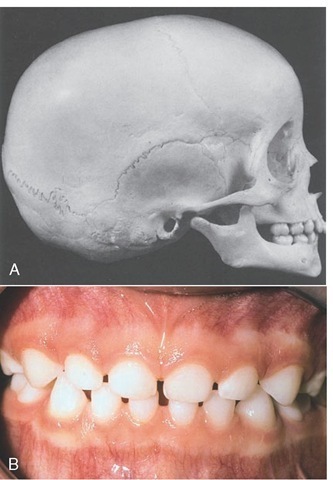

The primary maxillary canines erupt at about 19 (16 to 22) months (Figure 2-8), and the mandibular canines erupt at 20 (17 to 23) months. The primary second mandibular molar erupts at a mean age of 27 (23 to 31, boys) (24 to 30, girls) months, and the primary maxillary second molar follows at a mean age of 29 (25 to 33 ± 1SD) months. In Figures 2-8, A and B, the first molars are in occlusion.

Neuromuscular Development

A mature neuromuscular controlled movement of the mandible requires the presence and articulation of the teeth and proprioceptive input from the periodontium. Thus, the contact of opposing first primary molars is the beginning of the development of occlusion and a neuromuscular substrate for more complex mandibular and tongue functions.

Figure 2-8 Skull of a child about 20 months of age. A, View showing all incisors present and erupting canines. B, Lateral view. First primary molars are in occlusion; mandibular second molars are just emerging opposite the already erupted maxillary molar.

Primary Dentition

The primary/deciduous dentition is considered to be completed by about 30 months or when the second primary molars are in occlusion (Figure 2-9). The dentition period includes the time when no apparent changes occur intraorally (i.e., from about 30 months to about 6 years of age).

The form of the dental arch remains relatively constant without significant changes in depth or width. A slight increase in the intercanine width occurs about the time the primary incisors are lost, and an increase in size in both jaws in a sagittal direction is consistent with the space needed to accommodate the succedaneous teeth.

FIGURE 2-9 A, Skull of child 4 years old with completed primary Jentition. B, Completed primary dentition. Note the incisal wear.

An increase in the vertical dimension of the facial skeleton occurs as a result of alveolar bone deposition, condyle growth, and deposition of bone at the synchondrosis of the basal part of the occipital bone and sphenoid bones, and at the maxillary suture complex.20 The splanchnocranium remains small in comparison with the neurocranium. The part of the jaws that contain the primary teeth has almost reached adult width. At the first part of the transition period, which occurs at about age 8, the width of the mandible approximates the width of the neurocranium. The dental arches are complete, and the occlusion of the primary dentition is functional.

Transitional (Mixed) Dentition Period

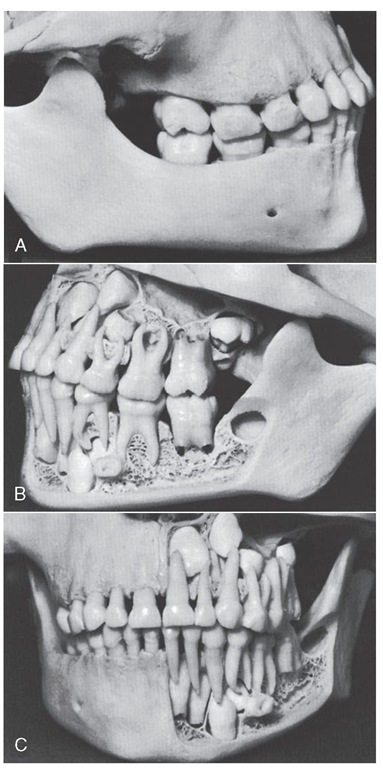

The first transition dentition begins with the emergence and eruption of the mandibular first permanent molars and ends with the loss of the last primary tooth, which usually occurs at about age 11 to 12. The initial phase of the transition period lasts about 2 years, during which time the permanent first molars erupt (Figures 2-10 and 2-11), the primary incisors are shed, and the permanent incisors emerge and erupt into position (Figure 2-12). The permanent teeth do not begin eruptive movements until after the crown is completed. During eruption, the permanent mandibular first molar is guided by the distal surface of the second primary molar. If a distal step in the terminal plane is evident, malocclusion occurs (see Figure 16-5).

Figure 2-10 Primary dentition with first permanent molars present. Maxillary arch. B, Mandibular arch.

Loss of Primary Teeth

The premature loss of primary teeth because of caries has an effect on the development of the permanent dentition21 and not only may reflect an unfortunate lack of knowledge as to the course of the disease but also establishes a negative attitude about preventing dental caries in the adult dentition. Loss of primary teeth may lead to lack of space for the permanent dentition. It is sometimes assumed by laypersons that the loss of primary teeth, which are sometimes referred to as baby teeth or milk teeth, is of little consequence because they are only temporary. However, the primary dentition may be in use from age 2 to 7 or older, or about 5 or more years in all. Some of the teeth are in use from 6 months until 12 years of age, or 11.5 years in all. Thus these primary teeth are in use and contributing to the health and well-being of the individual during the first years of greatest development, physically and mentally.

Figure 2-11 Same child as in Figure 2-10. A, Right side. B, Left side showing position of first permanent molars and empty bony crypt of developing second molar lost during preparation of the specimen. C, Front view showing right side with bone covering roots and developing permanent teeth, and left side with developing anterior permanent teeth.

Figure 2-12 Eruption of the permanent central incisors. Note the incisal edges demonstrating mamelons and the width of the emerging incisors.

Premature loss of primary teeth, retention of primary teeth, congenital absence of teeth, dental anomalies, and insufficient space are considered important factors in the initiation and development of an abnormal occlusion. Premature loss of primary teeth from dental neglect is likely to cause a loss of arch length with a consequent tendency for crowding of the permanent dentition.