Internal Surface of the Mandible

Observation of the mandible from the rear shows that the median line is marked by a slight vertical depression, representing the line of union of the right and left halves of the mandible, and that immediately below this, at the lower third, the bone is roughened by eminences called the superior and inferior mental spines, or genial tubercles (see Figures 14-15 and 14-34, C).

The internal surface of the body of the mandible is divided into two portions by a well-defined ridge, the mylo-hyoid line. It occupies a position closely corresponding to the lateral oblique ridge on the surface. It starts at or near the lowest part of the mental spines and passes backward and upward, increasing in prominence until the anterior portion of the ramus is reached; there, it smoothes out and gradually disappears (see Figures 14-14 and 14-34, C).

This ridge is the point of origin of the mylohyoid muscle, which forms the central portion of the floor of the mouth. Immediately posterior to the median line and above the anterior part of the mylohyoid ridge a smooth depression, the sublingual fossa, may be seen. The sublingual gland lies in this area.

A small, roughened oval depression, the digastric fossa, is found on each side of the symphysis immediately below the mylohyoid line and extending onto the lower border. Toward the center of the body of the mandible, between the mylohyoid line and the lower border of the bone, a smooth oblong depression is located, called the submandibu-lar fossa. It continues back on the medial surface of the ramus to the attachment of the lateral pterygoid muscle. The submandibular gland lies within this fossa.

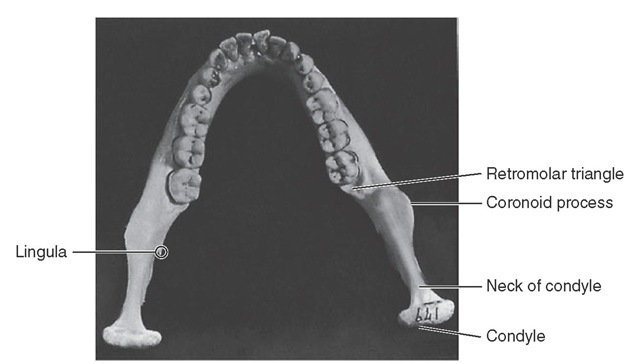

The mandibular foramen is located on the medial surface of the ramus midway between the mandibular notch and the angle of the jaw and also midway between the internal oblique line and the posterior border of the ramus. The mandibular canal begins at this point, passing downward and forward horizontally.

The anterior margin of the foramen is formed by the lingula, or mandibular spine, which gives attachment to the sphenomandibular ligament. Coming obliquely downward from the base of the foramen beneath the lingula is a decided groove, the mylohyoid groove. Behind this groove toward the angle of the mandible, a roughened surface for the attachment of the medial pterygoid muscle may be seen.

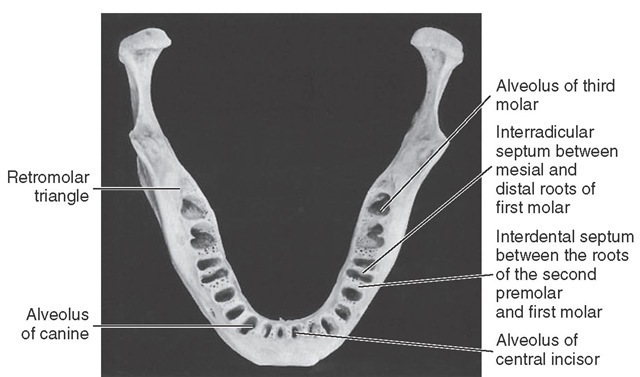

ALVEOLAR PROCESS

The border of the alveolar process outlines the alveoli of the teeth and is very thin at its anterior portion around the roots of the incisor teeth but thicker posteriorly where it encompasses the roots of the molars. The alveolar process, which comprises the superior border of the body of the mandible, differs from the same process in the maxillae in one very important particular: it is not as cancellous, and instead of the facial plate’s being relatively thin, it is equally as heavy as the lingual plate. Although the bone over the anterior teeth, including the canine, is very thin and may be entirely missing over the cervical portion of the root, the bone that does cover the root is the compact type.

The inferior border of the mandible is strong and rounded and gives to the bone the greatest portion of its strength (see Figure 14-15).

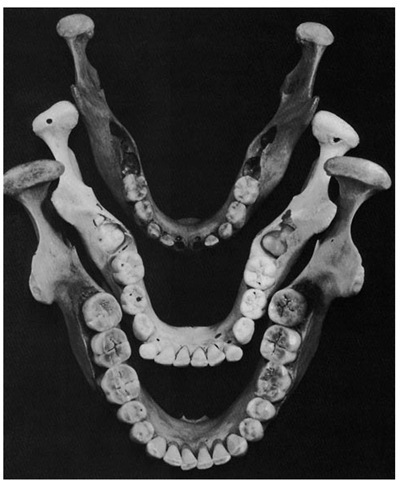

When one looks down on the mandible from a point above the alveoli of the first molars (see Figure 14-18), it can be noticed that although the alveolar border may be thinner anteriorly than posteriorly, the body of the bone is uniform throughout. The lines of direction of the posterior alveoli are inclined lingually to conform to the lingual inclination of the teeth when they are in position. The anterior teeth, of course, have their alveoli tipped labially; therefore when one looks down on the mandible from above the alveolar process, more of the bone may be seen lingual to the anterior teeth than lingual to the posterior teeth. In contrast, posteriorly, more of the bone may be seen buccal to the teeth than lingual. Therefore the outline of the arch of the teeth does not correspond to the outline of the arch of the bone. The dental arch is narrower posteriorly than the mandibular arch.

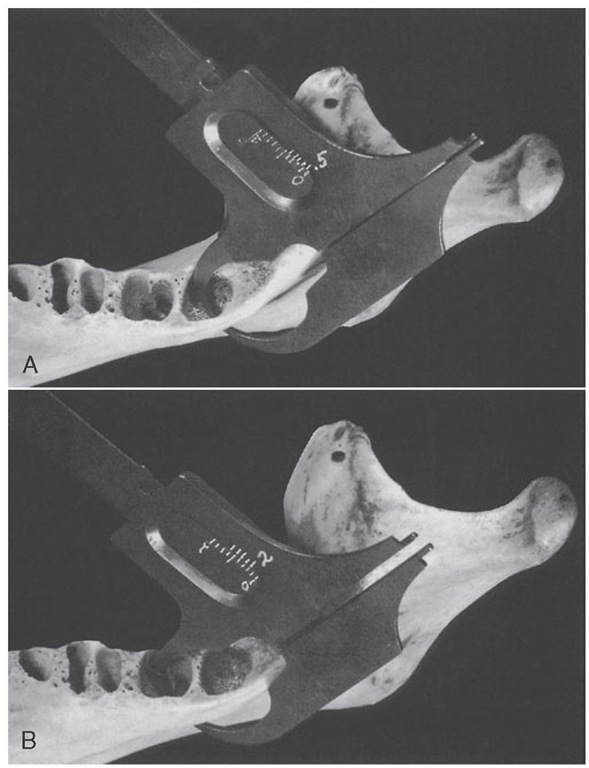

The lingual walls of the alveoli of the second and third molars are relatively thin near the bottoms of the sockets, although the bone near the periphery is somewhat thicker and very compact. If a specimen of the mandible from which the third molar has been removed is held up to the light, the bone at the bottom of the socket is so thin that light will penetrate it. This thinness of bone is consistent with the submandibular fossa below the mylohyoid ridge (see Figure 14-15; Figure 14-22, A and B; and Figure 14-24).

The bone buccal to the last two molars is very heavy and thick, being reinforced by the external oblique ridge. Posterior to the third molar a triangular shallow fossa is outlined; it is called the retromolar triangle (Figure 14-17). The cortical plate over this fossa is not as heavy as the bone surrounding it, and it is more cancellous under the thin cortical plate covering it.

ALVEOLI

The first alveolus right or left of the median line is that of the first, or central, incisor. The periphery of the alveolus often dips down lingually and labially and exposes the root for part of its length. This arrangement makes an interdental spine out of the interdental septum separating the alveolus of the mandibular central incisors. The central incisor alveolus is flattened on its mesial surface and is usually somewhat concave distally to accommodate the developmental groove on the root (see Figures 14-18 and 14-19).

The alveolus of the mandibular second, or lateral, incisor is similar to that of the central incisor. It usually has the following variations: the socket is larger and deeper to accommodate a larger and longer root; the periphery does not dip down as far on the lingual surface but may dip more on the labial aspect of the tooth, exposing more of the root of the lateral incisor. The interdental septum extends up just as high between the teeth as that between the central incisors.

The canine alveolus is quite large and oval and, of course, deep to accommodate the root of the mandibular canine. The lingual plate is stronger and much heavier than that over the alveoli just described, although the thin labial plate may thin out at its edges and expose just as much of the canine root on the labial side. The labial outline of the alveolus is wider than the lingual outline, and the mesial and distal walls of the sockets are irregular to accommodate developmental grooves, both mesially and distally, on the canine root (see Figures 14-18 and 14-20).

The alveoli of the first and second premolars are similar in outline. The outline is smooth and rounded, although the dimensions are greater buccolingually than mesiodistally. The alveolus of the second premolar is usually somewhat larger than that of the first premolar. The buccal plate of the alveoli is relatively thin, but the lingual plate is heavy; the interdental septum has become heavier at this point compared with the interdental septa found between the anterior teeth. The interdental septum between the canine and first premolar is relatively thin, although uniform in outline. The septum between the first premolar and second premolar is nearly twice as thick.

Figure 14-17 View of mandible from above.

Figure 14-18 Alveolar process of the mandible showing alveoli.

Figure 14-19 Closeup view of one of the three separate divisions of the mandibular alveoli (as shown in Figures 14-19, 14-20, and 14-21). This picture indicates the relative sizes and shapes of the incisors for comparison with other mandibular teeth.

Figure 14-20 This view of the mandibular alveoli includes the canine, the first and second premolars, and a clear view of the mandibular first molar alveoli. Note the excellent design for the anchorage of first molar roots. Apparently, the blood supply for the interseptal bone lessens as anterior teeth are approached. The apical portion of the canine alveolus displays the single opening in the bone for the blood and nerve supply to the tooth pulp.

Progressing posteriorly (see Figures 14-18 and 14-20), the interdental septum between the second premolar socket and the alveolus of the mesial root of the first molar is twice as thick as that found between the first and second premo-lars. The socket of the first molar is divided by an interroot septum, which is strong and regular. The alveolus of the mesial root is kidney-shaped, much wider buccolingually than mesiodistally, and constricted in the center to accommodate developmental grooves found mesial and distal to the mesial root of the first molar. The alveolus of the distal root of the first molar is evenly oval with no constriction, conforming to the rounded shape of this root. The interdental septum between the alveoli of the mandibular first molar and the socket of the second molar is thick mesiodis-tally, although cancellous in character.

The mandibular second molar alveolus may be divided into two alveoli, as was the case in the first molar. However, often it is found to be one compartment near the periphery of the alveolus but divides into two compartments in the deeper portions. A septal spine occurs where the developmental grooves on the root are deep enough, or an interradicular septum will appear when the roots are entirely divided. The interdental septum between the second molar sockets and the third molar sockets is not as thick mesiodis-tally as the two interdental septa immediately anterior.

The mandibular third molar alveolus is usually irregular in outline (see Figure 14-21). Usually it is much narrower toward the distal than toward the mesial aspect of the alveolus. It may have interradicular septa or septal spines to accommodate itself to the irregularity of the root.

Figure 14-21 Alveoli of the first, second, and third molars. Features for special attention include the thin and perforated surface of the retromolar triangular space distal to the third molar alveolus and the cancellous formation in the alveoli proper and also in the interdental septa, which would allow a rich blood supply.

Figure 14-22 Illustration of the relative thickness of bone covering lingual mandibular second and third molar roots. A, Measurement of the thickness of bony cover lingual to the apex of the third mandibular molar immediately below the mylohyoid ridge. It measures only 0.5 mm. B, Repetition of measurement in the deepest portion lingually of the second molar alveolus. It measures fully 2 mm.

Figure 14-23 Comparison of the size and shape of mandibles at various ages. Top, Mandible of a 5-year-old. Notice the rounded bowlike form. Notice also the amount of space between the second deciduous molar and the ramus. Middle, Mandible of a 9-year-old. Notice the angular outline with constriction at the point of second permanent molar development. Bottom, Well-developed mandible of an individual approximately 50 years of age. The bone is regular in outline. The lingual constriction has lessened and has retreated to the third molar area.

Mesiodistal views of the teeth and their supporting structures can be made clinically using computed tomography to demonstrate the way that individual teeth relate to each other or to cortical and cancellous bone; however, vertical sections of a skull were made to illustrate these relation-ships1 shown in Figure 14-24. (See also Figures 13-29 and 13-30.)

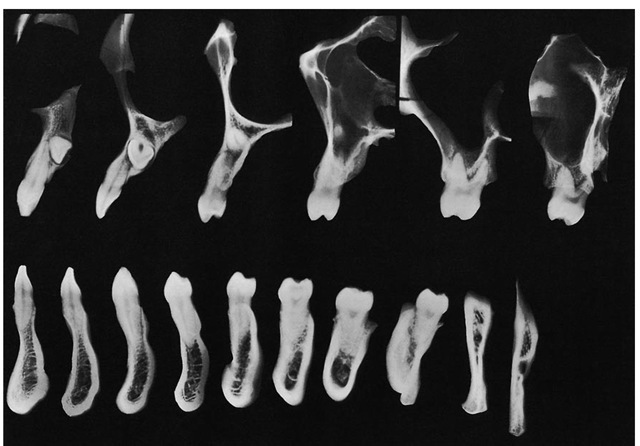

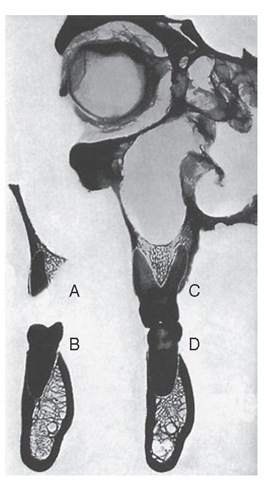

Some classical illustrations of sections of the axial relations of the maxillary and mandibular teeth are shown in Figures 14-25 through 14-32. These figures demonstrate the directional lines of the axes of the teeth and their alveoli (see also Box 16-1 and Figure 16-20). In addition, the radiographs of the sections graphically illustrate the relative densities of the teeth and supporting structures and show the outline and relative thickness of the bone over the various teeth at the site of each section.2

In Figures 14-25 through 14-32, note the axial relations of the superior and inferior teeth, the relative thickness of labial and lingual alveolar plates, the characteristics of the cancellous tissue, the relative densities, and the relation of the teeth to important structures. Compare the changes in the external contour and internal architecture of the adjacent sections. The sections in this series, with the exception of those in Figure 14-28, were taken from the same cadaver and are from the left side. A plaster cast was made before sectioning. The sections were reassembled in the cast and held in exact relation while being radiographed.

Figure 14-24 Some fine vertical sections of a skull made with radiographic problems in view. These radiographs of faciolingual sections show the extent of tooth attachment, the way in which individual teeth compare with each other, and the variances between cortical and cancellous bone in anchorage (see Figures 14-25 through 14-32). The maxillary canine was impacted in this specimen. Maxillary third molars were missing.

Figure 14-25 Central incisor regions, showing relation of superior central incisor to inferior lateral incisor.

Figure 14-26 Lateral incisor regions. Note position of apex of superior lateral incisor.

Figure 14-27 Canine regions. Note anterior extremity of maxillary antrum.

Figure 14-28 First premolar regions.

Figures 14-33, I and II illustrate the appearance of some of the bony landmarks of the maxilla and mandible as visualized in intraoral periapical radiography.3 Surfaces and dento-osseous structures are often important to recognize in relation to diagnostic and treatment aspects (Figure 14-34).

Figure 14-29 Second premolar regions.

Figure 14-30 First molar regions, showing relations of distobuccal root (A), distal half (B), and mesiobuccal (C) and lingual roots with mesial half of lower molar (D).