The development of the dentitions has been discussed and a brief review of the development of the neurocranium.Therefore, in this topic the focus is on the dentoalveolar and dento-osseous structures of the permanent dentition. The forms of the roots of the teeth and their sizes and angula-tions govern the shape of the alveoli in the jawbones, and this in turn shapes the contour of the dento-osseous portions facially.

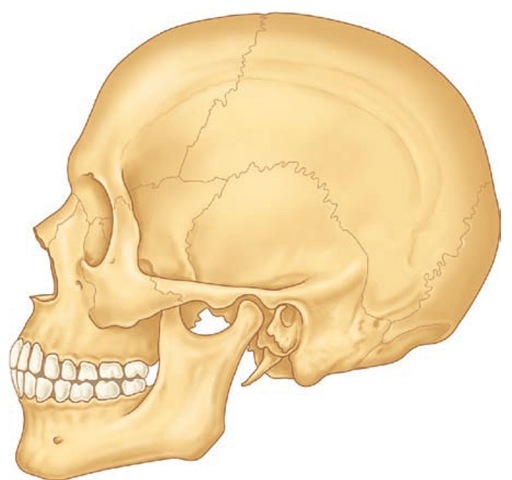

The osseous structures that support the teeth are the maxilla and the mandible. The maxilla, or upper jaw, consists of two bones: a right maxilla and a left maxilla sutured together at the median line. Both maxillae in turn are joined to other bones of the head (Figure 14-1). The mandible, or lower jaw, has no osseous union with the skull and is a movable (ginglymoarthrodial) joint.

The Maxillae

The maxillae make up a large part of the bony framework of the facial portion of the skull. They form the major portion of the roof of the mouth, or hard palate, and assist in the formation of the floor of the orbit and the sides and base of the nasal cavity. They support the 16 permanent maxillary teeth.

Each maxilla is an irregular bone, somewhat cuboidal in shape, which consists of a body and four processes: the zygomatic, frontal, palatine, and alveolar processes. The maxilla is hollow and contains the maxillary sinus air space, also called the antrum of Highmore. From the dental viewpoint, in addition to its general shape and the processes mentioned, several landmarks on this bone are among the most important, including the incisive fossa, canine fossa, canine eminence, infraorbital foramen, posterior alveolar foramina, maxillary tuberosity, pterygopalatine fossa, and incisive canal.

The body of the maxilla has the following four surfaces: anterior or facial, infratemporal, orbital, and nasal.

ANTERIOR SURFACE

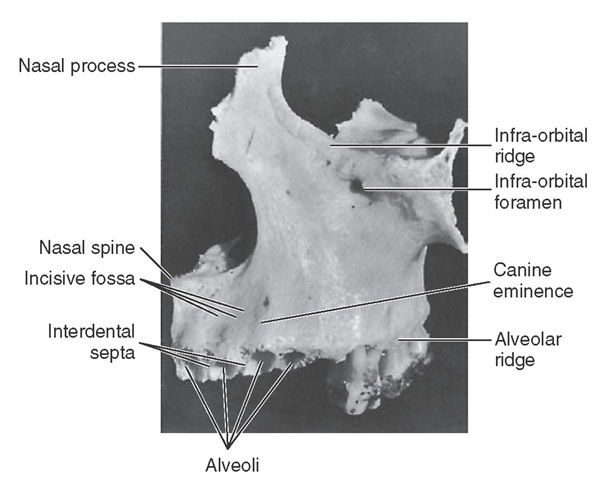

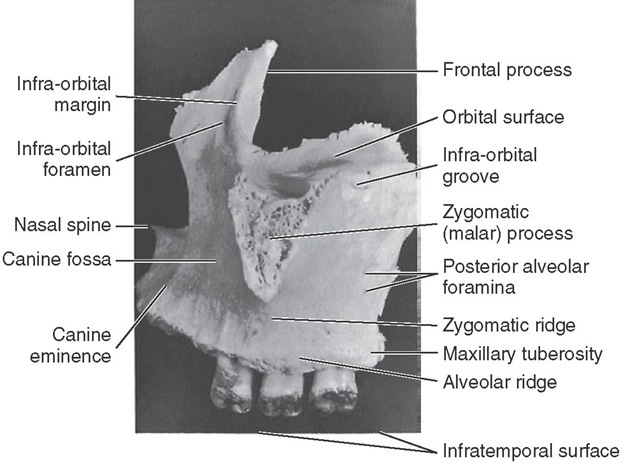

The anterior or facial surface (Figures 14-2 and 14-3) is separated above from the orbital aspect by the infraorbital ridge. Medially it is limited by the margin of the nasal notch, and posteriorly, it is separated from the posterior surface by the anterior border of the zygomatic process, which has a confluent ridge directly over the roots of the first molar. The ridge corresponding to the root of the canine tooth is usually the most pronounced and is called the canine eminence.

Anterior to the canine eminence, overlying the roots of the incisor teeth, is a shallow concavity known as the incisive fossa. Posterior to the canine eminence on a higher level is a deeper concavity called the canine fossa. The floor of this canine fossa is formed in part by the projecting zygomatic process. Above this fossa and below the infraorbital ridge is the infraorbital foramen, the external opening of the infraorbital canal. The major portion of the canine fossa is directly above the roots of the premolars.

FIGURE 14-1 Representation of an adult skull with permanent dentition. The maxilla consists of a body and four processes (malar, nasal, alveolar, and palatine) that articulate by synarthrosis with cranial and other facial bones, (e.g., frontal, nasal, ethmoid, malar bones). The mandible articulates with the temporal bone by the temporomandibular joint (see Figure 15-6).

FIGURE 14-2 Frontal view of left maxilla.

POSTERIOR SURFACE

The posterior or infratemporal surface (Figures 14-3 and 14-4) is bounded above by the posterior edge of the orbital surface. Inferiorly and anteriorly, it is separated from the anterior surface by the zygomatic process and the zygomatic ridge, which runs from the inferior border of the zygomatic process to the alveolus of the maxillary first molar. This surface is more or less convex and is pierced in a downward direction by two or more posterior alveolar foramina. These two canals are on a level with the lower border of the zygo-matic process and are somewhat distal to the roots of the third molar.

FIGURE 14-3 Lateral view of left maxilla.

The inferior portion of this surface is more prominent where it overhangs the root of the third molar and is called the maxillary tuberosity. Medially, this tuberosity is limited by a sharp, irregular margin that articulates with the pyramidal process of the palatine bone and, in some cases, the lateral pterygoid plate of the sphenoid bone. The maxillary tuberosity is the origin for some fibers of the medial ptery-goid muscle.

A portion of the infratemporal surface superior to the maxillary tuberosity is the anterior boundary to the ptery-gomaxillary fissure.

ORBITAL SURFACE

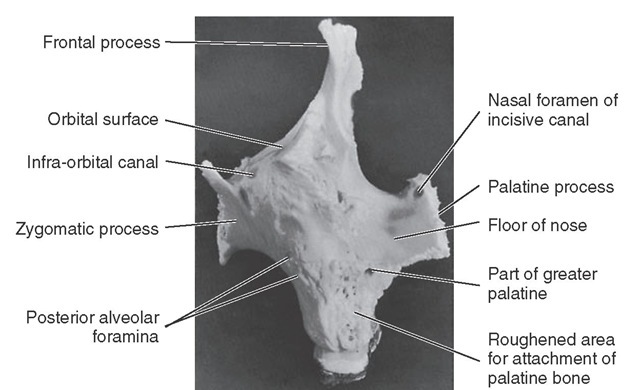

The orbital surface is smooth and together with the orbital surface of the zygomatic bone forms the floor of the orbit. The junction of this surface and the anterior surface forms the infraorbital margin or ridge, which runs superiorly to form part of the nasal process. Its posterior border or edge coincides with the inferior boundary of the inferior orbital fissure.

The thin medial edge of the orbital surface is notched anteriorly, forming the lacrimal groove. Behind this groove, it articulates for a short distance with the lacrimal bone, then for a greater length with a thin portion of the ethmoid bone, and terminates posteriorly in a surface that articulates with the orbital process of the palatal bone. Its lateral area is continuous with the base of the zygomatic process (see Figure 14-3).

Traversing the posterior portion of the orbital surface is the infraorbital groove. This groove begins at the center of the posterior surface and runs anteriorly. The anterior portion of this groove is covered, becoming the infraorbital canal, the anterior opening of which is located directly below the infraorbital ridge on the anterior surface.

If the covered portion of this canal were to be laid open, the orifices of the middle and anterior superior alveolar canal would be seen transmitting the corresponding vessels and nerves to the premolars, canines, and incisor teeth.

Figure 14-4 Posterior view of left maxilla.

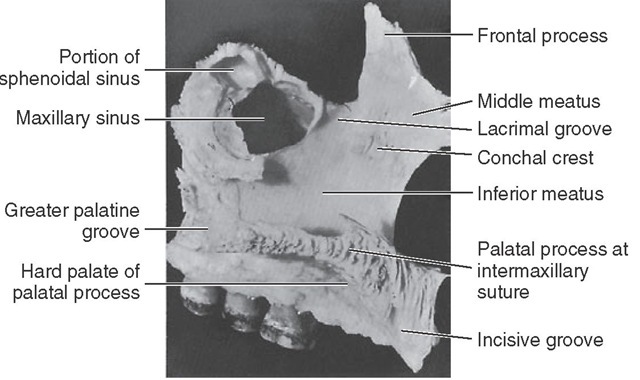

Figure 14-5 Medial view of left maxilla.

Figure 14-6 Medial view of right maxilla. This specimen has not been disarticulated completely and has the maxillary teeth in situ.

NASAL SURFACE

The nasal surface (Figures 14-5 and 14-6) is directed medially toward the nasal cavity. It is bordered below by the superior surface of the palatine process. Anteriorly, it is limited by the sharp edge of the nasal notch. Above and anteriorly, it is continuous with the medial surface of the frontal process. Behind this, it is deeply channeled by the lacrimal groove, which is converted into a canal by articulation with the lacrimal and inferior turbinate bones.

Behind this groove the upper edge of the nasal surface corresponds to the medial margin of the orbital surface, and the maxilla articulates in this region with the lacrimal bone, a thin portion of the ethmoid bone, and the orbital process of the palatine bone.

The posterior border of the maxilla, which articulates with the palatine bone, is traversed obliquely from above downward and slightly medially by a groove, which, by articulation with the palate bone, is converted into the greater palatine canal. Toward the posterior and upper part of this nasal surface, a large, irregular opening into the maxillary sinus (antrum of Highmore) may be seen. In an articulated skull, this opening is partially covered by the uncinate process of the ethmoid bone and the inferior nasal concha.

Anterior to the lacrimal groove, the nasal surface is ridged for the attachment of the inferior nasal concha. Below this the bone forms a lateral wall of the inferior nasal meatus. Above the ridge for a small distance on the medial side of the nasal process, the smooth lateral wall of the middle meatus appears.

ZYGOMATIC PROCESS

The zygomatic process may be seen in the lateral views of the maxillary bone as a roughly triangular eminence whose apex is placed inferiorly directly over the first molar roots. The lateral border is rough and spongelike in appearance, where it has been disarticulated from the zygomatic or cheek bone (see Figures 14-1 and 14-3).

FRONTAL PROCESS

The frontal process (see Figures 14-2 through 14-5) arises from the upper and anterior body of the maxilla. Part of this process is formed by the upward continuation of the infraorbital margin medially. Its edge articulates with the nasal bone. Superiorly, the process articulates with the frontal bone. The medial surface of the frontal process forms part of the lateral wall of the nasal cavity. Anteriorly, the frontal process articulates with the nasal bone.