The case study risk assessment process through the lens of the preceding disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation strategy discussion produced several critical observations particularly important for understanding the challenges and opportunities for cities facing climate change. These include the following:

First, a multidimensional approach to risk assessment is a prerequisite to effective urban development programs that incorporate climate change responses. At present most climate risk assessment is dominated by an overemphasis on hazards. The application of the climate risk framework developed in this topic provides more nuanced and more actionable insights into the differential risks. These insights reflect the exposure to hazards and the spectrum of vulnerabilities faced by urban households, neighborhoods, and firms. However, a critical issue that requires further research is identifying when strategic retreat may be more cost effective than adaptation and under what socio-economic conditions is it desirable and feasible.

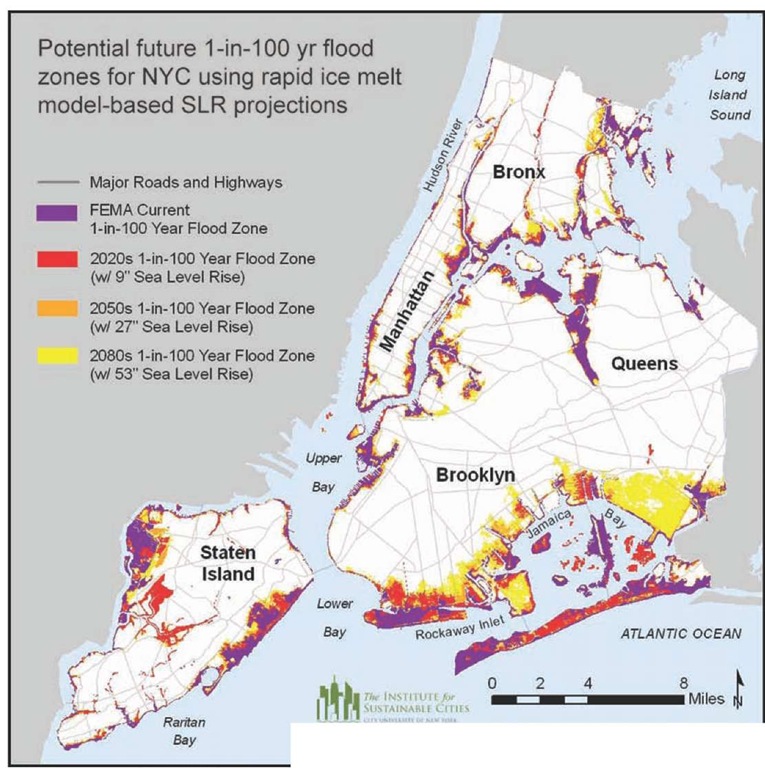

Note. This map is subject to limitations in accuracy as a result of the quantitative models, datasets. and methodology used in its development. The map and data should not be used to assess actual coastal hazards, insurance requirements or property values or be used in lieu of Flood Insurance Rate Maps issued by FEMA.

Interpretation. The floodplains delineated above in no way represent precise flood boundaries but rather Illustrate three distinct areas of interest: 1) areas currently subject to the 1-in-100 year flood that will continue to be subject to flooding in the future, 2) areas that do not currently flood but are expected to potentially experience the 1-in-100 year flood in the future, and 3) areas that do not currently flood and are unlikely to do so in the timeline of the climate projection scenarios used in this research (end of the current century).

Figure 2.22: Sea level rise projections.

Second, mismatches between needs and responses are occurring in regard to who should mitigate, how much to adapt, and why. Cities need climate change risk assessment, in addition to analysis of mitigation options, in order to decide for themselves what is the appropriate balance of mitigation and adaptation. Climate change risk frameworks, such as those described in this topic, can help cities to address the issue of mismatches; that is, the difference between the city’s response to climate change as opposed to the actual needs. For example, it appears that some developing countries may be over-focusing on mitigation when they could be addressing adaptation more due to the presence of critical climate risks in the near-term as well as in future decades. The 17 largest economies account for most of the greenhouse gas emissions, the root cause of climate change (US Department of State, 2009). And while many cities within these major economies have a significant role in mitigation, it may be prudent for cities in low-income countries with large populations of poor households to incorporate climate risk into ongoing and planned investments as a first step.However, since cities play an important role in greenhouse gas emissions in both developed and developing countries, there is also motivation for cities to lead on mitigation activities as well. Emissions from cities everywhere burden the environment, which is a global public good, and thus can be regulated through a combination of market and non-market incentives at the urban scale.

Third, the vertically and horizontally fragmented structure of urban governance is as much an opportunity as an obstacle to introducing responses to climate change. While much has been researched about the need for an integrated and coordinated approach, the fragmented governance structure of cities is unlikely to change in the short term and offers the opportunity to have multiple agents of change. Examples in the case study cities show that early adopters on climate change solutions play an important role. As in the case of New York City, the city’s early action has become a model for other cities within the USA and internationally. The broad spectrum of governmental, civil society, and private sector actors in cities encourages a broader ownership of climate change adaptation programs.

Further, gaps and future research for scaled-down regional and local climate models were identified. In addition to the difficulties global climate models have with simulating the climate at regional scales, especially for locations with distinct elevational or land-sea contrasts, they also continue to have difficulty simulating monsoonal climates. Such is the case for climate projections for some of the case study cities in this topic, especially related to projected changes in precipitation. This is because simulation of seasonal periods of precipitation is challenging in terms of both timing and amount; in some cases the baseline values used for the projection of future changes are extreme – either too high or too low. Therefore, the percentage changes calculated vary greatly and can, on occasions, have distorted values. Especially for precipitation projections, the future trends may appear to be inconsistent when compared to observed data, because the averages from the baseline period to which the projected changes were added are inaccurate, either due to a lack of data or extreme values within the time period that are skewing the averages. The inability of the global models to simulate the climate of individual cities raises the need for further research on regional climate modeling.

However, what is important to focus on in these future climate projections is the general trends of the projected changes and their ranges of uncertainty. These refer to attributes such as increasing, decreasing, or stable trends, and information about the uncertainty of projections in particular due to climate sensitivity or greenhouse gas emission pathways through time. Information on climate model projections regarding the extreme values and the central ranges both provide useful information to city decision-makers.

Global institutional structure for risk assessment and adaptation planning2)

Moving forward, there is a need for a programmatic science-based approach to addressing climate risk in cities of developing countries that are home to a billion slum dwellers, and quickly growing. These cities are most unprepared to tackle climate change-induced stresses that are likely to exacerbate the existing lack of basic urban services such as water supply, energy, security, health, and education, as well as of disaster preparedness and response. Most climate change adaptation efforts until now have focused on lengthy descriptive papers or small experimental projects, each valuable in their own right, but insufficient to inform policymakers. Further, there is little recognition of the need for a flexible strategy to adaptation; instead there are sporadic medium- and long-term project-oriented responses, often lacking analysis of basic climate parameters such as temperature variability, precipitation shifts, and sea level rise data. Three central elements of a comprehensive approach could include:

1. Establishment of a scientific body, which can verify as well as advise on technical matters of climate change science as it pertains to mitigation and impacts on cities;

2. A systematic approach to climate change adaptation;

3. Ongoing assessment of climate change knowledge for cities.

The most pressing needs for developing-country cities in low-income countries is to focus on adaptation, outlined here, but similar measures are essential for mitigation efforts as well.

For adaptation, there is a requirement for assessing risk, evaluating response options, making some politically complex decisions on implementation choices and implementing projects, monitoring process and outcomes, and continuously reassessing for improvements as the science and practice evolve. Further, in order to maximize impact, there is a need to leverage ongoing and planned capital investments to reduce climate-risk exposure, rather than to neglect potential climate impacts. Practitioners and scholars agree that a primary reason why cities neglect climate change risks is lack of city-specific relevant and accessible scientific assessments. Thus, to reduce climate risk in developing-country cities there is a demand for city-specific climate risk assessment as well as the crafting of flexible adaptation and mitigation strategies to leverage existing and planned public investments.

To inform action, the experience of the Climate Impacts Group at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies and scholars at Columbia University and the City University of New York points to a need for at least a four-track approach.

Track 1: Addressing the need for a global progress assessment. This is an across-city global assessment that captures the state-of-knowledge on climate and cities. The First UCCRN Assessment Report on Climate Change and Cities (ARC3) is one of the only ongoing efforts that addresses risk, adaptation, and mitigation, and derives policy implications for the key city sectors – urban climate risks, health, water and sanitation, energy, transportation, land use, and governance. This assessment is an effort by more than 50 scholars located all over the world and offers sector-specific recommendations for cities to inform action. The aim is to continue assessments (on the order of every four years) and offer Technical Support after the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change COP16 has been held in December, 2010 in Mexico City.

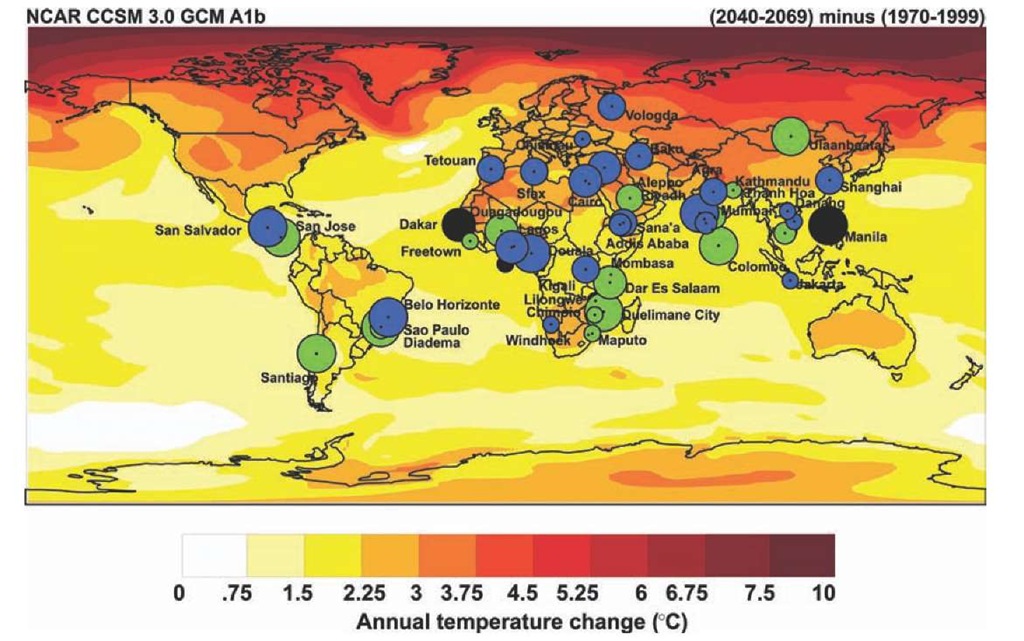

Figure 2.23: Cities involved in Cities Alliance activities, 2008, and temperature projections for the 2050s. Green circles represent national slum upgrading plans: blue, city development strategies; and black, both.

Track 2: Across-city rapid risk assessment. Mainstreaming climate risk assessment into City Development Strategies as well as pro-poor programs like Cities Alliance’s citywide and nationwide slum upgrading. This effort is critical to inform ongoing large-scale capital investments in cities that often lack basic climate risk considerations (see Figure 2.23). For most cities illustrated in Figure 2.23, between 50 and 100 years of observed climate data are available but remain to be analyzed.

Track 3: City-specific in-depth sectoral assessment. General assessments are insufficient as many cities lack in-house expertise for technical analysis of city-specific climate impacts. To fill this gap, there is a requirement to craft city-specific risk and adaptation assessments for city departments (sector by sector) to redirect existing and planned investments. Cities like New York, London, and Mexico City have initiated this demanding, yet essential task. Such risk analysis needs to disaggregate risk into hazards (external climate-induced forcing), vulnerability (city-specific characteristics, such as location, and percentage of slum population), and agency (ability and willingness of the city to respond). The process will engage in-city experts and stakeholders in each city in the assessment process in order to develop local adaptive capacity.

Track 4: Learning from experience. This task involves deriving adaptation lessons from the early climate change adopters like London, Mexico City, and New York City.

Table 2.6: Four tracks with objectives, and related outputs.

|

Track |

Objective |

Output |

|

1. Global progress assessment |

To provide state-of-knowledge |

Providing a global First UCCRN Assessment Report on Climate Change and Cities (ARC3), a comprehensive assessment of risks, adaptation, mitigation options, and policy implications |

|

2. Across-city rapid risk assessment |

To inform ongoing urban investments that lack climate risk considerations |

Integrate climate risk assessment into City Development Strategies and pro-poor programs |

|

3. City-specific in-depth sectoral assessment |

To redirect existing and planned investments |

Crafting city-specific risk and adaptation assessments for each city department (sector by sector) |

|

4. Learning from experience |

To derive adaptation lessons from the early adopters |

Detailed case-studies of implementation mechanisms from London, Mexico City, New York City, etc. |

It focuses on answering such questions as: How are London, Mexico City, and New York crafting a response to climate change? What are the institutional arrangements? What are the roles of mayoral leadership, public demand, offices of long-term planning, and civil society initiatives? How are assessments financed – for example foundations, scientist-volunteered, tax dollars? What are the positive externalities – such as establishment of the C40 Large Cities Climate Summit – of scaling-up both nationally and internationally? And what are transferable lessons? What can other cities learn from these experiences? Table 2.6 summarizes the four tracks along with their objectives and related outputs.