Complications

In-hospital death, the most significant complication of ASA, is rare. Nevertheless, it ranges in the literature from 1 to 4%. However, some observations suggest that in skilled hands, the mortality rate is close to zero.

Historically, the incidence of complete heart block following ASA has ranged from 0 to 40% with a mean value of 8 to 18%.However, the original technique of ASA has undergone several modifications and lower occurrence of post-procedural complete heart block has been reported.The most important trend in the continuously developing ASA technique involves the lowering of the alcohol dose (1 to 2 ml) injected in very small fractions (0.1 to 0.3 ml).Subsequent small infarctions are sufficient in reducing obstruction to a similar extent as larger infarctions induced by a higher dose of alcohol. Moreover, it seems to be likely that a low dose of alcohol is associated with lower incidence of major post-procedural conduction disturbances and improved prognosis (Kuhn, 2008).

The selection of appropriate patients for this procedure appears to be as important as the procedural ASA technique itself. Only highly symptomatic patients without the left bundle branch block should be treated by ASA because of high incidence of right bundle branch block following ASA. Unfortunately, the resulting complete heart block can occur with no previous symptoms within hours or days after the procedure. Therefore, based on our clinical experience, patients after uncomplicated ASA should be observed in the coronary care unit for at least 2 or 3 days and consequent telemetric monitoring should be considered for at least 1 week.

To improve the risk stratification of complete heart block occurrence, Faber et al. proposed a scoring system based on baseline ECG, heart rate profile, severity of obstruction, peri-interventional enzyme kinetics, and peri-interventional conduction problems that might discriminate patients with a high risk for permanent pacemaker dependency from those with a stable atrioventricular conduction after ASA (Faber, 2007).

Sustained ventricular tachycardia has been rarely reported following ASA and only few reports have described it as an early post-procedural complication.There is the hypothesis that the early post-procedural period can be compared to the same period after acute myocardial infarction, and the development of sustained ventricular arrhythmias after the ASA is not as rare as was thought before. It seems to be likely that a lower dose of alcohol with the minimising of the resulting necrosis (scar) is unable to entirely eliminate either occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias that are dependent on disorganised cellular architecture of myocardium or serious conduction abnormalities.

Still, some uncertainty persists regarding the ICD indication for the prevention of sudden death in patients with post-procedural sustained ventricular arrhythmias, and no data are available regarding their predictive power. Nevertheless, based on both our clinical experience (and lack of scientific evidence), we do not consider early post-procedural ventricular arrhythmias to be a sufficient justification per se for an ICD implantation. A serious complication of ASA is a leakage of ethanol from the target septal branch into the left anterior descending artery. This potentially fatal complication is avoided by the use of a slightly over-sized angioplasty balloon catheter and a very careful septal branch angiography that precedes alcohol ablation. Additionally, the slow administration of alcohol per fractions and septal branch occlusion for 5 minutes after the last alcohol injection ensure the safe course of the procedure.

Theoretically, the potential risk of ventricular septal rupture following ASA should be considered. Surprisingly, this serious complication is probably very rare, although it is possible that it is underreported in the literature.

Results

ASA has not been subjected to many randomised clinical trials. However, observational data from European and US centres over a 16-year follow-up are consistent, attributing a number of favourable effects to ASA that generally parallel that of surgery, including gradual and progressive reduction in outflow gradient over 3 to 12 months and alleviation of symptoms. The most important finding after ASA is an impressive symptomatic improvement during both short- and long-term follow-up that is consistently reported by all groups dealing with ASA. The mean functional class improved very significantly from NYHA 2.5-3 to 1.2-1.6. Similarly, objective measurements showed an increase in exercise capacity and peak oxygen consumption.

During ASA, an acute LVOT gradient reduction is followed by a significant LVOT gradient increase during the early post-procedural period and a continuous LVOT gradient decrease during the follow-up. The rapid post-procedural LVOT gradient decrease is probably associated mainly with stunning, myocardial necrosis and the change in the left ventricular ejection dynamics. The later pressure gradient decrease is caused by scarring and thinning of the basal septum, resulting in left ventricular remodelling.

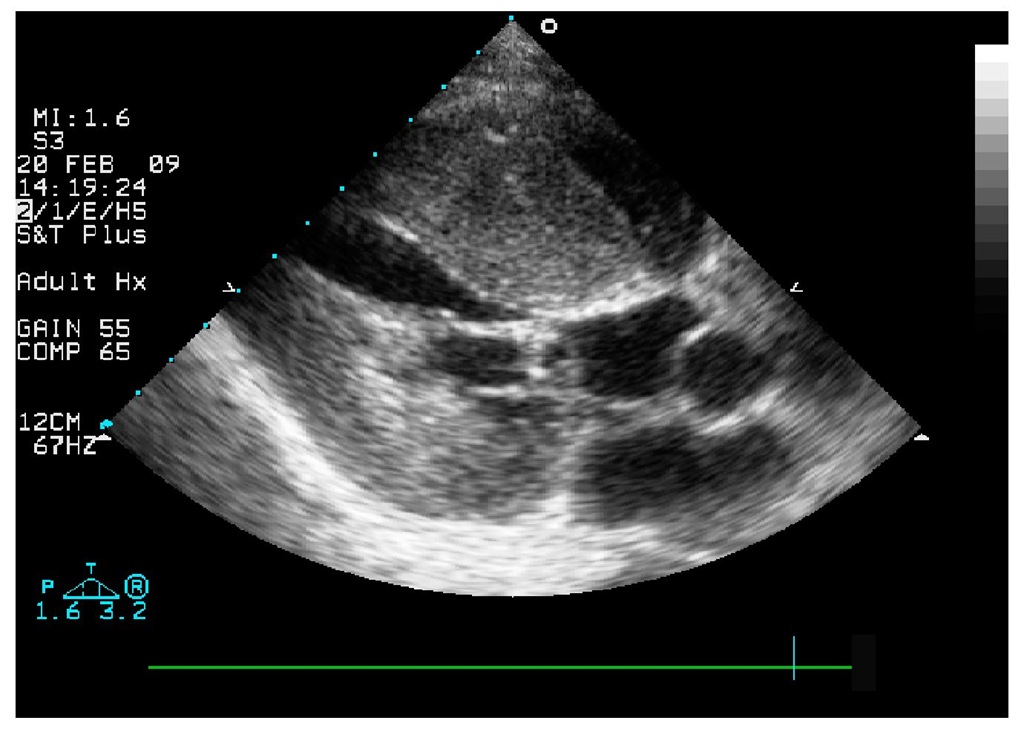

Fig. 6. Transthoracic echocardiography, parasternal long axis view with impressive finding of subaortic obstruction.

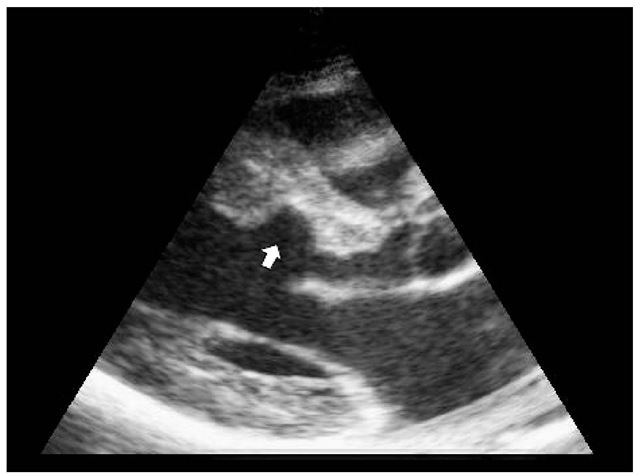

Fig. 7. Transthoracic echocardiography, parasternal long axis view with thinning of the basal interventricular septum (arrow) three months following ASA.

This haemodynamic course characterised by "down-up-down" changes in pressure gradient occurs in the majority of patients and is called the "biphasic" response. In most trials, the resting LVOT pressure gradient is reduced from 60 to 70 mmHg at baseline to 10 to 20 mmHg at mid- or long-term follow-up.

Conclusion

At present, there is not a single therapy that should be applied to all patients with severely symptomatic HOCM unresponsive to medical management. There are benefits and disadvantages of both surgical myectomy and ASA. Septal myectomy requires specialised tertiary referral centres and is a more complex procedure than ASA. Furthermore, there is no cardio-thoracic surgical centre in our country that would be able to perform this procedure routinely. On the other hand, there are no sufficient data concerning the long-term follow-up of patients after ASA.

Further investigation is required to be able to identify the best responders for cardiac pacing, ASA and surgical myectomy and compare the results for the available methods. Mainly, a randomised study comparing myectomy and ASA would be needed. However, low incidence of end points would require extremely high number of participants and, therefore, such a study will probably not be performed.

Currently, a decision concerning the best therapy of patients with HOCM must be individualised to each patient depending on their wishes and expectations, way of life, age and haemodynamics. Centres of excellence are able to perform both ASA and myectomy very safely and effectively. Therefore, choice of the final therapy should be tailored for the individual patient treated in a particular centre.