TRENDS IN CANCER DISPARITIES

Tracking and monitoring temporal trends in cancer disparities are crucial for evaluating efforts to reduce these disparities. However, the interpretation of how disparities have changed over time depends on whether absolute or relative differences are measured. For example, if mortality rates among two groups decrease annually by the same absolute value, the absolute disparity (the arithmetic difference in the rates) remains constant over time, but the relative disparity (the rate ratio) increases continuously. To fully monitor health disparities, the general consensus is that both relative and absolute measures are required. However, from the public health point of view, absolute change in disparities should be emphasized because it reflects the magnitude of disparities in the population and is more relevant to decision making about resource allocation for cancer disparity reduction (Harper & Lynch, 2005).

Trends in Racial/Ethnic Disparities

Figure 2.4 depicts the age-standardized sex- and race-specific incidence and death rates for all cancers combined between 1975 and 2007 (Altekruse et al., 2010). Among men, the Black-White disparity in incidence and death rates for all cancers combined widened from 1975 until the early 1990s, and then continuously narrowed up to 2007. Among women, overall cancer incidence rates have remained similar, and the gap in mortality rates between the two races has remained relatively stable over time; Black women continue to experience higher cancer mortality rates than White women, despite lower incidence rates. However, the temporal pattern of disparities in overall cancer incidence and mortality rates masks changes in racial disparities for specific cancer sites.

FIGURE 2.4 Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates for African Americans and Whites for All Cancers Combined in the United States, 1975-2007

Age adjusted to the 2000 US standard population.

The Black-White disparities in lung cancer incidence and mortality have been narrowing since the early 1990s, due to more favorable downward trends in tobacco use by African American men in the last decades of the twentieth century (Figures 2.5 and 2.6) (Altekruse et al., 2010). Notably, the disparities in lung cancer death rates between Whites and Blacks under the age of 40 have been eliminated in both men and women (Figure 2.7) (Jemal, Center, & Ward, 2009).

FIGURE 2.5 Cancer Incidence Rates for African Americans and Whites for Lung, Colorectal, Female Breast, and Prostate Cancers in the United States, 1975-2007

Age adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population.

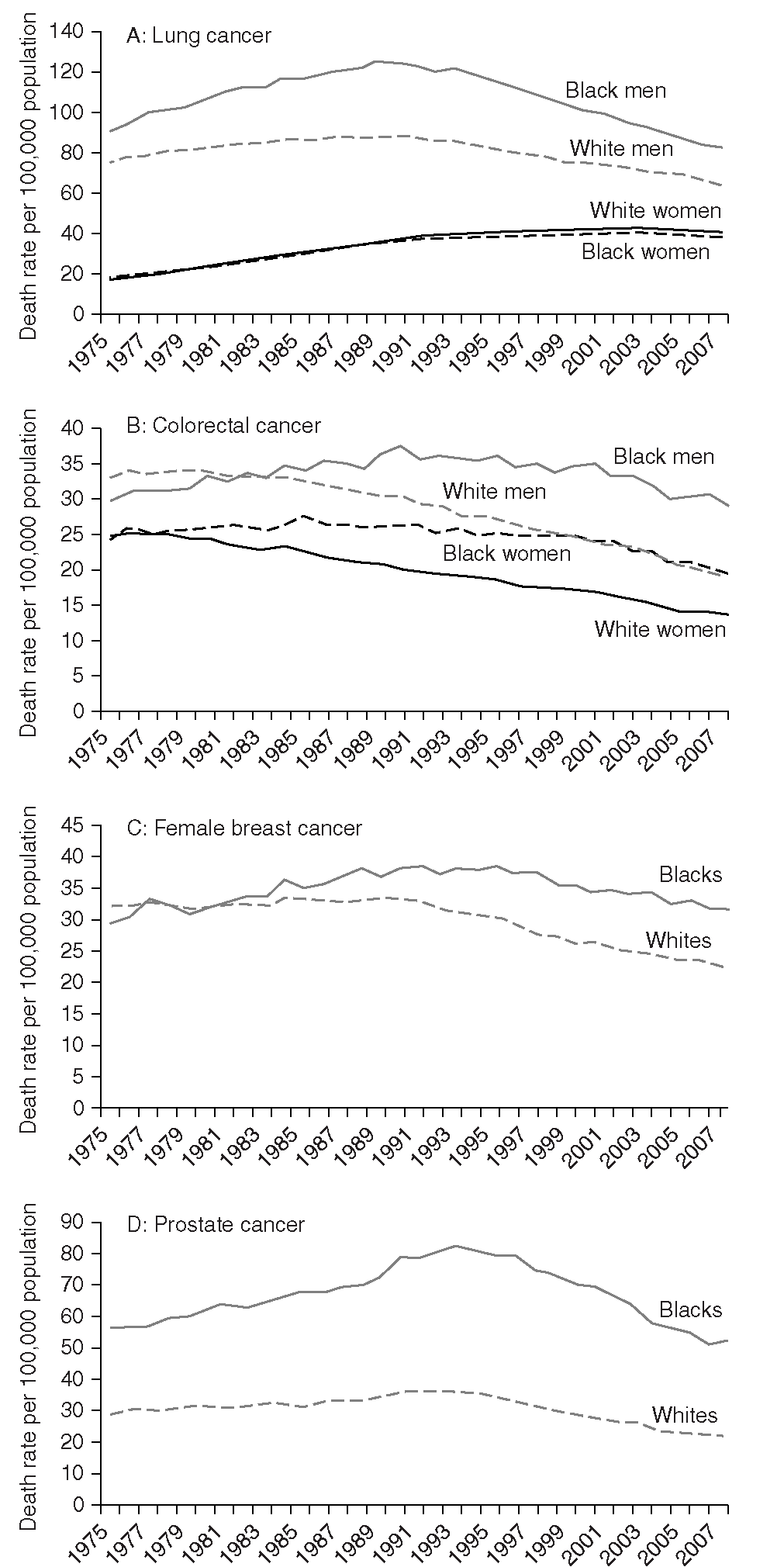

FIGURE 2.6 Cancer Mortality Rates for African American and Whites for Lung, Colorectal, Female Breast, and Prostate Cancers in the United States, 1975-2007

Age adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population.

FIGURE 2.7 Trends in Lung Cancer Death Rates by Race in Men and Women Aged 20-39 Years, 1992-2007

Dots represent observed data; lines represent fitted data.

The convergence of cancer rates in Blacks and Whites for smoking-related cancers (DeLancey, Thun, Jemal, & Ward, 2008) largely explains the recently narrowed racial gaps in overall cancer incidence and mortality. In contrast, for cancers that are affected by improved screening and/or treatment (female breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers), the Black-White disparities in mortality have been widening over the past three decades (Figures 2.5 and 2.6). This suggests that improvements in early detection and treatment have not equally reached all segments of the population; targeted programs directed at disadvantaged populations to improve access to early detection and treatment are essential to eliminate racial disparities in cancer mortality.

For stomach and liver cancer, minority populations (API, Hispanic, and AI/AN) continue to have disproportionately higher death rates than Whites, although these disparities have been narrowing in recent years for some minority groups (Edwards et al., 2010). For example, between 1997 and 2006, the liver cancer death rate annually increased by an average of 2.2% in White men, whereas the rate increased 1.3% in Hispanic men and decreased 1.3% in API men. For stomach cancer, although the death rates were falling in all racial/ethnic groups between 1997 and 2006, a quicker drop occurred in the API population than in Whites.

Trends in Socioeconomic Disparities

Data on trends in socioeconomic disparities in cancer incidence and mortality are limited in the United States. Using area-level poverty as an indicator of SES, Singh et al. (2003) did not observe consistent socioeconomic gradients in cancer incidence over time. Kinsey et al. (2008) examined the trend in mortality for the major cancer sites between 1993 and 2001 among working-aged (25-64 years) populations and found that the recent declines in death rates from major cancers in the United States mainly reflect declines in more-educated individuals, regardless of race. Except for lung cancer in Black women, death rates for the four major cancers decreased significantly from 1993 to 2001 in persons with at least 16 years of education among Blacks and Whites of both sexes. In contrast, among persons with less than 12 years of education, death rates decreased only for breast cancer in White women; death rates increased for lung cancer in White women and for colon cancer in Black men (Kinsey et al., 2008). These results indicate that socioeconomic disparities in cancer morality, at least through 2001, were widening, rather than narrowing, in working-age populations in the United States.

Using area-level poverty as an SES indicator, Singh et al. (2003) also reported widening area socioeconomic gradients in all-cancer mortality among U.S. men from 1975 to 1999, and reversed socioeconomic gradients in allcancer mortality over time among U.S. women; among men, the death rate for all cancers combined was 2% higher in poorer areas than in more affluent counties in 1975, but increased to 13% by 1999. Contrastingly, in women, all-cancer mortality was 3% lower in poorer areas compared with more affluent counties in 1975, but in 1999, the rate was 3% higher in poorer areas. Mortality trends for the specific cancer sites showed similar patterns over time, with widening area socioeconomic disparities observed for male lung and prostate cancers and a reversal in the disparities for female colorectal and breast cancer mortality rates.

CONCLUSION

African Americans continue to bear a disproportionally greater cancer burden than Whites in the United States, largely due to differences in access to health services for cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment. While the Black-White disparities in mortality rates have narrowed for smoking-related cancers, in the most recent time period, they continued to increase for cancers affected by screening and/or treatment, including colorectal, female breast, and prostate cancers. It is also noteworthy that the disparities by socioeconomic status are larger than those by race. Therefore, more emphasis should be placed on improving access to screening and treatment among all disadvantaged segments of the population, in order to narrow or eliminate cancer disparities. In addition, primary prevention focusing on modifiable risk factors should be emphasized, as incidence continues to be higher in Blacks for most cancer sites and in other ethnic groups for infection-related cancers, such as liver, stomach, and cervical cancer. Importantly, effective i mplementation and evaluation of efforts to reduce disparities depend on timely collection and analysis of reliable surveillance data. This requires an improvement of the current data collection system, in which detailed and systematic data on race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, insurance status, and quality of care are still lacking. The goal of eliminating disparities can only be achieved by coordinated and sustained efforts on the part of governmental, academic, and private organizations, as well as individuals devoted to cancer prevention.