Eihei-ji

Eihei-ji is the lead temple of the Soto Zen community in Japan. It was founded in 1243 by Dogen (1200-53), who had earlier introduced Soto practice from China. As part of his activity to spread Zen, in 1243 Dogen published his book, SHOBOGENZO. In it he argued that Zen was a better form of Buddhism in terms of its essential national duty. Buddhism was seen as an essential national asset shielding the nation from a variety of evils including wars and natural disasters. The book created a firestorm in the larger Buddhist community with even the supporters of Rinzai Zen joining the attack.

Dogen concluded that withdrawal from the conflict was his best course, and at the end of the summer in 1243 he moved to Echizen Province (contemporary Fukui Province) and an estate owned by a staunch lay disciple, Hatano Yoshishige. He opened a temple and lived a secluded existence. This temple was renamed Eihei-ji, "Temple of Eternal Peace," in 1246, the new name referring to the period when Buddhism was initially transmitted to China from India. Dogen emphasized the monastic ideal. After Dogen’s death, his primary disciple, Koun Ejo (1198-1280), became the abbot. He was succeeded by Tetsu Gikai, then Gien (d. 1314), and Giun (1253-1333).

Eihei-ji grew into a large monastic complex over the years, its remote location serving it well. In the 20th century, it began to welcome Western Zen practitioners, and from its facilities Soto Zen has spread to the West. Every 50 years a memorial service for Dogen is held, most recently in 2002.

Eisai (Yosai)

(1141-1215) Japanese Rinzai Zen master who was first transmitter of Zen to Japan

Eisai was a Buddhist priest who visited China in 1168 and 1187 c.e. During his second visit, he received the "seal" (inkashomei) of Zen transmission from Xuan Huaichang. Eisai then established the Shofuku-ji in Kyushu, the first Rinzai temple in Japan. He was later, in 1204, appointed abbot of the Kennin-ji monastery in Kyoto. It was here that Eisai was the first master of Dogen, who went on to transmit SoTo Zen to Japan. Finally, he established the Jufuku-ji in Kamakura.

As most monks of his time did, Eisai studied Tendai and Shingon at Mt. Hiei. However, after his discovery of Rinzai in China he became a critic of Tendai. Tendai monks in Japan were as a result quite antagonistic to Eisai; his school was banned for a while. However, he gained the support of the Kamakura era shogun Minamoto Yoriie, support that allowed him to teach in the centers of Kyoto and Kamakura.

Ironically Eisai’s own lineage, the Oryo lineage of Rinzai, died out a few generations after his death. His importance lay in his transmission of Rinzai teachings and, in his own writings, his new synthesis of Shingon, Tendai, and Zen elements. He is considered the first monk to have established Zen teachings in Japan.

Ekayano magga (Sanskrit: ekayana marga)

Literally "one path," the term ekayano magga (Pali: ekaayam) was used by the Buddha when describing the Four Foundations of Mindfulness in the Mahaasatipatthaana Sutta, a Pali work. In this sutra, the Buddha explains that there is only one way or path to achieve purification, only one method to overcome the pains and discomforts of life, only one way to achieve nirvana. The one path consists of practicing the Four Foundations of Mindfulness: dwelling in contemplation of the body, dwelling in contemplation of the feelings, dwelling in contemplation of the consciousness, and dwelling in contemplation of the dharmas. Essentially, only mindfulness can allow one to achieve nirvana.

The concept of "one way" indicates that the Buddha’s method is certain; there are no forks or deviations in the path. In addition, it is a method to be employed by each as an individual, as a "one," and not as a group. It can also be interpreted to mean the "Path of the One," referring to the Buddha himself as the one, a totally unique being.

Enchin (Chisho)

(814-891) founder of the Jimon sect of Tendai Buddhism

Enchin (Chisho), founder of the Jimon sect of Tendai Buddhism, was the nephew of Kukai, the founder of Japanese Shingon Buddhism, but instead of following his uncle’s teachings, Enchin affiliated with Tendai Buddhism. He traveled to China for six years (852-858) and upon his return to Japan opened a study center at the Miidera temple on Mt. Hiei, where Tendai was headquartered.

Miidera was soon directly affiliated with Enryaku-ji, the lead Tendai temple, over which Enchin became abbot in 868, shortly after the death of Ennin (794-864). Enchin would remain at Enryaku-ji for the rest of his life.

In 866, Enchin also became head of Onjo-ji, the traditional temple of the powerful otomo family, in Otsu City. For several decades after Enchin’s death, monks in the lineage of Enchin and/or Ennin would head Enrayaku-ji. In 933, however, a dispute over the leadership succession led to a schism and the faction who traced their lineage to Enchin left Enrayaku-ji and established themselves at the Onjo-jo Temple, which became the headquarters of the Jimon sect of Tendai Buddhism.

Engaged Buddhism

The idea of "engaged Buddhism" first emerged within the Zen Buddhist community in vietnam during the ongoing conflict that began with the defeat of French colonial powers and continued as the vietnam War in the 1960s. The vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh gave voice to a dilemma faced by his community. As the war began to affect their neighbors, they asked themselves how they should react. Their first reaction was to maintain their monastic organization emphasizing their inner cultivation and not react to the transitory events around them. However, the suffering of people called them to move out from the monasteries and begin to assist those suffering physically and psychologically from the bombs. They decided to go forth into the world out of the insight (mindfulness) they had obtained from their meditative practices.

As Thich Nhat Hanh put it in his book Peace Is Every Step, "Mindfulness must be engaged. Once there is seeing, there must be acting." Hanh’s new approach, while not altogether unique, has become a vital element in the emergent Buddhist community in the West. Hanh and his compatriots moved from simply assisting individuals who were hurrying to protest the war that caused their suffering to an analysis of the conditions of peace to the development of a way for Buddhists to be in the world and relate to the many socially upsetting phenomena they would have to encounter.

Through the mid-1960s, Hanh and his colleagues established a study center in Saigon, the An Quang Pagoda, and began to organize people to provide services for the population victimized by the war. In the process of opposing the war he began to adopt the nonviolence activism articulated by Mahatma Gandhi and the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. (the U.S. civil rights movement was then at its height).

There are two main centers from which the engaged Buddhist approach is disseminated. Hanh now lives at Plum Village, a monastic community in Loubes-Bernac, France. Here the Unified Buddhist Church is headquartered as well as the Order of Interbeing, the international association founded in 1968 for people committed to engaged Buddhism. Plum Village itself exists as a place where people involved in the work of social transformation can receive rest and spiritual nourishment while improving their skills for introducing mindfulness into everyday life. It welcomes thousands of visitors annually.

Community of Mindful Living (CML) was formed in 1983 to promote and support the practice of mindfulness for individuals, families, and societies inspired by Thich Nhat Hanh. It is now an official arm of the unified Buddhist Church and part of a collection of church agencies operating in and around Berkeley, California, including the church publishing arm, Parallax Press, and Deer Park Monastery.

Engaged Buddhist sanghas are now found around the world. The concept has been so successful that it is now applied to most instances in which Buddhist groups become involved in social causes. It no longer refers solely to Thich Nhat Hanh’s groups or his teachings.

Enlightenment (bodhi, satori)

Enlightenment is the common English translation for the Sanskrit term bodhi. However, the English word enlightenment enjoyed a long history before Buddhism was introduced to the West and carried certain connotations, such as introducing light and clarity to one’s vision of the world. With the discovery of the Buddhist tradition by scholars in the West in the late 19th century, the term was applied to what was seen to be the goal of Buddhist practice. However, the Sanskrit root budh actually means "awaken." Rather than a brighter, better-lit view of a familiar reality, BODHI is an awakening, an awareness of the true nature of reality as if seeing it for the first time.

One Pali commentary (the Vibhangat-thakatha) describes this by saying that the enlightened person will "emerge from the sleep of the stream of defilements." This emergence is characterized by complete understanding of the Four Noble Truths or a direct realization of nirvana. In general the Pali scriptures and commentaries see bodhi as a kind of knowledge, part of wisdom. Awakening experience, the activation of knowledge of reality, brings about a change in the quality of the dharmas (components of reality) that, when arising, constitute the individual. The entity that experiences this knowledge is defined simply as a collection of skandhas or aggregates; the individual does not in any ultimate sense exist as a separate entity. The awakened person becomes a noble person, a bhodin, or awakened one.

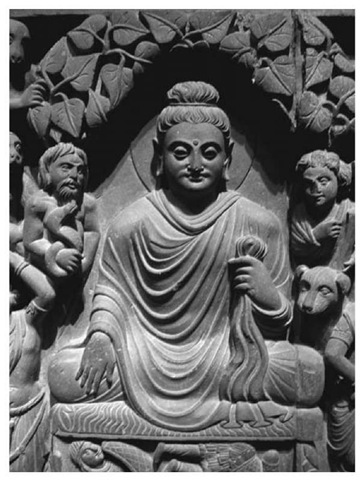

Stone image of the Buddha informing the universe of his enlightenment by touching the earth (bhumisparsa mudra); from a carved relief depicting the life of the Buddha, second to third century C.E.; originally from Gandhara, Central Asia, now in the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Museum, Washington, D.C.

The first enlightened one to share with others the experience of bodhi was the Buddha—the "awakened one." The Buddha was a man who through self-effort attained a certain understanding and perception of reality. While sitting under the Bodhi tree, he saw through everyday perceptions to the underlying nature of the universe. In Mahayana terms that nature is SUNYATA, emptiness. He also saw that this emptiness was not separate from the world of perceptions. It is a profound vision of unity, without dualities.

After the Buddha’s death Buddhist practitioners developed techniques of religious cultivation to help a practitioner attain enlightenment. In classic Buddhist theory these consist of 37 practices—called bodhipaksikiadharma— categorized into seven groups. The 37 practices entail more than simple techniques of meditation, and it is important to note that Buddhist practice extends to issues of moral reflection as well as consciousness.

The first group includes the four fields of mindfulness: contemplating the body (and its impure nature), contemplating feeling to register suffering, contemplating mind to see imperma-nence, and contemplating phenomena to be able to notice that phenomena do not contain self.

The second group, the four right efforts (catvari samyakprahanani), are to eradicate evil already present, to prevent evil not yet arisen, to help good to arise, and to improve the good already present. Kogen Mizuno, a contemporary writer, cautions that evil here means simply that which leads away from an ideal, while good is its opposite.

The third group is the set of four psychic powers, which all relate to Dhyana, or a state of meditation: the will to obtain Dhyana, the effort to obtain Dhyana, the mind to attain Dhyana, and the research into wisdom to attain Dhyana.

The fourth group is the five roots of freedom that lead to good conduct: faith, endeavor, mind-fulness, concentration, and wisdom.

In the fifth group are five "excellent" powers (panca balani), which correspond to the five roots listed in the fourth group. They are simply the roots as practiced by an experienced cultivator, at an advanced level.

In the sixth group are seven factors of enlightenment, on which the cultivator should focus just prior to reaching enlightenment. These help the cultivator obtain liberation and supernatural knowledge. They are mindfulness; investigation of the Dharma, the Buddha’s doctrines; endeavor;joy; tranquility; concentration; and equanimity— seeing all mental phenomena with dispassion.

The final, seventh group of the 37 consists of the Eightfold Path as originally taught by the Buddha—right view, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right mindfulness.

As a result of the complexity and variety of practices that developed later, the 37 practices were often summarized by reference to the three overall Buddhist practices of sila, samadhi, and prajna, a formula that continues to be a succinct description of Buddhist cultivation.

The 37 practices are described in detail by two great Abhidharma masters, Buddhaghosa, who wrote from the Theravada perspective (in his Visuddhimagga), and Vasubandhu, who wrote from the Sarvastivada perspective (in his Abhidharma-kosa). For Buddhaghosa all 37 practices occur in a single moment, the eka-citta, which corresponds to the moment when the four knowledges come to the cultivator. (The four knowledges are those of the path of stream-attainment, once returned, non-returned, and the ARHAT. ) For Vasubandhu the 37 practices constitute the entire path of Buddhist development.

Chan and Zen developed further emphasis on meditation. Although the Chinese word chan was originally a translation for the Sanskrit dhyana, in practice the Chinese term (and its Japanese equivalent, zen) represented more than the traditional three practices of sila, samadhi, and prajna. Zen practice includes these, plus the six perfections, the PARAMITAS, as well as a focus on gaining an intuitive understanding of the true nature of the practitioner’s mind. A further way to refer to enlightenment in Zen practice is satori, which indicates enlightenment, broadly speaking.

Ennin (Jijaku)

(794-864) Japanese Tendai leader

Ennin, the third chief-priest of Enryaku-ji, is famous in Japan as the student and successor of Saicho, who established Tendai as a major strain of Buddhist orthodoxy. He was born in Shimot-suke Province. Already a serious student of Buddhism, he traveled to Mt. Hiei to study Tendai Buddhism with Saicho at Enryaku-ji in 808. He subsequently spent a number of years in China studying both Tian Tai (of which Tendai is the Japanese version) and esoteric, Vajrayana, Buddhism. He believed the esoteric practices he had mastered to be of equal merit to the Lotus Sutra, the text so valued in the Tendai teachings.

Upon his return to Japan in 847, he began to introduce esoteric practices into Tendai. The positive response he received was manifested in his being chosen the new abbot of Enryaku-ji in 854. Through much of his life, he engaged in a struggle with another Tendai leader, Enchin, the head of another Tendai temple on Mt. Hiei. Only after Ennin’s death was Enchin able to move into a position of power at the monastery.

Ennin is equally famous for a journal he kept relating his nine-year travels through China. He witnessed in particular the Hui Chang persecution of Buddhism throughout China in 845 c.e. His eyewitness account is an invaluable record of this key event in Chinese Buddhism.

Enryaku-ji

Enryaku-ji is the head temple of the Tendai school on Mt. Hiei, northeast of Kyoto, Japan. It was founded by Saicho in 788 C.E., as part of his process of establishing the new Tendai teachings he had imported from China.

The site for the temple was carefully chosen, as the northeast was considered the direction from which evil inevitably arose. Hence, by placing his center on Mt. Hiei, Saicho was asserting its role as the protector of the nation in general and the capital in particular. Thus, after the capital was moved from Nara to Kyoto in 794, Enraku-ji was formally assigned the title "protector of the nation."

In 806, Saicho officially established the Tendai school, an event marked by his requesting the right to ordain his students using the Mahayana ritual and precepts, as opposed to the Hinayana precepts used at Toadai-ji in Nara, where all Japanese Buddhist priests were ordained at the time. Permission to erect a Mahayana ordination platform was approved just days after Saicho’s death and put into effect by his successors. Enryaku-ji went on to become the major Mahayana ordination center in Japan for centuries, and the training ground for such future leaders as Honen, Dogen, and Nichiren.

Esala Perahera (Buddha’s Tooth Day)

The Festival of the Tooth takes place in Kandy, in central Sri Lanka, and commemorates the sacred Buddha relic, a tooth of the Buddha, housed there. There is an elaborate procession on the full moon in the eighth lunar month. As the focus of devotion for all Buddhists in Sri Lanka, the Tooth Relic has deep symbolic meaning in Sri Lanka. It is a symbol of the nation itself, of sovereignty and self-determination.

Esala Perahera is a poya (fast) day that commemorates the day the Buddha taught his first sermon. It is also the day of his conception by his mother, Queen Maya, as well as of his teaching of the Abbhidharma (Abhidhamma) to her in heaven.

Ethics, traditional Buddhist

Buddhism has not developed a single, separate ethical system as a philosophical category. Rather, ethical considerations spring forth from existing Buddhist concerns. We may call these core concerns, since they are ideas with which Buddhist thinkers have wrestled for centuries. Buddhist ethics is in fact a secondary ordering, a "second-order reflection," of other systems. Of more vital importance to Buddhist writers is the person’s moral standing, and as with all religious systems ethics are derived from moral considerations.

Because morality is anchored in culture and historical context, the various Buddhist interpretations of moral behavior must be understood within their cultural contexts. Ethics are meaningful only as they are practiced, and they are practiced in various cultural settings by different peoples.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF BUDDHIST ETHICAL CONCEPTS

Buddhism started in the fourth century b.c.e. with the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama (c. 490-410). Siddhartha was born as a prince into the Sakya tribe in northern India. Despite living in the midst of great luxury he was able to observe his surroundings carefully. He noticed the universality of birth, aging, old age, and death. After leaving home to devote himself to spiritual goals,he announced, at age 35, that he had seen through this condition and attained nirvana.

Buddhism developed in response to the highly ritualized vedic religious practices then dominant in India. Vedic religion was controlled by brah-mans, hereditary priests. There were also many competing teachings, including skeptics and individual ascetic teachers. Buddhism was at that time simply one competing system of many. Because of this, there were some ideas that Buddhism shared with the other groups, and others that were unique. The Buddha rejected such practices as animal sacrifice, complex ritual, and the caste system. On the other hand, he adopted these key conventional ideas:

Dharma: This indicates a universal law that governs the universe. It also indicates the teachings of the Buddha, which reflect the operation of the universe. One who lives according to the Dharma will live a righteous path, in accordance with the Buddha’s teachings. This natural law of Dharma was not created by the Buddha; he simply discovered and described its operations. To follow the Dharma is a moral choice.

Karma: This is the idea that all actions have consequences in the moral realm. There is a dimension of action that is moral, not simply material. And all people are part of this system. Since moral action is needed in order to achieve nirvana, someone following the Buddha’s Dharma must recognize the moral significance of all actions. Rebirth: Rebirth means the return in another body, another identity. That identity may be better or worse, depending on moral behavior in the previous existence. This idea of a string of existences, all linked by karma, was prevalent in India and became a part of Buddhist thought.

In addition to these existing concepts the Buddha naturally developed his own. These include the following novel ideas:

The Four Noble Truths: The Four Noble Truths state the Buddha’s fundamental understanding of reality. Suffering (dukkha) is part of life. Suffering is caused by desire (tanha). There is a way to end this suffering, and that way is nirvana. In order to achieve nirvana the person should follow the Eightfold Path.

The Middle Way: The Buddha taught that people should not go to excess. Since he had tried extreme asceticism as well as extreme hedonism, he felt a "middle way" was the only method to cultivate the moral life. This led to the formulation of the Noble Eightfold Path:

Right view

Right resolve

Right speech

Right action

Right livelihood

Right effort

Right mindfulness

Right meditation

These eight are traditionally grouped into three parts: morality (sila), concentration (samadhi), and wisdom (prajna). View and resolve lead to wisdom. Speech, action, and livelihood concern morality. And effort, mindfulness, and meditation relate to the development of samadhi, or meditative calm. This list describes the ideal Buddhist: one who is aware of wisdom, attempts to follow a moral life, and uses meditation to gain spiritual progress.

The Precepts: In addition to the threefold description of morality (sila) given in the Noble Eightfold Path, there are detailed descriptions of moral codes found throughout the Buddhist literature. The most basic, the Five Precepts (panca sila), are the five elements of right action: no killing, no stealing, no sexual immorality, no lying, and no taking of intoxicants. These five are the basic precepts that all lay people in Buddhism follow. Monks, nuns, and others preparing for the sangha have additional lists found in the Pratimoksa.

Virtues: The precepts listed actions that followers were not allowed to do. In contrast, virtues are lists of positive traits. There are countless lists of virtues and vices in Buddhist literature. But in the earliest period the virtues can be narrowed down to the following:

Alobha (unselfishness): The person acts without selfish desire.

Adosa (Benevolence): The person wishes goodwill to all living beings.

Amoha (understanding): The moral person understands human nature as described in the Four Noble Truths.

The Four Sublime States (Brahma-viahara): There were in addition some states associated with meditative practice. These four subtle conditions required constant application and cultivation as a Buddhist: love (metta), compassion (karuna), gladness for others (mudita), and equanimity (upe-kkha). The literature gives directions about how each person can develop these four qualities through conscious application, for instance, by spreading positive feelings of karuna (compassion) to everyone in one’s surroundings.

A Middle Ground: Finally, traditional Buddhist ethics stress the absolute importance of leading a moral life. Buddhism revolves around gaining wisdom and translating that wisdom into action. Buddhist thinkers argued from the very beginning against dogmatic positions and favored the individual’s using his or her innate powers of reasoning. They rejected eternalism (sas-satavaada) as well as nihilism (sabba atthii ti), hedonism as well as self-mortification. Such extremes, they taught, led away from the development of wisdom and self-knowledge. Buddhism from the very beginning emphasized finding the middle ground between extreme views.