Daodejing (Tao Te Ching)

The Daodejing, the Classic of the Way of Power, is perhaps the best-known book of Chinese Daoism and is a classic of world literature and spirituality. It is the most widely translated work from Chinese, translated into English alone more than 30 times. It is organized into two books that total 81 topics. The work was originally simply called the Laozi, the book of Laozi. But by the second century c.e. it was also called the Daodejing. The first half is in fact the Dao Jing, the second the De Jing. These titles do not indicate significant themes of the two parts; they reflect simply the first words in each half. At 5,000+ Chinese ideographs the Daodejing is a relatively short work.

The Daodejing is traditionally attributed to Laozi, who lived roughly around the time of Confucius, in the fourth-fifth centuries b.c.e. The work is clearly an anthology, a collection assembled from various sources and by different individuals. What unites the passages is that they relate to the school of Daoism (dao jia), one of the competing philosophic schools of the period. in this school the idea of Dao is central. Dao is inexpressible. it is the source of all things and events. it prexisted the universe. it transcends distinctions and is the key to all possibilities.

This foundational work in Chinese spirituality is well worth reading and rereading. it is difficult to top this opening:

The Dao that can be told of is not the eternal Dao; The name that can be named is not the eternal name.

The Nameless is the origin of Heaven and Earth;

The Named is the mother of all things. Therefore let there always be non-being so we may see their subtlety, And let there always be being so we may see their outcome.

The two are the same, But after they are produced, they have different names.

They both may be called deep and profound.

Deeper and more profound, The door of all subtleties!

(Wing-Tsit Chan, A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy [Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1963] 139)

Daoism (Taoism)

Daoism as a formal, organized religion is not as widespread or popular as other Chinese religions, for instance, Buddhism or Christianity. However, as a system of concepts, a way of interpreting the world, Daoism exerts a strong pull on many people. And in Chinese culture, as well as many other Asian cultures, Daoism continues to live in a range of popular level practices, from medicine to martial arts to ritual feasts in villages.

Daoist teachings focus on humanity’s relationship with nature. unlike in many religious systems, there is no all-powerful deity figure who created the universe. All phenomena, instead, enter into existence through a process of constant multiplication and decay. Tuning into this process is a major goal of the Daoist practitioner. Daoist teachings also include political considerations, such as the correct role of the ruler in regard to the subjects, as well as issues of correct diet and regulation of the body.

Daoism is the most uniquely Chinese religion, and yet it remains a subject of great misunderstanding. Some see it as identical with the early texts Daodejing and Laozi. others see it as an imitation of Buddhism.

There are four periods in Daoist history: proto-Daoism, classical Daoism, premodern Daoism, and contemporary Daoism.

PROTO-DAOISM

In proto-Daoism there was no formal religious organization. The earliest "Daoists" were most likely shamans who helped people in this world understand "secret" or hidden phenomena. Still, many core Daoist ideas and beliefs formed at this time. Several classic books on philosophy and mysticism were written in this period, including the Laozi, Zhuangzi, and Neiye.

LAOZI

Sima Qian, an early Chinese historian, stated that Laozi was an "archivist" who lived in the Zhou dynasty (1027-221 b.c.e.) and was one of Confu-cius’s teachers. Laozi retired and journeyed west but was stopped at the Hangu Pass by Yin xi, the gatekeeper. Yin xi asked him to write a text containing his philosophy. The result was the Daodejing, the Scripture of the Way and Its Power.

The Daodejing, or Laozi, is a terse statement of important philosophical positions. It explains the creation of the universe and the forces at work in it.

The Daoist myth states that Laozi continued on to India and appeared there as Sakyamuni, the Buddha. He then traveled farther west and became Mani, the founder of Manichaeanism, a dualistic Christian sect.

ZHUANGZI

Zhuangzi was a Daoist leader who lived a few hundred years after Laozi. The classic that is known by the philosopher’s name has never been used much by Daoists. Instead it is important because it explains the concept of the sage, the enlightened being who can live without being fettered by social and cultural conventions. This perfected person was called a zhenren, a "true person." In this image, Daoism becomes a personal spiritual quest.

NEIYE

A third proto-Daoism text is the Neiye, "inward training," which is a smaller section of a larger work, the Guanzi. The Neiye is the first of a long line of Daoist writings to focus on such techniques for longevity as breath meditation. In the inward training the practitioner focuses on internal energy, and especially the QI or "vital energy." The refined form of qi is jing, or "essence." The person who can cultivate jing can improve the circulation of qi in the body. Through cultivation of such qi the person becomes attuned to the energy of the cosmos, the universal Qi.

CLASSICAL DAOISM

Classical Daoism began in 142 c.e., when Zhang Daoling started the Way of Orthodox Unity, the first organized Daoist religion. In this period two other important Daoist groups started as well: Shangqing Daoism (the Way of Highest Clarity) and Lingbao Daoism (the Way of Numinous Treasure). Classical Daoism took general shape in this period as an organized religious spirit. It developed fixed rituals and important texts. Classical Daoism thus corresponds roughly with medieval Chinese history—from the Han (221 B.C.E.-220 c.e.) through the Tang (618-906 c.e.) dynasties. Politically, Daoism reached the peak of its influence as the official religion of the Tang during the reign of the emperor xuan Zong (713-756). During the Tang, Daoism also spread into neighboring countries, such as Korea, japan, and Vietnam. Several important new Daoist religious movements developed in China during the classical period.

ZHENGYI DAO (WAY OF ORTHODOX UNITY)

The end of the Han dynasty saw several revolutionary movements spring up. Zhengyi Dao (or, in another name, the Way of Celestial Masters— Tianshi Dao) was founded in 142 c.e. by Zhang Daoling, in Sichuan, in far western China. Zhen-gyi Dao was a theocracy—civil and religious administrations were the same. The group also used public ritual to expatiate or atone for sins. It taught that Laozi was a god. All offices in Zhen-gyi Dao were hereditary. So eventually Zhang Daoling’s son and grandson took over. Zhang Lu, the grandson, finally surrendered power to the revolutionary leader Cao Cao in 215 c.e. At this point all Zhengyi followers dispersed to different regions of China.

SHANGQING (WAY OF HIGHEST CLARITY) SCHOOL

This movement arose among the higher classes in southern China, in the 300s c.e. The pronouncements of a Daoist immortal, Lady Wei Yang, who khad lived on Mt. Mao near Nanjing, in central China, were collected by Tao Hongjing (456-536 C.E.), who founded the Shangqing school.

Shangqing Daoism was not a communal movement. instead it emphasized personal self-cultivation and the deities of the stars and the Big Dipper. These gods were seen to enter the person’s body during meditation. They then helped the cultivator to transform into a celestial immortal. The goal, then, was immortality.

THE LINGBAO (WAY OF NUTREASURE)MINOUS

The Lingbao were probably originally spirits or shamans who guarded certain places. Later, Lingbao referred to talismanic objects such as small books, chants, or diagrams that had spiritual powers of protection. The Lingbao school was centered around belief in five sacred diagrams, one associated with each of the five directions. These diagrams were in a collection of texts written by Ge Chaofu and made public in 401 c.e.

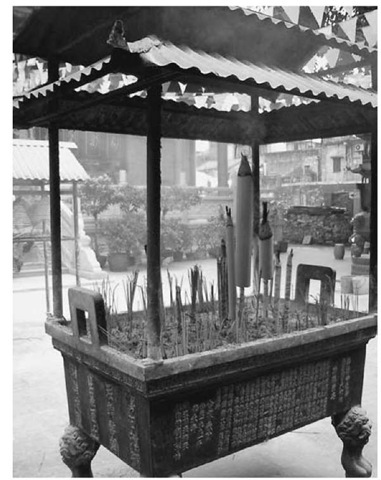

Large incense burner, Daoist temple in Guangdong, China; names of donors are listed on the side of the burner

Numinous Treasure Daoism is clearly influenced by Buddhist ideas. The talismans and charts were said to help all sentient beings to attain salvation, which is a key goal of Buddhist practice. Lingbao liturgies and rituals showed a way to save people from a complex series of hells and purgatories where people suffered for karmic sins. All these were Buddhist ideas. Daoism also borrowed the idea of taking precepts or vows to abstain from meat and sex.

Lu Xiujing (406-477) was the seventh celestial master. He standardized the Lingbao texts and broke Daoist ritual into three types: ordinations (jie), fasts (zhai), and offerings (jiao). These three types were all practiced at the imperial courts whenever Daoism was in favor. Lu also developed popular rituals. Today jiao is the main kind of public ritual performed by Daoist priests.

PREMODERN DAOISM

The premodern period of Daoism began with the Song dynasty (960-1279). In this period the borders between Buddhism and Daoism became blurred. There was another kind of influence at work as well: local cults. All over China people worshipped local heroes and gods. Such worship practices became mixed into the Daoist hierarchy of gods.

In this period the most significant new movement was Quanzhen Dao (the Way of Complete Perfection), which was started by Wang Chongyang (1112-70), a former official of the Liao dynasty (907-1125). Quanzhen is significant today as one of the two organized forms of Chinese Daoism still practiced. Quanzhen was based on Chinese alchemy ideas. However, over the years its focus has shifted more to community religion. It is also a blend of Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist ideas. Quanzhen was most influential under the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368). Qiu Chanchun (1148-1227), a famous Quanzhen leader, visited the Mongol emperor Genghis Khan and debated Buddhists at his court. Quanzhen had influence at court, clearly. However, such political support could come and go: a later debate with Buddhists in 1281 was lost.

Daoism later made a comeback during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). It was during the Ming, in 1445, that the Daoist Canon (Daozang), or collection of Daoist written works, was first compiled, under the Yongle emperor. This collection included around 1,500 different texts, including hymns, liturgies, recipes, and myths.

CONTEMPORARY DAOISM

The final period, the modern or contemporary, started with China’s modernization in the late 19th century. Daoism, along with Buddhism and Confucianism, gradually lost influence among China’s educated elite. By the time the last empire was overthrown, in 1911, the educated classes were clearly looking for alternatives to traditional religious systems of thought. Institutional Dao-ism, including its system of monasteries and rituals, experienced financial problems.

Today Daoism survives in three major ways. First, it remains a powerful system of ideas and mysticism. Such a cultural network influences Chinese culture in many areas, for instance, in martial arts training, art, and literature.

A second form of influence is institutional. Daoism as an institution takes two forms today. First is Zheng Yi, or "Orthodox One," Daoism. Zheng Yi Daoists are individual Daoist teachers who pass their ritual knowledge to disciples. This is not a communal religious practice, although Zheng Yi Daoists do officiate at local community temple celebrations. Quanzhen Daoism, in contrast, is communal and, in a limited way, monastic. There are networks of Quan Zhen temples now in Hong Kong and China that perform com-munity functions such as holding funerals and celebrating major holiday.

Large stone stele, or memorial, placed on a turtle, symbol of the East, in the Qingyang gong, a Quanzhen Daoist temple in Chengdu, Sichuan, western China

A third form of Daoism active today is best understood as "popular Daoism." There are ritual specialists who, though not formally ordained or trained as Quan Zhen or Zheng Yi Daoists, are nevertheless called "Daoists" in many villages and towns. These specialists are called on to perform rituals at village feasts and important celebrations. They are respected, and paid, because of the ritual knowledge they possess. Such specialists may also tell fortunes and dabble in FENG shui. Other people offer Daoist knowledge in the marketplace, including divination using the Book of Changes (Yi Jing) and Chinese medical advice based on Daoist principles.

Daoist alchemy

Daoism includes a number of intriguing practices, many of which can be considered more or less mystical, and at times highly esoteric (secret). Some of the most misunderstood of these traditions have been focused on transcending death and attaining "immortality." It has become common among scholars to label such traditions alchemy, a term usually associated with occult practices in the West.

One type of Daoism closely associated with alchemy is "hermit Daoism." As might be surmised, hermit Daoism is particularly associated with mysterious "hermits" who lived in seclusion far off in the mountains. in their hidden dwellings, these hermit alchemists spent their days working with the cosmic forces in the body, practicing intense meditations, and concocting (and consuming) magical elixirs intended to promote longevity or even to enable the practitioner to transcend the mortal realm.

These practices and the ideas behind them are not necessarily as far-fetched as they may appear. Daoist alchemy is rooted in important philosophical texts (e.g., the Book of Changes and Daodejing), and probably dates to ancient—even prehistoric— shamanistic practices that formed the original basis of Chinese culture. In whatever form we find it, Daoist alchemy is premised on understanding and acceptance of life and death, sickness and health, and a conviction that these dualities can be transcended. Such views are fully in keeping with the ideals of "free and easy wandering" and radical freedom (even invulnerability) espoused in the Daoist sage Mencius’s great work Zhuangzi.

ORIGINS AND BASIC FEATURES OF ALCHEMY

The Chinese term most often translated as "alchemy" is jindan ("gold-cinnabar"), undoubtedly because it names the two principal ingredients in most alchemical elixirs.

Daoist alchemy was encouraged by techniques of metallurgy. China was one of the first ancient civilizations to attain high levels of development in the casting and smelting of bronze. Some of the earliest masterpieces of Chinese art were the great bronze vessels of the Shang (1766-1027 b.c.e.) and Zhou (1122 B.C.E.-256 b.c.e.) dynasties, and the earliest dynastic histories speak of such vessels as among the most treasured royal objects. Such vessels (often tripods or cauldrons) were only used in official sacrificial ceremonies. By serving as containers for sacrifical offerings, the vessels themselves became sacred; they became bridges to heavenly realms. The effect was to engender a deep-seated cultural association between prized bronzes (cauldrons and the like) and the divine. it is but a short step to putting such sacred vessels to other uses such as preparing special mixtures for attaining a divine state of immortality.

Daoist alchemy essentially shares the same theoretical basis as most Chinese medicine. Since the Chinese have generally not maintained a strict separation of "mind" and "body" (both were thought to be composed of the same essential stuff), it was not difficult to conceive of survival after earthly life in some sort of transcendent bodily form. Daoists speak of the body as comprising three forces or life principles: QI (matter-energy, "breath"), jing ("essence," often equated with semen), and shen ("spirit," or more appropriately, "consciousness"). Each of these principles is also present in the larger cosmos. in such a cosmos it is relatively easy (at least theoretically) to transform from one level to another; such changes are essentially changes in form, not in substance.

"IMMORTALITY"?

The goal of Daoist alchemy has long been said to be "immortality," which referred to more than a simple "deathless state." Daoist "immortality" could be understood as physical, as a type of afterlife beyond the mortal body (as pure "spirit"), or perhaps a more mystical sense of merging with Dao. The latter would seem to be based on mystical experiences in which the practitioner realized she or he would never lose her/his true identity, even in physical demise. In some later forms of Daoism, the immortals ascend to the heavenly realms, where they take their places in an elaborate bureaucracy.

The most common Chinese term for "immortal" is xian, a word composed of the characters for "human being" (ren) and "mountain" (shan), making for a more or less literal translation of xian as "mountain man." In some respects this is actually a rather apt translation when we bear in mind the prominent role mountains have played in Daoist lore. Some scholars have tried to avoid the problematic associations with the term immortal by translating xian as "sylph," originally a Latin term that denotes a type of fairy (often female) supposed to inhabit the air. However, this rhetorical move conveniently avoids the whole matter of death and how it is to be overcome, the main Daoist concern in alchemical practice. The recent scholarly consensus is to stay with immortality for the sake of continuity with the understanding that Daoist "immortality" might best be conceived as a type of transcendence and transformation.

TYPES OF ALCHEMY

It has become customary for scholars to distinguish two forms of Daoist alchemy: "external alchemy" (waidan) and "internal alchemy" (neidan). "External alchemy" focuses on preparing various herbs, drugs, and elixirs that are consumed in order to prolong life or achieve immortality. There is some indication that these procedures were the outgrowth of the search for a way to turn baser substances into gold, the guiding idea in Western alchemy as well. By contrast, "internal alchemy" is a path of meditative cultivation that includes strict moral discipline, a regimented diet, and specialized exercises to nourish and purify qi.

"External" and "internal" alchemy were never truly separate in ancient and medieval China. In addition, various learned scholars (e.g., Ge Hong, 283-343) were deeply involved in alchemical pursuits. Toward the end of the Tang dynasty (618-906), however, "internal" alchemy was predominant, in large part because of the numbers of adepts who died of poisoning after consuming cinnabar elixirs. Nonetheless, it is helpful to consider both forms of Daoist alchemy separately with the understanding that aspirants engaged in practices from both.

"EXTERNAL ALCHEMY" (WAIDAN)

Although "external alchemy" is undoubtedly a very ancient practice, the first clear evidence of it is from the pre-Han and Han (206 B.C.E.-220 c.e.) eras with the rise of a certain class of proto-Daoists usually called "fangshi" (lit. "Masters of Techniques"). A very eclectic group, the fang-shi were essentially magicians and thaumaturges ("wonder workers") who had great reputations among the Chinese populace and were often sought after by various rulers.

Among the most famous of the fangshi was Li Shaojun (d. 133 b.c.e.), a powerful sorcerer who allegedly persuaded Emperor Wudi (r. 140-87 b.c.e.) to permit alchemical experiments that included invoking the aid of the Stove God in the transformation of cinnabar mixtures. The purified cinnabar concoction would be fashioned into special vessels and those eating from such dishes would be assured of immortality. Although his techniques differed from those of later alchemists, in the case of Li Shaojun, we clearly see evidence of someone engaged in alchemical practices aimed at transcending the bounds of mortal life. By the late Han and the ensuing "Period of Disunity" (220-589 c.e.), small groups of wai dan practitioners were widespread throughout China.

Followers of the Way of wai dan needed to prepare rather rigorously. Such training would typically include progress in various forms of meditation, calisthenics (e.g., qigong), and strict ethical striving. Serious Daoists have consistently maintained that pursuit of immortality required detachment from sensual desires and the purging of negative attitudes such as hatred, which were considered harmful to the aspirant. only with a firm foundation made strong through such cultivation could one actually begin procuring and mixing the ingredients necessary for the elixir that would confer immortality.

Actual consumption of an elixir might have any number of effects, depending on its potency and on the adept’s constitution. in theory it could transform the alchemist’s body into one of pure light and air, enabling him to soar into the heavens to join the other immortals. In practice, though, the effects were rather different. Texts indicate that the elixir was to be taken in small doses at regular intervals and accompanied by a special diet. Some alchemists, however, took large doses that invariably caused their deaths. in small doses elixirs seem to have had a sedative effect, aided the breathing, warmed the body, and even promoted hair growth. In addition, those who took the elixirs experienced heightened sexual energy, general sensory arousal, and possibly even hallucinations. Perhaps the most important side effect was the preservation of bodily tissues. The bodies of those who died of elixir consumption resisted normal decay, retaining a lifelike appearance that may have been taken as direct proof of immortality.

External alchemy continued to be practiced throughout the medieval period, yet during the latter sixth century there is evidence of growing skepticism in some alchemical circles. Thus, for instance, we read of instances when condemned prisoners facing execution were used as guinea pigs to test various elixirs. Nonetheless, the Way of waidan enjoyed something of a renaissance in the Tang dynasty (618-907 c.e.). During this remarkable period of cultural flowering many wealthy and powerful patrons employed professional alchemists who worked to perfect their techniques. Yet invariably there were many poisonings. In fact, during the Tang more emperors died of ingesting alchemical elixirs than in any other period. The increasing evidence of failure provoked a major rethinking of the entire art of alchemy and the eventual decline of waidan as a viable practice.

"INTERNAL ALCHEMY" (NEIDAN)

The Way of "internal alchemy" developed originally from meditation techniques used by practitioners of "external alchemy." We can see such ideas at the fore in the life and work of Ge Hong. Ge Hong was a well-known scholar who actively sought ingredients for concocting elixirs but who also led a disciplined personal life. He was an accomplished practitioner of complex meditations, notably techniques of visualization known as shouyi ("Guarding the One"). In his masterpiece, the Baopuzi, he writes:

Guard the One and visualize the True One; then the spirit World will be yours to peruse!

Lessen desires, restrain your appetite—the One will remain At rest!

Like a bare blade coming toward your neck—realize you Live through the one alone!

Knowing the one is easy—keeping it forever is hard.

Guard the One and never lose it—the limitations of man will Not be for you!

On land you will be free from beasts, in water from fierce Dragons.

No fear of evil spirits or phantoms, No demon will approach, nor blade attain!

In this and other passages Ge Hong seems to promise freedom and superhuman powers merely from practicing the mysterious meditation techniques rather than ingesting actual elixirs. As time went on, alchemists increasingly began to turn to such practices as offering an alterative path to ultimate transformation.

It is really only in the late Tang and the period immediately following the dynasty’s collapse that we find Daoist thinkers self-consciously distinguishing the Ways of "external" and "internal" alchemy. In part this was due to growing skepticism among alchemists that immortality (in at least the grossest, most literal sense) was even possible. under the steady influence of Buddhism, some alchemical thinkers concluded that immortality properly construed was really liberation (nirvana) from the beginningless cycle of life and death (samsara). Others took a more rationalist view and maintained that so-called immortality was really about cultivating health and longevity. In their entertaining such notions, we see that many Daoists in the later Middle Ages were actively reinterpreting their received traditions. Most also began to emphasize the various meditations and systems of bodily exercise that had traditionally been regarded as adjunct practices in the concocting of elixirs.

It is often difficult to decipher instructions for practices of neidan, since alchemy is generally an esoteric tradition passed on only to initiates who have been trained in its secret lore. As such, the language typically found in alchemical texts is cryptic and highly symbolic, resembling the "twilight language" of Hindu and Buddhist tantras. The guiding principle seems to be visualizing the body and its energies as the furnace and cauldron in which the elixir of immortality (the "Golden Elixir" or "Golden Flower") is purified. Essentially then, the same steps in "external alchemy" are still performed albeit internally.

Actual methods of neidan seem to vary tremendously but share a view of the body as being divided into three "cinnabar fields" (dantian) located in the abdomen, chest, and head. Practitioners would engage in special techniques of breathing, visualizing light (qi made visible) and then circulating it through the "cinnabar fields" in what was sometimes called a "microcosmic orbit." With practice, this might be extended to the limbs in a "macrocosmic orbit." Other practices involved nourishing the yin-yang energies of the body and uniting them to create a "spirit body" (often described as the "embryo") that would depart the body at death and live on beyond the gross material realm.

Neidan probably reached its height in the period from the late 10th to mid-14th centuries during the Northern and Southern Song (9601279) as well as the Yuan (1279-1368) dynasties. one important "internal" alchemist was Zhen Xiyi, who allegedly studied under Lu Dongbin. The most important master of neidan, though, was Zhang Boduan (987-1082), a government official who received revelations from Lu Dong-bin and retired to alchemical pursuits. He earned great fame for a collection of poems entitled the Wuzhen pian (Awakened to reality). Other practitioners founded rival lineages that used other techniques. Despite their differences, however, nearly all practitioners of neidan agreed that the proper Way required physical and psychological cultivation. Thus, we can say that Daoist alchemy became a means of training both mind and body or, as some scholars have recently put it, a "bio-spiritual" tradition.

DAOIST ALCHEMY TODAY

Daoist alchemy (particularly neidan) is still actively practiced. It has transformed over the years and can now be found most obviously in the various movements of qigong. Qigong is a generic term for various complex systems that include meditation, gymnastics, martial arts, and breath control. Although it has ancient origins, it only developed into an integrated system during the mid-20th century. It is in this form (along with the related art of Taijiquan) that teachings and practices based on methods of "internal alchemy" have been most often made available to Western students. The stated aims of both arts are to promote physical and mental balance, health, and so on, although reports of developing supernatural powers (e.g., clairvoyance, telepathy) are not uncommon.

The renowned psychoanalyst C. G. Jung (1875-1961) was very interested in Western forms of alchemy, and in conjunction with his friend Richard Wilhelm (1873-1930), a renowned orientalist, published a new translation of an alchemical treatise entitled the Taiyi jinhua zong-zhi (Supreme unifying secret of the golden flower) with his own commentary. The resulting volume (translated into English as The Secret of the Golden Flower) has become a classic of Jungian psychology and has opened up the exploration of Daoist alchemy to many contemporary people.