China-Hong Kong, Buddhism in

Although Hong Kong’s history as a large city began only in the 1840s, when Britain gained possession and built it into a strategic colony, Buddhism had a presence in the area long before the British arrived. Buddhist monasteries and nunneries coexisted with local temples dedicated to local gods, as well as Daoist institutions. until the modern era, however, these institutions had limited interaction with the local people; they tended to be isolated buildings with monastics leading their own lifestyles. Despite the government’s open preference for Christianity during most of Hong Kong’s modern history, Buddhism today remains a major presence in Hong Kong society. The number of active Buddhist believers has been estimated at between 500,000 and 1 million (of a total of nearly 7 million), although many other inhabitants engage in Buddhist rituals on an occasional basis. In particular, most non-Christian funerals today are invariably Buddhist. It is a good bet that Buddhism will continue as a major part of Hong Kong’s social fabric and cultural sensibilities.

The earliest proof of Buddhism in Hong Kong is found in three temples. The oldest are the Beiju Si and Lingdu Si in the New Territory towns of Tuen Mun and Yuen Long, respectively. They were said to have been renamed by a monk, Bei Du, in 428 c.e. Hence they were in existence before that time. Their locations in the New Territories, near the coastal forts guarding the approaches to the Pearl River, reflect the importance of the sea trade throughout most of China’s imperial history. Interestingly, both of these early temples probably housed communities of unmarried, vegetarian women during parts of their histories. And the Bei Du temple was at one point (1829) converted into a Daoist monastery; it later reverted to a Buddhist institution in 1926. It has been called Qing Shan temple ever since.

Another well-known temple, the Ling Yun, was also a Buddhist nunnery for a period. Built originally between 1426 and 1435, it was in turn a private villa before reverting to a nunnery in 1911.

In the premodern period the landscape in Hong Kong was fluid and informal. Temples often switched between Buddhist and Daoist affiliations, and temples often converted to nunneries, as mentioned. Temples were found in both urban and rural settings. Those in the rural New Territories were basically retreats for religious hermits. Those in urban settings were used for ritual services. There was no strong sense of belonging to a single "Buddhist" religious community. Instead, different institutions lived independently.

In 1957, there were 83 Buddhist institutions in the whole of Hong Kong; a large part, 89 percent, were hermitages based in the New Territories island of Lantau. And the majority of those, some 70 percent, were not monasteries but were female-led nunneries, called zhai tang, or "vegetarian halls." These halls served as places of solace for women who refused to marry (known as zhush-unu), as well as lower-class, migrant, or otherwise unattached women who would otherwise have led a precarious life.

The early monasteries were not large public institutions, as were often found in other parts of China. Instead, they were smaller temples informally run by clergy and lay supporters together. ownership and management responsibilities for these temples were passed from generation to generation in a kind of inheritance system.

THE BRITISH AND BUDDHISM

In 1841 the first governor of Hong Kong, Captain Charles Eliot (1801-75), proclaimed that "the natives of the island of Hong Kong and all natives of China thereto resorting, shall be governed according to the laws and customs of China, every description of torture excepted." The government went on to pursue a policy of benign neglect of the spiritual aspects of Chinese society. The Chinese population was generally left to fend for itself, and this included the establishment and management of Buddhist institutions. if any care was taken with regard to religious issues, it was to focus only on Christianity.

There was a minimal government structure to deal with Chinese society. The secretary for Chinese affairs was responsible for advising on issues of Chinese culture. In 1919 this official was put in charge of religious institutions as well. in fact the government’s interest extended only to registration and landownership, and not to involvement with religious content or forms.

In 1928, a law that dealt with Chinese temples, the Chinese Temples Ordinance, was introduced. In order to prevent misuse of temple funds, all local temples (with the exception of five established ones) were put under a Chinese Temple Committee. The committee was in fact mainly composed of leading Chinese community leaders concerned with the proliferation of exploitive religious practices. Today the committee is concerned largely with registration of temples.

BUDDHIST REVIVAL

When a vigorous revival movement took hold on mainland China, Hong Kong was soon affected. in the 1930s new institutions such as the Tung Lin Kok Yuen introduced a new type of Buddhism to the local population, one characterized by active participation in society. The revival started with the visit of important clergy, such as Tai Xu in 1920. It was also evident in the establishment of new institutions and the restoration of others. As in China, the Buddhist reform movement focused less on intellectual issues and more on institutional reform, often in the face of scorching criticism from such Chinese intellectuals as Hu Shi.

Tai Xu visited Hong Kong seven times, beginning in 1910 and ending in 1936. However, he formally invoked the Buddhist revival only when he visited in 1920. Tai Xu’s followers soon arrived to lecture and educate the local population in Buddhism. And unlike in the traditional model, in which lectures were held in monasteries, from the 1920s lectures were increasingly presented in public forums such as playgrounds, parks, and cinemas.

Many of the new Buddhist institutions were built in the rural areas, especially Lantau Island, Shatin, Tsuen Wan, and Taipo, in some cases along the rail lines. By 1927 three temples, the Qingshan in Tuen Mun, Lingyun in Yuen Long, and Po Lin Monastery on Lantau, were regularly performing ordination ceremonies for new clergy.

The role of public lay supporters was redefined at this time. Public ordination ceremonies were held to admit lay followers as lay disciples (guiyi dizi) of the Buddha, a significant innovation for Hong Kong Buddhism. Tai Xu held such a ceremony during his visit in 1928 in which he admitted 3,000 as disciples.

This social atmosphere culminated in the establishment of the Hong Kong Buddhism Study Association. Its roots lay in the Buddhist Society, a private group formed in 1916. The group’s purpose and title were revised in 1931 to the Buddhist Study Association. Another important institution, the Tung Lin Kok Yuen (Eastern Lotus Enlightenment Garden), was established in 1935 by Lady Clara Ho Tung (1875-1938) with the goal of becoming the center of Buddhist community in Hong Kong. The society and the Yuen coexisted well and led directly to the formation of the Hong Kong Buddhist Association in 1945.

THE HONG KONG BUDDHIST ASSOCIATION

The association was formed only after the end of the Anti-Japanese War in 1945. It first took over a former Japanese Buddhist temple, Dongbenyuan, in the urban district of Wanchai. The Japanese monks residing in the temple, seeing defeat as imminent, decided to donate their temple as long as it remained a Buddhist institution. They transferred ownership, on August 16, 1945, to two lay Buddhists who were also active as leaders of the Tung Lin Kok Yuen, Chen Jingtao and Lin Lingzhen. In 1967 the association moved to larger premises on Lockhart Road, where it continues today. The association’s Web site claims a membership of 10,000 people, including clerics.

The association’s leader, the Venerable Kok Kwong, is the de facto leader of Hong Kong’s Buddhists, although other groups are not bound to follow his leadership. In fact, his major role is as a visible presence at formal ceremonies. He is also a delegate to the National People’s Congress, a national-level role. In his rare public statements he has tended to support Beijing’s policies strongly.

China-Taiwan, Buddhism in

Chinese Buddhism in Taiwan has thrived in the modern period. Taiwan is today a center of Buddhist development.

Scholars can document the existence of Buddhism in Taiwan only from the migration of Chinese fleeing to the island after the fall of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Many of the "monks" of this period were Ming loyalists who fled to the island in clerical disguise, and legitimate clerics were few in number and largely ignorant of Buddhist teachings. Those whose names appear in the records were noted for non-Buddhist accomplishments such as rainmaking, painting, poetry, and playing go. Most functioned as temple caretakers and funeral specialists and did not engage in teaching, meditation, or other Buddhist practices.

As the island became more settled, many more temples were founded, particularly around the capital city, Tainan. Despite this apparently vigorous activity, it is doubtful that very many of the monks and nuns who inhabited these temples had received more than the novices’ ordination, since there was no ordaining monastery in Taiwan, and only scant records exist of those who journeyed to the mainland to receive the full ordination.

In 1895, the Chinese government ceded Taiwan to Japan, and when Japanese troops arrived, they were accompanied by Buddhist chaplains. These were eager to establish mission stations in order to propagate Japanese Buddhism to the native population, but funding from their head temples was insufficient, and only a very small percentage of the Chinese population ever enrolled in Japanese Buddhist lineages.

In fact, one of the most notable features of the Japanese period is the effort of the local Buddhists to keep their Chinese identity and traditions. This period saw the institution of the first facilities for transmitting the full monastic precepts in Taiwan. Four temples established "ordination platforms," and the leaders of these temples, all of whom had received ordination at the Yongquan Temple in Fuzhou, transmitted their tonsure-lineages to Taiwan. ordinees from these temples went forth and founded other temples, giving rise to the "four great ancestral lineages" that defined and organized Buddhism during the Japanese period.

Even as Chinese Buddhism attempted to maintain its own distinctive identity, it still had to accommodate the government in some fashion, and so clergy and laity joined to form Buddhist organizations that functioned as governmental liaisons. The largest of these, founded in 1922, was the South Seas Buddhist Association, which operated until 1945.

The end of the Pacific war in 1945 saw the return of Taiwan to China, and in 1949, the mainland fell to the Communists and the Nationalists fled to Taiwan. All of these events kept the political and economic situation in turmoil, and Buddhist clerics experienced difficulty keeping their monasteries viable. A few monks of national eminence arrived, such as the Zhangjia Living Buddha (1891-1957), Bai Sheng (1904-89), Yin Shun (1906- ). They were the leaders of the newly revived Buddhist Association of the Republic of China (BAROC) and went to Taiwan for reasons that paralleled the Nationalists’: to use Taiwan as a base of operations until they could return home to rebuild Buddhism.

The BAROC mediated between Buddhism and the government in several ways: the government expected it to register all clergy and temples, organize and administer clerical ordinations, certify clergy for exit visas, and help in the framing of laws dealing with religion. In other areas, the BAROC confronted the government when it threatened religious interests. Two notable controversies concerned the failure of the government to return confiscated Japanese era temples to religious use, and the government’s obstruction of efforts to establish a Buddhist university.

Because the laws on civic organizations allowed only one organization to fill any single niche in society, the BAROC enjoyed hegemony until the late 1980s. Then, in 1989, the government no longer dealt with Buddhist monks and nuns separately, but registered them under their lay names as ordinary citizens. Thus, the BAROC was no longer needed to certify their status. That same year, a new law on civic organizations took effect, abolishing the "one niche, one organization" rule and opening the way for competition. In the ensuing period, other Buddhist organizations took root. Some grew out of preexisting groups, most notably Foguangshan and the Buddhist Compassion Relief Tzu Chi Association. Others were newly founded, such as Dharma Drum Mountain and Zhongtai Shan.

China-Taiwan, Daoism in

Daoism, as a major Chinese religion, is present in Taiwan at both official and unofficial levels. officially there are an organization of Daoism and a handful of strictly Daoist temples. Yet the number of worshippers in this official Daoist religious practice is dwarfed by those who follow Buddhism and other Chinese religions. unofficially, however, Daoism is an intrinsic part of popular religious practice in Taiwan. Indeed, popular religion in Taiwan, as well as China, is often termed "popular Daoism."

With the political and economic changes in contemporary Taiwanese society, the practice of maintaining shentan, or "spirit altars"—another term for Daoist temples—has become more streamlined than in traditional Chinese Daoism. As a result, Daoism in contemporary Taiwan is mixed with belief in the Buddha and additional folk beliefs common to southern China. These changes have the following background.

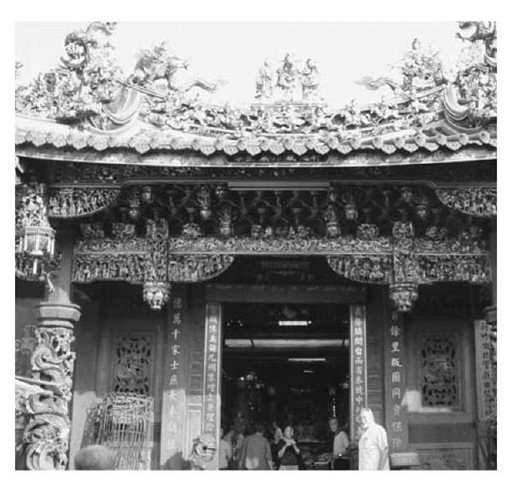

Chenghuang (City God) temple, built in 1748, Hsinchu (Xinzhu), central Taiwan (Institute for the Study of Religion, Santa Barbara, California)

Inhabitants of the border regions of southern China migrated to Taiwan island during the Chinese Middle Ages—that is, between the Tang dynasty (618-907 c.e.) and the Ming-Qing period (1368-1911 C.E.). By the late Qing Taiwan was nominally ruled by the mainland Chinese imperial regime, but with little actual control or presence. During the subsequent Japanese occupation (1895-1945 c.e.) a colonial policy of "forbidding Daoism and promoting Buddhism" predominated. After the defeat of Japan in World War II the regime then ruling China, the Kuomintang (KMT), also assumed power in Taiwan. The KMT authorities intentionally ignored Daoism for the sake of their own political purposes. The regime feared the accumulation of popular power anywhere in Taiwan. Because of such concerns the various Republic of China (ROC) Daoism associations offered no training in Daoism to their members, not even training in basic Daoist doctrine. The government feared that once the members became well educated, the ruling KMT authorities would ultimately lose control over the Taiwanese people. Therefore, the association headquarters functioned only to collect annual fees from the shentans, or temples, throughout the countryside. The consequence of this situation has been the entanglement of orthodox Daoist belief with Buddhist beliefs.

Excluding the small number of Christians in Taiwan today, most of the population can be considered as followers of popular religions. This term is widely used in academic and religious discussions today. However, few people have a correspondingly clear or distinct idea about the meaning of Daoism. In a broad sense most Taiwanese may be regarded as trustees of Daoism, whose number of adherents is several times that of Christianity in Taiwan. In spite of this, we must recognize that some forms of orthodox Daoist schools still exist at the local level in Taiwan, from north to south. These are the Zhengyi Pai (school), Chuanzhen Dao, Lingbau Daoism, and Lushan Pai. Among them Zhengyi Pai and Lingbau Pai may be regarded as identical lineages, judging from the titles of deities who at the beginning of any Daoist ritual are asked by the Daoist priest (daoshi or fashi) to descend from heaven to the altar to listen to the needs of the trustees. Compared with the other three schools, Chuanzhen Dao is said to be the newest branch for most Taiwan people because it has only recently spread from Hong Kong and mainland China to Taiwan, over the past two decades.

According to historical records, during the earliest Spring and Autumn period (722-481 b.c.e.) of Chinese history the ancient Chinese worshipped many deities, including heaven, the earth deity, ghosts, and ancestral spirits, in various forms. At the same time they expressed a unique understanding, a belief in the cosmos and the living world, through a symbolic system. During the Eastern Han dynasty, in 384 c.e., Zhang Daoling, considered the founder of Daoism, collected folk magic practices and put them into the context of this ancient Chinese religious culture. He combined these elements into an integrated whole that thereafter was called "Daoism." The clearest expression of Daoism gradually turned toward those aspects related to the search for eternal life through many empirically oriented methods and procedures.

There should be no doubt that Daoism itself, like other religions, has its characteristic pattern of logic. With the exception of Lushan Pai, which is concerned solely with traditional forms of Dao-ist magic to satisfy the daily needs of trustees, the contents and expression of the other branches of Daoism can be classified into the following five aspects: canonical texts, teachings, divine spells and documents, divination, and inner meditation inside the human body.

Despite their various forms of expression, the different schools are all based on an identical system of cosmology, theology, ontology, and life values. This common ground is the conceptual system of yin/yang and wuxing (the five elements). The former is a set of contrasting concepts about positive and negative attributes of material in the universe, and the latter is the fivefold classification of earthly materials: wood, fire, soil, metal, and water. Both are original and fundamental beliefs of the Chinese, who thought everything in the world (plants, animals, human, nonliving things included) could be fully classified, recognized, and conceptualized within the scheme of yin-yang/wuxing without exception and must be understood from this point of view. As a result the most ideal situations are "the harmonious union of yin and yang" and "the genetic relation of wuxing."

Compared with the other religions of the world, from ancient times to the present, these principles can still be seen as the most cardinal and unique core beliefs of Daoism, although Daoist culture has progressively changed and developed over the past 5,000 years. All beings are regarded as the by-products of the functioning of Dao. Because of this we can realize why the ultimate and transcendental is nothing but the unification of humans and heaven (tianren heyi), an ideal value constantly searched for by all Chinese.

China-Tibet, development of Buddhism in

The name Tibet is likely derived from the Mongolian word Thubet and is related to the Chinese Tufan and the Arabic Tubbat. Tibetans call their homeland Bod (pronounced with a "P" sound) and refer to it poetically as "the abode of snow." Tibet occupies the highest geographic region on Earth—"the roof of the world"—where people live at altitudes of 16,000 feet above sea level. Mostly it consists of a high plateau surrounded on three sides by massive mountain ranges; much of the area is uninhabitable except by the hardiest of Tibetan nomads and yak herders. However, it is not entirely a wilderness of snow and barren wasteland; there are numerous valleys and plains, pastures, fields, and woodlands, which create a great diversity of local growing conditions and wildlife habitat. The staple food, called tsampa, is made from roasted barley grains, ground into flour, and moistened with Tibetan butter tea.

The origins of the Tibetan people are unclear, especially since different peoples have migrated into the region during its history. one traditional origin story describes them as descendants of the Lord of Compassion Avalokitesvara, who in the form of a monkey took as his wife a mountain ogress. From their divine forefather, it is said, the Tibetans inherited gentleness, compassion, and a tendency not to talk more than necessary, and from their foremother, stubbornness, avarice, and love of meat.

There are varying accounts of the first king and the origins of the ancient Tibetan empire. one tells of a strange figure with long blue eyebrows and webbed fingers, an outcast from his native India who wandered north and appeared in the Yarlung valley. He encountered some farmers who asked him where he was from; not understanding their language, he pointed at the sky. Since the people of that time were said to worship the sky, they regarded him as a holy being descended from the sky and so acclaimed him as their ruler, hoisting him onto a chair on their necks to carry him to the village. So he was called the "Neck-Enthroned King," Nyatri Tsenpo. It was believed that the first seven kings after him had no tombs as upon death they ascended to their heavenly home by means of a rope of light that stretched from the crown of their head to the sky. In the life of the eighth king, however, this rope was accidentally cut and after that the kings of Tibet were buried in tombs.

Tibet enters into known history in the seventh century under the dominance of the Yarlung dynasty and the rule of King Songtsen Gampo (605?-649). At this time Tibet was surrounded by the Buddhist cultures of northwest India, Nepal, Central Asia, and China. Ironically, the people among whom Buddhism was to take such hold first appear in historical records as a fierce invading force known as "the Red-faces," a reference to the fact that their soldiers painted their faces with red ocher. The Tibetan empire was ruled from the seventh to the ninth centuries by three kings, who are traditionally known as the Dharma-kings or religious kings: Songsten Gampo (c. 618-650), Trisong Detsen (c. 740-798), and Relbachen (815-836).

Songsten Gampo is credited with sending scholars to India to develop a Tibetan script and grammar based on Sanskrit, and with making Tibet open to the practice of Buddhism. He secured political alliances with both China and Nepal by marrying princesses from those Buddhist countries. His Chinese wife is said to have had an image of Sakyamuni Buddha, which was installed in the Jokhang temple. The statue, known as Jowo Rinpoche, continues to be revered as the most sacred image in Tibet and the Jokhang, the most sacred temple.

From these beginnings, Buddhism took hold of the Tibetan spirit and was thoroughly established in the Tibetan court during the reign of King Trisong Detsen (c. 740-798), although not without the opposition of those who still held to earlier indigenous forms of religion. under Trisong Detsen, the great Indian Buddhist scholar Santa-raksita and the great Tantric yogi Padmasambhava were invited to Tibet. Santaraksita’s first visit coincided with climatic upheavals such as storms and floods, which were interpreted by Trisong Detsen’s antagonists as the displeasure of the local spirits. In order to overcome this obstacle, he suggested that the king invite Padmasambhava, who was known for his magical arts. Through Tantric rituals and magic formulas, the opposing spirits of Tibet were subdued and bound to the service of the Buddha Dharma by Padmasambhava, known in Tibet as Guru Rinpoche.

Once the way was clear, Santaraksita returned and along with Padmasambhava oversaw the eventual construction of the first monastery of Tibet, Samye. Thus began the Tibetan monastic system and an extensive program of translation of Buddhist texts. During the establishment of Buddhism in Tibet, Buddhist teachers from both India and China were attracted to the region, where they promoted rival schools of thought. The Chinese approach to enlightenment proposed that it was a state achieved instantaneously when physical and mental processes fell away. Alternatively, the Indian teachers proposed that enlightenment was the result of a gradual process of mental purification, and the step-by-step accumulation of merit and wisdom. A famous debate called for by King Trisong Detsen between "sudden" and "gradual" enlightenment was held in 792 at Samye between the Chinese Chan monk Hua Shang and Santarak-sita’s student, Kamalasila. Kamalasila was declared the winner and the indian gradual method of training was accepted as the standard of Buddhism for Tibet.

By the time of the third religious king, Rel-bachen (r. 815-836), Buddhism was strongly supported by the ruling and educated classes of Tibetan society and was on its way to becoming the religion of the people. Relbachen is portrayed as a somewhat fanatic follower of Buddhism. Monks in his reign were known as "Priests of the King’s Head," a reference to the practice of tying a string to his braided hair, to which was attached a cloth that the monks sat on during state ceremonies, signifying the king’s subservience to the sangha. Opposition to the excesses of Relbachen’s rule increased until he was assassinated and succeeded by his elder brother, Lang Darma, a bitter opponent of Buddhism. Lang Darma’s reign ushers in a period of Buddhist persecution and marks the end of what is called the "first dissemination" of Buddhism in Tibet. His assassination in 842 ended the Yarlung dynasty and Tibet entered upon a period of political chaos.

The renaissance of Buddhism in Tibet, known as the "second dissemination," began in about 978 with the arrival of some Indian scholars. In 1042 the famous Indian scholar Atisa founded the first school of Buddhism in Tibet, the Kad-ampa order. The main schools founded after this time, the Gelug, the Kargyu, and the Sakya, are referred to as "new schools" to distinguish them from the Nyingma, the "old school," which traces its origins to Padmasambhava and relies on texts and translations from the period of the first dissemination.

By the 12th century, Tibetan military power had long since waned in the region and the Mongolians with Genghis Khan at their head were the new power in Central Asia. The Mongolians moved to take control of Tibet, but the khan was converted to Buddhism and a "patron-priest" relationship developed between the Sakya chief priest and the ruling khan in which the Sakya lama became the spiritual adviser of the khan and the khan provided the military support for the priest’s interests. In subsequent centuries, the dominance of the Sakya school in the Tibetan monastic system declined and was replaced by the Gelug, founded in 1409 by Tsong Khapa. The Gelug system, anchored by the largest monasteries in Tibet—Gaden, Drepung, and Sera—became a spiritual powerhouse led by the institution of the Dalai Lama, the supreme spiritual and political ruler of Tibet.

The institution of the Dalai Lamas started in 1578 when Sonam Gyatso, the head of the Gelug order, visited the Altan Khan, the most prominent of the Mongol chieftains at that time. In return for his religious instruction, the khan bestowed the title of Dalai, "Ocean" (of Wisdom), on his teacher. From that time on, the successors of Sonam Gyatso as well as his two predecessors bore the title Dalai Lama. in the history of the Dalai Lamas, Ngawang Losang Gyatso, known as the "Great Fifth" (1617-82), is credited with being the first to rule over a united Tibet since the end of the Yarlung dynasty in the ninth century.

Currently Dalai Lama XIV, Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th in this line, presides over the most dramatic upheaval in modern Tibetan history, the advance of Chinese armies into Tibet that began in 1950. In 1959 the Dalai Lama escaped to India, where he was given asylum and allowed to set up a Tibetan government in exile in Dharamsala. He was followed into exile by thousands of Tibetans who made the dangerous trek on foot across the mountains into India. The Chinese Cultural Revolution of the 1960s was particularly hard on Tibet, where there were large-scale destruction of monasteries and suffering of thousands of monastics and lay people. Despite some continued human rights abuses reported by agencies such as Amnesty International, the 14th Dalai Lama has maintained his efforts to seek a political compromise with the Chinese government. in the meantime, economic development in recent years has dramatically transformed Tibetan life.