Aryadeva

(second century c.e.) student of Nagarjuna and Chan patriarch

Aryadeva, also called Kanadeva (god of a single eye), was a follower of Nagarjuna, the great early Mahayana philosopher. He is considered the 15 th patriarch in the Chan (Zen) lineage. He was killed after a debate against brahmanist teachers—that is, teachers representing rival Hindu beliefs. Aryadeva wrote several key texts in the Madhyamika tradition, including Aksarasataka (One hundred verse treatise). This work, along with two others by Nagarjuna, in turn became the core works of the later San Lun (Japanese Sanron) school.

Asanga

(fourth century c.e.) one of the great founders of Yogacara thought and a key Mahayana writer

Asanga converted from an early school of Buddhism to Mahayana and eventually succeeded in persuading his younger brother, Vasubhandu, to convert as well. one version relates how he visited Tusita heaven and was taught the Mahayana doctrine on nonessence by Maitreya, the Buddha of the future. In another version he received his understanding of Mahayana from his earthly teacher, who was named Maitreya. The two brothers founded the Yogacara school of Mahayana Buddhism, which gave preeminence in its teachings to the nature of mind. Asanga wrote the Yogacarabhumi Sastra, the Mahayana-samgraha, and the Abhidharma-samuccaya.

Asita

prophet who forecast the Buddha’s greatness

Asita was a wise man of Kapilavastu, the capital of Sakya, the state in which the historical Buddha was born. After the son’s birth his father, Shuddhodana, requested that Asita study the newborn’s physical features. Asita recognized the 30 marks of a great person and forecast that Sid-dhartha would become either a great leader or, if he renounced the world, a Buddha.

Asoka (Ashoka)

(c. 304-232 b.c.e.) greatest Buddhist monarch and proponent of early Buddhism

Asoka unified much of what is modern India but was shocked in 262 b.c.e. at the suffering he had caused in conquering the rebellious state of Kalinga (roughly corresponding to the modern state of Orissa). The horror of the war was so great that whereas earlier he had had a nominal commitment to Buddhism, it now became active in his life. He vowed to apply Buddhist principles to his rule. This vow included performing numerous good works such as building hospitals for people and animals, digging wells, and setting up travel facilities. Asoka played a crucial part in spreading Buddhism throughout India and abroad. He probably built the first major Buddhist monuments. In Buddhist lore he is said to have overseen the third Buddhist Council at Pataliputra. He ordered the erection of inscribed pillars to commemorate the establishment of the Buddha’s Dharma, or rule, in his lands. He introduced Buddhism to Sri Lanka through his son, Mahinda, and additionally sent his daughter, Sanghamitta, there with a cutting from the Bodhi tree to plant.

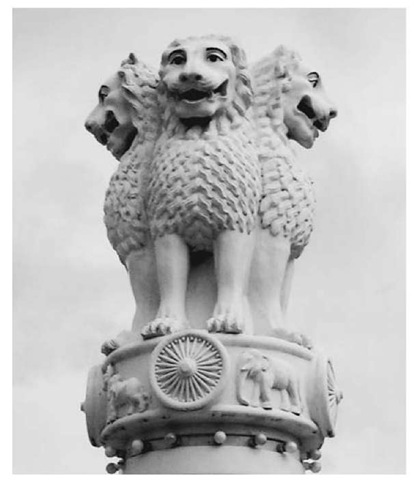

Three lions, the symbol of Emperor Asoka, atop a pedestal at the Kyauktawgyi Paya temple, Mandalay, northern Myanmar (Burma), which re-creates the Emperor Asoka’s pedestals and stone edicts erected throughout India

Though he is now one of the best known of Buddhist figures, many of the details of King Asoka’s life are unknown and much that is known, such as his date of birth, is disputed by scholars. He was born about 304 b.c.e. He was the grandson of Chandragupta, founder of the Mauryan dynasty, and followed his father, Bindusara, to the throne. As king of Magadha he also held the title Devanampiya Piyadasi (Beloved-of-the-gods, he who looks on with affection.)

Asoka died in 232 b.c.e., in the 38th year of his reign. Asoka has since come to represent an ideal of close interaction between temporal ruler and Buddhist principles. He is the cakravartin, the ideal ruler, who causes the wheel of the law—the Buddha’s Dharma—to turn.

Although he was a fabled king, little was known of Asoka from the time Buddhism was stamped out in India until the survey of Indian literature made by European scholars in the 19th century. In several books they found repeated references to a ruthless prince who rose to power over the bodies of his own brothers but who had a sudden conversion to Buddhism, after which he ruled justly and assisted the spread of Buddhism. Later in the century they began to associate the king Asoka in the literature with the King Piyadasi mentioned in the texts of edicts that had been carved into many stone monuments. Finally in 1915, a stone monument with the name Asoka was discovered. Incidentally, Asoka’s edicts comprise the earliest decipherable corpus of written documents from India. They survived because they are written on rocks and stone pillars.

Association of Nuns and Laywomen of Cambodia

This association was established as a nongovernmental institution in 1995 to give voice to a group relatively marginalized in Cambodian Buddhism—unordained nuns, called donchee in the Khmer (Cambodian) language. one goal of the association is to improve the status of nuns in Cambodian society. As in Thailand, Cambodian nuns who may have taken the 10-fold precepts for nuns are nevertheless not allowed to become novices (samaneri) or fully ordained bhiksuni (female monks). in fact women were not ordained anywhere in Southeast Asia for over 1,000 years, following the collapse of the lineages of nuns in Sri Lanka and Burma. Much of the male sangha in Thailand and Cambodia today continues to resist allowing female ordination.

The founding group consisted of 107 women. Membership is open to Buddhist women only. There are today over 10,000 members, 65 percent of whom are nuns. The two Supreme Patriarchs of Cambodian Buddhism are patrons, and the queen, Queen Norodom Monineath Sihanouk, is sponsor. The Association of Nuns and Laywomen of Cambodia (ANLWC) is now found in all provinces throughout the country. it sponsors leadership and social work training for women. This program highlights one of the newest roles of nuns in Cambodian life, serving as social workers and family counselors. The ANLWC receives support from the Heinrich Boll Foundation in Germany.

Association Zen Internationale

The Association Zen Internationale, founded in Paris in 1970, has become the largest Zen Buddhist group in Europe. it was founded by Taisen Deshimaru Roshi (1914-82). The association’s mission is to propagate Soto Zen as presented by Master Deshimaru.

Deshimaru Roshi grew up in an old samurai family. His mother was a follower of Shin Buddhism, and as a youth he was attracted to Christianity. He eventually found his way to Zen, traditionally associated with the samurai.

Deshimaru chose Kodo Sawaki Roshi (d. 1965), a Soto Zen master, as his teacher. He began studying with Kodo Sawaki in the 1930s and remained with him except when serving in the army during World War ii. A married man with a family, Deshimaru did not become ordained as a monk until the time of his being commissioned to take Zen to the West just shortly before Sawaki’s death in 1965.

Leaving his family in the care of his eldest son, Deshimaru moved to France in 1967. He entered without any resources or knowledge of French. From a primitive sitting space to do zazen , he gathered a few followers and built an initial dojo. He founded an association in 1970 and through the 12 remaining years of his life attracted students from across Europe. He eventually received dharma transmission from Master Yamada Reirin, head of Eihei Temple in Japan and was named kaikyosokan (head of Japanese Soto Zen for a particular country or continent) for all Europe.

In the late 1970s the association acquired an estate, La Gendronniere, where Deshimaru oversaw the construction of a temple in 1979 and then a new large dojo that could hold up to 400 practitioners. From there he trained and sent his students out to found centers across Europe. After his death, the association continued under the guidance of senior students.

As of 2005, the association oversaw some 200 dojos and practice centers, most in Europe. In1983, a senior student, Robert Livingston Roshi, founded the first center in North America, in New Orleans, Louisiana. Association-related centers are now located in 36 countries.

Asubha

Asubha, or ugliness, is a concept used in a standard Buddhist meditation practice in which the cultivator focuses on 10 "disgusting objects," including the body and its decay. To do this the meditator is advised to spend time observing decaying corpses in a burial ground. This list of 10 objects is part of the larger list of 40 subjects given in the Visud-himagga, the standard text on Buddhist meditation written by Buddhaghosa, c. 400 c.e.

Why do Buddhist texts encourage mediation on ugliness? The underlying idea is to reinforce the idea of decay and impermanence. All phenomena decay and change, a key idea in Buddhist practice and teachings.

Asvaghosa

(second century c.e.) Mahayana writer and poet

Asvaghosa propagated Buddhism through his art in the second century c.e. Asvaghosa at first worked against Buddhism but later became a fervent champion. His Budhacharita, the story of the Buddha’s life, is a key work of Indian literature. Asvaghosa in general put definite emphasis on the forest-dwelling aspect of the Buddha’s life, as opposed to depicting the Buddha as an urban individual, as is the general tendency in the Vinaya, the part of the Buddhist canon that details rules for the monkhood. Asvaghosa is most remembered for his Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana (Mahayana-sraddhotpada-sastra). Some scholars contend this work, while attributed to Asvaghosa, was produced by later Chinese writers. Regardless, we may consider Asvaghosa to be the first major scholar of Mahayana.

Atisa

(11th century) Indian Buddhist teacher instrumental in introduction of Buddhism to Tibet Atisa was the key person in the second transmission of Buddhism to Tibet. During the ninth century, the Tibetan king, Langdarma, had persecuted Buddhism and instigated a period of decline. Then in the next century several of the rulers in western Tibet sent Tibetans to India to recover the tradition. of 21 who were sent, two returned in 978—Rinchen Zangpo and Lekpe Sherab—and they began the process of revival with new translations of Buddhist texts. The older texts being used by the Nyingma practitioners were examined and anything not confirmed to have originated in India deleted. Thus, the attempt was made to exclude from the teachings any pre-Buddhist teachings from Tibetan religions.

Then in the 11th century, Lkhalama Yeshe-o, the king of western Tibet, invited the Indian teacher Atisa, a scholar from Vikramashila University in Bengal, to his land. While details of his life are few, he was the author of the Bodhipathapradipa (Lamp for the path of enlightenment), his summary of Tantric Buddhist teachings, which presents its material in such a way that the believer may appropriate Buddhist teachings and enlightenment along a graded path of attainment. He would spend his life in the revival of a reformed Buddhism.

Atisa took with him a disciple, Dromtonpa, who established Rva-sgreng monastery in 1056, generally considered the date of the founding of the Kadampa school of Tibetan Buddhism. That tradition would eventually be absorbed into the Gelug school headed by the Dalai Lama.

Aum Shinrikyo/Aleph

Because of the homicidal actions perpetrated by its leadership, Aum Shinrikyo, one of the late-20th-century new religions of Japan, has attained a pariah status in Buddhist circles generally. The aura of evil that surrounds it has made analysis difficult—no group, and rightfully so, wants to be connected with it.

Aum Shinrikyo was founded by Shoko Asa-hara, born Chizuo Matsumoto in 1955. After failing the entrance examination to Tokyo University, Asahara began studying Chinese medicine. He also joined Agon Shu, a new Buddhist religion based on the Agama sutras and efforts to remove one’s inherited karma through ritual activity. In 1984, Asahara began holding yoga classes, through which he gained his first followers. Through the mid-1980s he visited india and attained enlightenment while absorbing some elements of Tibetan Buddhism.

Upon his return to Japan, his following evolved into the Aum Shinrikyo, the "teaching of the supreme truth." Aum is a basic mantra recited in India, the creative word by which the world came into being. After overcoming some complaints from the families of members, the group was registered with the government in 1989.

Aum Shinrikyo spread through Japan and established a rural headquarters complex near Mt. Fuji. It also continued to generate public controversy. Parents who disapproved of the group, and especially the way in which some members severed standard communications with their families after joining, persisted in attacking the group. The families hired a lawyer, Sakamoto Tsutsumi, to pursue their concerns. Sakamoto began aggressively and effectively to attack the group. Then in November 1989, Sakamoto, his wife, and his infant son suddenly disappeared. Foul play was alleged, but there was no evidence.

Meanwhile, Asahara had been absorbing elements of Western apocalyptic thinking, primarily from his reading of the Christian New Testament, with an emphasis on the Book of Revelation, and the prophetic writings of Nostradamus. He also urged the group to follow the example of the Soka Gakkai and become involved in running candidates for public office. With considerably less following and no political skills, the Aum Shinrikyo candidates lost in an embarrassing defeat.

During the early 1990s, two different Aum realities developed. Outwardly, and to most members, Aum presented a program that invited individuals to seek enlightenment through an eclectic program of spiritual exercises derived from Agon Shu, Tibetan Buddhism, modern technology in altered consciousness, and the fertile imagination of Asahara. in this endeavor a number of books were published including the group’s primary text, AUM Supreme Initiation (1988).

At the same time, an increasingly apocalyptic view of current events and the near future developed. As the tension with the public increased, the vision of the future increasingly pictured Aum Shinrikyo as an active force in bringing about those events. The apocalypticism increasingly took center stage in the core leadership group, though it is hard to know how much the ideology seeped to the larger membership. However, one important change within the group was the 1994 reorganization of the leadership structure to mirror the organization of the Japanese government, presumably to facilitate Aum’s assuming power after the coming catastrophic events.

At the same time that Aum’s ideology was transforming, within the top leadership strategies were discussed on blocking various official attacks on the group. As would later become known, some leaders had planned the death of Sakamoto Tsutsumi and his family, in 1989. In 1993, the group began to manufacture nerve gas, initially produced before the year was out. The gas was initially used in 1994 in Matsumoto, Japan, in an attempt to prevent some legal proceeding against Aum by injuring the judges. The relative success of the event prepared the way for the March 20, 1995, event in which the nerve gas was released at the Kasumigaseki Station in central Tokyo, which also happened to be near a number of government offices and the headquarters of the National Police Agency. Twelve people died and hundreds more were injured more or less severely.

This incident, more than any other, served to focus attention on Aum, which immediately rose to the top of the suspect list. Raids on Aum centers, including the main center near Mt. Fuji, followed and arrests were made. The volatile nature of the nerve gas agent used made analysis and hence evidence gathering difficult. However, in September, a major break occurred when a member involved in the disposal of the bodies of the Sakamoto family confessed and led police to the bodies.

Asahara, who had been in hiding in a secret room at the headquarters, was finally arrested along with most of the leadership and several hundred people deemed to have been involved in planning and executing the several incidents or in assisting and/or protecting the leaders in the weeks after the March gassing incident.

Over the next several years, the Japanese authorities worked slowly and methodically to build a case against Asahara and his major lieutenants. The case made through the trials and testimonies of those involved on the periphery of the crimes eventually led to the trial and conviction of the major perpetrators, including Asahara. Upon conviction, the leaders were sentenced either to death or to lengthy prison terms.

Meanwhile, attempts were made to disband the organization, which, in a greatly weakened state, had been held together by those few leaders not indicted in the gassing incident. As the great majority of the members were not involved in any illegal or violent activities, Aum was allowed to remain in existence. The continuing leadership made several public apologies for the actions of their colleagues and promised to show their regret by paying a large sum to the victims and their families. The group also changed its name to Aleph, under which it continues. The small group, of several thousand members, continues to be heavily monitored by the police.

Australia, Buddhism in

Buddhism is an increasingly important religious presence in Australia. Buddhists first arrived in 1848 when some transient Chinese workers immigrated to work on the Victorian gold fields.

However, a permanent Buddhist community did not emerge until 1876, when Sri Lankans settled on Thursday Island, off the northern tip of Queensland, to work the sugarcane plantations. By the end of the decade they would be joined by a number of Japanese, who scattered across the northern coast to work in the gathering of pearls. Japanese immigration was stopped by the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901, part of a broad policy to maintain dominance of people of European descent. Through the next generations, Buddhism remained the faith of several shrinking ethnic communities. The community on Thursday Island eventually died out, and the temple site was replaced in later years by a post office. All that survives of the original community are two Bodhi trees, descendents of the tree under which Gautama Buddha found enlightenment.

The first Western Buddhist group, the Little Circle of the Dharma, emerged in Melbourne in 1925, but it was a community only until after World War II. Then in 1951, Sister Dhammadinna, an American-born Buddhist nun visiting Australia, prepared to spread the Theravada teaching she had acquired in Sri Lanka over the previous three decades. Her visit resulted in the formation of the Buddhist Society of New South Wales under the leadership of Leo Berkley, a Dutch-born businessman and resident of Sydney. Today the society is the oldest existing Buddhist group in Australia. it nurtured the growth of similar groups in other cities, which were united in the Buddhist Federation of Australia in 1958.

In 1971, Somaloka, a monk from Sri Lanka, traveled to Sydney at the request of the Buddhist Society of New South Wales. He opened a monastery and retreat center in the Blue Mountains west of the city. This effort signaled a new era of growth for Australian Buddhism. That growth was built upon by both the immigration of people from different nearby countries that are predominantly Buddhist as well as the conversion of native Australians to the faith. Growth among the latter segment was spurred by the early visits of the Dalai Lama in 1982, 1992, and 1996. By the time of his third visit, the Buddhist community claimed almost 200,000 residents, of whom some 30,000 were native Australians and the rest largely first-generation immigrants. Taiwanese members of Foguangshan have opened a temple complex at Wollongong, Nan Tien, which rivals its headquarters complex in Taiwan.

The rapid growth of Buddhism created a situation in the mid-1980s in which many diverse Buddhist centers carried on their programs oblivious to other nearby groups. This situation led officials from the World Fellowship of Buddhists to go to Australia to promote the fellowship’s goals of cooperation and coordination. In 1984, for example, Teh Thean Choo, an executive with the fellowship, traveled to Sydney and became the catalyst for the formation of the Sydney Regional Buddhist Council, which evolved into the Buddhist Council of New South Wales. Similar regional structures now draw the Western and Eastern ethnic Buddhists together on a regular basis.

The single largest segment of Australian Buddhism is found in the Vietnamese community. The unified Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation of Australia-New Zealand, founded in 1980, now claims some 100,000 lay practitioners, about one-fourth of the entire Australian Buddhist community. it is the only association of centers with temples in each of Australia’s states. Significant other ethnic Buddhist communities are found among the Burmese, Laotians, Thai, Cambodians, Sri Lankans, Koreans, Tibetans, and Chinese (including Chinese from Taiwan, Malaysia, and Singapore).

Avalokitesvara

Avalokitesvara (He who gazes) is the Sanskrit name for Guan Yin (Kuan Yin, Japanese Kan-non, Tibetan spyan-ras-gzigs). Avalokitesvara was a major Mahayana bodhisattva figure in such sacred Buddhist texts as the Lotus Sutra. In India and Tibet, Avalokitesvara is pictured as a male. In China and other East Asian cultures Avalokitesvara has assumed female form, as Guan Yin. Avalokitesvara also became important as a Tantric deity, especially in Tibet. The bodhisattva is often shown with many heads (11) and multiple arms (four, six, or, often, 1,000).

What explains the importance of Avalokites-vara in most Buddhist cultures? This figure is most closely associated with karuna, "compassion," a key value in Mahayana Buddhism, as well as Tantric forms of Buddhist practice. The urge to personify this key value helps us understand the popularity of images of Avalokitesvara, and especially Guan Yin/Kannon.