Intrauterine devices (IUDs) have a long history. Most of the early devices, however, were not technically designed for contraceptive use but rather as pessaries to be placed in the vagina with a stem extending through the cervical opening into the uterus. Although nominally inserted to correct uterine positions (prolapse or other difficulties), they also induced abortions as well as prevented pregnancies. In the United States, where technically contraceptive devices could not be patented, pessaries could, and in the last part of the nineteenth century many pessaries were widely advertised and clearly were used as a means of contraception.

Robert Latou Dickinson promoted IUDs as a contraceptive device in the United States as early as 1916. The devices were widely discussed at the Fifth International Conference on Birth Control in 1922, in part because of the efforts of Ernst Grafenburg, who began experimenting with various types of IUDs in 1909, although he did not begin publishing on the topic until the 1920s and 1930s. Grafenburg developed a ring of gut and silver wire that became popular in Germany in the 1920s. One of the feared problems with such inserts and the one that delayed their widespread use was the problem of infection. It was only after the discovery of antibiotics, from the 1940s onward, that a pelvic infection that might result could be dealt with easily. Earlier such an infection might well have become fatal.

Still, there was experimentation. In 1930, Tenrei Ota of Japan introduced gold and gold-plated silver intrauterine rings, which he claimed were both more effective and less prone to transmit infection than the Grafenburg device. Both inserts were used but after a period of initial enthusiasm both quickly ran into difficulty. The Japanese government for a time even prohibited the use of Ota’s device, whereas Grafenburg abandoned his ring because of opposition of European physicians. It, however, continued to be used in Israel.

In the post—World War II era, encouraged by the development of the new antibiotics, more physicians began to experiment with IUDs. The major turning point occurred at an international conference on IUDs held in New York City in 1962 under the auspices of the Population Council. Physicians from the United States, Israel, Germany, and elsewhere reported on their favorable experiences with IUDs. Equally important as the ability to control infection in encouraging the use of IUDs was the development of polyethylene, a biologically inert plastic that could be molded into any desired configuration. It was flexible (thus easily inserted into the uterus) and could spring back after insertion to its predetermined shape.

One of the key figures in the development of a safe, functional IUD and in bringing about an attitude change regarding its use was Jack Lippes, a gynecologist from Buffalo, New York. Influenced by the reports of the successful use of IUDs (19,000 using the Ota ring in Japan and 866 using the Grafenberg ring in Israel), Lippes inserted the Grafenberg ring—made from silkworm gut—on twenty of his patients. Lippes soon ran into problems, primarily when trying to remove the device, because it lacked a tail and required him to use an instrument similar to a crochet hook for retrieval. This worried him because in the process it might also scratch the lining of the uterus, increasing the risk of infection. Lippes experimented with the Ota ring as well and to aid in its removal he attached a string that dangled through the cervix. Although this facilitated removal, in about 20 percent of his cases the Ota ring would rotate, winding the string up into the uterine cavity.

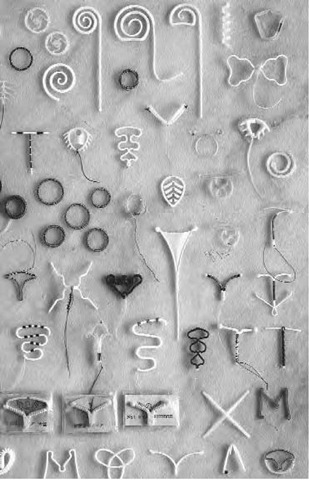

A display of intrauterine devices at the Museum of Contraception in Toronto, Ontario, Canada

As he continued his experiments, Lippes turned to polyethylene that he formed into a double loop with a monofilament thread of the same material hanging from it. Initially this caused some problems because the thread was difficult to see in the vagina, but after dying the thread blue he found he could see it and thus easily remove the IUD. The existence of the blue thread also allowed women to check that the device was still in place. Though there were other competitors such as the Margulies Spiral and the Binberg Bows, the Lippes Loop became the best known and most widely used device in developing countries outside of China. The loops were available in four types from the smallest, A, to the largest, D, and they served as a standard for evaluating other IUDs.

How IUDs Work

Originally, it was difficult to explain why IUDs prevented pregnancy. Animal studies were not as helpful as they could have been because the way IUDs prevented pregnancy varied from species to species. In sheep and chicken, they blocked sperm transport; in the guinea pig, rabbit, cow, and ewe, they interfered with the function of the corpus luteum (the yellow egg sac in the ovary that secretes progesterone). Obviously several things appeared to be happening at the same time. Ultimately research demonstrated that the IUDs had an effect on both ova and sperm in a variety of ways. The IUD stimulates a foreign body inflammatory reaction in the uterus, not unlike the reaction experienced with a splinter in the finger. The concentration of white blood cells, prostaglandins, and enzymes that collect in response to the foreign body then interferes with the transport of sperm through the uterus and fallopian tubes and damages the sperm and ova, thus making fertilization impossible.

Problems

Unfortunately, not all the IUDs marketed in the 1960s and 1970s were tested as thoroughly as the Lippes Loop. As drug companies tried to compete with each other, they often did not test the product themselves. A problem arose over the Dalkon Shield, a poorly designed, relatively untested device that was rushed onto the market by a major pharmaceutical firm, the A. H. Robins Company, to capture a share of the growing IUD market. Robins purchased the right to the Dalkon Shield, developed by Hugh Davis and his business associates in the 1970s. In rushing the Dalkon Shield to the market, Robins relied upon reports by Davis and his colleagues. Apparently most of these were not particularly accurate and were in violation of professional ethics because Davis was doing both the testing and the marketing. Though questions were raised about the Dalkon Shield almost as soon as it appeared on the market—insertion was particularly painful and there was a high rate of infection—complaints were initially ignored by Davis and his associates as well as by Robins. By 1976, seventeen deaths had been linked to its use, but Robins took no action until 1980, when it finally advised physicians to remove the shield from women who were still wearing it. The company’s failure to act resulted in a large number of lawsuits, which ultimately led to Robins declaring bankruptcy.

In the aftermath of the Robins failure, other companies marketing IUDs were also sued, and although the lawsuits were not particularly successful, the liability insurance rates had risen so much that all companies in the United States ceased to distribute any IUD device for a time. The devices, however, were available in Canada and most of the rest of the world. A major reason for the difference between the use of IUDs in the United States and the rest of the world is that the United States is practically alone among the countries of the world in relying almost totally on private enterprise for its pharmaceuticals even though much of the research is paid for by the government. Obviously, private pharmaceutical companies want to sell IUDs for a profit. Because only a small percentage of American women used the device—approximately seven percent in 1982—1983—and because IUDs are long lasting, profits from any IUD after the initial adoption were modest. The Lippes IUD, for example, cost only a few pennies to manufacture, and though it required the services of a physician to insert, few drug companies would gain any profit from selling it, and it simply ceased to be distributed in the United States. One good effect of the Dalkon Shield episode, however, was that it led the U.S. government to finally establish standards for IUDs. Because they originally had been regarded as devices rather than drugs, they required no prior approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but they now do.

A second generation of IUDs—however, now with FDA approval—appeared on the market and the medicated ones promised a somewhat higher return to the drug manufacturers. Some of these released copper, other released steroids into the uterine cavity, having the same effect as the birth control pill. The copper devices had considerable advantages over the Lippes Loop because the copper devices are less likely to be expelled, produce less menstrual blood loss, are better tolerated by women who have not yet delivered babies, are more likely to stay in place after postpartum or postabortion insertion, and are slightly more effective.They originally needed to be replaced more often and cost more, hence allowing for more profit for the maker, but the newer ones such as the Copper T 308 has less than a 2 percent failure rate in the first year of use and is almost 100 percent effective after that for up to ten years. It is one of the most effective contraceptives ever developed. Interestingly it was approved for sale by the FDA in 1984 but it took several years before a company, Gyno Pharma, Inc., was willing to market it in the United States because of the Dalkon Shield incident.

The steroid-releasing IUDs release either progesterone or synthetic hormones called pro-gestins into the uterus. The effective doses of steroids released from IUDs are substantially lower than doses required for oral administration, and the systemic side effects are less frequent. First on the market was Progestasert, which has a reservoir containing 38 mg of pro-gestin, released at a rate that requires its replacement after one year. There is a longer-lasting IUD that releases 20 mg of levon-orgestrel per day and has a reservoir holding up to a five-year supply. Others will undoubtedly appear on the market. Interestingly, the Lippes Loop is still widely used in many of the developing countries of the world.

Early studies indicated that an IUD increased the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), an infection of the upper genital tract that can cause infertility. Later studies indicated that the risk was usually limited to the first four months after IUD insertion and to those women who have been exposed to a sexually transmitted disease. The levonorgestrel IUD seems to be particularly effective against PID. There are contraindications, however. For example, a copper IUD should not be inserted into a woman who has a copper allergy or Wilson’s disease (a rare inherited disorder of copper excretion). Women who fall into any of the following risk categories should not use the IUD: those who are pregnant or have had PID, those with a history of ectopic pregnancy, those with gynecological bleeding disorders, women in whom there is a suspected malignancy of the genital tract or a congenital uterus abnormality, or women with fibroids that prevent proper IUD insertion. Insertion of an IUD in the initial stage of a pregnancy will cause the fetus to abort. Women who have passed the menopause should have their IUDs removed because narrowing and shrinking of the uterus may make later removal difficult and increase the chances of infection. The user should also periodically check for the IUD string and return for follow-up care if she cannot locate the string or if she misses a period.

The IUD, in summary, is a particularly good choice for a parous woman (one who has been pregnant and delivered at least once) who does not want to be bothered with taking pills daily. In some women who have never been pregnant, an IUD increases the menstrual flow, causes pain, and irritates the cervix, thus making it a less desirable choice. The absence of the IUD from the U.S. market for several years was a result of panic on the part of the drug companies when the A. H. Robins Company was sued by so many people. The other IUDs were never banned by the FDA and the current devices on the market are safe and effective.