A son of a solicitor’s clerk, Charles Bradlaugh attended schools in London until he was eleven, when he went to work in his father’s office. After that he had a mixture of jobs but spent most of his spare time attending open air meetings in London parks listening to the open discussion of social, political, and theological questions. On Sundays he taught Sunday school but as he was being prepared for confirmation, he began to express some of his doubts about the 39 Articles of the Church of England, and when he expressed these, the minister denounced him to his parents as atheistic and suspended him from Sunday school. The minister did not stop there, but also convinced his employer to fire Brad-laugh unless he changed his opinions. Bradlaugh found shelter with the widow of Richard Carlile and tried to support himself by selling coal, all the time spending his time trying to learn Greek and Hebrew. Unable to support himself and in debt, he joined the army, where he served for three years before a legacy from a great aunt enabled him to buy his way out of the army.

Bradlaugh gained fame and popularity as a powerful and pugnacious lecturer, debater, and pamphleteer, always seeming to hunt for causes that he believed would help the worker. He began publishing a newspaper, the National Reformer (1869—1893), but refused to deposit the required 800 pounds in sureties against blasphemous or seditious libel. When ordered to stop publishing, he took the matter to court, won his case, and saw the statute repealed. Often his efforts in court were stymied because judges refused to hear freethinkers (read “atheists”), but Bradlaugh continued to fight until they did so. He stood for Parliament in 1868, even though, as an avowed atheist, he knew he would not be allowed to sit there. Defeated in the original election, he continued to run at every opportunity until in 1880 he was elected. When the House of Commons refused to seat him because he would not take an oath of loyalty on the Bible, Bradlaugh went to court. The result was a six-year legal action during which he continued to win reelection until in 1886, when a new Speaker allowed him to enter without swearing on the Bible. Bradlaugh continued to serve until his death in 1891.

Among his causes was birth control, and early on he had published articles in the National Reformer by the birth control reformer George Drysdale. Though his coeditor, Joseph Barker, had broken with him on this issue, Bradlaugh declared that he would persist in his advocacy of Malthusian views. He got his chance to do more than publish Drysdale when in 1876 a Bristol bookseller named Henry Cook was sentenced to two years in prison for publishing an edition of Charles Knowlton’s Fruits of Philosophy.

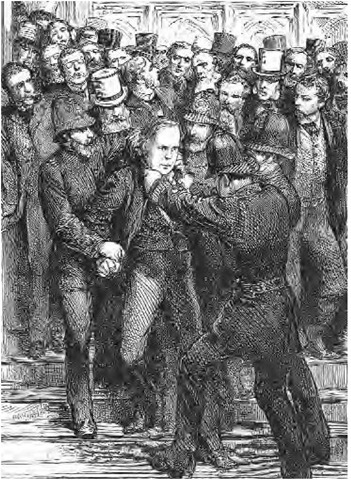

Charles Bradlaugh, a freethinker and member of the British Parliament, was taken to court for selling books containing information about birth control.

As part of a deal with the prosecution to let him off with a suspended sentence and court costs, Watts pleaded guilty to publishing an obscene book. Bradlaugh then severed his connections with Watts,and went on the offensive. Bradlaugh and Annie Besant formed the Free Thought Publishing Company, republished Fruits of Philosophy with medical notes by George Drysdale, and notified the police when he and Besant would appear in public to sell the book in person. Some five hundred copies were sold in the first twenty minutes, after which the two were arrested and a trial was held. Found guilty in 1877, they were sentenced to six months’ imprisonment and fined 200 pounds. On appeal the decision was overturned and Brad-laugh, determined to continue publishing, sued the police to get the copies they had confiscated returned. He was successful and sold them with the words “Recovered from the police” stamped in red across the cover.

Though freethinkers had been in the forefront of the activity for birth control, not all agreed with what Bradlaugh was doing. A group of disgruntled freethinkers issued a scurrilous Life of Bradlaugh, in which Bradlaugh was accused, among other things, of advocating prostitution (by publishing Drysdale’s articles), trying to establish a universal female harem, and encouraging homosexuality.

After he won his battle to sit in Parliament, the militant firebrand came to be acknowledged as a respected reformer because most of the things he advocated and did in his life came to be accepted.