Protozoan The simplest forms of animal life, consisting of aquatic single cells or colonies of single cells, such as amoeba and paramecium. The "protists" ingest food and live in both fresh and marine waters as well as inside animals, and most are motile. Estimates of the number of species of protozoa are between 12,000 to 19,000 species. Many protozoans are known to cause human disease, such as Giardia lam-blia, a flagellated organism that can infect via water or be contracted via contaminated foods. It causes giar-diasis, the most frequent cause of nonbacterial diarrhea in North America. Cryptosporidium parvum has a strong association between cases of cryptosporidiosis and immunodeficient individuals (such as those with AIDS). Cyclospora cayetanensis infection results in a disease with nonspecific symptoms: usually one day of malaise, low fever, diarrhea, fatigue, vomiting, and weight loss. Cryptosporidium parvum causes intestinal, tracheal, or pulmonary cryptosporidiosis. Acan-thamoeba spp., Naegleria fowleri, and other amoebae are responsible for primary amoebic meningoen-cephalitis (PAM). Naegleria fowleri is associated with granulomatious amoebic encephalitis (GAE), acan-thamoebic keratitis, and acanthamoebic uveitis. Entamoeba histolytica causes amoebiasis (or amebiasis), resulting in various gastrointestinal upsets, including colitis and diarrhea. In more severe cases, the gastrointestinal tract hemorrhages, resulting in dysentery.

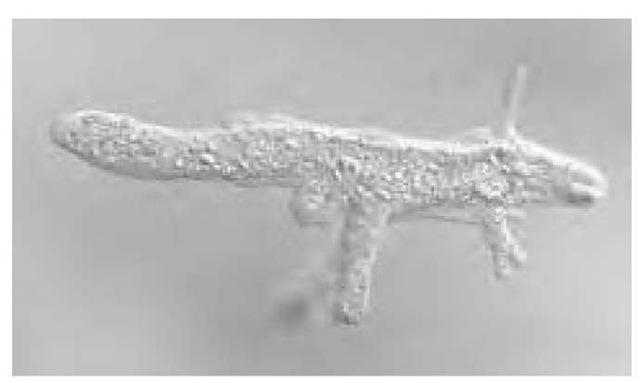

Amoebas are protozoans, which are the simplest form of animal life.

The Vorticella is a protist (protozoan) and belongs to the phyllum Ciliophora. A protist that turns as it moves.

Other protozoans such as Naegleria fowleri cause meningitis; Trypanosoma cruzi causes African sleeping sickness and Chagas disease; and Plasmodium spp. causes malaria.

Provirus Term given to a retrovirus DNA when it is integrated into the infected host cell genome. It can remain inactive for periods of time and can be passed to each of the infected cell’s daughter cells.

Proximate causation Explains how organisms respond to their immediate environment (through behavior, physiology, and other methods) and the mechanics of those responses.

Pseudocoelomate Any invertebrate whose body cavity is not completely lined with mesoderm. The embryonic blastocoel persists as a body cavity and is not lined with mesodermal peritoneum (the lining of the coelom); therefore it is called a pseudocoel ("false cavity"). Examples include nematodes, rotifers, acantho-cephalans, kinorhynchs, and nematomorphs.

Pseudopodium A dynamic protruding structure of the plasma membrane used by amoeboid-type cells used for locomotion and phagocytosis.

Punctuated equilibrium A part of evolutionary theory that states that evolution works by alternating periods of spurts of rapid change followed by long periods of stasis.

Pupa The stage preceding the adult in a holometa-bolous insect, for example, the stage in a butterfly or moth when it is encased in a chrysalis and undergoing metamorphosis.

Quadruped An animal that moves using four-footed locomotion; moves using all four limbs.

Quantitative character (polygenic character; polygenic inheritance) An inherited character or feature in a population whose phenotypes have continuous variation, such as height or weight, and whose distribution follows small discreet steps and can be numerically measured or evaluated; expressed often from one extreme to another. The effects are due to both environment and the additive effect of two or more genes.

Quantum evolution A rapid increase in the rate of evolution over a short period of time.

Quarantine A way to control or prevent importing, exporting, or transporting of plants, animals, agricultural products, and other items that may be able to spread disease or become a pest.

Quasisocial Refers to a situation where members of the same generation share a nest and care for the brood.

Quaternary period The most recent geologic period of the Cenozoic era. It began 2 million years ago with the growth and movement of Northern Hemisphere continental glaciers and the Ice Age.

Quaternary structure There are four levels of structure found in polypeptides and proteins. The first or primary structure of a polypeptide or protein determines its secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures. The primary structure is the amino acid sequence. This is followed by the secondary structure, how the amino acids adjacent to each other are organized in the structure. The tertiary or third structure is the folded three-dimensional protein structure that allows it to perform its role, and the fourth or quaternary structure is the total protein structure that is made when all the sub-units are in place. Quaternary structure is used to describe proteins composed of multiple subunits or multiple polypeptide molecules, each called a monomer. The arrangement of the monomers in the three-dimensional protein is the quaternary structure. A considerable range of quaternary structure is found in proteins.

Queen A member of the reproductive caste in semiso-cial or eusocial insect species.

Queenright A colony that contains a functional queen. A monogynous colony in which one morphologically different female ant is the only reproducer.

Queen substance A pheromone secreted by queen bees and given to worker bees that controls them from producing more queens.

Quiescent center A region of cells behind the root cap that contains a population of mitotically inactive cells; precedes the organization of a root meristem and contains high levels of the enzyme ascorbic acid oxidase, which may suggest a mechanism that links gene expression with patterning. It is the region in the apical meris-tem that has little activity, and cells rarely divide or do so very slowly. However, cells can be encouraged to divide by wounding of the root. The quiescent center (QC) consists of a small group of cells at the tip called the initials. It is the initials that divide very slowly and create the quiescent center. Cells around the QC divide rapidly and form the majority of the cells of the root body.

Raceme An inflorescence, a flower structure, in which stalked flowers are borne in succession along an elongate axis, with the youngest at the top and oldest at the base.

Racemic Pertaining to a racemate, an equimolar mixture of a pair of enantiomers. It does not exhibit optical activity.

Radial cleavage A form of embryonic development where cleavage planes are either parallel or perpendicular to the vertical axis of the embryo. Found in deuterostomes, which include echinoderms and chor-dates.

Radial symmetry A body shape characterized by equal parts that radiate outward from the center like a pie. Found in cnidarians and echinoderms.

Radiata The animal phylum that includes cnidarians and ctenophores; radially symmetric.

Radiation Released energy that travels through space or substances as particles or electromagnetic waves and includes visible and ultraviolet light, heat, X rays, and cosmic rays. Radiation can be nonionizing (infrared, visible light, ultraviolet, electromagnetic) or ionizing (alpha, beta, gamma, and X rays). Ionizing radiation can have severe effects on human health, but it is also used in medical diagnostic equipment and can be used to provide a host of other economic benefits from electrical power generation to smoke detectors.

Radical A molecular entity possessing one or more unpaired electrons, formerly often called "free radical." A radical can be charged positively (radical cation) or negatively (radical anion). Paramagnetic metal ions are not normally regarded as radicals.

Radicle An embryonic plant root.

Radioactive isotope An isotope is an element with a different amount of neutrons than protons. Isotopes are unstable and spin off energy and particles. There are radioactive and nonradioactive isotopes, and some elements have both, such as carbon. Each radioactive isotope has its own unique half-life, which is the time it takes for half of the parent radioactive element to decay to a daughter product. Some examples of radioactive elements, their stable daughters, and half-lives are: potassium 40-argon 40 (1.25 billion years); rubidium 87-strontium 87 (48.8 billion years); thorium 232-lead 208 (14 billion years); uranium 235-lead 207 (704 million years); uranium 238-lead 206 (4.47 billion years); carbon 14-nitrogen 14 (5,730 years).

Radiocarbon dating By using radioactive isotopes, it is possible to qualitatively measure organic material over a period of time. Radioactive decay transforms an atom of the parent isotope to an atom of a different element (the daughter isotope) and ultimately leads to the formation of stable nuclei from the unstable nuclei. Archeologists and other scientists use radioactive carbon to date organic remains. The radioactive isotope of carbon, known as carbon-14, is produced in the upper atmosphere and absorbed in a known proportion by all plants and animals. once the organism dies, the carbon-14 in it begins to decay at a steady, known rate. Measuring the amount of radiocarbon remaining in an organic sample provides an estimate of its age. The approximate half-life of carbon 14 is 5,730 plus or minus 30 years and is good for dating up to about 23,000 years. The carbon-14 method was developed by the American physicist Willard F. Libby in 1947.

Radiometric dating The use of radioactive isotopes and their half-lives to give absolute dates to rock formations, artifacts, and fossils. Radioactive elements tend to concentrate in human-made artifacts, igneous rocks, the continental crust, and so the technique is not very useful for sedimentary rocks, although in some cases, when certain elements are found, it is possible to date them using this technique. other radiometric dating techniques used are:

Electron Dating Spin Resonance

Electrons become trapped in the crystal lattice of minerals from adjacent radioactive material and alter the magnetic field of the mineral at a known rate. This nondestructive technique is used for dating bone and shell, since exposure to magnetic fields does not destroy the material (e.g., carbonates [calcium] in limestone, coral, egg shells, and teeth).

Fission Track Dating

This technique is used for dating glassy material like obsidian or any artifacts that contain uranium-bearing material, such as natural or human-made glass, ceramics, or stones that were used in hearths for food preparation. Narrow fission tracks from the release of high-energy charged alpha particles burn into the material as a result of the decay of uranium 238 to lead 206 (half-life of 4.47 billion years) or induced by the irradiation of uranium 235 to lead 207 (half-life of 704 million years). The number of tracks is proportional to the time since the material cooled from its original molten condition, i.e., fission tracks are created at a constant rate throughout time, so it is possible to determine the amount of time that has passed since the track accumulation began from the number of tracks present. This technique is good for dates from 20 million to 1 billion years ago. U-238 fission track techniques are from spontaneous fission, and induced-fission tracking from U-235 is a technique involving controlled irradiation of the artifact with thermal neutrons of U-235. Both techniques give a thermal age for the material in question. The spontaneous fission of uranium-238 was first discovered by the Russian scientists K. A. Petrzhak and G. N. Flerov in 1940.

Potassium-Argon Dating

This method has been used to date rocks as old as 4 billion years and is a popular dating technique for archeological material. Potassium-40, with a half-life of 1.3 billion years in volcanic rock, decays into argon-40 and calcium-40 at a known rate. Dates are determined by measuring the amount of argon-40 in a sample. Argon-40 and argon-39 ratios can also be used for dating in the same way. Potassium-argon dating is accurate from 4.3 billion years (the age of the Earth) to about 100,000 years before the present.

Radiocarbon Dating See radiocarbon dating. Thermoluminescence Dating

A technique used for dating ceramics, bricks, sediment layers, burnt flint, lava, and even cave structures like stalactites and stalagmites. It is based on the fact that some materials, when heated, give off a flash of light. The intensity of the light is used to date the specimen and is proportional to the quantity of radiation it has been exposed to and the time span since it was heated. Similar to the electron spin resonance (ESR) technique. Good for dates between 10,000 and 230,000 years.

Radionuclide A radioactive nuclide. The term nuclide implies an atom of specified atomic number and mass number. In the study of biochemical processes, radioactive isotopes are used for labeling compounds that subsequently are used to investigate various aspects of the reactivity or metabolism of proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids or as sources of radiation in imaging. The fate of the radionuclide in reactive products or metabolites is determined by following (counting) the emitted radiation. Prominent among the radionuclides used in biochemical research are : 3H, i4C, 32P, 35Ca, 99mTc, i25I, and "U.

Ragweed (Ambrosia) Ragweed refers to the group of approximately 15 species of weed plants, belonging to the Compositae family. Most ragweed species are native to North America, although they are also found in eastern Europe and the French Rhone valley. The ragweeds are annuals characterized by their rough, hairy stems and mostly lobed or divided leaves. The ragweed flowers are greenish and inconspicuously concealed in small heads on the leaves.

The ragweed species, whose copious pollen is the main cause of seasonal allergic rhinitis (hayfever) in eastern and middle North America, are the common ragweed (A. artemisiifolia) and the great, or giant, ragweed (A. trifida). The common ragweed grows to about 1 meter (3.5 feet), is common all across North America, and is also commonly referred to as Roman wormwood, hogweed, hogbrake, or bitterweed. The giant ragweed, meanwhile, can reach anywhere up to 5 meters (17 feet) in height and is native from Quebec to British Columbia in Canada and southward to Florida, Arkansas, and California in the United States. Due to the fact that ragweeds are annuals, they can be eradicated simply by being mowed before they release their pollen in late summer.

Rain forest An evergreen forest of the tropics distinguished by a continuous, closed canopy of leafy trees of variable height and diverse flora and fauna, with an average rainfall of about 100 inches per year. Rain forests play an important role in the global environment, and destruction of tropical rain forests reduces the amount of carbon dioxide absorbed, causing increases in levels of carbon dioxide and other atmospheric gases. Cutting and burning of tropical forests contributes about 20 percent of the carbon dioxide added to the atmosphere each year. Rain forest destruction also means the loss of a wide spectrum of flora and fauna.

Rash (dermatitis) An inflammation of the upper layers of the skin, causing rash, blisters, scabbing, redness, and swelling. There are many different types of dermatitis, including: acrodermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, diaper rash (diaper dermatitis), exfoliative dermatitis, herpeti-formis dermatitis, irritant dermatitis, occupational dermatitis, perioral dermatitis, photoallergic dermatitis, phototoxic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, and toxi-codendron dermatitis.

Contact Dermatitis (allergic contact dermatitis, contact eczema, irritant contact dermatitis) Contact dermatitis is a reaction that occurs when skin comes in contact with certain substances. There are two mechanisms by which substances can cause skin inflammation: irritation (irritant contact dermatitis) or allergic reaction (allergic contact dermatitis). Common irritants include soap, detergents, acids, alkalis, and organic solvents (as are present in nail polish remover). Contact dermatitis is most often seen around the hands or areas that touched or were exposed to the irritant/allergen. Contact dermatitis of the feet also exists, but it differs in that it is due to the warm, moist conditions in the shoes and socks.

An allergic reaction does not generally occur the first time one is exposed to a particular substance, but it can on subsequent exposures, which can cause dermatitis in 4 to 24 hours.

Treatment includes removal or avoidance of the substance causing the irritation, and cleansing the area with water and mild soap (to avoid infection). A recent recommendation for mild cases is to use a manganese sulfate solution to reduce the itching. Antihis-tamines are generally not very helpful. The most common treatment for severe contact dermatitis is with corticosteroid tablets, ointments, or creams, which diminish the immune attack and the resulting inflammation.

Toxicodendron Dermatitis

When people get urushiol—the oil present in poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac—on their skin, it causes another form of allergic contact dermatitis (see above). This is a T-cell-mediated immune response, also called delayed hypersensitivity, in which the body’s immune system recognizes as foreign and attacks the complex of urushiol derivatives with skin proteins. The irony is that urushiol, in the absence of the immune attack, would be harmless.

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic, itchy inflammation of the upper layers of the skin. often develops in people who have hay fever or asthma or who have family members with these conditions. Most commonly displayed during infanthood, usually disappearing by the age of three or four. Recent medical studies suggest that Staphylococcus aureus (a bacteria) contributes to exacerbation of atopic dermatitis.

Treatment is similar to that of contact dermatitis.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

An inflammation of the upper layers of the skin where scales appear on the scalp, face, and sometimes in other areas. Usually more common in cold weather and often runs in families.

Stasis Dermatitis

A chronic redness, scaling, warmth, and swelling on the lower legs. often results in dark brown skin due to a pooling of blood and fluid under the skin, thus usually displayed by those with varicose veins and edema.

Rate-controlling step (rate-determining step; rate-limiting step) A rate-controlling step in a reaction occurring by a composite mechanism is an elementary reaction, the rate constant for which exerts a dominant effect—stronger than that of any other rate constant— on the overall rate.

Reaumur, Rene-Antoine Ferchault de (1683-1757) French Philosopher, Naturalist Rene Reaumur was born in La Rochelle, France, in 1683. After studying mathematics in Bourges he moved to Paris in 1703 at age 20 and under the eye of a relative. Like most scientists of the time, he made contributions in a number of areas, including meteorology. His work in mathematics allowed him entrance to the Academy of Sciences in 1708. Two years later, he was put in charge of compiling a description of the industrial and natural resources in France, and as a result he developed a broad-based view of the sciences. It also inspired him to invention, which led him into the annals of weather and climate and, ultimately, the invention of a thermometer and temperature scale.

In 1713 Reaumur made spun-glass fibers that were made of the same material as today’s building blocks of Ethernet networking and fiber-optic cable. A few years later, in 1719, after observing wasps building nests, he suggested that paper could be made from wood in response to a critical shortage of papermaking materials (rags) at the time. He also was impressed by the geometrical perfection of the beehive’s hexagonal cells and proposed that they be used as a unit of measurement.

He turned his interests from industrial resources such as steel to temperature, and in 1730 he presented to the Paris Academy his study "A Guide for the Production of Thermometers with Comparable Scales." He wanted to improve the reliability of thermometers based on the work of Guillaume Amontons, though he appears not to be familiar with Fahrenheit’s earlier work.

His thermometer of 1731 used a mixture of alcohol (wine) and water instead of mercury, perhaps creating the first alcohol thermometer, and it was calibrated with a scale he created called the Reaumur scale. This scale had 0° for freezing and 80° for boiling points of water. The scale is no longer used today. However, most of Europe, with the exception of the British Isles and Scandinavia, adopted his thermometer and scale.

Unfortunately, his errors in the way he fixed his points were criticized by many in the scientific community at the time, and even with modifications in the scale, instrument makers favored making mercury-based thermometers. Reaumur’s scale, however, lasted over a century, and in some places well into the late 20th century.

Between 1734 and 1742, Reaumur wrote six volumes of Memoires pour servir a l’histoire des insectes (Memoirs serving as a natural history of insects). Although unfinished, this work was an important contribution to entomology. He also noticed that crayfish have the ability to regenerate lost limbs and demonstrated that corals were animals, not plants. In 1735 he introduced the concept of growing degree-days, later known as Reaumur’s thermal constant of phenology. This idea led to the heat-unit system used today to study plant-temperature relationships.

In 1737 Reaumur became an honorary member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and the following year he became a fellow of the Royal Society.

After studying the chemical composition of Chinese porcelain, in 1740 he formulated his own Reaumur porcelain. In 1750 while investigating the animal world, he designed an egg incubator. Two years later, in 1752, he discovered that digestion is a chemical process by isolating gastric juice and studied its role in food digestion by studying hawks and dogs.

Reaumur died in La Bermondiere on October 18, 1757, and bequeathed to the Academy of Science his cabinet of natural history with his collections of minerals and plants.

Recapitulation The repetition of stages of evolution in the stages of development in the individual organism (ontogeny). The history of the individual development of an organism.