Helix A particular rigid left- or right-handed arrangement of a polymeric chain, characterized by the number of strands, the number (n) of units per turn, and its pitch (p), the distance the helix rises along its axis per full turn. Examples of single-stranded helices are the protein helices: a-helix: n = 3.6, p = 540 picometer; 310-helix: n = 3.0, p = 600 picometer; n-helix: n = 4.4, p = 520 picometer.

Helminth A worm or wormlike organism. Three major helminths exist that affect humans: the nema-todes (roundworm), trematodes (flukes), and cestodes (tapeworms).

Helper T cell A type of T cell needed to turn on antibody production by activating cytotoxic T cells and causing other immune responses in the body. They aid in helping B cells to make antibodies against thymus-dependent antigens. TH1 and TH2 helper T cells secrete materials (interleukins and gamma interferon) that help cell-mediated immune response.

Heme A near-planar coordination complex obtained from iron and the dianionic form of porphyrin. Derivatives are known with substitutes at various positions on the ring named a, b, c, d, etc. Heme b, derived from protoporphyrin ix, is the most frequently occurring heme.

Hemerythrin A dioxygen-carrying protein from marine invertebrates, containing an oxo-bridged dinu-clear iron center.

Hemichordates Consisting of only a few hundred species, the hemichordates include the acorn worms (e.g., Saccoglossus), which burrow in sand and mud, and pterobranchs (e.g., Rhabdopleura), tiny colonial animals. The hemichordates have a tripartite (threefold) division of the body, pharyngeal gill slit, a form of dorsal nerve cord, and a similar structure to a noto-chord. Graptolites, which comprise the class Grap-tolithina, are common fossils in Ordovician and Silurian rocks and are now considered hemichordates.

Hemochromatosis A genetic condition of massive iron overload leading to cirrhosis and/or other tissue damage attributable to iron.

Hemocyanin A dioxygen-carrying protein (from invertebrates, e.g., arthropods and mollusks), containing dinuclear type 3 copper sites. See also nuclearity.

Hemoglobin A dioxygen-carrying heme protein of red blood cells, generally consisting of two alpha and two beta subunits, each containing one molecule of protoporphyrin ix. See also blood.

Hemolymph The body circulatory fluid found in invertebrates, functionally equivalent to the blood and lymph of the vertebrate circulatory system.

Hemophilia An inherited clotting problem that occurs, with few exceptions, in males. It delays coagulation of the blood, making hemorrhage difficult to control. Hemophilia A, called classical or standard hemophilia, is the most common form of the disorder and is due to a deficiency of a factor called factor VIII (FVIII). Hemophilia B, also called Christmas disease, is due to a deficiency of factor IX (FIX). A person with hemophilia does not bleed any faster than a normal person, but the bleeding continues for a much longer time.

Hemorrhoids (piles) Abnormally enlarged or dilated veins around the anal opening.

Hench, Philip Showalter (1896-1965) American Physician Philip Showalter Hench was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on February 28, 1896, to Jacob Bixler Hench and Clara Showalter. After attending local schools he attended Lafayette College, Easton, Pennsylvania, and received a B.A. in 1916. The following year he enlisted in the U.S. Army Medical Corps but was transferred to the reserve corps to finish his medical training. In 1920 he received his doctorate in medicine from the University of Pittsburgh.

He became the head of the Mayo Clinic Department of Rheumatic Disease in 1926, and by 1947 was professor of medicine. During World War II he became a consultant to the army surgeon general. During this period with the Mayo Clinic he isolated several steroids from the adrenal gland cortex and, working with Edward kendall, successfully conducted trials using cortisone on arthritic patients. Hench also treated patients with ACTH, a hormone produced by the pituitary gland that stimulates the adrenal gland. He shared with Edward C. Kendall and Tadeus reichstein the 1950 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for this pioneering work in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with cortisone and ACTH.

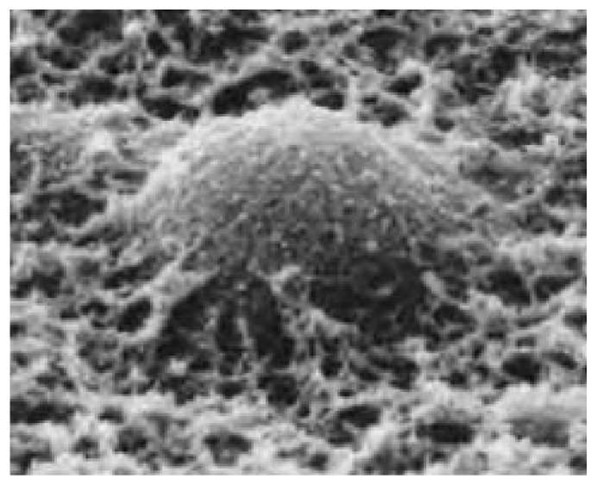

Scanning electron micrograph of a human erythrocyte, or red blood cell, tangled in fibrin. Fibrin is the insoluble form of fibrinogen, a coagulation factor found in solution in blood plasma. Fibrinogen is converted to the insoluble protein fibrin when acted upon by the enzyme thromboplastin. Fibrin forms a fibrous meshwork, the basis of a blood clot, which is the essential mechanism for the arrest of bleeding. Red blood cells contain the pigment hemoglobin, the principal function of which is to transport oxygen around the body. Magnification: x6900 (at 10 x 8 in. size).

He authored many papers in the field of rheumatology, received numerous awards, and belonged to several scientific organizations throughout his life. He died on March 30, 1965, in Ocho Rios, Jamaica.

Hepatic portal vessel A system of veins that delivers blood from glands and organs of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) to the liver. A portal vein enters the liver at the porta hepatis and distributes venules and sinusoids, capillarylike vessels where blood becomes purified, before it goes into the inferior vena cava. The hepatic artery carries oxygen-rich blood to the liver from the heart and mixes with the portal vein in the sinusoids. Thus two filtering systems, the capillaries of the GIT and sinusoids of the liver, perform their tasks on the blood.

Herb Part of a plant that is used for medicinal, food, or aromatic properties.

Herbivore An animal that only eats plants to obtain its necessary nutrients for survival.

Hermaphrodite An individual with both male and female sexual reproductive organs and that functions as both male and female, producing both egg and sperm. The individual can be a simultaneous hermaphrodite, having both types of organs at the same time, or a sequential or successive hermaphrodite that has one type early in life and the other type later. If the female part forms first it is called pro-togynous hermaphroditism; it is called protandrous hermaphroditism if the male forms first.

Some examples of hermaphrodites are most flukes, tapeworms, gastrotriches, earthworms, and even some humans.

In plants, it is when male and female organs occur in the same flower of a single individual.

Hernia A protrusion of a tissue or organ or a part of one through the wall of the abdominal cavity or other area. A hiatal hernia has part of the stomach protruding through the diaphragm and up into the chest and affects about 15 percent of the human population.

Herodotus A Greek who lived ca. 400 b.c.e. and observed fossil seashells in the rocks of mountains. He interpreted these remains as once-living marine organisms and concluded that these areas must have been submerged in the past.

Hess, Walter Rudolf (1881-1973) Swiss Physiologist Walter Rudolf Hess was born in Frauenfeld, in Aargau Canton, Switzerland, on March 17, 1881, to a teacher of physics. He received a doctor of medicine in 1906 from the University of Zurich.

Originally he began his career as an ophthalmologist for six years (1906-12), but dropped his practice and turned to the study of physiology at the University of Bonn. In 1917 he was nominated director of the Physiological Institute at Zurich, with corresponding teaching responsibilities, and later director of the Physiological Institute (1917-51) at the University of Zurich.

He spent most of his life investigating the responses of behavior, respiration, and blood pressure by stimulating the diencephalon of cats using his own techniques. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1949 for his work related to the diencephalon.

Among Hess’s books is The Biology of Mind (1964). He died on August 12, 1973.

Heterochromatin Most cell nuclei contain varying amounts of functional (active) and nonfunctional (inactive) DNA. Functional DNA is called euchromatin, while nonfunctional or inactive is called heterochro-matin. The latter is DNA that is so tightly packaged it cannot transcript. Two forms exist: constitutive hete-rochromatin, where portions of the chromosome are always inactive, and facultative heterochromatin, where portions of the chromosome are active in some cells at one time but are inactive now (such as the Y chromosome and Barr bodies). A gene is closed or inaccessible and not expressed if it is heterochromatin.

Heterochrony An evolutionary change in developmental timing in the relative time or rate of appearance or development of a character. The morphological outcomes of changes in rates and timing of development are paedomorphosis (less growth) or peramorphosis (more growth). Peramorphosis is the extended or exaggerated shape of the adult descendant relative to the adult ancestor; its later ontogenetic stages retain characteristics from earlier stages of an ancestor. Paedomor-phosis is where the adult descendant retains a more juvenile looking shape or looks more like the juvenile form of its adult ancestor; its development goes further than the ancestor and produces exaggerated adult traits. Paedomorphosis can happen as a result of beginning late (postdisplacement), ending early (progensis), or slowing in the growth rate (neoteny). Likewise, per-amorphosis can result from starting early (predisplace-ment), ending late (hypermorphosis), or having a greater growth rate (acceleration).

Heterocyst A large, thick-walled, specialized cell working in anoxic (oxygen absent) conditions that engages in nitrogen fixation from the air on some filamentous cyanobacteria; an autotrophic organism.

Heteroecious A parasite that starts its life cycle on one organism and then affects a second host species to complete the cycle, e.g., peach-potato aphid (Myzus persicae).

Heterogamy Producing gametes of two different types from unlike individuals, e.g., egg and sperm. The tendency for unlike types to mate with unlike types.

Heterolysis (heterolytic cleavage or heterolytic fission)The cleavage of a bond so that both bonding electrons remain with one of the two fragments between which the bond is broken.

Heteromorphic Having different forms at different periods of the life cycle, as in stages of insect metamorphosis and the life cycle of modern plants, where the sporophyte and gametophyte generations have different morphology.

Heteroptera A suborder known as true bugs. They have very distinctive front wings, called hemelytra. The basal half is leathery and the apical half is membranous. They have elongate, piercing-sucking mouthparts. Worldwide in distribution, there are more than 50,000 species. Two families are ectoparasites. The Cimicidae (bed bugs) live on birds and mammals including humans, and the Polyctenidae (bat bugs) live on bats.

Heteroreceptor A receptor regulating the synthesis and/or the release of mediators other than its own ligand. See also autoreceptor.

Heterosexual Having an affection for members of the opposite sex, i.e., male attracted to female.

Heterosis Vigorous, productive hybrids that result from a directed cross between two pure-breeding plant lines.

Heterosporous Producing two types of spores differing in size and sex. Plant sporophytes that produce two kinds of spores that develop into either male or female gametophytes.

Heterotrophic organisms Organisms that are not able to synthesize cell components from carbon dioxide as a sole carbon source. Heterotrophic organisms use preformed oxidizable organic substrates such as glucose as carbon and energy sources, while energy is gained through chemical processes (chemoheterotro-phy) or through light sources (photoheterotrophy).

Heterozygote A diploid organism or cell that has inherited different alleles, at a particular locus, from each parent (i.e., Aa individual); a form of polymorphism.

Heterozygote advantage (overdominance) The evolutionary mechanism that ensures that eukaryotic het-erozygote individuals (Aa) leave more offspring than homozygote (AA or aa) individuals, thereby preserving genetic variation; condition in which heterozygotes have higher fitness than homozygotes.

Heterozygous Two different alleles of a particular gene present within the same cell; a diploid individual having different alleles of one or more genes producing gametes of different genotypes.

Heymans, Corneille Jean-Francois (1892-1968) Belgian Physiologist Corneille Jean-Frangois Heymans was born in Ghent, Belgium, on March 28, 1892, to J. F. Heymans, a former professor of pharmacology and rector of the University of Ghent, and who founded the J. F. Heymans Institute of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at the same university.

Corneille received his secondary education at the St. Lievens College (Ghent), St. Jozefs College (Turn-hout), and St. Barbara College (Ghent). He pursued his medical education at the University of Ghent and received a doctor’s degree in 1920. After graduation he worked at various colleges until 1922, when he became lecturer in pharmacodynamics at the University of Ghent. In 1930 he succeeded his father as professor of pharmacology and was appointed head of the department of pharmacology, pharmacodynamics, and toxicology; at the same time he became director of the J. F. Heymans Institute, retiring in 1963.

His research was directed toward the physiology and pharmacology of respiration, blood circulation, metabolism, and pharmacological problems. He discovered chemoreceptors in the cardio-aortic and carotid sinus areas, and made contributions to knowledge of arterial blood pressure and hypertension. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 1938 for his work on the regulatory effect of the cardio-aortic and the carotid sinus areas in the regulation of respiration.

Hibernation A physiological state of dormancy, a sleeplike condition, that lowers body temperature,slows the heart and breathing, and reduces the need for food for extended periods of time, usually during periods of cold. Examples of hibernators are bears, bats, snakes, frogs, squirrels, turtles, and some birds.

Hill, Archibald Vivian (1886-1977) British Physiologist Archibald Vivian Hill was born in Bristol on September 26, 1886. After an early education at Blun-dell’s School, Tiverton, he entered Trinity College, Cambridge, with scholarships. He studied mathematics but was urged to go into physiology by one of his teachers, Walter Morley Fletcher.

In 1909 he began study on the nature of muscular contraction and the dependence of heat production on the length of muscle fiber. From 1911 to 1914, until the start of World War I, he continued his work on the physiology of muscular contraction at Cambridge as well as other studies on nerve impulse, hemoglobin, and calorimetry.

In 1926 he was appointed the Royal Society’s Foulerton research professor and was in charge of the biophysics laboratory at University College until 1952.

His work on muscle function, especially the observation and measurement of thermal changes associated with muscle function, was later extended to similar studies on the mechanism of the passage of nerve impulses. He coined the term oxygen debt to describe the process of recovery after exercise.

He discovered and measured heat production associated with nerve impulses and analyzed physical and chemical changes associated with nerve excitation, among other studies. In 1922 he won the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine (with Otto meyerhof) for work on chemical and mechanical events in muscle contraction such as the production of heat in muscles. This research helped establish the origin of muscular force in the breakdown of carbohydrates while forming lactic acid in the muscle.

His important works include Muscular Activity (1926), Muscular Movement in Man (1927), Living Machinery (1927), The Ethical Dilemma of Science and Other Writings (1960), and Traits and Trials in Physiology (1965).

He was a member of several scientific societies and was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1918, serving as secretary for the period 1935-45, and foreign secretary in 1946. Hill died on June 3, 1977.

Hill topping A behavior exhibited by butterflies where males and females congregate at a high point in the landscape, increasing each individual butterfly’s chance of finding a mate.

Hilum The area where blood vessels, nerves, and ducts enter an organ.

HIPIP Formerly used abbreviation for high-potential iron-sulfur protein, now classed as a ferredoxin. An electron transfer protein from photosynthetic and other bacteria, containing a [4fe-4s] cluster that undergoes oxidation-reduction between the [4Fe-4S]2+ and [4Fe-4S]3+ states.

Hirudin A nonenzymatic chemical secreted from the leech that prevents blood clotting. Today, the genetically engineered lepirudin and desirudin and the synthetic bivalirudin are used as anticoagulants.

Histamine A hormone and chemical transmitter found in plant and animal tissues. In humans it is involved in local immune response that will cause blood vessels to dilate during an inflammatory response; also regulates stomach acid production, dilates capillaries, and decreases blood pressure. It increases permeability of the walls of blood vessels by vasodilation when released from mast cells and causes the common symptoms of allergies such as running nose and watering eyes. It will also shut the airways in order to prevent allergens from entering, making it difficult to breath. Antihistamines are used to counteract this reaction.

Histology The study of the microscopic structure of plant and animal tissue.

Histone A basic unit of chromatin structure; several types of protein characteristically associated with the DNA in chromosomes in the cell nucleus of eukaryotes. They function to coil DNA into nucleosomes, which are a combination of eight histones (a pair each of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) wrapped by two turns of a DNA molecule. A high number of positively charged amino acids bind to the negatively charged DNA.

Holoblastic cleavage A complete and equal division of the egg in an early embryo that has little yolk. Characteristic of amphibians, mammals, nonvertebrate chordates, echinoderms, most mollusks, annelids, flat-worms, and nematodes.

Holocene The present epoch of geological time starting approximately 10,000 years ago to the present. See also geological time.

Holoenzyme An enzyme containing its characteristic prosthetic group(s) and/or metal(s).

Holotype The exact specimen of a new animal or plant representing what is meant by the new name and designated so by publication. The holotype specimen does not have to be the first ever collected, but it is the official one with which all others are compared.

Homeobox (HOX genes) A short stretch of similar or identical 180-base-pair (nucleotide) sequences of DNA within a homeotic gene in most eukaryotic organisms that plays a major role in controlling body development by regulating patterns of differentiation. Homeot-ic genes create segments in an embryo that become specific organs or tissues. Homeoboxes determine positional cell differentiation and development. Mutations in these genes will cause one body part to convert into a totally different one.

Homeosis The replacement of one body part by another caused by mutations or environmental factors initiating developmental anomalies.

Homeostasis The ability of an organism to automatically maintain a constant internal condition regardless of the external environment.