Chemoautotroph (chemolithotroph) An organism that uses carbon dioxide as its carbon source and obtains energy by oxidizing inorganic substances.

Chemoheterotroph Any organism that derives its energy by oxidizing organic substances for both a carbon source and energy.

Chemoreceptor A sense organ, cell, or structure that detects and responds to chemicals in the air or in solution.

Chemotherapy The treatment of killing cancer cells by using chemicals. See also cancer.

Chiasma The x-shaped point or region where homologous chromatids have exchanged genetic material through crossing over during meiosis. The term is also applied to the site where some optic nerves from each eye cross over to the opposite side of the brain, forming the optic tract.

Chigger Red, hairy, very small mites (arachnids) of the family Trombiculidae, such as Trombicula alfreddugesi and T. splendens Ewing. Also called jiggers and redbugs. Chiggers cause skin irritation in humans and dermatitis in animals.

Chigoe flea A flea (Tunga penetrans) that attacks bare feet and causes nodular swellings and ulcers around toenails, as well as between the toes and the sole.

Chirality A term describing the geometric property of a rigid object (or spatial arrangement of points or atoms) that is nonsuperimposable on its mirror image; such an object has no symmetry elements of the second kind (a mirror plane, a center of inversion, a rotation reflection axis). If the object is superimposable on its mirror image, the object is described as being achiral.

Chi-square test A statistical exercise that compares the frequencies of various kinds or categories of items in a random sample with the frequencies that are expected if the population frequencies are as hypothesized by the researcher.

Chitin The long-chained structural polysaccharide found in the exoskeleton of invertebrates such as crustaceans, insects, and spiders and in some cell walls of fungi. A beta-1,4-linked homopolymer of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine.

Chlamydospore A thick-walled asexual resting spore of certain fungi assuming a role for survival in soil or in decaying crop debris from year to year.

Chlorin In organic chemistry, it is an unsubstituted, reduced porphyrin with two nonfused saturated carbon atoms (C-2, C-3) in one of the pyrrole rings.

Chlorophyll Part of the photosynthetic systems in green plants. Generally speaking, it can be considered as a magnesium complex of a porphyrin in which a double bond in one of the pyrrole rings (17-18) has been reduced. A fused cyclopentanone ring is also present (positions 13-14-15). In the case of chlorophyll a, the substituted porphyrin ligand further contains four methyl groups in positions 2, 7, 12, and 18, a vinyl group in position 3, an ethyl group in position 8, and a -(CH2)2CO2R group (R=phytyl, (2E)-(7R, 11R)-3,7, 11,15-tetramethylhexadec-2-en-1-yl) in position 17. In chlorophyll b, the group in position 7 is a -CHO group. In bacteriochlorophyll a, the porphyrin ring is further reduced (7-8), and the group in position 3 is now a -COCH3 group. In addition, in bacteriochlorophyll b, the group in position 8 is a =CHCH3 group.

Chloroplast The double membrane organelle of eukaryotic photosynthesis; contains enzymes and pigments that perform photosynthesis.

Cholera An acute infection of the small intestines by Vibrio cholerae that is transmitted by ingesting fecal-contaminated water or food, or raw or undercooked seafood. Symptoms include diarrhea, abdominal cramps, nausea, vomiting, and severe dehydration. Endemic to India, Africa, the Mediterranean, South and Central America, Mexico, and the United States. Highly infectious disease that can be fatal, but there is a vaccine against it.

Cholesterol A soft, waxy, fat-soluble steroid formed by the liver and a natural component of fats in the bloodstream (as lipoproteins); most common steroid in the human body and used by all cells in permeability of their membranes. It is used in the formation of many products such as bile acids, vitamin D, progesterone, estrogens, and androgens. In relation to human health, there is the high-density "good" cholesterol (HDL), which protects the heart, and the low-density "bad" cholesterol (LDL), which causes heart disease and other problems.

chondrichthyes Cartilaginous fishes; internal skeletons are made of cartilage and reinforced by small bony plates, while the external body is covered with hooklike scales. There are over 900 species in two sub classes, Elasmobranchii (sharks, skates, and rays) and Holocephali (chimaeras).

Chondrin A substance that forms the matrix of cartilage, along with collagen; formed by chondrocytes.

Chordate one of the most diverse and successful animal groups. The phylum Chordata includes fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals, and two invertebrates (tunicates and lancelets). Characterized by having at various times of their life a notochord (primitive spine, skeletal rod), pharyngeal slits, and hollow nerve cord ending in the brain area; usually have a head, a tail, and a digestive system, with an opening at both ends of the body. Their bodies are elongate and bilaterally symmetrical. Includes the hemichordates (vertebrates), cephalochordates (e.g., amphioxus), and urochordates (e.g., sea squirts).

Chorion one of the four extraembryonic membranes, along with amnion, yolk sac, and allantois. It contributes to the formation of the placenta in mammals; outermost membrane.

Chorionic villus sampling A prenatal diagnosis technique that takes a small sample of tissue from the placenta and tests for certain birth defects. This is an early detection test, as it can be performed 10 to 12 weeks after a woman’s last menstrual cycle.

Chromatin The combination of DNA and proteins that make up the chromosomes of eukaryotes. Exists as long, thin fibers when cells are not dividing; not visible until cell division takes place.

Chromatography A method of chemical analysis where a compound is separated by allowing it to migrate over an absorbent material, revealing each of the constituent chemicals as separate layers.

Chromista Brown algae, diatoms, and golden algae, placed together under a new proposed kingdom name.

Chromophore That part of a molecular entity consisting of an atom or group of atoms in which the electronic transition responsible for a given spectral band is approximately localized.

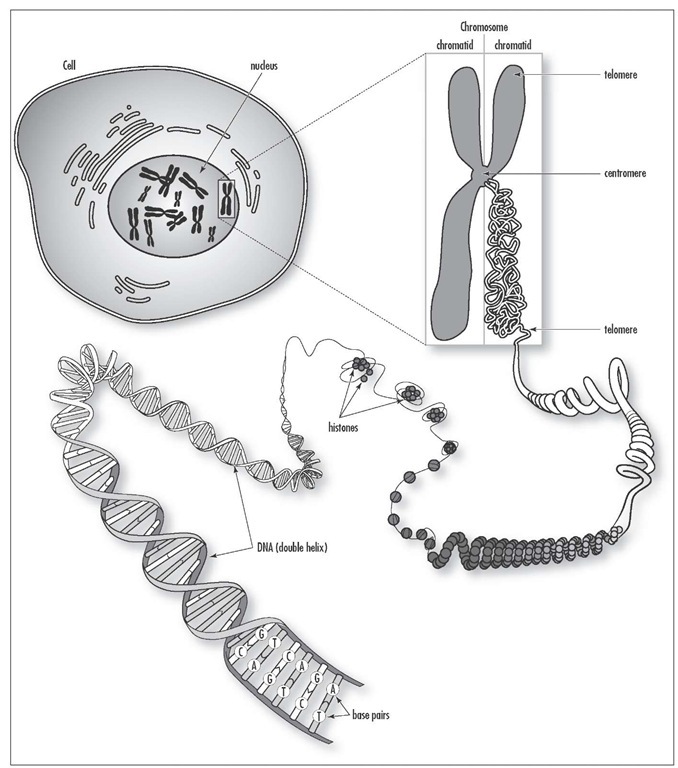

Chromosome The self-replicating gene-carrying member found in the cell nucleus and composed of a DNA molecule and proteins (chromatin). Prokaryote organisms contain only one chromosome (circular DNA), while eukaryotes contain numerous chromosomes that comprise a genome. Chromosomes are divided into functional units called genes, each of which contains the genetic code (instructions) for making a specific protein. See also gene.

Chronic Long lasting and severe; the opposite of acute. Examples of chronic diseases include: chronic atopic dermatitis; chronic bronchitis; chronic cough; chronic rhinitis; chronic ulcerative colitis.

Chytrid A group of fungi not completely understood by science. Not visible to the eye, they are small, with a mycelium and central sporophore, looking like a miniature octopus. They reproduce by means of self-propelling spores.

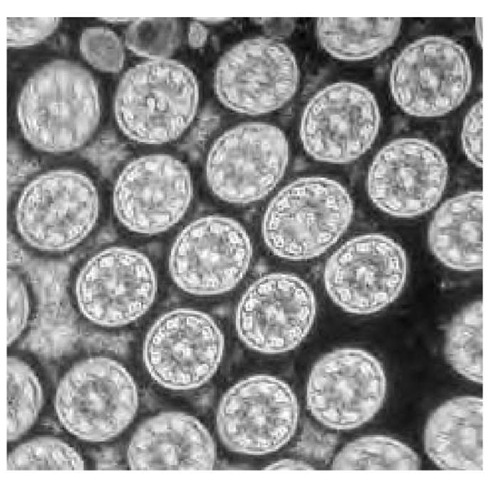

Cilium (plural, cilia) A hair-like oscillating structure that is used for locomotion or for moving particles. It projects from a cell surface and is composed of nine outer double microtubules with two inner single microtubules, and it is anchored by a basal body. Single-cell organisms, such as protozoa, use them for locomotion. The human female fallopian tubes use cilia to transport the egg from the ovary to the uterus.

Human Cytogenetics: Historical Overview and Latest Developments

by Betty Harrison

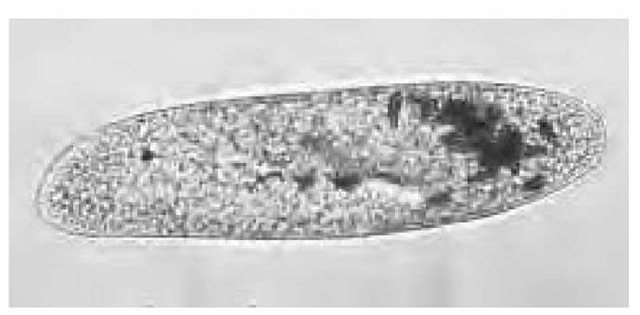

A single-celled organism, Paramecium caudatum, that uses cilia for locomotion.

A chromosome is one of the threadlike "packages" of genes and other DNA in the nucleus of a cell. Different kinds of organisms have different numbers of chromosomes. Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes, 46 in all: 44 autosomes and two sex chromosomes. Each parent contributes one chromosome to each pair, so children get half of their chromosomes from their mothers and half from their fathers.

Cytogenetics, the study of chromosomes, was revolutionized by the discovery that quinicrine staining under ultraviolet light produces a unique banding pattern. In 1970, Dr. Torbjorn O. Caspersson and his group discovered that human chromosomes fluoresce when stained with quini-crine mustard, giving a distinct banding pattern to each chromosome pair. It was later found that chromosomes show a similar banding pattern with the use of stain. Giemsa/Trypsin or Wright’s/Trypsin stain is now preferable to quinicrine, as they allow the use of the light microscope and also provide stable preparations.

Banding of chromosomes allows pairing of, rather than grouping of, homologous chromosomes of similar size. The number of bands identified is routinely between 450 and 550, and high resolution is 550 and higher bands in a haploid set. A band is a region that is distinguishable from a neighboring region by the difference in its staining intensity. Banding permits a more detailed analysis of chromosome rearrangements such as translocations, deletions, duplications, insertions, and inversions.

Several types of banding procedures have been developed since the early 1970s in addition to Giemsa banding. R-banding or reverse banding is the opposite of Giemsa (Wright’s) banding pattern. There are staining techniques for specific regions of the chromosomes: silver staining, which stains the nucleolus-organizing regions (NORs), and C-banding (constitutive heterochromatin), which stains the centromere of all chromosomes and the distal portion of the Y chromosome. The size of the C-band on a given chromosome is usually constant in all cells of an individual but is highly variable from person to person.

The development of banding techniques in the early 1970s was followed by the development of "high resolution banding" in the late 1970s. This technique divides the landmark bands into sub-bands of contrasting shades of light and dark regions. High-resolution or extended banding is produced by a combination of the induction of cell synchronization followed by the precise timing of harvesting. The cells are then examined in prophase, prometaphase, and early metaphase. At these stages of cell division, very small chromosome changes can be detected. This is useful clinically to find previously undetected chromosome aberrations not found at lower banding levels, to localize breakpoints in rearranged chromosomes, and to help establish phenotype-genotype relationships at a more precise level.

The normal chromosome complement of 46 is called diploid. If there are 46 chromosomes with structural abnormalities, it is referred to as pseudodiploid. Numerical abnormalities are called aneuploidy. When there are more than 46, it is called hyperdiploid, and when fewer, it is called hypodiploid. Chromosome loss in whole or part is a mono-somy, while the gain of a single chromosome when they are paired is a trisomy. The presence of two or more cell lines in an individual is known as mosaicism. When, for example, the abnormal line is a trisomy with a normal line, the overall phenotypic effect of the extra chromosome is generally decreased.

The types of cells examined are usually from peripheral blood, bone marrow, amniotic fluid, chorionic villi, and solid-tissue biopsies. These tissues are analyzed in diagnostic procedures in prenatal diagnosis, multiple miscarriages, newborns and children with abnormal phenotypes and abnormal sexual development, hematological disorders, and solid tumors. Autosomal chromosome abnormalities generally have more serious consequences than sex chromosome abnormalities. Chromosome abnormalities are a major cause of fetal loss. These numbers decrease by birth, and since some trisomies result in early death, their frequency is lower in children and even lower in adults.

Numerical changes a re the most common chromosome abnormalities. Most numerical changes are the result of nondisjunction in the first meiotic division. Mitotic nondisjunction typically results in mosaicism. Chromosome structural changes can be balanced or unbalanced. Structural abnormalities may be losses, rearrangements, or gains, while numerical abnormalities are losses or gains. Both numerical and structural changes may result in pheno-typic abnormalities.

Chromosome abnormalities may be constitutional or acquired. Constitutional abnormalities may be associated with phenotypic anomalies (i.e., Down’s syndrome, Turner syndrome) or result in a normal phenotype (i.e., balanced familial translocation). Acquired abnormalities are usually those associated with malignant transformation, such as cancers.

A significant advance in the past decade has been the addition of fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) or molecular cytogenetics. FISH has become both a diagnostic and a research tool in cytogenetic laboratories. These procedures involve the denaturation of DNA followed by hybridization with a specific probe that has been tagged with a fluo-rochrome and stained with a counterstain. These preparations are viewed through a fluorescent microscope with a 100-W mercury lamp and appropriate filter sets.

FISH, for example, provides rapid results in prenatal diagnosis. Chromosome analysis using classical chromosome analysis on cultured cells from amniotic fluid takes 1-2 weeks to complete. FISH is performed on the uncultured amniocytes and is complete in 24-48 hours. FISH screens for only numerical abnormalities in chromosomes 13, 18, 21, X, and Y. However, these chromosomes make up approximately 90 percent of the total chromosome abnormalities that result in birth defects.

FISH can be used for identification of marker chromosomes, microdeletion syndromes, rearrangements and deletions, detection of abnormalities in leukemia, myelopro-liferative disorders, and solid tumors. For example, a chromosome deletion not clearly visible with standard chromosome analysis may be detected with a specific probe for the region (i.e., Di George syndrome).

Cytogenetic analysis of malignant cells proved valuable in the diagnosis and in some cases prognosis of hematological malignancies. FISH has increased the importance of chromosome analysis in the diagnosis of these patients. Many nonrandom cytogenetic abnormalities associated with a specific hematological malignancy have been found. These findings have contributed to the understanding and in some cases treatment of these malignancies. The use of

FISH techniques has greatly improved the diagnostic accuracy because, in addition to specific translocation probes, FISH can detect abnormalities in both interphase and metaphase cells.

A current FISH test that may be used for the identification of subtle rearrangements or to characterize complex translocations involving more than two chromosomes is spectral karyotyping (M-FISH, or multiplex in-situ hybridization). This test simultaneously identifies entire chromosomes using 24 different colors.

Recent research using telomere probes in cases of unexplained mental retardation has revealed that approximately 6 percent may be due to subtelomere rearrangements.

An additional research tool, especially in cancer cyto-genetics, is comparative genomic hybridization (CGH). This technique reveals whole chromosome gains and losses as well as deletions and amplifications of very small chromosome segments. Cytogenetic analysis has been an extremely valuable tool for screening and for diagnosing genetic disorders, and it will continue to play a vital role in medical service and research.

Colored transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of a cross section through cilia (circles), from the lining (epithelium) of the human trachea, or windpipe. Cilia in the trachea are hairlike projections that beat rhythmically to move mucus away from the gas-exchanging parts of the lungs, up toward the throat where it can be swallowed or coughed up. They project in parallel rows, with 300 on each cell, measuring up to 10 pm in length. Each cillium contains a central core (axoneme), which consists of 20 microtubules arranged as a central pair, surrounded by nine peripheral doubtlets (as seen). Magnification: x40,000 at 6 x 7 cm size.

Circadian rhythm A biological process that oscillates with an approximate 24-hour periodicity, even if there are no external timing cues; an internal daily biological clock present in all eukaryotes.