Celsius, Anders (1701-1744) Swedish Astronomer, Physicist Anders Celsius was a Swedish astronomer, physicist, and mathematician who introduced the Celsius temperature scale that is used today by scientists in most countries. He was born in Uppsala, Sweden, a city that has produced six Nobel Prize winners. Celsius was born into a family of scientists, all originating from the province of Halsingland. His father Nils Celsius was a professor of astronomy, as was his grandfather Anders Spole. His other grandfather, Magnus Celsius, was a professor of mathematics. Both grandfathers were at the university in Uppsala. Several of his uncles were also scientists.

Celsius’s important contributions include determining the shape and size of the Earth; gauging the magnitude of the stars in the constellation Aries; publication of a catalog of 300 stars and their magnitudes; observations on eclipses and other astronomical events; and a study revealing that the Nordic countries were slowly rising above the sea level of the Baltic. His most famous contribution falls in the area of temperature, and the one he is remembered most for is the creation of the Celsius temperature scale.

In 1742 he presented to the Swedish Academy of Sciences his paper, "Observations on Two Persistent Degrees on a Thermometer," in which he presented his observations that all thermometers should be made on a fixed scale of 100 divisions (centigrade) based on two points: 0° for boiling water, and 100° for freezing water. He presented his argument on the inaccuracies of existing scales and calibration methods and correctly presented the influence of air pressure on the boiling point of water.

After his death, the scale that he designed was reversed, giving rise to the existing 0° for freezing and 100° for boiling water, instead of the reverse. It is not known if this reversal was done by his student Martin Stromer; or by botanist Carolus Linnaeus, who in 1745 reportedly showed the senate at Uppsala University a thermometer so calibrated; or if it was done by Daniel Ekstrom, who manufactured most of the thermometers used by both Celsius and Linneaus. However, Jean Christin from France made a centigrade thermometer with the current calibrations (0° freezing, 100° boiling) a year after Celsius and independent of him, and so he may therefore equally claim credit for the existing "Celsius" thermometers.

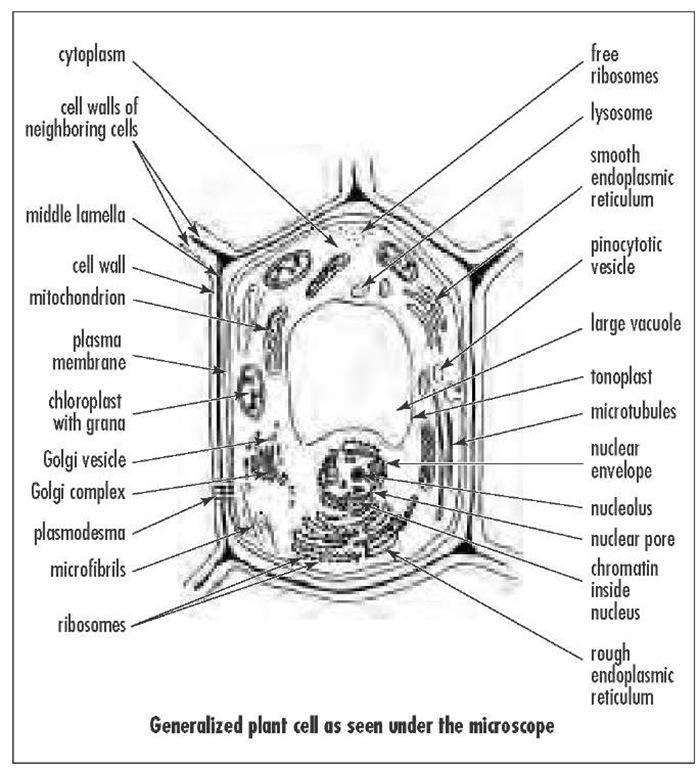

All cells have cell walls that provide a tough surrounding layer for a cell.

For years Celsius thermometers were referred to as "centigrade" thermometers. However, in 1948, the Ninth General Conference of Weights and Measures ruled that "degrees centigrade" would be referred to as "degrees Celsius" in his honor. The Celsius scale is still used today by most scientists.

Anders Celsius was secretary of the oldest Swedish scientific society, the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala, between 1725-44 and published much of his work through that organization, including a math book for youth in 1741. He died of tuberculosis on April 25, 1744, in Uppsala.

Celsius scale (centigrade scale) A temperature scale with the range denoted by °C. The normal freezing point of water is 0°C, and the normal boiling point of water is 100°C. The scale was named after Anders Celsius, who proposed it in 1742 but designated the freezing point to be 100 and the boiling point to be 0 (reversed after his death). See also celsius, anders.

Cenozoic era Age of the mammals. The present geological era, beginning directly after the end of the Mesozoic era, 65 million years ago, and divided into the Quaternary and Tertiary periods. See also geologic time.

Central atom The atom in a coordination entity that binds other atoms or group of atoms (ligands) to itself, thereby occupying a central position in the coordination entity.

Central nervous system That part of the nervous system that includes the brain and spinal cord. The brain receives and processes signals delivered through the spinal cord, where all signals are sent and received from all parts of the body, and in turn the brain then sends directions (signals) to the body.

Centriole A pair of short, cylindrical structures composed of nine triplet microtubules in a ring; found at the center of a centrosome; divides and organizes spindle fibers during mitosis and meiosis. See also centrosome.

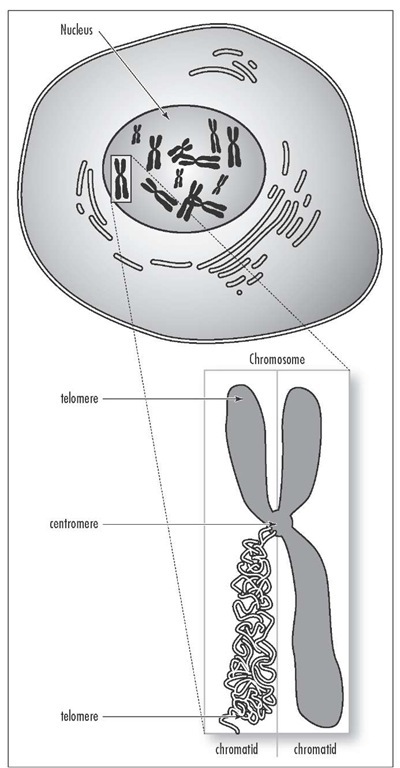

Centromere A specialized area, the constricted region, near the center of a chromosome to which spindle fibers attach during cell division; the location where the two sister chromatids are joined to one another.

Centrosome (microtubule organizing center) The structural organizing center in cell cytoplasm, near the nucleus, where all microtubules originate; if folded it can become a centriole or a basal body for cilia and flagella.

Cephalic Pertains to the head.

Cephalochordate A chordate with no backbone (subphylum Cephalochordata), eg., lancelets.

The centromere is the constricted region near the center of a human chromosome. This is the region of the chromosome where the two sister chromatids are joined to one another.

Cerebellum A part of the vertebrate hindbrain; controls muscular coordination in both locomotion and balance.

Cerebral cortex The outer surface (3-5 mm) of the cerebrum and the sensory and motor nerves. It controls most of the functions that are controlled by the cerebrum (consciousness, the senses, the body’s motor skills, reasoning, and language) and is the largest and most complex part of the mammalian brain. The cortex is broken up into five lobes, each separated by an indentation called a fissure: the frontal lobe, the parietal lobe, the temporal lobe, the occipital lobe, and the insula. It is composed of six layers that have different densities and neuron types from the outermost to innermost: molecular layer, external granular layer, external pyramidal layer, internal granular layer, internal pyramidal layer, and the multiform layer. Vertical columns of neurons run through the layers.

Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of neurons (nerve cells) from the human cerebral cortex (the outer, heavily folded, grey matter of the brain). Neurons exist in varying sizes and shapes throughout the nervous system, but all have a similar basic structure: a large central cell body (large, light-gray bodies) containing a nucleus and two types of processes. These are a single axon (a nerve fiber), which is the effector part of the cell that terminates on other neurons (or organs), and one or more dendrites, smaller processes that act as sensory receptors. Similar types of neurons are arranged in layers within the cerebral cortex. Magnification: x3,000 at 8 x 8 in. x890 at 6 x 6 cm size.

Cerebrum The largest part of the brain; divided into two hemispheres (right and left) that are connected by nerve cells called the corpus callosum. It is the most recognized part of the brain and comprises 85 percent of its total weight. The cerebrum is where consciousness, the senses, the body’s motor skills, reasoning, and language take place.

Ceruloplasmin A copper protein present in blood plasma, containing type 1, type 2, and type 3 copper centers, where the type 2 and type 3 are close together, forming a trinuclear copper cluster.

Chain, Ernst Boris (1906-1979) German Biochemist Ernst Boris Chain was born on June 19, 1906, in Berlin, to Dr. Michael Chain, a chemist and industrialist. He was educated at the Luisen gymnasium, Berlin, with an interest in chemistry. He attended the Friedrich-Wilhelm University, Berlin, and graduated in chemistry in 1930. After graduation he worked for three years at the Charite Hospital, Berlin, on enzyme research. In 1933, after the rise of the Nazi regime in Germany, he left for England.

In 1935 he was invited to Oxford University, and in 1936 he became a demonstrator and lecturer in chemical pathology. In 1948 he was appointed scientific director of the International Research Centre for Chemical Microbiology at the Istituto Superiore di San-ita, Rome. He became professor of biochemistry at Imperial College, University of London, in 1961, serving in that position until 1973. Later, he became a professor emeritus and a senior research fellow (1973-76) and a fellow (1978-79).

From 1935 to 1939 he worked on snake venoms, tumor metabolism, the mechanism of lysozyme action, and the invention and development of methods for biochemical microanalysis. In 1939 he began a systematic study of antibacterial substances produced by microorganisms and the reinvestigation of penicillin. Later he worked on the isolation and elucidation of the chemical structure of penicillin and other natural antibiotics.

With pathologist Howard Walter florey (later Baron Florey), he isolated and purified penicillin and performed the first clinical trials of the antibiotic. For their pioneering work on penicillin Chain, Florey, and Fleming shared the 1945 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine.

Later his research topics included the carbohydrate-amino acid relationship in nervous tissue, a study of the mode of action of insulin, fermentation technology, 6-aminopenicillanic acid and penicillinase-stable penicillins, lysergic acid production in submerged culture, and the isolation of new fungal metabolites.

Chain was the author of many scientific papers and a contributor to important monographs on penicillin and antibiotics, and was the recipient of many awards including being knighted in 1969. He died on August 12, 1979.

Channels Transport proteins that act as gates to control the movement of sodium and potassium ions across the plasma membrane of a nerve cell.

Chaparral Dense vegetation of fire-adapted thick shrubs and low trees living in areas of little water and extreme summer heat in the coastal and mountainous regions of California. Similar community types exist in the coastal and mountainous regions of South Africa (fynbos), Chile (matorral), Spain (maquis), Italy (mac-chia), and Western Australia (kwongan). Also referred to as coastal sagebrush.

Chaperonin A member of the set of molecular chap-erones, located in different organelles of the cell and involved either in transport of proteins through blomembranes (by unfolding and refolding the proteins) or in assembling newly formed polypeptides.

Character A synonym for a trait in taxonomy.

Character displacement The process whereby two closely related species interact in such a way, such as intense competition between species, as to cause one or both to diverge still further. This is most often apparent when the two species are found together in the same environment, e.g., large and small mouth bass.

Charge-transfer complex An aggregate of two or more molecules in which charge is transferred from a donor to an acceptor.

Charge-transfer transition An electronic transition in which a large fraction of an electronic charge is transferred from one region of a molecular entity, called the electron donor, to another, called the electron acceptor (intramolecular charge transfer), or from one molecular entity to another (intermolecular charge transfer).

Chelation Chelation involves coordination of more than one sigma-electron pair donor group from the same ligand to the same central atom. The number of coordinating groups in a single chelating lig-and is indicated by the adjectives didentate, tridentate, tetradentate, etc.

Chelation therapy The judicious use of chelating (metal binding) agents for the removal of toxic amounts of metal ions from living organisms. The metal ions are sequestered by the chelating agents and are rendered harmless or excreted. Chelating agents such as 2,3-dimercaptopropan-1-ol, ethylenediaminete-traacetic acid, desferrioxamine, and D-penicillamine have been used effectively in chelation therapy for arsenic, lead, iron, and copper, respectively. See also chelation.

Chemical equilibrium The condition when the forward and reverse reaction rates are equal and the concentrations of the products remain constant. Called the law of chemical equilibrium.

Chemiosmosis A method of making atp that uses the electron transport chain and a proton pump to transfer hydrogen protons across certain membranes and then utilize the energy created to add a phosphate group (phosphorylate) to ADP, creating ATP as the end product.