Public arenas

In the example of Jura households,it might be argued that the patterns of bone deposition were simply the result of repeated routines. In that case, one could suggest either that people were barely conscious of the symbolisms involved, or, as I prefer, that these were deeply embedded in daily life. In the case of longhouses in the Aisne valley and elsewhere, the same possibilities may apply. There is also the question of timescale. It is not certain over what period of time such bone deposits formed in the relatively shallow flanking ditches in question. One suggestion is that flanking ditches, at least on loess soils, would have filled in very quickly by natural erosional processes (Stauble 1990; Uerpmann and Uerpmann 1997, 574). In this case, the use of animals as symbols would have been a feature especially of the foundation of a household, and this may have become embedded as memory in the routine use of the physical structure.

Neither kind of reservation seems to apply to the deposits made in the ditches of enclosures. Much of the best evidence comes from the fourth millennium BC, when such arenas were widely distributed through many parts of western Europe, from central-western France to southern Scandinavia, with important examples also in the Rhineland, as well as in southern Britain.Like so much else, these are very diverse, but there is a persistent, recurrent and widespread tradition of deliberate deposition in ditches as well as in associated pits. Unless one were to go back to the very first interpretations of enclosure ditches as occupation areas, this practice must indicate deliberate and conscious deposition in arenas that by many other criteria (Bradley 1998a) can be marked out as special. Few examples show a single foundation deposit only, and repeated (though of course varied) depositions are much more common. The character of individual deposits, however, is often small-scale and intimate. The first interpreters such as Curwen in southern Britain (see Oswald et al. 2001) were right to the extent that these are transformations of material important in the domestic sphere, and re-presented in the more public space of arenas at a scale recalling that of the former.

Though in total the numbers of animal bones at many of these enclosures can be impressive, representing potentially hundreds if not thousands of animals even at individual sites, the individual act of deposition often involved a far smaller set of symbols. Three recently published sites from southern Britain can serve as good examples. At Windmill Hill, it seems clear that deposition varied within and between the three ditch circuits and it is dangerous to over-generalise, but there were recurrent finds in all three circuits, not only of linear spreads of material but also of concentrated deposits, set in ditch terminals and at intervals within the individual ditch segments. These proved to be very varied in terms of composition and history as measured by the degree of fragmentation (Grigson 1999), but the selection of the partial remains of a number of animals for inclusion in individual deposits was recurrent. The placed deposit 630, from above the primary fill of the inner ditch,shows various fragmented cattle bones and skull fragments, the latter probably from the same animal. There was also a sheep/goat tibia, and part of the femur of a young human was found inserted in the shaft of an ox humerus. Other placed deposits have the partial remains of cow, sheep/goat, pig and sometimes dog. More complete remains, possible examples of ‘conspicuous non-consumption’ (Grigson 1999, 229), are much less common. Sherds of weathered pottery also add to the impression of selection and transformation; many of these deposits may not have gone straight into the ground following the acts of slaughter, butchery and eating which the bones partially represent. It may be that the selections made acted metonymically, so that the token amount deposited could have stood for a much larger whole, basically beyond meaningful quantification, but the recurrent individuality of the placed deposits is striking and surely significant in its own right.

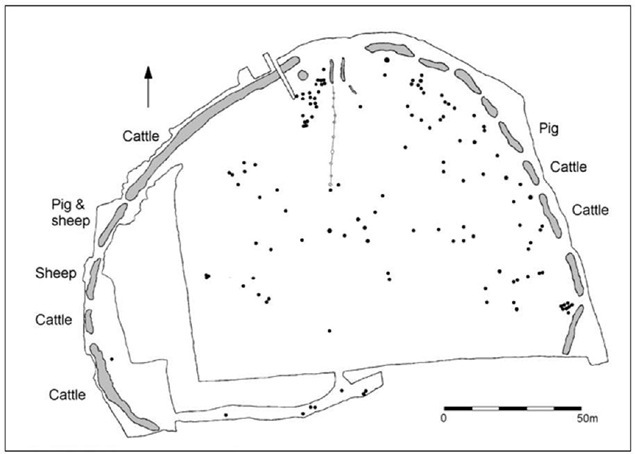

At Etton, the scale of excavation allowed an even more extensive view of patterns of deposition around the enclosure (Pryor 1998). From the low-lying situation and the evidence for flooding, it is extremely unlikely that people were permanently at the site. There is evidence, however, from ditch segment 1 in the south-west part of the enclosure for the keeping of livestock, in the form of enhanced phosphate levels and remains of dung-feeding insects (Pryor 1998, 355). As at Windmill Hill and other sites of this kind, animal bone constituted a regular presence in the ditch segments of the enclosure, more or less right around the enclosure, and in the phases of successive recutting and filling of the ditch segments. The densities were not even. Animal bone and other material was used to enhance the significance of ditch terminals, and presumably thereby that of entrances. The quantities of bone otherwise vary from segment to segment without any obvious correlation with the length of each segment. What does seem striking is the tendency for different species to dominate segment by segment (recalling, in a general way, practices seen beside Aisne longhouses), in phase 1A in the western arc for example (Pryor 1998, fig. 107; Armour-Chelu 1998) cattle in segments 1, 2 and 5, sheep in segment 3, and pigs and sheep in segment 4, and in the eastern arc pig in segment 10 but cattle in segments 11 and 12 (Figure 4.4). In the eastern arc in phase 1A, in segments 6 and 7, there were deposits placed at intervals along the base of the ditches of a kind not found elsewhere, including complete pots, human and animal skulls, animal bones and antler; other segments in this eastern arc in this phase had been backfilled with gravel and topsoil dug from them. In this phase and in 1B, perhaps in contrast to the more continuous deposits of phase 1C, it is recognised as possible that these were individual events separated in time (Pryor 1998, 358).

Figure 4.4 Outline trends in the dominant depositions of animal bone in the phase IA ditch segments at Etton.The ditch segments are numbered 1-14 clockwise from the lower left.

Small pits, mainly from the northern and eastern parts of the interior of the enclosure, had dark, charcoal-stained fillings, many burnt flints, some sherds and well-burnt animal bone; some had an individual item at their top such as a polished stone axe. One possibility is that these represent funerary rites for individuals (Pryor 1998, 354), and deposition in adjacent ditch segments and pits might have been complementary, though the pits cannot be closely tied to the sequence of the ditch. Once again, when examined in detail, the scale of action is intimate and personal, and animals were involved as a fundamental presence.

There is no sense in insisting on uniformity of practice. The scale of the Etton excavation has reinforced the impression of considerable complexity. The phase 1C deposits of animal bone were more continuous and might be seen as having been deposited in the 1C recut as a single larger-scale event, because of their continuous spread along the ditch (Pryor 1998, 358). This was, however, at a time when the layout qua continuous circuit had somewhat degenerated (Pryor 1998, fig. 115), and the detail of individual segments, such as number 10, may not in fact require a single act of deposition. In this instance (Pryor 1998, fig. 39), though not necessarily in all others of this phase, one could as well suggest series of very small token depositions, reduced in scale but maintaining a previously established way of doing things. Something of this kind of practice, though with perhaps a partially shifted emphasis on wild animals and exotic materials, was continued in phase 2 of the enclosure, with earlier and later deposits in pits, both cut into the top of the ditch and in the interior (Pryor 1998, 360). In ditch segment 12 a pit contained remains of two aurochs skulls above a short plank, as well as other animal bone and pottery, while the later pit F385 in the interior held a horse skull and red deer antler (Pryor 1998, figs 49 and 118).

Finally, from the more restricted excavations at Maiden Castle (Sharples 1991), another set of variations is evident. Finds in the primary fills of the inner and outer ditches were very sparse. In a subsequent phase, the outer ditch was infilled with chalk, probably at the same time as a series of ‘middens’ rich in animal bone, sherds and other material were deposited in the inner ditch (Sharples 1991, 253). It has been argued that most of this material was the result of domestic activity, carried out within or otherwise immediately adjacent to the enclosure (Sharples 1991, 254), but it is at least as likely, not least from the placing of remains in lenses in the partially filled ditch (Sharples 1991, 51 and fig. 49), that this was special activity involving gathering, the killing and consumption of animals, and other tasks, in an arena defined as unusual by its layout, associations and earlier history, and once again within a small-scale social setting.

There is no need to force every example into the same mould. At a similar date across the Channel in northern France at Boury-en-Vexin, Oise, for example, an impressive and concentrated array of cattle and sheep bone may speak for conspicuous consumption on a considerable scale (Meniel 1984; 1987). There, as well as ditch segments with animal bone in more familiar kinds of deposit, there was one segment with a concentration of cattle joints and some near-complete skeletons, as well as sheep joints and partial skeletons. It is also easy artificially to separate the enclosures from other activity in surrounding landscapes. The acts of slaughter and consumption represented in the isolated Coneybury pit near Stonehenge, for example, involving a few cattle and roe deer (Maltby 1990), might not have been greatly different in kind from those seen in enclosures; the chain of connection is seen in this example in the partial representation of carcasses destined for use elsewhere. I have referred in this discussion to the separate headings of household settings and public arenas, but the two may in fact have been partly interchangeable. In the southern British case, as already noted, the evidence for buildings remains equivocal and regionally patchy (Darvill 1996); there are also good arguments for seeing many of such larger buildings as have been found as belonging to the early part of the Neolithic sequence (A. Barclay 2000). In Ireland, the number of quite substantial rectangular buildings from the early part of the sequence continues to increase (Cooney 2000). Here there were varied contemporary monuments, though not in all areas, and the ‘house’ may have been only one of a series of arenas or settings in which important social interaction was transacted.

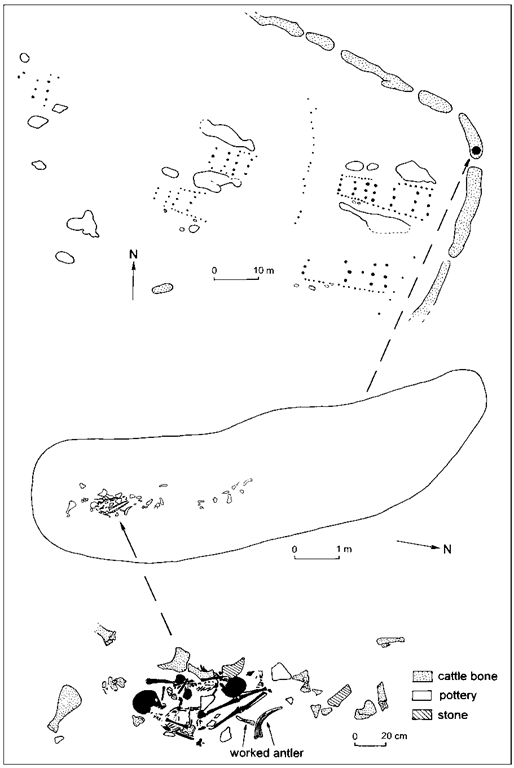

It is easy too to separate enclosures of the kind discussed above from the earlier tradition of longhouse life. While many of the known LBK enclosures belong to the late phases of the culture, and in the case of Langweiler 8 on the Aldenhovener Platte the enclosure seems to formalise the space between longhouses and then take this over as longhouses lapsed (Luning and Stehli 1994), there are now other examples where enclosure and longhouses were more clearly contemporary. Vaihingen in south-west Germany is a case in point, the history of the ditch overlapping that of the longhouses; each share in the history of the site, notably here linked by the presence of human burials in the ditch, in pits and graves alongside it, and in the ditches or pits flanking longhouses (Krause 1997). There is so far little published information on the animal remains from Vaihingen. At Menneville in the Aisne valley in northern France a large oval enclosure formed by a single-circuit ditch with individual segments of varying length surrounded a late LBK settlement with houses; the chronological relationship between enclosure and houses remains uncertain (Hachem et al. 1998). Some houses were close to the ditch, and most of the ditch segments contained little ‘domestic waste’. It is possible that the enclosure came after the settlement had been abandoned, or fell in phases of disuse. The settlement is notable for a number of burials, alongside buildings. There were also burials in some ditch segments, and outside its south-east edge, corresponding to a gap in the enclosure ditch (Hachem et al. 1998, fig. 4). The latter were adult and child burials, while those inside the settlement were mainly children. These contained normal grave goods in the form of ornaments and artefacts, including pots. Burials in the ditch were slightly different. Single burials had ochre and ornaments, but no pottery; one had a cattle horn core and rib. Three multiple burials contained the remains of children only. Their remains were in considerable disarray and there were no ornaments, ochre or complete pots (though there were sherds). Animal bone was, however, much more prominent. In segment 273, the remains of a minimum of four cattle and four sheep/goats accompanied two children (Figure 4.5). In segment 189, a double child burial followed a single one, and cattle and sheep/goat bones are again present. In segment 188, the partial remains of seven children are found in three groups, possibly deposited at the same time, and again accompanied by cattle and sheep/goat bones. Unlike in the settlement contexts of the region, the animal bone was far less fragmented. At a later stage in the ditch fills of segments 188 and 189 more or less above the earlier burials were found cattle skulls, probable commemorative deposits (Hachem et al. 1998, 136). In this case it is plausible enough that the main visible activity was funerary ceremony of some kind (Hachem et al. 1998, 138), but these were not quite of the regular kind. In the absence of a detailed site chronology it is unwise to be dogmatic, but the setting seems to provide already, contemporary with or just after the end of longhouse settlement, many of the themes which continue in later enclosures of the kind already discussed. There are familiar contrasts, such as between the more open and extensive setting of the ditch circuit and the individual longhouses which it contained or commemorated, or between the scale of the ditch circuit as a whole and the more intimate depositional events in individual segments. It is no surprise at all that animals should take their place alongside children in this context as contrasting symbols of fertility and the future, commonality and shared pasts, and abundance and the concerns of particular social groupings.

Figure 4.5 Remains of children (in black), cattle bone and other depositions in ditch segment 273 of the late LBK enclosure at Menneville, northern France.