Thebes, Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings, called in Arabic the Wadi el-Biban el-Muluk (Valley of the Gates of the Kings), and in ancient Egyptian, "The Great, Noble Necropolis of Millions of Years of Pharaoh," or, more simply, "The Great Place," was the burial place of pharaohs and many others in Egypt’s New Kingdom (18th-20th Dynasties). The Valley of the Kings lies on the west bank of the Nile (25°45′ N, 32°36′ E), across from modern Luxor. There are many valleys (wadis in Arabic) in the rugged Theban hills adjacent to the Nile, and there are several reasons why the Valley of the Kings was selected from among them as the site of the royal burials. Three reasons are geographical:

1 a stratum of particularly fine limestone, into which the tombs could be hewn, is exposed there;

2 the wadi is less than 1km from the Nile Valley, where the mortuary temples (which, together with the tombs, form the principal parts of a royal funerary complex) are located;

3 the wadi is easily guarded because of the sheer cliffs and high hills that surround it. Two further reasons are religious:

4 the goddess Hathor, who was closely allied with ideas of rejuvenation, was associated with the Theban landscape;

5 the Qurn, a mountain that rises above the wadi, and which has given its name to the entire area (Qurna), appears from the Valley of the Kings, and only from there, to have the shape of a pyramid, a form long associated with the god Re.

Actually, there are two Valleys of the Kings: the West Valley (WV), which is by far the larger of the two, in which were cut at least three royal tombs; and, immediately beside it, the much smaller East Valley (KV), in which over sixty tomb entrances were dug. The East Valley is the better known of the two.

During the New Kingdom, the Valley of the Kings was considered a sacred precinct, regularly guarded and, presumably, off limits to all but certain priests and officials and the royal family. After it ceased to be used for royal burials, after the end of the 20th Dynasty, tourists came to the Valley frequently. Graffiti left by post-Dynastic visitors, especially by Graeco-Roman travelers, are found throughout the Valley of the Kings and on the walls of fourteen or so tombs or parts of tombs that were accessible then. Such visits continued well into the seventh century AD, when Coptic Christians visited the Valley of the Kings and used several tombs as hermitages or churches. After the Arab invasion of Upper Egypt, such visits apparently stopped; no later graffiti have been found dating before 1739, when the first European visitors left their mark. By the nineteenth century, the Valley of the Kings had become a required stop on every European’s Nile tour, and today nearly a million persons visit it annually.

Not everyone who visited merely looked. Tomb robbery in the Valley of the Kings is attested as early as the New Kingdom; we have ancient transcripts of the interrogations and trials of thieves who broke in almost as soon as a tomb was sealed. The thieves seem usually to have taken objects whose source could be disguised—metals, unguents, perfumes or oils, for example—which could be melted down or repackaged and easily disposed of. In the 20th Dynasty, such looting may have been sanctioned by various governmental and priestly officials anxious to replenish their dwindling economic resources while ostensibly opening tombs in order to rewrap and safeguard royal mummies.

Illicit digging has continued—fortunately with much less frequency—into recent times. During the nineteenth century, even while scenes in some tombs were being recorded by Jean-Frangois Champollion, Richard Lepsius and other early Egyptologists, tomb robbing was occurring nearby. Artifacts from the Valley of the Kings are occasionally still found on the international market.

The KV tomb numbers used today are part of a system established by Sir John Gardner Wilkinson in 1827. At that time, twenty-one tombs were known in the Valley of the Kings, and Wilkinson numbered them in geographical order, north to south and west to east. Since then, many other tombs have been found in both the East and West Valleys: numbering has now reached 62, plus an additional 20 pits and unfinished shafts which have been given letter designations (KV A through KV T). Numbers from 22 onward have been assigned to tombs more or less in order of discovery, KV 62 (Tutankhamen’s tomb) being the most recent.

The first clearing and recording of a whole tomb for which there is contemporary data was undertaken in 1816 by Giovanni Belzoni and his sponsor, Henry Salt; they opened Tombs 16, 17, 19, 21, 23 and 25. Belzoni’s discovery of KV 17 (the huge and spectacularly decorated tomb of Seti I) made the Valley of the Kings one of the world’s best known archaeological sites, and copies of its scenes and inscriptions, which Belzoni exhibited in London, greatly stimulated European interest.

Sixty-seven years later, in 1883, Egyptologist Eugene Lefebure began copying inscriptions in KV tombs. In 1898, Victor Loret, Director of the French-controlled Egyptian Antiquities Service, began the clearing of KV 33-8. (It was Loret who discovered, in KV 35, one of the two caches of royal mummies hidden by 20th Dynasty priests.) Lefebure’s copies were not precise facsimiles, and Loret’s clearing was little more than hacking through stratified sand and rubble in search of doors and pits. But both kept notes, both published their results, and their work is considered by some to mark the beginning of modern research in the Valley.

The most extensive archaeological work in the Valley of the Kings was that conducted by the English archaeologist Howard Carter. His work there had begun in 1900 when, as an Inspector of Antiquities, he supervised the introduction of electricity. Carter first excavated in the Valley in 1902 (working on a project of the American millionaire Theodore Davis), and continued to dig (supported after 1907 by Lord Carnarvon) until 1922, when he discovered KV 62, Tutankhamen’s tomb.

None of the work done in the Valley of the Kings prior to the 1970s involved much more than moving debris in search of artifacts. There were only a few exceptions: among these, Alexandre Piankoff’s epigraphic work stands out. Since the 1970s, however, more controlled fieldwork has been undertaken, including the epigraphic work of Eric Hornung, the geological studies of the Brooklyn Museum, and the mapping, stratigraphic excavation and conservation projects of the Theban Mapping Project of the American University in Cairo. All of these have been guided by the masterful history of the Valley of the Kings published by Elizabeth Thomas.

The first pharaoh to have been buried in the Valley of the Kings seems to have been Tuthmose I. An official in his court, Ineni, claimed to have supervised digging his tomb. Some have argued that this tomb was KV 38; more likely, it was KV 20, later usurped by Queen Hatshepsut. Even today, there is disagreement about the correct attribution of some tombs. Egyptologists believe that every New Kingdom pharaoh from Tuthmose I to Ramesses XI began work on at least one tomb in the Valley. But neither the texts in these tombs nor the elements of their design always guarantee certain knowledge of the owner. A great deal is known, however, about how tombs were carved and decorated, thanks to the vast number of documents found at Deir el-Medina, the New Kingdom village in which lived the quarrymen and artisans responsible for their cutting and painting. We are also beginning to understand more fully the reasons for the tombs’ frequently changing plans. These changes reflect evolving theological views of a king’s journey to the afterlife, but they also indicate that rulers sought to outdo their predecessors in the size of their burial place. From one New Kingdom pharaoh to the next, doors and corridors usually become wider, chambers larger and more numerous.

Royal tombs may be arranged roughly into three categories according to their plan. Type 1 tombs have a corridor (sometimes level, sometimes sloping, sometimes with stairs) that often turns to the right. These are tombs of the 18th Dynasty, with entrances cut at the base of steep cliffs. Type 2 tombs are similar, but often turn to the left. Their plan sometimes jogs just beyond a shaft now thought to represent the burial place of Osiris (rather than simply being a precaution against thieves or floods). Their entrances are dug in a variety of topographical positions. They date from the 18th and 19th Dynasties.

Tombs Egyptologists call Type 3 were called by the Greeks "syringes," meaning "shepherd’s pipes," and their long succession of corridors and chambers, sometimes descending deep into bedrock, do indeed look like long rectangular tubes. These tombs are of the 19th and 20th Dynasties. Their entrances lie at the bottom of sloping hillsides.

The following list includes royal (or thought to be royal) tombs, plus a few others of special interest. (Most of the tombs omitted from this list are little more than small, crudely cut, single chambers or unfinished pits, or tombs "lost" in modern times.)

KV 1, Ramesses VII: Type 3, 40m long; open since antiquity.

KV 2, Ramesses IV: Type 3, 66m long; an ancient plan of this tomb is found on a papyrus now in Turin; never completely cleared, but accessible in Graeco-Roman times.

KV 3, a son of Ramesses III: non-royal, 37m long; cleared by Harry Burton (1912).

KV 4, Ramesses XI: Type 3, 93m long; open since antiquity, cleared by the Brooklyn Museum expedition (1979).

KV 5, originally a late 18th Dynasty tomb, reused by Ramesses II for at least three of his sons: largely inaccessible since then; unique, complex plan; clearance by the Theban Mapping Project began in 1989.

KV 6, Ramesses IX: Type 3, 86m long; open since antiquity, cleared by Georges Daressy (1888).

KV 7, Ramesses II: Type 3, over 100m long; one of KV’s largest tombs, partly dug in 1913, but still largely uncleared.

KV 8, Merenptah and perhaps Isinefret, his wife: Type 3, 115m long; open since antiquity, dug by Howard Carter (1903).

KV 9, double tomb of Ramesses V and Ramesses VI: Type 3, 104m long; open since antiquity, cleared by Daressy (1898).

KV 10, Amenmesse and family members: Type 3; open since antiquity, currently being cleared.

KV 11, Sethnakhte, completed by Ramesses III: Type 3, 125m long; open in antiquity, but never fully cleared.

KV 13, perhaps tomb of Bay (under Tawosret): seriously damaged by flooding in 1994.

KV 14, Tawosret and her husband Seti II, then usurped by Sethnakhte: Type 3, 110m long; some digging in 1909.

KV 15, Seti II: Type 3, 72m long; perhaps the digging of this tomb was started, abandoned, then hastily resumed but never completed; open in antiquity, cleared in modern times.

KV 16, Ramesses I: 29m long; dug by Giovanni Belzoni (1817).

KV 17, Seti I: Type 2, one of the largest and longest KV tombs (over 230m, including an enigmatic passageway extending 90m beyond the burial chamber); dug by Belzoni (1817).

KV 18, Ramesses X: never cleared.

KV 19: Mentuherkhepshef, a son of Ra-messes IX, was perhaps hastily buried in this hardly begun (20m long) and never finished tomb; found by Belzoni, cleared by Edward Ayrton (1905).

KV 20, Tuthmose I: Type 1, 200m long; perhaps the first tomb dug in the Valley of the Kings, later usurped and enlarged by Hatshepshut; first dug by James Burton (1824), later by Carter (1903).

WV 22, begun by Tuthmose IV, the tomb was used by Amenhotep III (but probably not by others of his family): Type 1, 100m long; discovered in 1799, cleared by Carter in 1915.

WV 23, Ay: 55m long; discovered by Belzoni (1816), but not cleared until 1972.

WV 25, possibly begun for Amenhotep IV, although Tuthmose IV or one of his sons, Amenhotep III, Smenkhkare or Tutankhamen have also been suggested: unfinished; found by Belzoni (1817) and only recently cleared.

KV 34, Tuthmose III: Type 1, 55m long; cleared by Loret (1898).

KV 35, Amenhotep II: Type 1, 60m long; reused as one of the two caches in which priests of the 20th Dynasty reburied royal mummies; opened by Loret in 1898.

KV 38, perhaps dug by Tuthmose III for the re-burial of Tuthmose I (moved from KV 20): Type 1; cleared by Loret (1899).

KV 42, perhaps intended for Hatshepsut, but never used by her; may have been used by the mayor of Thebes, Sennefer, and his family: Type 1; cleared by Carter (1900).

KV 43, Tuthmose IV: Type 1, 90m long; cleared by Carter (1903).

KV 46, Yuya and Tuya, parents of Amenhotep III’s wife, Tiye: they were buried at different times (Yuya first), and shortly after the last interment the tomb was plundered of valuable items, later robbed again, resealed in the reign of Ramesses III, robbed yet again and finally resealed by Ramesses XI; when found by Theodore Davis (1905), it still contained numerous artifacts.

KV 47, Siptah and his mother: Type 3, 89m long; dug by Ayrton (1905), Harry Burton (1912) and Carter (1922).

KV 54, a small pit, in which embalming materials of Tutankhamen were buried: opened in 1907.

KV 55, this small unfinished tomb is late 18th Dynasty, but its attribution (to Tiye or Akhenaten or Smenkhkare) and true purpose remain hotly debated: cleared by Ayrton for Davis (1907).

KV 57, Horemheb: Type 2, 114m long; elegant examples of wall decoration in various stages of completion; dug by Ayrton for Davis (1908).

KV 62, Tutankhamen: the most famous (and most carefully recorded) tomb in the Valley of the Kings; twice robbed, but nevertheless found almost perfectly intact by Carter in November, 1922; still largely unpublished.

Thebes, Valley of the Kings, Tomb KV 5

In 1800, savants accompanying Napoleon Bonaparte’s expedition to Egypt prepared a map of the Valley of the Kings and noted the presence of a tomb entrance at the head of the path leading into the Valley. During the nineteenth century, several other visitors acknowledged the presence of this tomb entrance on sketch plans or in their notes, but only Richard Burton, in 1825, attempted to breech the rubble-filled door and explore the tomb’s interior. Burton dug a narrow channel through the fill in the first three debris-choked chambers, but, able to see only the ceiling of the tomb and none of its walls, he decided that the tomb was undecorated and of no importance. Similarly, early in the twentieth century, Howard Carter’s workmen dug through the first 50cm of debris at the tomb’s entrance, then abandoned their work, convinced that the tomb was simply a small, undecorated pit. Carter’s men proceeded to use the hillside above the tomb entrance as a dumping ground for debris from their other excavations. This tomb is called KV 5, the number given it on the survey of John Gardner Wilkinson (1827), and it has lain since Carter’s days hidden beneath several meters of rubble.

In 1987, the Theban Mapping Project (TMP) sought to relocate KV 5. The general area in which it was believed to lie was to be cleared by the Egyptian Antiquities Organization (EAO) to create a large bus park and the TMP wanted to prevent that work from doing any inadvertent damage to the tomb. After only a few weeks of work, KV 5′s entrance was found. Over the next seven years, the TMP cleared the tomb’s first two chambers and discovered not only that their walls were extensively decorated, but that there were large quantities of artifacts lying on the chamber floors.

Both artifacts and inscriptions indicated that KV 5 was a tomb used for the burial of several sons of Ramesses II: the names of three sons were found in chamber 1 alone. It was clear that KV 5 could be a tomb of considerable historical interest.

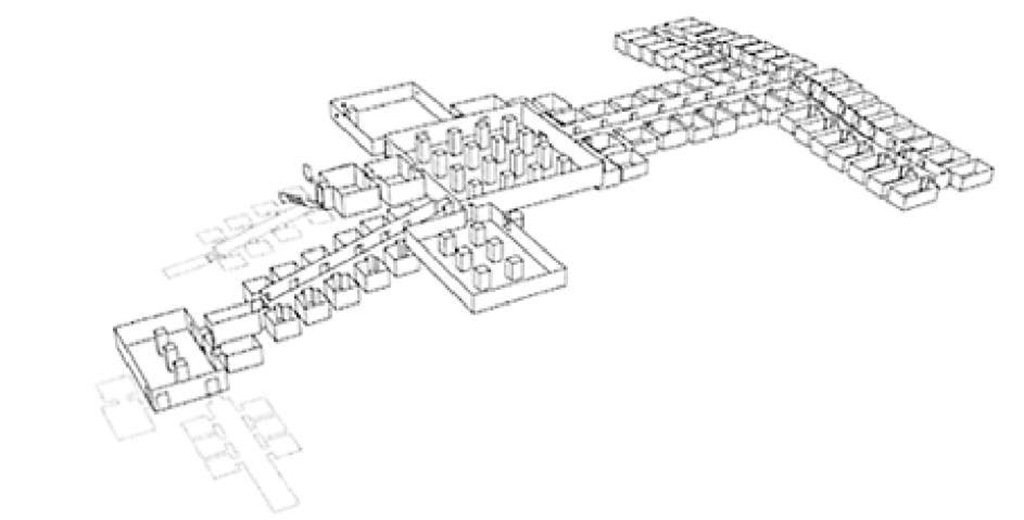

In the spring of 1995, the TMP explored a doorway in the rear wall of chamber 3, a huge sixteen-pillared hall. The doorway was sealed by debris, and it subsequently became clear that no one had gone beyond it in the last 3,000 years. We expected to find that the door led into nothing more than a small chamber. Instead, we found a 30m corridor at the end of which were two 20m transverse corridors. At their junction stood a 1.5m tall statue of Osiris, and in their walls were cut forty-eight doorways leading into 3x3m rooms, or suites of rooms. The walls of both corridors and rooms were decorated in relief or painted plaster and showed scenes of Ramesses II presenting various of his sons to deities in the afterlife.

In the autumn of 1996, two additional corridors were found in the front wall of the sixteen-pillared hall. These lead steeply down at a 35° angle and are also lined with side chambers. Only one of these two corridors has so far been explored—we have dug 20m, exposing twelve rooms—but work has not yet revealed the end of the corridor, or its destination. The walls here are also decorated.

Artifacts from KV 5 include thousands of potsherds, hundreds of pieces of jewelry, scores of red granite, alabaster, basalt, and breccia sarcophagus fragments, broken canopic jars (where the internal organs of a mummy were separately embalmed), servant statuettes (shawabtis), stone statues, wooden coffins, bird and animal bones, and bits of three fragmentary and one nearly complete adult male mummy. This evidence makes it clear that KV 5 was not only intended to be a tomb but was in fact used as the burial place of a number of Ramesses II’s many sons.

The TMP is continuing its work m KV 5 and, given the size of the tomb, work is likely to continue for at least another decade. But it is already possible to make several observations. First, KV 5 is the largest tomb ever found in Egypt. To date, 108 chambers and corridors have been identified. Second, the plan of KV 5 is unique; there are few tombs of any period that bear even a superficial resemblance to it, and few temples that show even remote similarity. Third, KV 5 was the burial place of many of the sons of Ramesses II and was used as such. We have so far found the names of four sons associated with the tomb, but there are at least twenty-five representations of sons on chamber and corridor walls (the accompanying names either missing or not yet cleared of debris). Fourth, KV 5 is unique in Egyptian history: no other family mausoleum has ever been identified. Fifth, the many chambers found so far seem unlikely to have served as the actual burial chambers of the sons (unlikely in part because their narrow doorways could not have accommodated a stone sarcophagus), and we are assuming that the burial chambers lie elsewhere in the tomb, perhaps to be reached via the steeply sloping corridors at the front of the sixteen-pillared hall. If this assumption is correct, then the number of chambers in KV 5 will increase substantially before the TMP completes its clearing.

Figure 123 Plan of Tomb KV5, Valley of the Kings, Thebes