Saqqara, North, Early Dynastic tombs

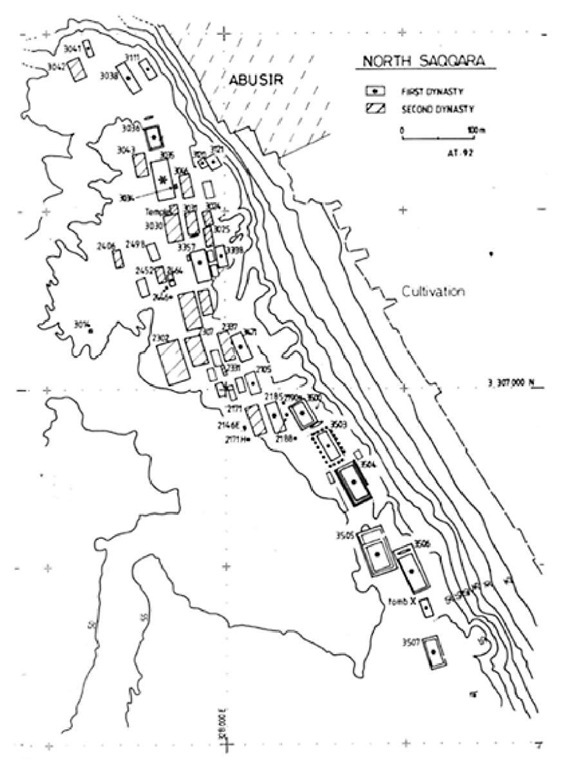

The Saqqara necropolis is situated in the Western Desert approximately 24km south of Cairo and immediately southwest of the modern village of Abusir (29°53′ N, 31°13′ E). The Early Dynastic tombs excavated at Saqqara/Abusir can be divided into three groups: (1) the large 1st and 2nd Dynasty mastaba tombs occupying the eastern edge of the North Saqqara plateau; (2) two areas of smaller tombs in the Abusir Valley; and (3) a series of underground galleries of the 2nd Dynasty (but no surviving superstructures) in the area of the Unas pyramid and pyramid temple (5th Dynasty). Excavations at North Saqqara by English archaeologists J.E. Quibell, C.M.Firth and W.B.Emery have exposed a series of large 1st and 2nd Dynasty tombs along the 55m contour line on the eastern edge of the desert plateau, a location which would have made such structures highly visible from the cultivation.

The 1st Dynasty tombs at North Saqqara are large imposing structures often surrounded by single or double enclosure walls and rows of subsidiary tombs. Various other structures are associated with individual tombs.

Architectural development

Roughly three broad stages of tomb development can be discerned within each Dynasty (early, middle and late). The tomb type of the early 1st Dynasty is well represented by Tomb 3357, dated to the reign of Aha. It consists of a rectangular pit cut in the gravel and rock, subdivided by mudbrick walls into five rooms, with the larger, central one as the burial place. At ground level, a rectangular mudbrick superstructure (called a mastaba) was built. It was subdivided into magazines and had a rubble core. As there is no recognizable method of entry to the burial chamber, it is assumed that the structure was finished after the burial had taken place. The exterior fagade had recessed paneling ("palace fagade") on all four sides. Tomb 3357 had a double enclosure wall (overall measurement 48x22m), but no subsidiary burials. To the north of Tomb 3357 is a series of low buildings described by the excavator as a "model estate." Two of the buildings at the east and west have arched roofs and three rounded structures may represent granaries. To the north of the "estate" a boat grave was excavated.

Another example of the "pre-stairway" tomb type is the large Tomb 3503, attributed to Queen Merneith. It also has an enclosure wall, a boat and twenty subsidiary (human) burials.

The tomb of the official Sekhemka (3504) shows a transitional design. It is also the earliest example of a superstructure surrounded by a low bench on which were placed 300 bulls’ heads modeled in clay and fitted with real horns. Tombs 3507 and 3505, respectively, dating to the reigns of Den and Qa’a, also have this feature.

The mid-1st Dynasty is a period of innovation, with a large number of tombs built at Saqqara during the reign of Den. There is also an increase in size and elaboration of tombs leading to the introduction of the stairway. These are from the east, beginning outside the superstructure and leading directly to the burial chamber. The design of the substructure remained unchanged, although these were cut at a deeper level (earlier tombs were usually cut no deeper than 4m). Tomb 3038 is situated at the northern apex of the plateau and is dated to the time of Anedjib. Originally, it had a rectangular earthen tumulus with mudbrick casing over the burial pit. The tumulus was later changed into a stepped form. Similar tumuli are attested in Tombs 3507, 3111 and 3471. These were considered to be the prototype of Zoser’s Step Pyramid (3rd Dynasty) and later pyramid structures. However, they are more likely to be a device incorporating the early Upper Egyptian tomb type into Saqqara mastaba tombs.

During the late 1st Dynasty, the paneled fagade was abandoned in favor of plain fagades with two "false doors" at the north and south ends of the east wall. The superstructure now has a solid core of rubble or mudbrick and the stairway is L-shaped, starting from the east and entering the burial room from the north. Subsidiary rooms within the substructure are not adjacent to the burial chamber but placed to either side of the stairway. This tomb type is exemplified by Tomb 3338. Tomb 3500 retains the east-west axis of the burial chamber (a north-south axis is more common at this time) and the stairway approach is from the east. This tomb also has the latest subsidiary burials, which differ in form and construction from early examples.

Figure 97 1st and 2nd Dynasty tombs at North Saqqara

The largest Early Dynastic mastaba tomb at North Saqqara is Tomb 3505, dating to the reign of Qa’a. This tomb retained the paneled fagade and had a double enclosure wall and a funerary temple to the north. Access to the burial chamber was via a north-south ramp, which turns and enters the chamber from the east. At the end of the 1st Dynasty the system of open working of the substructure was abandoned. Tombs 3120 and 3121, dating to Qa’a's reign, already have the burial chamber excavated in the bedrock. The superstructure is then as a conventional mudbrick mastaba.

In the early 2nd Dynasty the tomb design of the late 1st Dynasty was retained, but the L-shaped stairs, the magazines and the burial chamber are all rock-cut. Mudbrick walls were used to divide the underground chamber into different rooms, with the burial chamber on the west side. The practice of burying provisions within the superstructure had not quite died out, as is attested by the large amounts of pots found buried in groups within the core of some tombs.

By the mid-2nd Dynasty, the standard tomb design is of the "house" type, where the various rooms are cut separately and may represent the plan of contemporary houses. This is well represented by Tomb 2302, dated to the reign of Nynetjer. Tombs 2307 and 2337 even have areas identified as a bathroom and lavatory. The superstructures are of mudbrick covering a solid core of rubble or liquid mud, and the plain fagade has two false doors. At the close of the 2nd Dynasty examples of shaft tombs of the "dummy-stairway" type appear at North Saqqara.

Although the area was systematically excavated between 1910 and 1959, some of the results have not been fully published. For example, built against the north enclosure wall of Tomb 3505 is a semicircular or horseshoe-shaped, whitewashed mudbrick wall, of unknown purpose.

At North Saqqara some new tomb features appear during the reign of Qa’a, including a funerary temple to the north of Tomb 3505, and statue niches in Tombs 3120 and 3121. A transitional design is found later in Tomb 2464, and, dating to the end of the 2nd Dynasty, Tomb 2407 has a statue annex which, together with the temple to the north of Tomb 3030, shows a close resemblance in plan to the temple of 3505.

Boat graves from the time of Aha to Den have been excavated at Saqqara. Each was on an east-west axis roughly parallel to the north side of their associated mastaba. The boat grave of Tomb 3506 is placed within an enclosure wall, immediately north of the mastaba, while the boat grave of Tomb 3357 was over 25m to the north of the model estate. The boats of Tombs 3357 and 3036 were sunk below ground level, then lined with mudbrick and plastered, while those of Tombs 3503 and 3506 had the mudbrick superstructure built directly on the desert surface. The excavator noted that all showed signs of the enclosure wall having been built after the boat was in position. Unlike examples at Helwan, where hardly any traces of the superstructures survive, the Saqqara boat graves were preserved up to 1m high. Traces of wood, rope and pottery were found in situ.

Topographic distribution

A pattern can be seen in the distribution of large 1st Dynasty tombs on the Saqqara escarpment: the earliest tomb (3357), dated to AhaVeign, has a prominent and central position, near an indentation in the escarpment, which probably served as an access route to the plateau. Mastabas dated to the reigns of Djer and Djet spread southward from Tomb 3357. During the reign of Den tombs continued to spread south along the escarpment edge, as well as north from Tomb 3357. This development in both directions continued until the end of the dynasty. The large mastabas of the 2nd Dynasty were generally built behind those of the 1st Dynasty, also following the alignment of the escarpment. Again, the area around Tomb 3357 functions as a focal point with tombs dated to the reign of Nynetjer spreading north and south from a point just behind it (i.e. to the west). At present, the southern limit of the necropolis is unknown: the large tombs extend for approximately 300m along the escarpment edge, and were generally assumed to end in the south at Tomb 3507. However, traces of an Early Dynastic structure, almost certainly a tomb, have been found during excavations halfway down the rock face in the Anubieion temple area and in 1987 the niched northern fagade of an early 1st Dynasty mastaba was exposed during construction of a water tower immediately north of the Egyptian Antiquities Organization Inspectorate office.

The North Saqqara cemeteries show an absence of medium-sized tombs of the 1st Dynasty: the escarpment was dominated by large mastaba tombs and their subsidiary burials, with the much smaller tombs in the cemeteries of the Abusir Wadi. A different pattern of use seems to emerge during the 2nd Dynasty, with greater variety in tomb sizes, including very small burials, more intensive use of space, with small tombs wedged between larger ones, and spreading further toward the eastern edge. This is evident in the area south-southeast of Tomb 2302, and to the north and east of Tomb 3038, where Emery excavated various small 2nd Dynasty tombs.

The early tombs at North Saqqara follow the line of the escarpment, with the axis on a northwest-southeast alignment, in contrast to the alignment of the long axes of most 3rd Dynasty mastabas, which are only a few degrees off true north. The position of the Early Dynastic tombs is clearly related to the topography of the Saqqara plateau. Unlike mastabas of the 3rd Dynasty, which have a fairly consistent line of approach, earlier tombs show greater variation, although there is a general preference for an east-facing approach. Tomb 3505 has the entrance to its superstructure at the north end of the east wall. This, however, is related to the position of the funerary temple and the fact that access farther south was hampered by the proximity of Tomb 3506. Tomb 3500, although retaining a niche on the east wall and access to the substructure from the east, has an entrance at the southwest of the enclosure wall. This unconventional arrangement is perhaps due to the proximity to the desert edge and the fact that the boat grave of Tomb 3503 was just to the south, limiting access even further. Access to Tomb 3038 was via north and south stairways, which relate to the unusual tomb design.

Royal or private cemetery?

Current research suggests that North Saqqara was a private cemetery during the Early Dynastic period, and not a royal one. Evidence for this is based on the following:

1 The small size of Saqqara tombs when compared with the "funerary enclosures" at Abydos.

2 The number, size and absence of stelae in subsidiary burials at Saqqara.

3 The attribution of more than one mastaba per king at Saqqara.

4 Lack of differentiation in layout or location between presumed "royal" tombs and other mastabas at North Saqqara. Size alone is not sufficient evidence for royal attribution.

5 The presence of tumuli within the superstructures of some Saqqara tombs is not an indication of royal ownership but an attempt to incorporate the early Upper Egyptian tomb type within these Saqqara mastabas.

6 The funerary temple of Tomb 3505 is not a royal feature but does fit into evidence of private tomb development.

7 The mix of large and small tombs and the reuse of the area from the early 2nd Dynasty suggest that this is unlikely to be a royal site.

8 Royal and private cemeteries remain quite distinctive at Saqqara until the 5th Dynasty.

As the main cemetery for the newly founded capital, the North Saqqara cemetery is also crucial in providing an indication of the where-abouts of Early Dynastic Memphis.

Saqqara, pyramids of the 3rd Dynasty

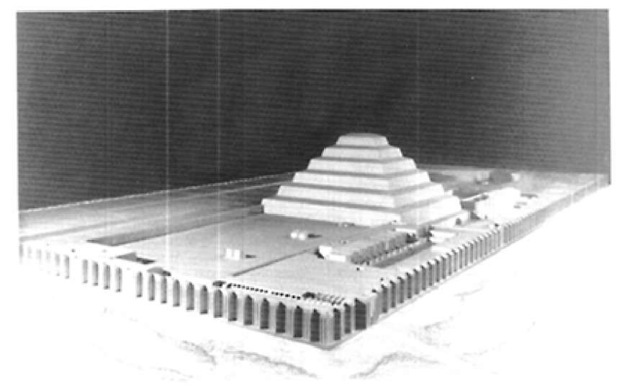

On the west bank of the Nile on the edge of the desert at Saqqara (29°50′ N, 31°13′ E) is the Step Pyramid complex of Horus Neterikhet, known as King Zoser (or Djoser), probably the second pharaoh of the 3rd Dynasty. The buildings of the complex are remarkable because they are the first ones made of quarried stone, in regular courses.

The third century BC historian Manetho confirms the Zoser complex’s originality when he reports that Imhotep, whom the Greeks called "Asclepios" for his medical talents, invented the art of stone masonry during the reign of Tosorthros (Zoser). Excavation of the colonnade at the enclosure’s entrance led to the discovery of one of the statues of the king, on which are engraved the names "Horus Neter-ikhet" and "Imhotep," with the titles "Chancellor of the King of Lower Egypt, first under the King of Upper Egypt, administrator of the grand palace, noble heir, high priest of Heliopolis, Imhotep, the builder, the sculptor"

The first modern exploration of the Step Pyramid was made by the Prussian general Baron von Minutoli, who entered it with the Italian engineer Geronimo Segato in 1821. They discovered two chambers, decorated with blue faience panels, and the granite vault, which had already been plundered in antiquity. In the corner of a hallway they found what was left of a mummy with a heavily gilded skull and a pair of sandals, also gilded. These were removed by von Minutoli, but then lost at sea.

In 1924, Pierre Lacau and Cecil M.Firth began excavating the complex. The first places they explored were two mounds, situated at the northeast corner of the main pyramid. They were greatly surprised to find two fagades with fluted columns almost in the Greek Doric style. Firth at first thought he was excavating a Ptolemaic structure, but some New Kingdom hieratic writing on the walls of the entrance corridors soon proved the building to date to the 3rd Dynasty. It was in these inscriptions that the name "Zoser" was first found; contemporary texts all use the name "Neterikhet," sometimes followed by the epithet "golden sun."

Figure 98 Model of Zoser’s Step Pyramid complex at Saqqara

During study for the restoration of the structure, it was recognized that the design of a wooden building was reproduced in stone. The fagade is composed of fluted, slender columns, up to 12m high and in the shape of pine tree trunks. These columns, together with perpendicular beams, appear to support an arched roof modeled after the reed structures of the festival pavilions and primitive sanctuaries that are represented by the hieroglyph "If.

Firth discovered the enclosure’s only entrance, a narrow passage (1.05m wide and 6m long) cut into the outer wall’s most prominent niching. Only the first two or three courses of the wall remained, but the original size can be reconstructed. The entrance leads to a second, wider passage and a magnificent corridor of forty columns, in a previously unknown style of reeds. These once supported a heavy ceiling made of stone blocks, which were rounded below to represent logs of palm trees trunks. Each column is engaged to a protruding wall, perpendicular to the direction of the corridor. These walls are intended both as a supplementary, strengthening precaution, and as a means to compensate for the excessive segmentation of the columns.

Near the middle of the colonnade a passage leads to a small sanctuary, which must have contained Zoser’s statue and its pedestal, inscribed with the king’s name and Imhotep’s titles. The passage opens on its west side into a perpendicular room, its ceiling supported by eight columns. It has been possible to restore these columns to their original height, using many of the original stones.

Beyond the colonnade is a vast open space bounded on the north by the pyramid and on the other three sides by mounds of rock with a few vestiges of what once was a magnificent paneled wall of fine Tura limestone. In the southwest corner is a sanctuary that must have been Zoser’s second tomb, a kind of cenotaph built at the base of the south wall, with a frieze of uraei (sacred cobras) at the top. Several meters of this wall have been restored.

At the north end of the large court is a structure shaped like a pair of D. A twin structure facing in the other direction, 55m farther south, has almost disappeared. These were markers staking out a course for the king’s ka to run symbolically the races of the teh-wd (jubilee) festival. About 50m north of the better preserved double-D is an altar with an access ramp, almost touching the base of the pyramid. To the east a false door opens into the rest house of the king’s ka, the waiting place for the heb-sed ceremony of the afterlife, which is depicted in the complex. Beyond this is the sanctuary where the king’s statue must have been situated in the central niche, flanked by two others, above which are lintels decorated with symbols of rebirth (djed pillars). A few meters to the south, and then east, following an unusual, curved wall, is the heb-sed court.

All the main deities have sanctuaries in the heb-sed court, along 80m of the west and east walls, and north of the king’s dais. On the better preserved west side, chapels of two types have been reconstituted: the first has torus molding along the external corners, and a horizontal roof, with a slight overhang that suggests the later cavetto cornice. The other type has narrow, decorative, fluted columns, placed on pedestals more than 2m high and topped by capitals with fluted leaves, which support an arched roof. Two restored chapels have stairways of inclined steps leading to a very large niche, which probably held a larger than life-size statue of Zoser, a few fragments of which were found. The chamber with a horizontal roof in the southwest corner of the court has been restored to its original size.

On the east side of the heb-sed court is a row of twelve chapels with vaulted roofs, narrower than the others and without columns. Two of them have been restored, partly with original blocks,. To the south of these chapels fragments of three caryatid statues of King Zoser were found on the ground. All of these chapels are accessible from the court through roofless, zigzagging corridors, formed by low walls four cubits high. A small niche with a vaulted roof is the only accessible chamber in these chapels; the main edifice is solid stone.

Leaving the -’^"^court by the north side, one comes to the base of a pavilion with torus moldings. Inside it are the surviving feet of four statues, two of adults and two of children. They are probably from statues of Zoser, as King of Upper and Lower Egypt, and the two king’s daughters, Hetephernebti and Inkaes.

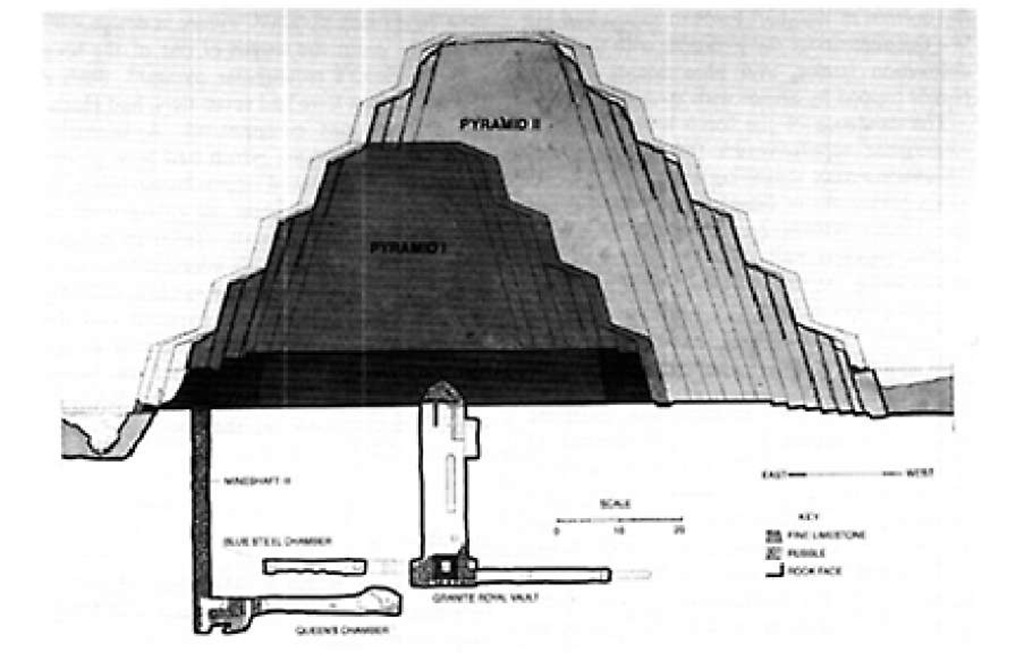

The pyramid was first designed as a mastaba (M1), a long low superstructure that was later expanded in two stages (M2, M3). Only in its fourth and fifth building stages was it enlarged to a stepped form.

Along the east face of the original mastaba are eleven shafts, about 30m deep, for members of the royal family. At the entrance of one shaft thick logs are still preserved which once helped to lower the alabaster sarcophagus, funerary equipment and furniture, and the coffin of an eight year-old child. At the same location what is left of the casings of three structures can be seen: the third and latest mastaba (M3), the first, four-step pyramid (P1), and the second, six-step one (P2). At the northeast corner of mastaba M3 the horizontally laid stones of mastaba M3 and stones of pyramid P1, with courses sloping down inward, can both be seen.

Along the east side of the Step Pyramid are the two "Houses of the South and North," where the king’s ka was meant to receive delegations from Upper and Lower Egypt. Columns with lily capitals (identifying the South building) and papyrus capitals (for the North one) once decorated the walls.

Around the northeast corner of the pyramid, one comes to the statue chamber (serdab), which lies directly against the pyramid. This chamber contained the remarkable painted limestone statue of Zoser that is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. In its place in the serdab is a replica that can be viewed through two cylindrical holes, which allowed the ka statue to receive incense smoke from the mortuary temple.

Immediately to the west of the serdab is the east wall of the mortuary temple, preserved to a height of approximately 2m, which meets the north side of the pyramid. Through the temple’s entrance is a corridor which turns around the temple, and ends at two rectangular inner courts. These are bounded on the pyramid side by a portico of four fluted columns, engaged in the corners of two rectangular pillars. Remains of two rooms with basins and water channels were found here. Beyond several rectangular chambers is space for a statue facing the pyramid, and another space, probably for an offering table perhaps flanked by two stelae, as at Meydum.

SUCCESSIVE STAGES OF THE PYRAMID

Figure 99 Cross-section of Zoser’s Step Pyramid at Saqqara, showing the different stages of construction

Finally, in the western porticoed court, is the entrance of the descending gallery to the king’s granite vault, where one of Zoser’s feet was found, mummified in the Old Kingdom manner. The shaft also gives access to some adjoining galleries and storerooms, and to the chambers reserved for the king’s ka. Two of these, containing blue faience, were already known when Firth and Lauer found two new ones: one with three false door stelae depicting the king, the other with three panels of blue faience topped by ornamental arcades of djed pillars. There were also fragments of a fourth panel, which has been rebuilt by Lauer in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Inside the south enclosure, near the "wall of uraei," is the great shaft of the so-called South Tomb, of the same size as the one in the pyramid (7m on a side and 28m deep). The granite vault at the bottom of this shaft is in the same style as the pyramid’s, but smaller, and square (approximately 1.60m on a side) instead of rectangular. Except for a part of the granite plug, nothing was left in this section of the tomb when, in 1927, Firth and Lauer became the first persons to enter it since the tomb robbers, 4,000 years before. Toward the east, the bottom of the shaft leads to rooms laid out like the ones under the pyramid, with the same decoration (stelae, and blue faience tiles in panels topped by arches with djed pillars).

The existence of the tomb is marked by a rectangular superstructure (84x12m), with transverse arches indicating a roof. On this roof was a casing of fine limestone, of which only a few blocks remain on the south face. The outside paneled wall is particularly well preserved along the length of the tomb, still rising in some places as high as 4.80m.

Another superstructure, similar, but twice as wide and 400m long, occupies a large part of the complex’s west terrace. Beneath it are two very long, shallow, subterranean galleries, which give access to a large number of rectangular chambers. The extremely bad condition of the rock prevented Firth from excavating these chambers. Numerous fragments of 3rd Dynasty stone vases were found at the south end. The clay from here was used as mortar for the pyramid and the complex’s other large masses of masonry. According to Firth, the presence in this area of hard-stone plates and dishes indicates the presence nearby of secondary tombs.

Finally, in the obviously unfinished northern part of the complex, there is a gigantic altar carved into the rock, with the remains of a limestone casing. Offerings must have been exposed on the altar before being taken, through a shaft 60m away, down into storerooms that branch from a gallery running east-west. These chambers contained mostly wheat and barley, as well as sycamore figs, bunches of grapes and what were probably loaves of bread. Above the passageway, the mass of rock against the outer wall is oddly divided into rectangular chambers, each one having two outside openings one above the other, as in granaries. They apparently represent storehouses.

Tomb complex of Horus Sekhemkhet

Horus Sekhemkhet, probably the son of Zoser (or Horus Neterikhet), seems to have been Zoser’s immediate successor. He planned an even bigger step pyramid, square in design with each side about the length of one of the long sides of Zoser’s rectangular pyramid. Such a pyramid might have had seven tiers, had Horus Sekhemkhet not disappeared. A beautiful alabaster sarcophagus, which had been placed there for him, remained empty. Nevertheless, he had enough time to begin the enlargement of the paneled enclosure wall, similar in appearance to Zoser’s but initially intended to cover a much smaller area. A planned mastaba was only partially built, between the pyramid and the first wall on the south side. Like that of the pyramid, its underground chamber was barely begun and was used, no doubt after Sekhemkhet’s disappearance, as the tomb of a two-year-old child.