Mummification

Examples of mummification (where bodies are preserved by either natural or artificial means) are found in a number of countries, but the ancient Egyptians produced the most advanced techniques and the best results. The word "mummy" may be derived from the Persian or Arabic word mumia meaning "pitch" or "bitumen," and was probably originally applied to the artificially preserved bodies of the ancient Egyptians because of their "bituminous" appearance.

In the earliest burials in Egypt from the Predynastic period (circa 4,500-3,050 BC), human remains (consisting of the skeleton and remaining body tissue) were preserved by natural circumstances. The bodies were interred in shallow pit-graves on the desert edge, and the combination of the sun’s heat and the dry sand desiccated the body tissues before decomposition set in. The result was a remarkable degree of natural preservation of these bodies, which frequently retained substantial amounts of skin, tissue and hair.

However, when more sophisticated tombs were introduced for the elite in late Predynastic times (circa 3,400 BC), with underground, bricklined burial chambers, the bodies, no longer buried in the sand, rapidly decomposed. Nevertheless, well-established religious beliefs demanded that the body should be preserved so that the spirit of the deceased would be able to recognize and take possession of it, in order to obtain nourishment through the body from the food offerings placed at the tomb. A period of experimentation followed, with attempts to find a method of retaining the physical likeness of the deceased and of preserving the body using artificial means. Such methods were unsuccessful, however, because they did not arrest the decay in the body tissues, which continued to deteriorate and disintegrate beneath the linen bandages wrapped around the body. Instead, emphasis was placed on the outward appearance of these "mummies," with the body being encased in resin-soaked linen, which was carefully molded to retain the shape, and details of the face and genitalia were painted on the outermost linen covering.

True (or artificial) mummification, which can be defined as an intentional method of preservation involving various techniques, including the use of chemical and other agents, was already in use at the beginning of the 4th Dynasty. In the burial of Queen Hetepheres (the mother of King Khufu) at Giza, visceral packages were discovered in a chest, and analysis showed that natron had been used to dehydrate these viscera. Natron is a mixture of sodium carbonate and sodium bicarbonate with impurities, including salt and sodium sulphate, found in natural deposits in Egypt.

This type of mummification continued until the Christian era. Originally reserved for the royal family and upper classes, by the Graeco-Roman period it was practiced by a much wider social group, but the majority of the population, never able to afford this process, continued to be buried in simple graves on the desert edge. No extant account of mummification techniques has ever been found in Egyptian literary or representational sources, although there are scattered references to the procedure and its associated rituals. Classical sources supply the earliest available descriptions, notably in the writings of the Greek historians Herodotus (fifth century BC) and Diodorus Siculus (first century BC). They are not entirely accurate accounts, written centuries after mummification had passed its peak and probably relying to some extent on hearsay, but they do provide a reasonable description of the procedure.

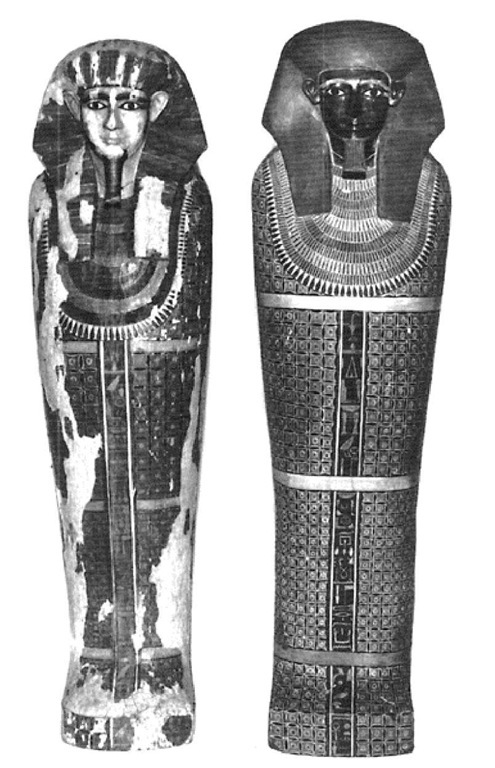

Figure 80 Anthropoid coffins of the two brothers, Khnum-Nakht (left) and Nekht-Ankh. These finely painted wood coffins are good examples of the geometric style of decoration popular in the Middle Kingdom.

Diodorus presents a less detailed account than Herodotus, on whose work his own version may be based, but he provides additional information not found in Herodotus. According to Herodotus, three main methods were available according to cost. In the cheapest method, an unspecified liquid was injected into the body per anum and it was subsequently treated with natron. In the second method, "cedar oil" (perhaps impure turpentine) was injected into the body per anum and then natron was used. The most expensive method, according to recent experiments, has been shown to be the most successful. In this, the brain was removed, partly through mechanical methods and partly through the use of various unspecified substances. An incision was made in the abdominal flank, through which the thoracic and abdominal viscera and contents were removed. The viscera were then cleansed with palm wine and spices, and the body cavities filled with myrrh, cassia and other aromatic substances, before the incision was sewn up. Natron was then used to dehydrate the body, which was finally washed and wrapped in layers of bandages fastened together with gum.

From such literary evidence and from information derived from the mummies themselves, it is evident that there were actually two main stages in mummification. First, the body was eviscerated (although not all mummies underwent this process); only the heart was left in situ, because religion dictated that it was the seat of the intellect and of the emotions, and indeed was the essential part of the person. According to Diodorus, the kidneys were also left in place, but there is little physical evidence to support this claim and no known religious explanation. Subsequently, the eviscerated organs were either stored in special containers called canopic jars, or packaged, in which case they were replaced in the body cavities or placed on the legs of the mummy.

The second stage was to desiccate the body and the viscera by dehydrating the tissues with natron. In addition, the body was anointed with oils and unguents, and in some instances it was coated with resin. Perfumed oils and spices may have been regarded as having some insect repellant properties, or they may have partially concealed the unpleasant odors associated with mummification.

In the long history of mummification, only two major innovations were introduced. From perhaps as early as the Middle Kingdom, the brain was removed, and this procedure became widespread from the New Kingdom. The most usual method was to insert a metal hook via a passage chiseled through the left nostril and the ethmoid bone into the cranial cavity or, less commonly, to intervene through the base of the skull or through a trepanned area. Subsequently, the cranial cavity was probably washed out with a fluid, but some brain tissue was often left behind. The other innovation was an attempt to restore the shrunken body, which resulted from mummification, to a plumper, more lifelike appearance. The face, neck and other areas were packed with various materials (linen, sawdust, earth, sand, and butter), which were either inserted through the mouth or through incisions made in the skin surface. This procedure reached its peak in the 21st Dynasty, when mummification techniques in general were at their zenith.

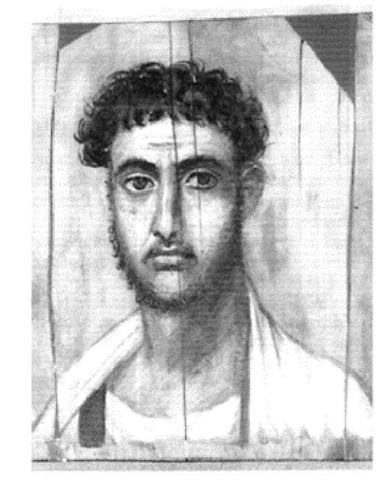

Figure 81 Panel portrait of a man, originally placed over the mummy’s face, showing the clothing and hairstyle fashionable during the Graeco-Roman period.

Musical instruments

Musical instruments from ancient Egyptian tombs have survived in four main categories: idiophones (rattles, clappers), membranophones (drums, tambourines), aerophones (pipes, flute, trumpet, bugle), and chordophones (stringed instruments). In major museum collections, such as those in Cairo, Berlin, London, Paris, Turin, Boston, New York and Philadelphia, idiophones are well represented. Other types are more rare. To supplement the corpus of actual instruments, scenes on temple and tomb walls illustrate music in practice and show how at different periods different ensemble groupings were favored. The absence of any notation implies that musical skills were imparted by word of mouth. This lack is a fundamental impediment to knowledge of how the instruments were played, and theories about rhythms or scales in use can only be conjectural.

The instrument that above all symbolized Egypt for the ancient world was the sistrum. It is the commonest surviving idiophone, and it pervaded the Roman world as an attribute of the goddess Isis. It had two main forms in Egypt, both featuring the goddess Hathor. Essentially a rattle, with sounding plates suspended on metal rods, the sistrum was either arched or in the shape of a miniature rectangular shrine (naos). On temple walls the two types might be featured together, as when they appear in the hands of the emperors Augustus and Nero at the temple of Dendera.

Clappers survive from the Early Dynastic period, and sometimes the ends are carved to represent animal or human heads. Later examples are in the form of a human hand, with a head of Hathor carved below the wrist. Bells and cymbals are comparatively late. Bells were often shaped with the features of the household god Bes. The three main sizes of cymbal mostly date to the Graeco-Roman or Coptic periods.

A cylindrical drum from a tomb at Beni Hasan dating to the 12 th Dynasty and now in the Cairo Museum is the earliest known Egyptian membranophone. A more common type is the barrel-shaped drum, hung by a cord from the neck of the player. Such drums appear mainly in military scenes, but might also have been used at the dedication of a temple. Tambourines also belong to this group. A rectangular tambourine with concave sides was briefly popular in the 18th Dynasty for use at banquets. The more usual shape was a round tambourine of various sizes. This too was featured in banquet scenes in tombs, but it is also shown in the hands of Bes. Elaborately painted skin coverings for such a tambourine are in the collections of the Cairo Museum, and the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

The end-blown flute is the characteristic aerophone of the Old Kingdom, though the earliest surviving example, again from Beni Hasan, dates from the Middle Kingdom. Such flutes were used throughout Egyptian history and have survived into modern times as the nay. Parallel pipes played with a single reed, of the clarinet type, were also common in the Old Kingdom, whereas pipes with a double reed were introduced in the New Kingdom. Very slender and easily damaged, these two-pipe instruments were held to make an acute angle between them.

Trumpets and bugles are shown in military scenes, and two such instruments are among the artifacts from Tutankhamen’s tomb. One is of silver, and the other is of bronze or copper. Both are decorated with scenes involving Egypt’s chief regimental gods. A monkey-shaped ocarina (ceramic pipe) and Graeco-Roman rhytons (drinking horns) used as musical instruments are among the rarer aerophones in the Cairo Museum.

The main Egyptian stringed instrument or chordophone was the harp. It assumed various shapes and sizes during its long history. The type with neck and soundbox making a continuous curve was the characteristic Egyptian harp. It might be as large as the magisterial instruments which tower above the standing players in scenes from the tomb of Ramesses III, or as small as those held on the shoulder in scenes of New Kingdom feasts. The angular harp, usually with horizontal neck at a right angle to the vertical soundbox, may be an import from Asia.

Neither the lyre nor the lute appear to be indigenous instruments. The lyre makes an early appearance in the tomb of Khnumhotep (No. 3) at Beni Hasan in the hands of an Asiatic bedouin from the Eastern Desert, but both instruments achieve popularity in the chamber groups of the New Kingdom. The lyre was either symmetrical like the modern tambour, or asymmetrical and trapezoidal in profile. The lute could have either a long wooden soundbox or a smaller one of tortoise shell. It was played with a plectrum.

A typical ensemble depicted in Old Kingdom tomb scenes consists of an end-blown flute, double parallel pipes and a harp. The player, always male, may be seated opposite a musician who seems to be directing the performance with various hand gestures. In the Middle Kingdom female musicians assume a larger part in tomb scenes, and the parallel pipes tend to disappear. The importance of music in the Middle Kingdom is seen in the presence of harpists and singers among the wooden models made for a nobleman’s tomb, his "house of eternity."

Theban tombs of the New Kingdom and later have many musical scenes. Tuthmose III’s vizier Rekhmire had three such scenes represented in his tomb. Female players, often scantily clad and probably professional musicians, tend to predominate. The ensemble may contain all three stringed instruments, a pair of angled pipes, and a tambourine, while a female dancer weaves back and forth among the musicians. Final testimony to the popularity of music among the Egyptians is the caricature of such an ensemble, with a lion, crocodile, ass or monkey shown playing the different instruments.

Mythology

Mythology can be found everywhere and nowhere in ancient Egypt, depending on how rigorously our modern definition of the term is applied. Clearly, the many religious texts that survive include mythological allusions, as do literary, non-literary and historical texts. The same can be said of many artifacts. A single mythology or even a compendium of myths or mythologies has not survived, however, and probably never would have been composed in antiquity. The basics of the myths were learned by children, probably with different emphases in different times and places, and much would have been added to the basics as the children grew older and encountered both variations and modifications that had been proposed by priests or advocated by the king. From what has survived, it is obvious that both the king and some priests of the principal temples of Egypt would have been involved in mythologizing. The myth of "divine kingship" itself became the focal point of Egyptian mythology, and the reason why most other myths were recorded at all was in order to associate them with this myth.

The earliest recorded mythological allusions with any depth of detail are found in the Pyramid Texts carved on the walls of the burial chamber in the Saqqara pyramid of King Unas, the last king of the 5th Dynasty. In general, these texts were collected and composed to provide a guide for the king in the afterlife on his way to join the other great gods. The principal tradition upon which the mystery of the king’s death is imposed is the great sun cult of Heliopolis, located across the river from Giza on the east bank. Re, who traverses the sky during the day and the area beyond the visible sky at night, is a "father" of the king, who is joined by the king, who is accompanied and guarded by him, and who is glorified by every pyramid, obelisk and sun temple erected by the king on earth. That the king is the "son of Re" is constantly reiterated in his royal titulary as well as being expounded in his Pyramid Texts. The complete titulary, that would have been seen by many, included other associations with divinity that are also encountered and elaborated upon in the funerary literature.

First and foremost, the king himself is identified with the god Horus. It is clear that there were several earlier falcon gods whose significance and expansiveness may have varied in their original cult centers, but whose cumulative attributes were sufficient for the divine equation to succeed on a grand scale. The genealogy of this Horus is one of the finest and clearest examples of Egyptian mythology, preserved in allusions from all periods, outlined already in the Pyramid Texts, recorded in a Late Egyptian story (New Kingdom), and preserved in classical literature, principally in Plutarch’s De Iside et Osiride (Concerning Isis and Osiris).

This cosmological, cosmogonical myth places Horus in the fourth generation from the creator god, Atum (meaning the "complete one"), a sky god who himself produced the first pair of chthonic deities, Shu ("air") and Tefnut ("moisture"). Atum’s creative force is variously described as his spitting, vomiting or masturbating, but his first generation of a male and female pair leads to their procreation of the second generation, Geb ("earth") and Nut (the "watery sky"). The next generation, anthropomorphic rather than chthonic, consists of two brothers and their two sister-spouses, Osiris and Seth, Isis and Nephthys. The older son Osiris became the god-king of his father’s domain, the earth, but his jealous brother Seth connived to assume his throne. Osiris was killed and dismembered. Through his death he became god of the dead and through his dismemberment he became the source (etiology) of numerous shrines and cult temples throughout Egypt, where the parts of his body were buried. His beloved sister-wife, Isis, reassembled the body parts so that Osiris could father her son, Horus, who would avenge the death of his father and become the living god and god of all the living.

The enmity between Osiris and Seth can be seen as the struggle between the older but weaker son and his younger and stronger brother, between the Black Land (Kemet, i.e. Egypt) and the Red Land (Deshret). Through his death and resurrection, Osiris symbolized7 the Nile and its fertile black valley (the Black Land), the flood and subsequent harvest, while Seth represented the encroaching, untamed desert (the Red Land), as well as the destructive storm. The conflict of Horus and Seth is likewise symbolic of the triumph of good over evil, the loss (sacrifice, offering) of Horus’s eye in the struggle to avenge the wrong done to his father by his uncle, the victory of intellect over brute force, and the resolution of the problem of succession, with that from father to son winning out over that from brother to brother.

The ennead (nine gods) representing the family tree of Horus was a Heliopolitan invention. which at some time prior to the earliest Pyramid Texts was identified with Hathor (the House of Horus). This great goddess, who undoubtedly had her own extensive following and clergy, to judge from the surviving titles of her priestesses, thus became another mother of the king along with Isis and Nut (who was really his grandmother). Already in the Old Kingdom the mythology that was central to the divine kingship had been interlaced with old and new ideas, part of a conscious effort to include all the major deities and cults by linking them to the most powerful visible representative they had on earth (the Horus-king).

The Heliopolitan priests who adopted the very old Osiris-Horus myth to their own old (Atum) and new (Re) mythological constructions did not stop there, but also incorporated mythological material from many other cults, especially the creation story from the cult center at Hermopolis in Middle Egypt. This was not difficult since the great god of Hermopolis, Thoth, the god of the moon, wisdom and writing, could be subsumed under the Heliopolitan creator god (Atum), and Thoth’s antecedents could be made the real primordial source for Atum himself. At Hermopolis, four male and female pairs of divine beings representing aspects of the cosmos before creation comprised an ogdoad (eight gods), which produced an egg that developed on an island that appeared in the middle of the Nile as the flood receded; from this egg, the creator god was born. The pairs included Amen and Amaunet (representing "hiddenness"), Huh and Hauhet ("formlessness"), Kuk and Kauket ("darkness"), and Nun and Naunet ("watery abyss"). These deities were represented anthropomorphically at a much later date, but in their original conception seem to have been chthonic at least and perhaps better considered as elements of pre-creation chaos. Unfortunately, the original Hermopolitan myth does not survive. However, the Heliopolitan adaptation in the Pyramid Texts would seem to indicate the myth’s great antiquity, the fact that it was credited with chronological priority, and the significance of Hermopolis as an early cult center, renowned as the birthplace of the gods and later as a source for important old religious texts: a tradition as old as the Old Kingdom and surviving to the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

The gods of Memphis, Ptah, Sekhmet, Nefertem, Tatennen and Sokar should be the deities most clearly associated with the king of Egypt, since Memphis by tradition was established as the capital by Menes, the first king of the 1st Dynasty, and this king is also supposed to have erected the first great temple there. The Memphite gods are mentioned early enough in texts, but neither as a familial triad plus mortuary god, as they appear later, nor in the context of the creation story credited to Ptah in a much later text. An inscription from the reign of the Kushite king Shabako (25th Dynasty) identifies Ptah with both of the last two deities of the Hermopolitan cosmogony, Nun and Naunet, so that this creator is placed between the ogdoad and the ennead, but while he is somewhat and rogynous, he creates by conceiving in his heart and speaking with his tongue. Thus he creates Atum and everything else ex nihilo, paralleling one of the creation stories in the Book of Genesis and prefiguring the Logos doctrine of St John’s Gospel as well. Ptah’s consort, Sekhmet, must have had many of the good characteristics of the other goddesses with whom she is later identified, but she is known as a "powerful one" from her name and hundreds of lioness-headed statues from the New Kingdom. From at least one mythological story she is known as a slayer of men identified with Hathor. Nefertem, the son of Ptah and Sekhmet, is also encountered separately as the young sun god arising from a lotus. The connection with the sun cult is significant, but the mythological text that links this triad to the Memphite creation story is still lacking. Sokar, the Memphite mortuary god, is found in early texts, but is apparently no competitor for Osiris’s position until guidebooks to the afterlife are found in New Kingdom royal tombs with Sokar predominant as the god of the domain through which the sun bark passes at night. Somewhat later abbreviated versions of the funerary text called the Book of Amduat ("that which is in the Netherworld") are found in papyri belonging to individuals who also had copies of the Book of the Dead.

Because Thebes was the power base of the dynasties that founded both the Middle and the New Kingdoms, the Theban gods had to be associated politically as well as mythologically with the other great gods of Egypt. The triad of Amen, Mut and Khonsu was a very fitting group to do all that was necessary to link Thebes both to its allies and to the old religions. The name "Amen" was that of the first of the primordial gods of Hermopolis, but at Thebes the god took on the characteristics of the Theban war god, Montu, as well as the attributes of the ithyphallic fertility god Min from neighboring Coptos (Quft/Qift). The site of Thebes became sacred through the claim that the ogdoad was buried there. Mut "the mother" is easily equated to Isis, Hathor and Sekhmet, and her son Khonsu, a moon god, helps to solidify the link between the two elements of Amen-Re, and at the same time to connect Amen with Thoth, thus enhancing the Theban family’s devotion to the moon god. A late mythological text from Thebes has Amen-Re come from Thebes to Hermopolis as Ptah "to open" (PW, in Egyptian) Hathor, create the ogdoad, and as Khonsu to travel back to Thebes. All of the mythological associations and word play in this Ptolemaic text would not necessarily have been early New Kingdom thinking, but the notion of the Theban site of Medinet Habu (ancient Djeme) as the burial place of the ogdoad apparently was noted already in the reign of Queen Hatshepsut (18th Dynasty).

Clearly, many of the Egyptian myths were elaborated upon and embellished over time, but the sketchy bits that survive in early texts dealing with many other deities could also be merely hints at fuller versions with which the people were familiar. There are, of course, many other partial allusions to powerful local deities, creation stories and etiologies that could be presented here, but since the myths have to be pieced together from disparate sources, they remain for the most part hypothetical.