Mortuary beliefs

In Egypt, mortuary beliefs and customs were undoubtedly influenced initially by the nature of the land and its climate. With inadequate rainfall to support crops and domesticated animals, Egyptians awaited the annual inundation of the Nile to irrigate and cultivate their fields. This cultivated strip on either side of the river was called Kemet (the "Black Land"), referring to the rich black silt which the river deposited there and which enabled them to grow excellent crops. Here they lived and farmed, but the bodies were taken and interred in the desert which lay beyond. Feared as a place of death and terror, this desolate area was known as Deshret (the "Red Land"), referring to the color of the sand and rocks. Here, the heat of the sun and the dryness of the sand provided ideal environmental conditions which preserved the bodies (natural mummification) and the artifacts placed in the graves. Later, artificial methods were introduced to achieve long-term preservation of the bodies, making use of chemical dehydrating agents.

The contrast between the cultivation and the desert symbolized the difference between life and death for the Egyptians and probably inspired some of their earliest and most enduring religious concepts. The evidence of grave goods probably indicates that funerary preparations to facilitate the deceased’s journey after death were undertaken from earliest times, and that there was an awareness of an individual’s continued existence after death. The idea of eternity remained a constant feature of the religion, although the exact state and place of this continued existence were envisaged in several ways.

It was believed that each individual experienced a cycle of life, death, and rebirth, reflecting the annual destruction of the vegetation, due to the parching of the land, and the subsequent resurgence of life which the Nile’s inundation brought about. One of Egypt’s greatest gods, Osiris, was both vegetation god and king of the underworld; mythology described his annual death as a human king and resurrection as ruler of the underworld. This reflected the natural phenomena and enabled him to offer the chance of resurrection and eternal life to his worshippers. Similarly, Egypt’s other great life force, the sun, underwent a daily death but was renewed at dawn, and consequently Re the sun god was regarded as both a great creative force and the sustainer of life. The essential feature of Egyptian mortuary beliefs and customs was the denial of death and the continued affirmation of eternal existence.

The human personality was regarded as a complex entity. The body formed the essential link between the deceased’s spirit and his former earthly existence; every attempt was made to preserve it (using mummification techniques for those who could afford them) and to protect it with a tomb and magical spells. It was believed that the spirit returned to the body to partake of the food offerings placed at the tomb, to gain continuing sustenance. Statues of the tomb owner and magical formulas inscribed in the tomb were intended to provide a secondary method of nourishing the spirit, if the mummy should be destroyed.

A person’s name was regarded as an integral part of his personality, and knowledge of this could enable others to direct good or evil forces toward him. Also, his body and statue were identified by name inscriptions, as part of the funerary procedure. His shadow, another element of his personality, was believed to incorporate his procreative powers.

Some aspects of this complex personality, however, were only released after death. The most important was the ka (often translated as "spirit") which, in its owner’s lifetime, was regarded as the embodiment of the life force and the essential "self" or personality, as well as his double. It acted as guide and protector, and after death it was thought to be released as a separate entity which progressed to achieve immortality but retained a continuing and important association with the place of burial, being dependent on the food and other goods placed there for its sustenance. The ka is usually shown as a human with upraised arms, or simply as a pair of upraised arms. Another aspect of the human personality, also believed to survive death, was the ba (sometimes translated as the "soul"). This force, shown as a human-headed bird, could leave the body and tomb and travel to places which the owner had enjoyed during his lifetime. Another supernatural force known as the akh (again depicted as a bird) could be called upon to assist the deceased.

Although royalty, wealthy persons and the poor had different expectations regarding the nature and location of their individual existences after death, all placed great emphasis on the correct procedure of the funerary rituals and on the provision of a properly prepared and equipped burial place. A vital ritual in the burial service was the ceremony of "Opening the Mouth," performed by the deceased’s heir. He touched with an adze the deceased’s mummy, statues and other representations in the tomb, to restore the life force to them and to enable the spirit to use the body throughout eternity.

Great consideration was also given to provisioning the tomb with food and drink. This was primarily the duty of a person’s heir and descendants, but succeeding generations often neglected this task, threatening the owner’s ka with starvation, and so other methods were adopted. A ka priest could be employed to place the daily provisions at the tomb and to recite the necessary prayers; he and his descendants (to whom the obligation passed) would be paid with provisions from land specially set aside in the dead man’s estate. However, even such an endowment could not guarantee that the tomb would be attended in perpetuity, and other measures were introduced. The interior walls of tombs were carved and painted with registers of scenes showing food production and other activities; these could be magically activated for the deceased to enjoy throughout eternity. Also, an offering formula was inscribed on one wall giving details of the food that would be continually available, and model figures of brewers, bakers, butchers and other workers were included to ensure an eternal abundance.

Access to his possessions and to the pleasurable experiences once enjoyed in life was thus obtained for the wealthy commoner. He hoped the afterlife would be a continuation of this existence, but free from danger, illness or worry. He expected to pass time in his tomb, surrounded by the scenes and possessions which reflected the best aspects of his life, and he expended considerable wealth in order to ensure a comfortable eternity.

The king, however, had different expectations. He would ascend to the heavens where he hoped to join his father, the sun god Re, and to sail with him and other deities in the two celestial barks. The earth was envisaged as a flat surface, suspended within a circle. Above the earth’s surface, the semicircle formed the sky where the sun sailed throughout the daytime, while at night, it continued its course in another bark, passing through the semicircle beneath the earth (the underworld). Every day, the sun re-emerged at dawn on the earth’s surface. Throughout ancient Egypt’s history, the major architectural, decorative and inscriptional features of the king’s burial place were intended to achieve two main aims: to ensure that the king safely completed his journey after death, overcoming all dangers on his way; and to establish that he would be received as a divine ruler by the gods and allowed to retain this status throughout eternity. During the Old Kingdom, the kings introduced the custom of building pyramids. Each pyramid contained the royal burial and funerary possessions, while other elements of the complex included a mortuary temple, causeway and valley temple, where the burial ceremony and mortuary cult took place. The pyramids were probably closely associated with the sun cult and may have been regarded as "ramps" linking earth and sky, thus enabling the king’s spirit to ascend to heaven and return again at will to partake of his earthly food offerings. Later, in the 5th Dynasty, when royal political power had declined and the construction of the pyramids was less substantial, reliance was placed instead on magic spells. Now, the Pyramid Texts were inscribed on walls inside the pyramids, to ensure the king’s resurrection by means of magic. In the New Kingdom, when pyramids were abandoned in favor of rock-cut tombs in the Valley of the Kings at Thebes, wall scenes inside the royal tombs depicted the king’s journey through the underworld, based on the magical Books of the Netherworld. Again, these were intended to ensure the defeat of death.

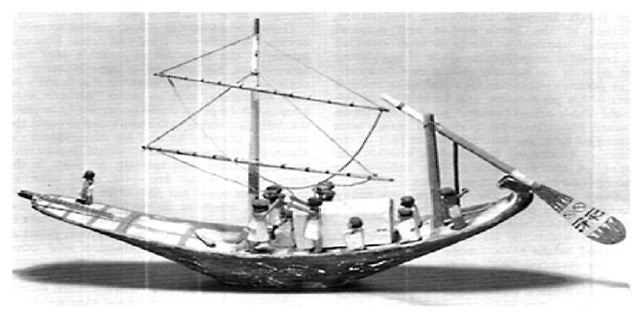

Figure 77 Wooden model boat with crew, intended for the tomb owner to sail south (upstream) with the wind.

There was also a wooden model rowing boat in this tomb, for traveling north (downstream). From the Tomb of Two Brothers, Rifa, 12th Dynasty, circa. 1900 BC.

However, not only royalty and the wealthy were able to claim a chance of eternal life. In the Old Kingdom, only the king could expect an individual immortality and others only hoped to experience this vicariously, as a reward for serving the god-king during life. However, with the political collapse of the Old Kingdom at the end of the 6th Dynasty, the power of the king and his patron deity Re waned considerably, and Osiris emerged with greater popularity. A vegetation god and ruler of the underworld, Osiris received widespread worship and acclaim as a giver of life and fertility, gaining the attributes of a divine judge and symbolizing the victory of good over evil. His annual triumph over death, expressed in the renewal of the vegetation, resulted in his installation as ruler of the dead and of the underworld. The successful outcome of his own trial before the divine judges and his personal resurrection enabled him to promise eternal life to each of his followers. This was not dependent on the king’s favor or the performance of the correct rituals and burial procedures, but could now be achieved through devoted worship of Osiris and the pursuance of an exemplary life. At the Day of Judgement, an individual faced the divine tribunal and was required to give an honest account of his deeds. Those worthy enough to achieve immortality now passed to the land of Osiris (situated somewhere in the west), where they were required to till a small piece of land in perpetuity, amidst surroundings that reflected the world of the living. Although this held out the promise of happiness for the poor, wealthier persons did not wish to spend their eternity in agricultural pursuits and took care to provision their tombs with sets of model agricultural workers (shawabtis) and overseers, to undertake these labors on their behalf.

The Pyramid Texts, the preserve of royalty in the Old Kingdom, were now, as the Coffin Texts, changed and used on the coffins of commoners to ensure their resurrection and eternity. There was also a great increase in the number of well-equipped tombs, many of which were now prepared for the middle classes. They were supplied with a variety of model servants, soldiers and animals for use in the next world, some of them based on the subject matter of wall scenes found in Old Kingdom tombs. After the successful outcome of his trial, each deceased person could now place the words "justified" or "true of voice" after his name in the funerary inscriptions, and the name "Osiris" in front of his own name.

The three main concepts of eternity therefore began to be formulated in the Middle Kingdom: the royal celestial hereafter, continuation of existence within the tomb for the wealthy owner, and, for the poor, an eternity spent tilling the land in the Kingdom of Osiris. To some extent, these concepts were interchangeable and the priests later attempted to rationalize them to some degree. Essentially, however, they remained distinct until the end of the pharaonic period, reflecting the separate aspirations of the country’s main social groups.

Mummies, scientific study of

Investigations of Egyptian mummies in many ways reflect the state of the sciences and particularly the focus of the medical sciences at any given time. It is, therefore, no accident that many of the primary investigators are physic ians, physical anthropologists, anatomists, bacteriologists, biochemists and others closely related to the health sciences.

The great progress in diagnostic procedures, including biochemistry, microscopy, molecular genetics, and radiographic techniques in the medical profession, is mirrored in the diversity of specialists investigating mummies today. Hence, mummy-related investigations are published in every conceivable science journal. Unfortunately, relatively few articles on human remains have appeared in Egyptology journals such as the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. The major sources of scientific interest in Egyptian mummies are reviewed here.

The terms "mummy" and "mummification" have traditionally been applied by most laymen and scholars to human and animal remains that have been preserved by priest specialists in ancient Egypt. The term "mummy" comes from the Persian word mumia, meaning "bitumen" or "tar." The coating over the body, which frequently turns black in color with age, was originally a molten resin derived from trees and used during the mummification process. Today, the terms "mummy," "mummification" and "mummified" all refer to any animal or human remains that have been preserved by natural means or through human intervention.

The key to preservation is usually the removal of water from the tissues. In Predynastic times this was accomplished naturally when the remains were placed directly in the sandy floor of a grave pit excavated in the desert, where rapid dehydration or desiccation occurred. Anywhere in the world today where the climate is arid, mummified remains will be found, for example in the African Deserts, the US south-western deserts, Mexico and Peru.

From the Old Kingdom through the Roman period there was great diversity in the process by which the body was preserved. Two Greek historians, Herodotus (fifth century BC) and Diodorus (first century BC), gave the best known accounts of mummification in antiquity. In recent times, Zaki Iskander, both an Egyptologist and a biochemist with the Egyptian Antiquities Organization, has not only studied the chemistry of mummification but also has successfully mummified animals. Alfred Lucas, a biochemist, has also analyzed and published the chemistry of techniques used in ancient mummification.

The process was basically dehydration or desiccation utilizing dry natron (sodium carbonate and sodium bicarbonate) for some forty days. Natron was found in ancient lake beds such as the Wadi el-Natrun. Usually, the viscera were removed and preserved separately and only the heart and kidneys remained in the body cavities. The brain was frequently removed through the nasal septum utilizing picks and dissolving chemicals. The body and viscera were washed with palm oils and spices and then sealed with molten resin from the sap of trees. The body was wrapped in many layers of linen and placed inside of one or more coffins. Most coffins were made of wood. In royal burials coffins were sometimes covered with gold leaf or pure gold and were then placed inside of a stone sarcophagus.

Over the 5,000-year history of Egyptian mummification, great variation has been observed. The brain and viscera were not always removed. Sometimes the viscera were placed back into the body. Many different kinds of natron and resins were used to preserve the body. By the late Roman period, the most beautiful mummy cases and wrappings often contain a badly preserved mummy that was essentially only a skeleton.

What preserved the body was principally dehydration. The resin, the linen wrappings and the coffin all helped to protect the body from outside environmental contaminants, especially bacteria and oxygen. However, it is the dehydration of tissues that has caused the major problem to the histologic and pathologic study of the tissues derived from the ancient mummies.

Scientific investigation of mummies may be divided into two major categories: first, the non-destructive study of wrapped or unwrapped mummies, and, secondly, the dissection or autopsy of mummies. The first category includes visual examination, cranial, post-cranial and soft tissue measurements, photographs, full body radiographic surveys, cephalometrics, CAT Scans or CTs (Computed Axial Tomagraphy) and MRIs (Magnetic Resonance Imaging).

Artists and scientists accompanying Napoleon’s expeditionary forces in Egypt at the end of the eighteenth century were the first to observe, describe and record mummies and their tombs. Some tomb paintings indicated disease, nutrition, deformity, trauma and even medical treatment. Since the publication in 1875 of the Ebers papyrus, many other medically related papyri have been published, including the Kahun (1898), the Hearst (1905), the Edwin Smith (1930) and the Chester Beatty papyrus (1935). These papyri have been examined extensively yielding insights not only into the diseases of ancient Egypt, but also the practice of medicine.

In 1834 Thomas Pedigrew wrote the History of Egyptian Mummies, the first major publication encompassing historical sources as well as current investigations into mummification at that time. Royal mummies found at Deir el-Bahri by Emile Brugsch in 1881 were later unwrapped by Gaston Maspero before distinguished guests and royalty in the Cairo Museum. In 1895, Maspero published his physical anthropological measurements of height and physical appearance. Also important for these studies, another cache of royal mummies was discovered by Victor Loret in 1898 in the tomb of Amenhotep II.

The building of the first Aswan Dam in 1902 and its enlargement in 1907 resulted in a large-scale archaeological study of the areas to be inundated, especially between the First and Second Cataracts. Archaeological evidence from these areas, including the human remains, was described by George Reisner (1910) and by Warren Dawson (1938). In 1924 Dawson and Elliot Smith published another major work on mummies and mummification, Egyptian Mummies.

In his definitive 1912 book, The Royal Mummies, Smith gave a detailed, written description (often quoting Maspero) with photographs of the New Kingdom royal mummies in the Cairo Museum. It was Smith who recommended X-ray studies of the royal mummies, and in 1903, at Douglas Derry’s request, the mummy of Tuthmose IV was X-rayed by a Dr. Khayet. Beginning in 1968, all of the New Kingdom royal mummies in the Cairo Museum have been examined by James Harris and colleagues utilizing Ytterbium 169, conventional X-rays and cephalometrics. The latter permitted quantification and the biostatistical comparison of the craniofacial skeletons within families and between various populations.

In 1927 Derry published his examination of the mummy of Tutankhamen, whose tomb was discovered by Howard Carter in 1922. A dentist, Filce Leek, with the anatomist R.G.Harrison, X-rayed the skull (utilizing radioactive iodine) and the mummy of Tutankhamen in 1968. Harris secured cephalometric X-rays of Tutankhamen in his tomb in 1978. The later study suggested the similarity of the skull of Tutankhamen to that of Smenkhkare, and suggested that the young pharaoh had died in his early twenties.

Many museums throughout the Americas and Europe have X-rayed their mummy collections over the years. In 1967 Peter Gray utilized radiographs to examine some 133 mummies in Great Britain, France and Holland. Recently, CTs and MRIs have proven to be increasingly popular approaches to non-invasive examination of mummy collections. The Manchester Museum, the University Museum in Philadelphia and the Field Museum in Chicago are examples of museums which have used radiographic techniques to record and examine their mummy collections.

Radiographic studies may yield considerable information about health and disease in the skeleton and soft tissue. Studies of the royal mummies in the Cairo Museum have revealed, for example, antemortem and postmortem trauma, cranial defects, poliomyelitis, arteriosclerosis, rheumatoid and hypertrophic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, malocclusion, impacted teeth, dental abscess and so on. In 1971 Walter Whitehouse, a professor of radiology, observed that the most common abnormality in the royal mummies was hypertrophic or degenerative arthritis. The mummy of Amenhotep II showed striking evidence of ankylosing spondylitis (arthritis of the spine). Although Elliot Smith had observed Talipes equinovarus (clubfoot) in the lower extremity of the mummy of Siptah, radiological examination indicated that the deformity strongly resembled a postpoliomyelitis deformity. Arteriosclerosis (extensive vascular calcification) was observed in the mummies of Ramesses II, Seti I, Merenptah and Ramesses III.

Radiographic examination is helpful in confirming the sex and skeletal and dental age of the individual. The open epiphyseal plates in the knee X-rays of Tuthmose I would suggest that the mummy was not yet eighteen years of age.

Cephalometric radiographs, which are taken with a precise orientation to the mid-sagittal plane of the skull, permit the measurements and biostatistical comparisons of one mummy to another, a family or any given population. This approach is particularly helpful in determining the genetic or family background of the individual under study. The University of Michigan teams have recorded over 5,000 cephalograms of Old Kingdom nobles from Aswan and the Giza plateau, New Kingdom royal mummies, New Kingdom elites from Deir el-Bahri, and Nubians (AD 200 to the present). Multivariate statistical analyses of the computerized tracings and measurements of these cephalograms have revealed the relative homogeneity of the Egyptians, while indicating the great diversity or heterogeneity of the New Kingdom royal mummies. The craniofacial skeleton and dentition of the New Kingdom pharaohs and queens reflect the malocclusions (dental crowding and maxillary prognathism) observed in Western societies today.

Radiographs are also very helpful in discovering and interpreting the funerary artifacts placed inside of the wrappings. Heart scarabs, amulets of the sons of Horus, beads, bracelets, necklaces, rings, arm bands and so on all help to confirm the period in which the individual lived and died. Radiographs have limitations, but they permit nondestructive studies so that the wrapped or unwrapped mummy remains intact for future generations.

The second approach to the study of mummies is to biopsy, dissect or autopsy the mummy, similar in techniques to modern surgery and pathology. Most mummies which have been autopsied are poorly preserved ones in museums or private collections. Many investigators in this area are members of the Paleopathology Association, which holds annual, national and international meetings and publishes the Paleo-pathology Newsletter. The membership consists principally of physicians and physical anthro pologists with a special interest in pathology or paleopathology. The Manchester Museum is an example of where both paleopathology and the public exhibition of mummy unwrapping and dissection have been conducted by Rosalie David and associates.

Figure 78 X-ray of King Siptah, demonstrating poliomyelitis (left leg)

The major problem in utilizing modern pathologic procedures to examine disease in ancient Egyptian mummies has been the rehydration of the tissue since the water was so laboriously removed by the priests of ancient Egypt. Armand Ruffer, a bacteriologist at the School of Medicine in Cairo at the beginning of the First World War, is considered the pioneer in restoring mummified tissue and his techniques, although modified, are frequently utilized today. More recently Sandison has recommended a hydration solution of 95 percent ethyl alcohol, 1 percent aqueous formalin and 5 percent aqueous sodium carbonate.

Once tissue has been rehydrated, is can be treated with care in the conventional setting of a pathology laboratory. Many data published on disease in ancient Egyptian mummies come from this source. Histologists or histopathologists in studies of autopsied mummies in various museums have found evidence of pneumoconiosis, smallpox, pericarditis, intestinal parasites, schistosomiasis and other medical conditions.

Paleobiochemistry has been reviewed by Robin Barraco. The study of proteins, salts and lipids may yield considerable insight into diet, disease, age and sex and general lifestyles. Trace elements, such as lead, zinc, copper, arsenic and mercury, may be utilized to determine the effects of the environment, pollution, nutrition, illness and social differentiation on ancient populations. Methods of measuring elements in mummified tissue include electrochemical, optical spectrometry, X-ray spectrometry, radioisotope and mass spectrometry. Scanning and transmission electron microscopy have been utilized to investigate the microstructure of bone, cartilage, muscle, sclera, blood, teeth, hair, and even ancient textiles. Many of these techniques were applied by French scientists and Egyptologists when they removed the mummy of Ramesses II to the Museum of Man in Paris under the direction of Christine Desroches-Noblecourt and Lionel Balout.

Figure 79 X-ray of Queen Nodjme, revealing a sacred heart scarab and amulets of the four sons of Horus within the mummy.

Dental paleopathology, including both the dentition and their supporting structures, has received considerable attention through the years because of the relative indestructibility of teeth through time. Tooth size, shape, number of cusps, root lengths, missing teeth, and supernumerary teeth have been demonstrated to have a strong genetic component. The growth and development of teeth as well as attrition or wear have long been utilized to indicate dental age. Dental caries and periodontal disease, including bone loss and dental calculus (tartar), are often excellent indicators of diet. Enamel or dental hypoplasia may indicate severe onset of disease during the formation of the dentition. Dental caries (tooth decay) were not a major problem in the early Egyptians, compared to the wear or attrition of the dentition which led to pulp exposure and dental abscesses. Ancient Egyptians (as well as modern Egyptians) suffered most severely from dental calculus (heavy tartar) leading to periodontal disease or loss of the supporting bone around the dentition.

Another approach of considerable interest over the past twenty years or so has been serology (the examination of blood groups or blood antigens, usually derived from epithelium or muscle tissue). In an attempt to derive familial relationship between the pharaohs of the late 18th Dynasty, R.G.Harrison compared the mummies of Yuya, Tuya, Amenhotep III, Queen Tiye and Smenkhkare to Tutankhamen’s utilizing ABO and Mn blood groups. However, other investigators have recently warned about the difficulty in controlling against false positive or false negative results. The latter may occur as the result of contaminating bacterial enzymes. F.W. Rosing has noted that ABO tests were successful from brain tissue, but not from epithelium and muscle tissue.

The latest area of interest has been the DNA fingerprinting or gene sequencing in mummified tissue. One investigator, Svante Paabo, has published the success of DNA sequencing in only one out of twenty specimens examined. There has been considerable difficulty with DNA amplification in mummified tissue, and the supposition of random mating basic to DNA fingerprinting may be questionable in ancient Egyptian populations.

It should be mentioned that besides the mummy itself, there has been considerable interest in the funerary artifacts. Linen wrappings, plant resins, natron crystals, jewelry, wigs, paint pigments and so on have all been studied for composition and possible derivation. Spectrometry, chromatography and other chemical tests have frequently resulted in discovering the composition of the artifacts, their geographic origins, and subsequently the dating of the burial.

The scientific study of mummies is as varied, then, as the research backgrounds and disciplines of the investigators. In this age of specialization, many articles are placed in medical and scientific journals published for a narrow audience and frequently are not readily known or available to Egyptologists. Those published studies with important implications for Egyptologists should be repeated with technology proven to be reliable in mummified tissue. Finally, the potential contribution of the research scientist will depend not only upon the advancement of science and technology, but even more importantly on greater interaction with Egyptologists and archaeologists.