Medinet Habu

The "city of Habu" designates primarily the town that arose in and around the temple enclosure of Ramesses III on the west bank of the Nile (25°43′ N, 32°36′ E), opposite the ancient city of Thebes (modern Luxor). This modern name probably reflects the settlement’s proximity to the temple of a local saint, Amenhotep the son of Hapu, who lived in the fourteenth century BC and was especially revered in the Graeco-Roman period. Modern knowledge of the remains at Medinet Habu itself owes much to the Architectural and Epigraphic Surveys of the Oriental Institute (Chicago), which have worked at the site from the mid-1920s down to the present. This entry covers the following structures: (1) the "Small Temple" of the 18th Dynasty; (2) the mortuary temple of Ramesses II; (3) associated and later chapels; and finally (4) the town of Djeme.

Named "Holy of Place," the small 18th Dynasty temple was begun in the joint reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III. Its foundations rest on the remains of an earlier temple, but there is no proof that the cult predates the New Kingdom. The area was known as "the mound of the west" during the 18th Dynasty, but by the eleventh century BC it had been given a more specific name, Iat Tchamuwe, "the mound of the males and mothers," which refers to the eight creator gods and goddesses (ogdoad) who were believed to be buried here. It is from this later cult name that arose the term "Djeme," which was attached to the entire site through late antiquity.

The 18th Dynasty building consisted of two parts, a bark shrine surrounded by pillared porticoes, and the temple proper. The inner chambers of the temple were decorated with reliefs that preserve their paint in almost pristine condition under grime that was removed in the early 1980s by conservators. The interior contains two sets of cult rooms dedicated to different manifestations of Amen; there is also a separate chapel which opens onto the portico at the northeast corner of the building. This chapel (which was devoted to the royal cult), along with the portico and bark shrine, are entirely the work of Tuthmose III, who usurped or erased the figures of his aunt inside the cult rooms of Amen. During the Late period part of the temple’s rear wall was temporarily dismantled so that a naos could be inserted into the inner sanctuary that lies behind the royal cult chapel. What gave the small temple its longevity was its cult. Unlike the mortuary temples in West Thebes, which could depend neither on their size nor even their owners’ posthumous fame for their endurance, this temple was dedicated to a god who embodied the very mysteries of death and resurrection. Amen of Luxor Temple, toward which the small temple was oriented, visited the site every ten days; during this Feast of the Decade he underwent a series of transformations that ended in his own rebirth. The association of the ogdoad with this place heightened its significance, for it became the "underworld" in which the primeval forms of Amen and the eight creator gods rested and yet "lived" mystically within the cycle of nature. Thus this building, which housed processes of such relevance in the city of the dead, not only lasted but grew.

The first structural addition to the small temple was made during the 25th Dynasty, when the Kushite kings built a pylon connected to the older temple by a gallery which one of the later Ptolemies replaced with a wider columned hall. The small wings attached to either side of Tuthmose III’s fagade are probably also Ptolemaic in date. Even before this, the sagging roof of Tuthmose III’s pillared portico had to be shored up by Hakor (29th Dynasty). At about the same time, a columned portico was added in front of the "Ethiopian" pylon by a king whose names were usurped by Nectanebo I (30th Dynasty). This served as the temple’s front entrance until about 100 BC, when a massive pylon fagade was built in front of the precinct’s mudbrick enclosure wall. The final, equally impressive addition to the complex was begun under the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius. The plan was to hide the Ptolemaic pylon behind a huge columned porch fronted by a large courtyard, but this project was never completed.

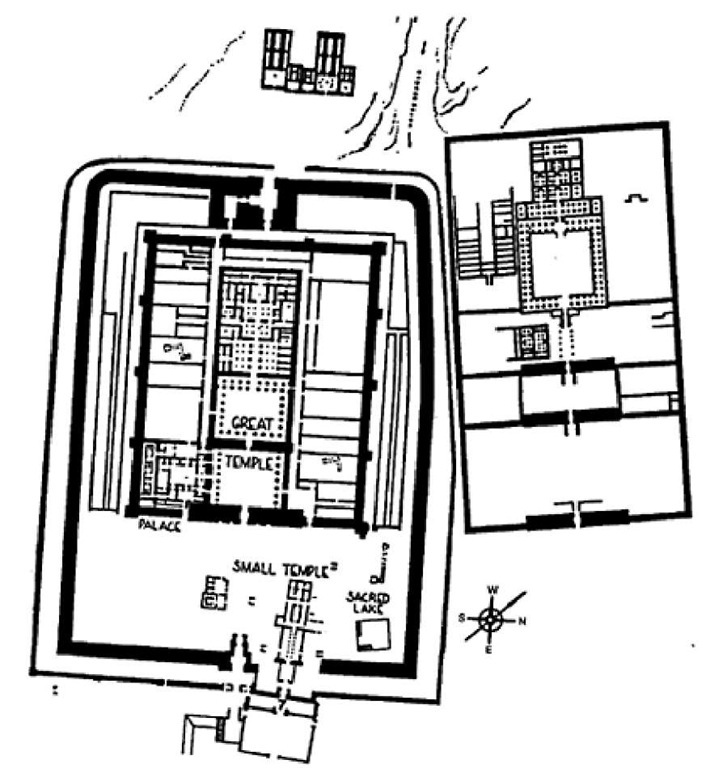

Figure 66 The monuments at Medinet Habu, overall plan.

The mortuary temple of Ramesses III, called "The Mansion of Millions of Years of King Ramesses III ‘United with Eternity’ in the Estate of Amen," was built adjoining Horemheb’s temple complex to the north. Its axis represents a compromise between the orientation of its neighbor and that of the small 18th Dynasty temple, which Ramesses III incorporated as a separate precinct inside his mortuary complex.

The ceremonial entrance to the complex was located on the east side, where archaeologists uncovered the remains of a harbor. Visitors entered the temple here, passing first between two "porters’ lodges" set into a low crenelated outer enclosure wall, and then through a high gate that pierces the more massive inner enclosure wall of mudbrick. The exterior of this tower is covered with reliefs, most of them depicting the king in triumph over Egypt’s enemies. A more intimate tone prevails inside the building, the chambers of which were reached through rooms and passages built into the mudbrick enclosure wall (now destroyed at these connecting points). Scenes on the stone walls of the gate’s inner rooms on the second and third stories depict Ramesses III in the company of his daughters and harim women. Another high gate, located on the western side of the complex, probably served as the everyday entrance for members of the temple staff who lived nearby. It was heavily damaged in a siege during the disturbances late in the 20th Dynasty and is a ruin today.

Nothing can be seen today of the walled enclosures and office buildings (all built out of mudbrick) that crowded the space between the eastern high gate and the main temple in Ramesses III’s time. The martial tone first seen on the exterior of the high gate is continued on the outer walls of the temple proper: in scenes of war and triumph over wild animals the king is seen as warding off his foes, and by extension, all enemies of Ma’at. Particularly notable are the wild game hunts depicted on the southwest face of the pylon. The triumph scenes inscribed on the pylon’s front are more conventional, but the battle scenes that run along the western and northern walls contain at least three sequences of historical importance (the Libyan wars of years 5 and 11, and the great war against the Sea Peoples, with its naval battle, in year 8). By contrast, most of the building’s south wall is inscribed with a liturgical calendar which details the offerings made at the various festivals celebrated in the temple each year. This placement is paralleled in temples of Ramesses II, both at the Ramesseum and at Abydos.

South of the main temple is the ceremonial palace that served both as a rest house for visiting royalty and a mock dwelling for the dead king’s spirit. In its original layout Ramesses III’s palace bore a close resemblance to its analog at the Ramesseum, but the plan was changed later in the king’s reign. It is this later plan that was partially restored by the Chicago expedition. It consists of two sets of public apartments (an audience hall next to a "living room" equipped with a small "window of appearances" for the king) and a corresponding pair of private apartments: one for the king, including a small throne room, bedroom and bath; and four smaller suites, linked by a corridor, along the back of the building. Marks on the south wall of the temple indicate the outline of the missing second story.

Similarities to Ramesses II’s mortuary building are not random, but extend also to the layout of the temple proper. Inside, the temple can be divided into three main areas: the first court, the most public part of the building, dominated on the south by the fagade of the palace, with its "window of appearances" from which the king presided over public audiences; the second, or "festival" court, with relief sequences illustrating the annual feasts of the gods Min and Sokar; and the main temple beyond, where its resident gods "lived." The basic elements in the plan—courtyards leading to columned halls and thence to inner cult rooms—are typical enough, but it is the decorative program that is the best guide to the way in which the temple functioned in ancient times. Two aspects of the king are reflected throughout. On the south side, many elements are associated with the king’s mortality and his apotheosis in the underworld; these themes are evoked by the palace and the "window of appearance" (first court) and the festival of Sokar, a singularly "dead" divinity who resides in the underworld and may represent the potency latent in the earth (second court). The king’s innate divinity and his identity are contrastingly represented on the north side of the building, i.e. in the colossal royal statues attached to the piers which hold up the northern portico in the first court, and in the festival scenes (second court) of Min, a fertility god who regularly (re)creates himself and thus exemplifies, like the sun, the eternal cycle of nature.

While the back of the temple has lost its upper parts to later quarrying, the cult rooms at the sides are tolerably well preserved. As before, the king’s deified mortal nature dominates on the south side: here we find a ceremonial treasury, chapels of the divine ancestors, Ramesses II and the ancient warrior god Montu, and a suite of rooms dedicated to Osiris, whose identity the dead king regularly assumed. The north side, which accommodates a number of elements necessary to the proper functioning of the building, is less consistently arranged. Following a series of chapels for gods (Ptah, Sokar, Wepwawet) residing in the temple, there is a "slaughterhouse," although it is unequipped for actual use, and must have served merely as a holding area for food offerings prepared elsewhere. The king’s innately divine identity is evoked once more, however, in the chapel dedicated to Ramesses III in his identity of the Amen resident in the temple. Further inside, this theme is resumed in the suite of Re-Horakhty, which like the tombs in the Valley of the Kings celebrates the king’s grasp of eternity as he joins the solar circuit; and in the chapel of the ennead, the gods who represent the divine pantheon in which the king takes his place. The two halves, human and divine, of both the king and his temple are bound together at the focal point of the building: this suite is dedicated to Amen-Re, King of the Gods, whose identity subsumed not only that of the pharaoh himself, but all other divine forces that prevailed in the Egyptians’ universe. Here, directly behind Amen’s bark sanctuary at the center of the building, was the principal false door, through which the dead king manifested himself in his temple. Other false doors were provided in the Osiris suite and the throne room of the first palace. Finally, a series of small rooms (entered through low, hidden doorways at the base of the back wall of Amen’s suite) probably represent the crypts in which the temple’s more esoteric equipment was stored.

Behind Ramesses III’s temple complex is a row of mudbrick funerary chapels, their interiors originally sheathed with stone blocks carved with scenes of their owners’ mortuary cults. While they were initially planned for favored contemporaries (including the mayor of Thebes), traces of later burials were found here as well. Toward the end of the 20th Dynasty, when the inhabitants of the workmen’s village at Deir el-Medina moved inside the complex for protection, urban sprawl began to engulf the temple: it is to the earliest phase of this occupation that belongs the house (or mortuary chapel) of the necropolis scribe Butehamen, constructed near the temple’s southwest corner. Much later are the four chapels of the Divine Votaresses of Amen, which were built over a period of about 200 years, from the last part of the 23rd Dynasty down to the end of the 26th Dynasty and the beginning of the first Persian domination. Only two of these chapels are substantially extant today: they belong to Amenirdis I, daughter of the Nubian king Kashta and to her niece and successor, Shepenwepet II. The latter was eventually converted to include the burials of Psamtik I’s daughter Nitocris and her mother, and thus boasts three mortuary chapels in a space originally designed for one. Two other chapels have disappeared: the latest, assigned to Ankhnesneferibre, daughter of Psamtik II, can be inferred only from the traces it left on the west wall of Shepenwepet II’s chapel; but the earliest building in the series, built for Amenirdis I’s predecessor, Shepenwepet I, still has its substructure, although nearly everything above ground has disappeared.

The process of urban transformation that began to overtake the site in the later 20th Dynasty continued unabated into the Christian era. Although the cult of Ramesses III lapsed at the end of the New Kingdom, the ongoing cult of Amen at the small temple continued to be a religious focus at the site and maintained its importance in late antiquity. Although the town’s inhabitants moved into the small temple when the community became Christian, patterns of occupation continued to favor the preservation of major buildings at Medinet Habu: for example, the "holy church of Djeme," built inside the second court of Ramesses III’s temple, reused the space in a fashion that spared it further destruction. The sudden abandonment of the town in the ninth century AD remains unexplained; although the site must have been mined in the centuries that followed—for example, blocks from the great temple made their way to the relatively modern Coptic monastery built on the low desert to the southwest—enough remained in situ to have made Medinet Habu uniquely revealing as a cross-section of human occupation over twenty-three centuries in West Thebes.

Medjay

Known by the name "Medjay" from the end of the Old Kingdom through the New Kingdom, the peoples of the Nubian Desert, Red Sea Hills and plain to the west (called the "Atbai") served the ancient Egyptians as caravaneers, police and professional soldiers. They were also formidable opponents and historical records frequently refer to clashes with them. Although some of their identifications have been contested, the Medjay probably belonged to the great cultural substratum that appears under various names in all periods of recorded history: as "Meded" in the Kushite records of the first millennium BC, "Belhem" (?) in Egyptian demotic texts, "Blemmyes" in Greek and Roman texts, and "Bedja" in Arabic. Perhaps some were also designated more generically as "Iwntiu" (pillar-folk) by the Egyptians, and "Troglodytes" (cave-dwellers) by the Greeks. The Medjay were an ancient manifestation of one of Africa’s great surviving cultural continua which today occupy the desert and coast from Wadi Hammamat in Egypt to Somalia.

Climatic changes in the last four millennia have altered living conditions in the Red Sea Hills and Atbai, but they have always contrasted sharply with the Western Desert. The eroded plateau and mountains cause rain to fall during the monsoon season, and the modest accumulation of water provides pasturage for herds of domestic animals, which in ancient times included sheep, goats and cattle. The limited and seasonal resources stimulated movement at all times, with the inhabitants retreating in the dry months toward the mountains, where they have sometimes escaped the burning heat in caves, or toward the Nile Valley. During the rainy season in late summer, they expanded outward, especially in the Sudanese Butana, an area between the Atbara River, the main Nile and the Blue Nile. This south-north seasonal movement created possibilities for trade and immigration that sustained contact between Egypt and the fringes of Ethiopia (Punt or part of Punt) and ensured that the peoples of the region were never really isolated.

The region of the Red Sea Hills was important even in early times, when its products were imported to Egypt and Lower Nubia in considerable amounts. Because the region had relatively well-traveled trade routes, it has been proposed as the staging area for both Mesopotamian influence and significant early interchange with Sudan. The clearest evidence for peoples from this region in early times is a group of stelae from 2nd Dynasty tombs at Helwan, which show Puntites or (related) people from the Atbai and a small number of related contemporary tombs in Nubia.

Little is known about peoples from the northern Red Sea Hills and adjacent Atbai during the Old Kingdom except for sporadic references to campaigns against them, and possibly similar peoples north of the Wadi Hammamat designated to secure desert routes to the mines and quarries, and port facilities of the Red Sea trade with Punt. The first real mention of the Medjay appears in the 6th Dynasty records at Aswan, both royal inscriptions and tomb biographies of the nomarchs and caravan conductors of Elephantine. There the Medjay are mentioned with the peoples of Nubia, who were consolidating a newly intensified control of the region under the wary eye and sometimes interfering hand of the Egyptians. Although Nubians played a significant role in the turbulence of the First Intermediate Period, little is known about the Medjay in the early Middle Kingdom; they may be first depicted as tall, emaciated cattle herdsmen in the tomb chapels in Middle Egypt dating to the 12th Dynasty.

The Medjay likewise played a more significant role in the records of campaigns against Nubia and Kush that dominated Egypt’s attention in those areas and culminated in the erection of huge fortifications in Lower Nubia and near Egypt’s southern boundary in the Middle Kingdom. The only records available from the forts indicate that Medjay formed a substantial part of the garrison force, and they were used to prevent infiltration by other Medjay. They even patrolled the desert at the fort of Elephantine, and the fort at Serra East in Lower Nubia was named Khesef-Medjay, i.e. "repelling the Medjay." At the same time, texts name two major Medjay principalities (Auwshek and Webat-Sepet) among the entities in Nubia as formidable enough to be cursed.

Medjay were active in the disturbances of the Second Intermediate Period, when they have been associated with the archaeological evidence known as the "Pan-grave" culture. In the New Kingdom, after the wars that left Egypt in control of the Nile Valley as far south as the Fourth Cataract, the Medjay are hardly mentioned as a force, but some were employed as a kind of police force. The name became a title for "policeman" and was held by Egyptians in the later New Kingdom.

The term "Medjay" is not known after the New Kingdom and there is very little archaeological evidence for Nubia and Sudan from the end of the New Kingdom to about 900/800 BC. Cemeteries near the Second Cataract dating to that period or shortly after have tombs much like the earlier Pan-graves, and Nubian pottery from them includes types found in the earliest Kushite tumulus graves at el-Kurru, dating to the tenth or ninth century BC. Later Kushite rulers of the fifth and fourth centuries BC fought determined campaigns against a people called the "Meded," who were probably the ancient Medjay, and the "Rehres," who may have been a subgroup operating near Meroe.

The history of the Medjay did not end with these brief mentions, for their location and role were later occupied by peoples known to the Greeks as "Blemmyes," and to the Arabs as "Beja." While the earlier accounts mix mythical or fantastical elements, the resulting descriptions can be reconciled with the often impoverished life near the Red Sea. At times, the Blemmye-Beja groups formed powerful coalitions, controlling trade, operating emerald mines and battling with major powers. In the third through fifth centuries AD they thrust into Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia, raiding as far west as Kharga Oasis and as far north as Sinai.

Although expelled once from Upper Egypt by Roman forces commanded by General Probus, they returned, even setting up a kingdom modeled in part on the late Roman/Byzantine court. They left distinctive archaeological remains in the northern part of Lower Nubia and along the desert edges in southern Upper Egypt. In the end they were only controlled by difficult campaigning and a rivalry with another Nubian group, the Noubadians.

Meir

The modern village of Meir is situated due west of the town el-Qusiya in Middle Egypt. To the southwest of the village is the archaeological site (27°27′ N, 30°43′ E), the necropolis of the former capital of Nome XIV of Upper Egypt.

Very little is known about this site, which was extensively pillaged in the nineteenth century and carelessly excavated in the twentieth century. There is not even an accurate site plan, but some of the the Old and Middle Kingdom tombs are nicely recorded in publications. Decorated with exquisite reliefs, these rock-cut tombs were carved in the low hills west of Meir. A First Intermediate Period cemetery possibly existed on the desert plain to the east.

Although finds at the site range in date from the Old Kingdom to Graeco-Roman times, the archaeological record is very poor for most periods except the Old and Middle Kingdom. From these periods are five concentrations of rock-cut tombs, designated A, B, C, D and E, in an order from north to south. The most important Old Kingdom group is A, where the finely decorated and well preserved tombs of the chief priests of the cult of Hathor of Qusiya are located. Tomb A2, of Pepi-ankh, is well known for its unusually detailed representation of the funerary ritual. Groups B and C contain tombs of the 12th Dynasty, with lively and extremely well carved reliefs and paintings, including the famous ancestor list of the governor (nomarch) Ukhhotep III (Tomb B4). Tomb C1, belonging to Ukhhotep IV, is unusual in that, apart from the tomb owner, only females are depicted on its walls. Subsidiary tombs here have also produced a high quantity of Middle Kingdom coffins inscribed with funerary texts known as the Coffin Texts.