Lahun, pyramid complex of Senusret II

The pyramid complex of Senusret II, which was built at the entrance to the Fayum about 70km south of Dahshur (29°14′ N, 30°58′ E), has not been investigated in recent times and the only information is from Flinders Petrie’s excavations conducted in 1889-90, 1914 and 1920-1. Although the whole complex, which consists of a valley temple, causeway(?), mortuary temple, pyramid and northern chapel, generally follows the early 12th Dynasty plan of his predecessors’ pyramids, there are major innovations which reflect the strong influence of the cult of Osiris.

Similar in construction to the pyramids of Senusret I or Amenemhat II, the core of this pyramid consists of a system of gridded walls of mudbrick and stone built above a 12m high rock nucleus. The spaces between the walls were filled with mudbricks and the whole core was covered by a thick casing of Tura limestone. The entrance to the burial chambers, however, was transferred from the north side to the south, probably as a protective measure from tomb robbers. Here a vertical shaft was found underaeath the floor slab of the tomb of a princess (No. 10), which leads to a horizontal passage running north. From a small chamber at the northern end a short corridor opens toward the west and leads into the burial chamber, which is not aligned beneath the center of the pyramid but to the southeast. The burial apartment which is surrounded by a corridor may reflect the idea of a tomb of Osiris. The row of trees planted along the outer enclosure wall, where pits were found on the east, south and west sides, probably also has its origin in Osirian traditions.

The remains of a valley temple were found at the edge of the pyramid town of Kahun, about 1km east of the pyramid. From here a causeway once led to the pyramid complex. A few remains of the mortuary temple are in the eastern court, which seems to have been considerably reduced in size from those of the earlier 12th Dynasty pyramids. No plan of this building is available, but columns found in the Ramesside temple of Ihnasya, inscribed with the name of Senusret II, seem to have come from this site and probably formed part of an open court.

A small subsidiary pyramid (circa 26m square) in the northeastern corner of the pyramid’s outer court, as well as eight mastaba superstructures farther west, remain enigmatic since there is no evidence of shafts or burial chambers in any of them. Fragments of wall paintings, an altar and a statue found in the debris of the subsidiary pyramid seem to indicate the existence of a northern chapel.

Lahun, town

The Middle Kingdom town now known as el-Lahun (29°13′ N, 30°59′ E) was built circa 1895 BC to house the workmen engaged in building the nearby pyramid and temples of King Senusret II. In addition to the workforce and their families, the town accommodated the officials and overseers who supervised the work, the priests and other personnel employed in the king’s pyramid temple where his mortuary cult was performed after his burial, and an associated community of doctors, scribes, craftsmen and tradesmen. The site was discovered and excavated by Flinders Petrie, who began work there in 1889. Petrie asked an old man in the nearby village what the ancient town was called and was told "Medinet Kahun." Today the town is sometimes referred to as "Kahun" to differentiate it from the site of Senusret II’s pyramid at el-Lahun. In antiquity both the town and the adjoining pyramid temple were known as "Hetep-Senusret" (Senusret is satisfied).

Lahun lies in the Fayum region southwest of Cairo. This area owes its remarkable fertility to local springs of water and the Bahr Yusef, a channel through which the waters of the Nile flow into the lake known today as Birket el-Qarun (Lake Moeris in antiquity). The area has always provided excellent hunting and fishing, and in antiquity, kings and courtiers visited it regularly to enjoy these pastimes. The kings of the 12 th Dynasty chose to build there and to be buried in pyramids on the edge of the desert, which brought unprecedented activity and prosperity to the area.

In 1888-9, Petrie began his excavations of several sites in the area at the northern and southern ends of the great dike of the Fayum mouth. These included the Lahun pyramid and its surrounding cemetery; two temples, the smaller one adjoining the pyramid on the east and the other lying circa 800m away on the edge of the desert; the town of Lahun, to the north of the larger temple; and, at the southern end of the dike, the New Kingdom town of Gurob or Medinet Gurob.

The discovery and excavation of Lahun town were important for several reasons. It was the first time that an archaeologist had uncovered a complete plan of an Egyptian town. Specially built to house the workforce, it had been laid out by one architect on a regular plan. Petrie claimed that there had been two periods of occupation, the first for about 100 years from the 12th to 13th Dynasties, and then a brief reoccupation of part of the site in the 18th Dynasty. However, this interpretation of the evidence is now disputed: there may have been a continuous but dwindling occupation from the earlier to the later periods.

Second, the site appears to have been deserted in some haste, and Petrie discovered that many of the houses were still standing and contained property left behind by their owners. These artifacts provide a unique insight into the contemporary living conditions. Artifacts from Lahun include domestic wares, workmen’s tools, agricultural and weaving equipment, toys and games, jewelry and toilet equipment. Some artifacts have been preserved here which would have been considered too mundane to be included among tomb goods.

Third, in addition to these artifacts of everyday use, the collection of papyri discovered in the town provides a written record of civil and domestic life, and includes details of legal, medical and veterinary practices. Of particular importance are the lists and records which throw light on the working conditions of the pyramid builders, and the Kahun Medical Papyrus, which is the earliest known document on gynecology in the world. It includes details of tests to ascertain sterility, pregnancy and the sex of unborn children, as well as gynaecological prescriptions and contraceptive measures. Finally, because of the wealth of tools and equipment found among the artifacts at Lahun, there is an unparalleled opportunity to study the technological developments of the period, such as important advances in metal-working techniques.

Petrie excavated approximately two-thirds of the site over a two-year period. The town was surrounded by a massive mudbrick wall, and was divided internally by a wall into two areas, east and west, which were both of the same Middle Kingdom date. In the larger, eastern section there was an "acropolis" which probably had temporary quarters where the king stayed when he was inspecting progress on the construction of his pyramid. There were also five large houses which accommodated the officials who were in charge of the royal works. In the western area of this section were rows of workmen’s houses. All the streets had channels down the middle to take away waste water and occasional rain. Altogether, Petrie cleared over 2,000 chambers, and in his records of these excavations he describes his working methods in some detail.

The houses, also built of mudbrick, were usually arranged so that several rooms were grouped together with one outer door opening onto the street. They were one storey in elevation, with stairs leading to the roof. Some were vaulted with a barrel roof of mudbrick, but more often they were made with beams of wood on which poles were placed. Bundles of straw or reeds were lashed to the poles and mud plaster was then applied to the inside and outside surfaces.

The walls of the rooms were also smoothly plastered with mud (Petrie found two plasterers’ floats at the site). Walls were sometimes painted in red, yellow and white, and the best room was often decorated with a dado. In the larger rooms, columns were used to support the roof, and most doorways had wooden thresholds. There was evidence that rats had tunneled through holes in virtually all the houses.

The artifacts from Lahun were ultimately distributed among various museums, but the largest proportion of this material was divided more or less equally between what is now in the Petrie Museum at University College London, and the Manchester University Museum. Artifacts from Lahun include domestic items such as ceramic dishes, scoops, brushes and a grinder, and wooden furniture (including stools and boxes). A fire-stick, which worked on the bow-drill principle, was the first such tool found in Egypt. The unique collection of tools found here included building tools (a mudbrick mold and plasterers’ floats), stone-working tools and carpenters’ tools. Petrie discovered a metal caster’s shop with some of its original contents, and it was a noticeable feature of the site that stone and flint tools continued to be used along with metal tools. There were also agricultural implements (the town produced its own food), fishing equipment and a set of tools for textile production. Unlike tomb equipment, which was often intended for religious or ceremonial purposes, the artifacts from Lahun were for domestic use or were used in craft production and trade.

In the houses there were also craft goods belonging to women, including jewelry and cosmetic equipment. Toys and games have also survived: there were game boards, balls, tops, tipcats and small mud toys, presumably made by children. However, Petrie also found evidence of a more sophisticated toy-making industry. Wooden dolls and quantities of hair prepared for insertion into holes in their heads were found in one house, which probably belonged to a doll-maker. Some of the artifacts from Lahun have no parallels elsewhere, since they were regarded as humble, everyday objects which were never placed in tombs.

There is also evidence relating to the religious practices of the inhabitants. These include some unusual stone stands in the form of human figures, which were probably used for making offerings in the houses, and a set of equipment—including magic wands and a well-preserved face mask representing the household god Bes—which may have been owned by a local magician.

In recent times, the artifacts from Lahun have been intensively re-examined, including neutron activation analysis of pottery and metals, and studies of the textile tools and botanical specimens. The theory originally proposed by Petrie, that some of the town’s inhabitants were not of Egyptian origin, has also been reconsidered. Petrie excavated sherds at the site which he described as "foreign," and more specifically as "Greek." This identification was originally treated with skepticism by classical scholars, but with the subsequent discovery of Minoan civilization it was possible to determine that some of the Lahun sherds, which had patterns incorporating swirls and spirals, were indeed examples of the Kamares Ware found on Crete. However, not all these "Minoan" sherds at Lahun were true imports; some were identified stylistically as local Egyptian imitations. It is uncertain if even the true imports were brought to Lahun by immigrants or arrived there through trade connections.

At Lahun Petrie also discovered weights and measures, some of which were of non-Egyptian origin, and he believed that these had been introduced by foreign traders and merchants. Some of the religious practices found there may not be Egyptian; the stone offering stands placed in the houses are unusual in style and the burial of infants in boxes found near the houses was not an Egyptian custom. A copper torque found in a house at Lahun may also indicate foreign associations. Very few examples of these neck ornaments have been found in Egypt, although they were worn for over five centuries in southwest Asia and were produced at Byblos on the Syrian coast.

Perhaps the papyri discovered at Lahun provide the strongest evidence for the presence of foreigners in the town. In the legal documents, they are mentioned as servants in households, and some are also identified in the lists of temple personnel, as participants in a festival in the temple of Senusret II. The word aamu (loosely translated as "Asiatic") was placed after the individual’s name to indicate his foreign origin. Some aamu are mentioned in the military or police units, and they must have existed at Lahun in sufficient numbers to warrant positions of "officer in charge of Asiatic troops" and "scribe of Asiatics."

Petrie’s hypothesis was that foreigners were first brought to Egypt as captives to work on public projects, following Egypt’s military engagements with other peoples in the 11th Dynasty. Some of Lahun’s inhabitants may have been their descendants, but others probably came as traders or itinerant craftsmen; they may have originated from several homelands, including Syria, Palestine, the Aegean islands and Cyprus.

There are also different theories regarding the end of the Middle Kingdom occupation at Lahun. This may have been caused by declining local economic conditions or by foreign infiltration and harassment. Some evidence suggests that the evacuation of the site was sudden and unplanned: the inhabitants left behind a quantity and range of personal possessions, which may have been the result of a natural disaster or even an epidemic. The evacuation, however, may have been gradual and partial so that by the New Kingdom only a token number of houses in the western quarter remained occupied. The suggestion that the workforce departed to another place once their construction of the pyramid was completed is untenable since they would surely have taken their tools with them, and the length of the Middle Kingdom occupation at Lahun (circa 100 years) would have exceeded the period required for construction of a pyramid.

New studies of the artifacts and current excavations at the site by Nicholas Millet of the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, will undoubtedly continue to reveal more information about the daily existence of this community and its wider historical significance.

Late period private tombs

Private tombs of the Late period are known in more than forty cemeteries in Egypt. At many of these sites, however, there is only evidence of scattered funerary artifacts, stelae and fragments of inscribed blocks. In some cases the dating is uncertain and the remains could also date to the Graeco-Roman period. In most cemeteries, Late period tombs have no distinctive character and follow local traditions (rock-cut tombs, mastabas or small shaft-tombs, sometimes with superstructures, and vaulted mudbrick structures in the Delta). Some cemeteries consist only of simple pit-graves. It was also customary to usurp and adapt older tombs, where many burials of the Late period were frequently stacked into the existing chambers.

At Abydos several cemeteries of the Late period are known, mainly with tombs of modest size. These tombs consist of a mastaba (superstructure) with a shaft leading to undecorated rock-cut chambers which sometimes contain multiple burials. At one cemetery there are small, steep mudbrick pyramids, with the burial in a subterranean chamber. At el-Amra, near Abydos, shaft-tombs with mudbrick superstructures in the shape of a small temple or shrine were traditional from the 18th Dynasty until the end of the Late period.

At Heliopolis, besides some simple shaft-tombs, tombs were discovered with burial chambers constructed of limestone blocks in pits. These tombs are similar to the large shaft-tombs at Saqqara (see below), but are much smaller in size. They often contained multiple burials of families.

In Baharia Oasis, several rock-cut tombs were made for a family of governors and priests during the Saite period (26th Dynasty). The subterranean chambers, with religious scenes painted on plastered walls, are reached by a shaft and consist of a pillared central hall flanked by smaller side rooms. Superstructures are not preserved, but probably existed. A similar tomb of the same period, consisting of two sunken courts with small side chambers, is located in Siwa Oasis. These Oases’ tombs seem to be patterned after a type of tomb found in the Theban necropolis during the Late period.

It was indeed in the cemeteries of the two capitals, Thebes and Memphis, where new concepts for the tomb developed during the Late period. In western Thebes the tradition of the "classical" Theban rock-cut tomb came to an end after the collapse of the New Kingdom. No individual private tombs seem to exist for the 21st Dynasty, and many coffins were stacked into caches, mostly in older tombs. The elaborate decoration of the coffins, with an extensive iconographic repertory, took over some of the religious functions of the earlier decorated tomb chambers.

During the 22nd-23rd Dynasties a new type of tomb appeared in western Thebes, although it had a long tradition in other places, such as el-Amra. This tomb consisted of a mudbrick superstructure shaped like a small temple, where the funerary cult took place, with one or more shafts leading to the burial chambers cut in the bedrock. Placed on the plain and not on the slopes of the desert hills, this "new" tomb type was the prelude to future developments.

During the Kushite and Saite periods (25th and 26th Dynasties) a Late period necropolis par excellence developed in western Thebes in the valley named el-Asasif. Passing through this valley are the causeways to the mortuary temples of Queen Hatshepsut, Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II and Tuthmose III (at Deir el-Bahri). In the Late period, the causeways of the two kings’ temples were no longer in use and the area was used by high officials of the 25th and 26th Dynasties who established their "funerary palaces" in prominent positions near Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahri.

The two most elaborate structures here were built by Montuemhat, Governor of Upper Egypt, and Pedamenopet, Chief Lector Priest. Other monumental tombs were those of the High Stewards of the God’s Wives or the Divine Votaresses (priestesses of Amen), who were princesses holding royal power in the Theban region. The landscape of el-Asasif is dominated by the remains of these huge mudbrick superstructures, while some of the rock-cut substructures surpass in size and complexity other Theban private tombs or the royal tombs in the nearby Valley of the Kings.

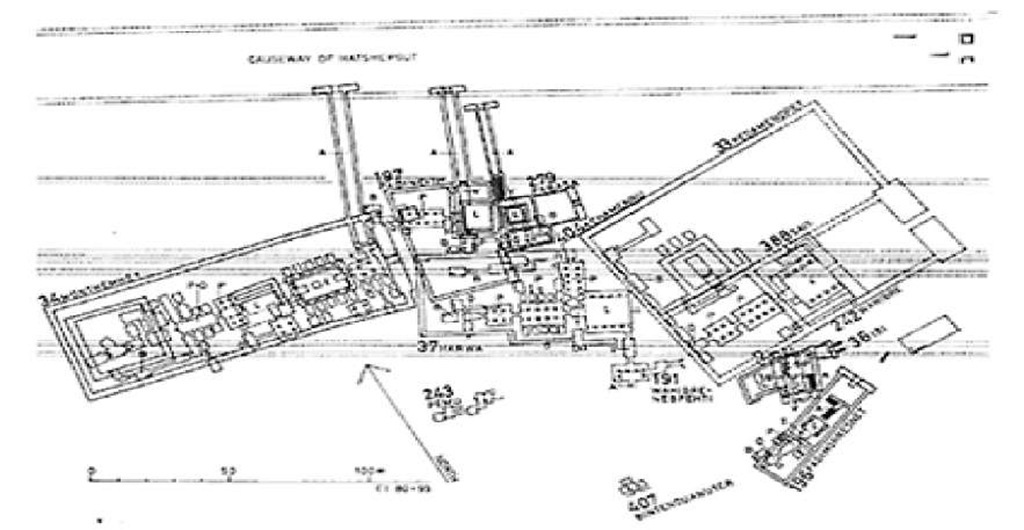

The architectural plan of the el-Asasif tombs has five basic elements: (1) the superstructure, Thick lines indicate superstructures. A=descending stairway; V=vestibule; L=sunken court; T=portal niche; P=pillared hall; O=offering hall; B=burial appartments.

Figure 54 Theban necropolis, western part of the Late period necropolis at el-Asasif

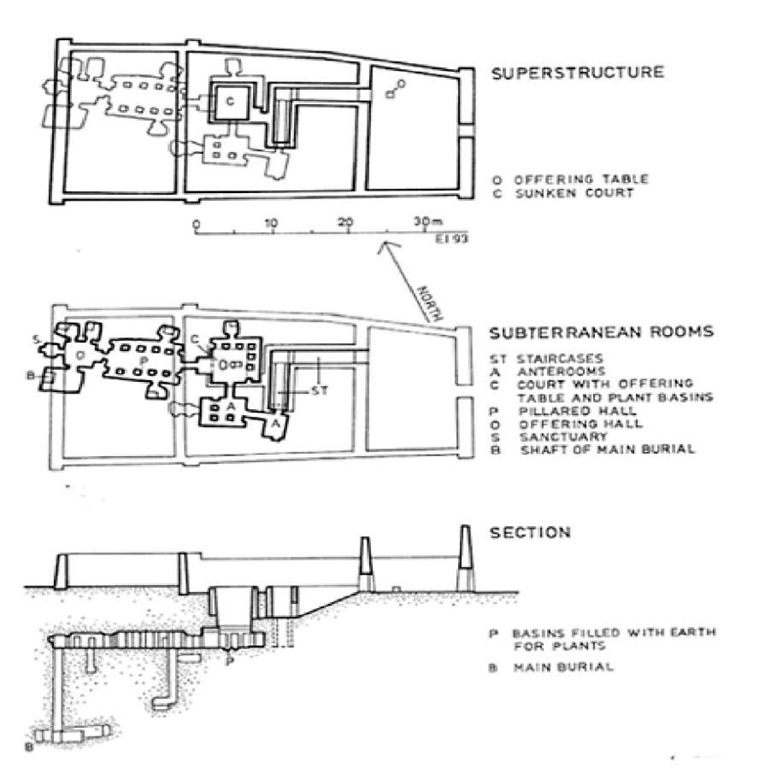

(2) descending staircase with antechamber and vestibule, (3) sunken court, (4) rock-cut sub-terranean rooms, and (5) burial chambers. As in domestic architecture, a tripartite division forms the design principle for the whole structure (superstructure, rock-cut halls, burial apartments), with increasing secludedness in each section. This general plan, with variations and modifications, is found in all larger tombs, although local traditions from all periods and archaizing tendencies are of considerable influence in details.

The mudbrick superstructures of these tombs, modeled after the royal mortuary temples, usually contain three vast open courts. The inaccessible third court covers the area of the underground halls and chambers. Sometimes a small mudbrick pyramid of the type known from Abydos marks the position of the burial chamber. The entrance pylon is oriented toward the east, or, in the western part of el-Asasif, toward the point where the procession of a ceremony called the "Beautiful Feast of the Valley" first came into sight. On the outside of some superstructures is the archaizing motif of recessed mudbrick paneling, a simplified version of the "palace fagade" design, known from the "funerary palaces" of the Early Dynastic period.

In some tombs the descending stairway is entered through a small pylon located along the southern edge of Hatshepsut’s causeway. One of the motives for this arrangement was the desire to participate in the "Beautiful Feast of the Valley" as its procession passed by here on the way to Deir el-Bahri. At the foot of the stairway, one or more antechambers or vestibules give access via a bent axis to the sunken court.

The sunken court, on the level of the substructure but open to the sky, is one of the most prominent and innovative features. Here the daily funerary cult was performed at an offering table, located in front of the niche of the entrance to the underground rooms. Plants were grown in a basin filled with earth, which symbolized the tomb of Osiris, with vegetation growing out of the dead god’s body.

The subterranean complex, entered only for the performance of special rituals, consists of one or two pillared halls with side chambers, an offering chamber and a sanctuary where Osiris was believed to reside. The arrangement of these rooms, of varying complexity in each tomb, is derived from both domestic and temple architecture. The side chambers of the pillared hall often contain shafts for the burials of relatives of the tomb owner, so that the complex is also a family tomb.

The royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings, with their succession of halls and sloping passages, are the model for the burial chambers of the el-Asasif tombs. From the last hall a shaft descends to the sarcophagus chamber. Sometimes the shaft starts directly from the level of the cult complex.

Figure 55 A typical tomb of the 26th Dynasty at el-Asasif (belonging to Ankh-Hor, High Steward of the Divine Votaress) Executed in fine relief, decorations in the superstructure, descending staircase and sunken court pertain to contact of the dead with the outside world. In the subterranean halls the descent into the underworld is the main theme; in the burial chambers the entire realm of the Egyptian netherworld is represented, as in the royal tombs.

The large tombs at el-Asasif were plundered soon after completion and many secondary burials were deposited here until the Ptolemaic period. Between and around these tombs a maze of smaller structures of the "chapel-and-shaft" type created a veritable "City of the Dead."

In the cemeteries of Memphis local traditions continued (rock-cut tombs, shaft-tombs and tomb chapels), sometimes with very individual solutions. For example, the tomb chapel of Thery at Giza is built of limestone blocks arranged in a cross-shaped plan, with vaulted chambers. The vizier Bakenrenef was the only official to prefer an underground complex of the monumental Theban type, which was carved in the cliff at Saqqara. At Giza, at Abusir and especially at Saqqara, innovative developments are marked by the desire to provide the greatest security for the burial. These tombs belonged to high officials of the 26th Dynasty, but for unknown reasons are called "Persian" tombs. Most of these burials remained untouched until their archaeological investigation in modern times. They were probably inspired by the great pit-tombs in the funerary complex of King Zoser, which were explored in the 26th Dynasty.

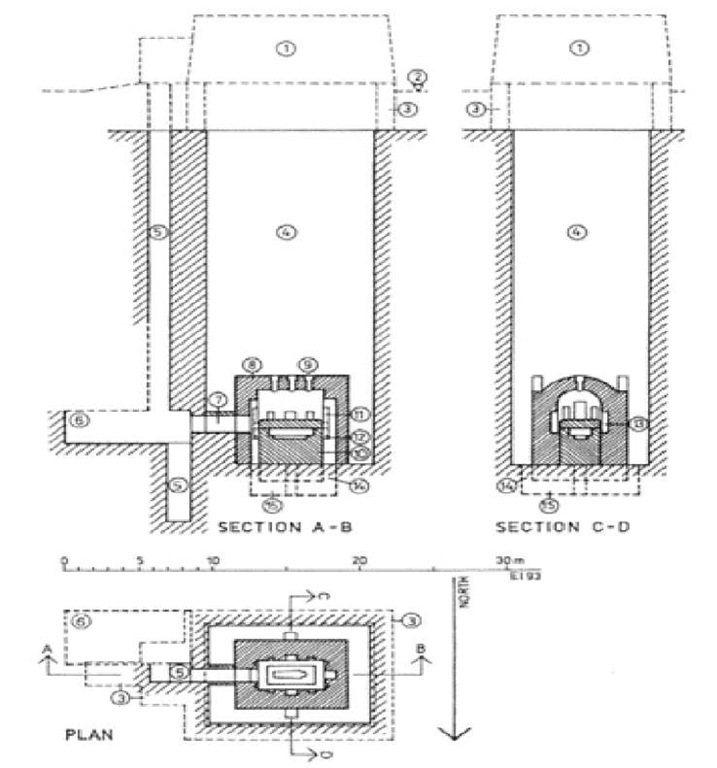

The main feature of these 26th Dynasty tombs is a huge rectangular shaft or pit, about 11x8m, cut about 30m deep in the bedrock. A subsidiary shaft, about 1.4m by 1.4m, is always several meters deeper than the main shaft. A burial chamber built of limestone blocks is located at the bottom of the main shaft. In fact, this "burial chamber," with its vaulted roof and square corner posts, is the outermost of a series of nesting sarcophagi. It has the shape of a sarcophagus known since the 1st Dynasty, imitating an early house form. the chamber fits closely around a huge limestone sarcophagus. Inside the limestone sarcophagus is an anthropoid sarcophagus of slate or basalt, in which is the anthropoid wooden coffin.

After construction the chamber was connected to the subsidiary shaft by a small passage made of limestone slabs or vaulted mudbricks, then the large pit was filled with sand. The actual burial was conducted via the small shaft and corridor, and there is evidence of an ingenious series of devices to insure its security. The basalt sarcophagus was closed and then the lid of the large sarcophagus was lowered. The lid has square projections at the small sides, which fit into grooves in the walls of the chamber, so that the lid could be supported by wooden props resting on sand. The sand was released to a lower level through small apertures, allowing the lid to descend slowly into place. Then the pottery jars, which had plugged holes in the roof vault of the chamber, were broken and sand streamed in from the fill of the large shaft. In addition, the brick vault of the passage could be broken before the small shaft was filled. Any robbers who wanted to come near the sarcophagus, even via the small shaft, would have had to remove the entire sand fill of about 2000 cubic meters. It has been suggested that the sarcophagus, weighing up to 100 tons, was lowered in place by the sand which was filled into the large shaft. If such an operation actually took place, the downward extension of the subsidiary shaft may have played some part in the gradual removal of the sand.

1 superstructure (reconstructed outline)

2 approximate ancient surface level

3 foundations of superstructure

4 main shaft filled with sand

5 subsidiary shaft

6 chamber for storage of building equipment and handling of burial (?)

7 connecting passage between subsidiary shaft and burial chamber

8 vaulted burial chamber built of limestone blocks

9 round openings in vault of burial chamber, temporarily closed with pottery jars

10 monolithic limestone sarcophagus

11 groove holding wooden prop for support of sarcophagus lid

12 opening to release sand under prop

13 niche for canopic jars and shawabti boxes

14 small shaft for conveying sand

15 sand-filled chamber under sarcophagus

Figure 56 A typical tomb of the 26th Dynasty at Saqqara (belonging to Amen-Tefnakht, Commander of the Recruits of the Royal Guards)

The interior walls of the burial chamber, and sometimes their outer faces, are decorated with inscriptions in sunken relief, mainly of mortuary texts related to the Pyramid Texts. Canopic jars (for the preserved viscera) and shawabti (servant figure) boxes were deposited in niches next to the sarcophagus. The superstructures of these tombs are now completely destroyed, except for some remains of foundations following the outline of the pit, with an extension on the eastern side, presumably where a chapel for the mortuary cult was located. The architecture of these superstructures must have been elaborate, as fragments of limestone blocks, and palmiform and composite capitals demonstrate.

More steps to increase security were made in tombs at Abusir and Giza, where the main shaft is surrounded by an even deeper sand-filled trench. Both are connected by large openings through which the sand could flow freely in either direction, and no part could be emptied separately.

With its careful imitation of a contemporary temple building, the tomb chapel of Petosiris at Tuna el-Gebel, erected at the end of the Dynastic period, represents the final development of the Late period private tomb of the chapel-and-shaft type. In western Thebes, the Late period "funerary palaces" are an attempt to insure eternal life for their owners by mobilizing all traditional funerary concepts in religion and architecture, including those of royal tombs. The results are, despite a general archaizing tendency, original and distinctive monuments. The achievement of ultimate security in the Saqqara tombs, together with the return to an archaic tomb form, can be seen as the final point of development in Egyptian tomb architecture.