Elephantine

During most of pharaonic times Egypt’s southern border was located at the town of Elephantine. It occupied an island in the Nile (24°05′ N, 32°53′ E), at the northern entrance to the First Cataract opposite modern Aswan, of which it was the ancient forerunner.

All that remains of the ancient town (then called Abu) is a mound circa 350m wide and up to 15m high. The first excavations were undertaken at the beginning of this century, mainly to search for papyri rather than to investigate the remains of the town. The current program of comprehensive exploration of the entire town site, begun in 1969, continues to uncover increasingly detailed evidence of 4,000 years of the town’s history, unparalleled to date at any other ancient Egyptian settlement.

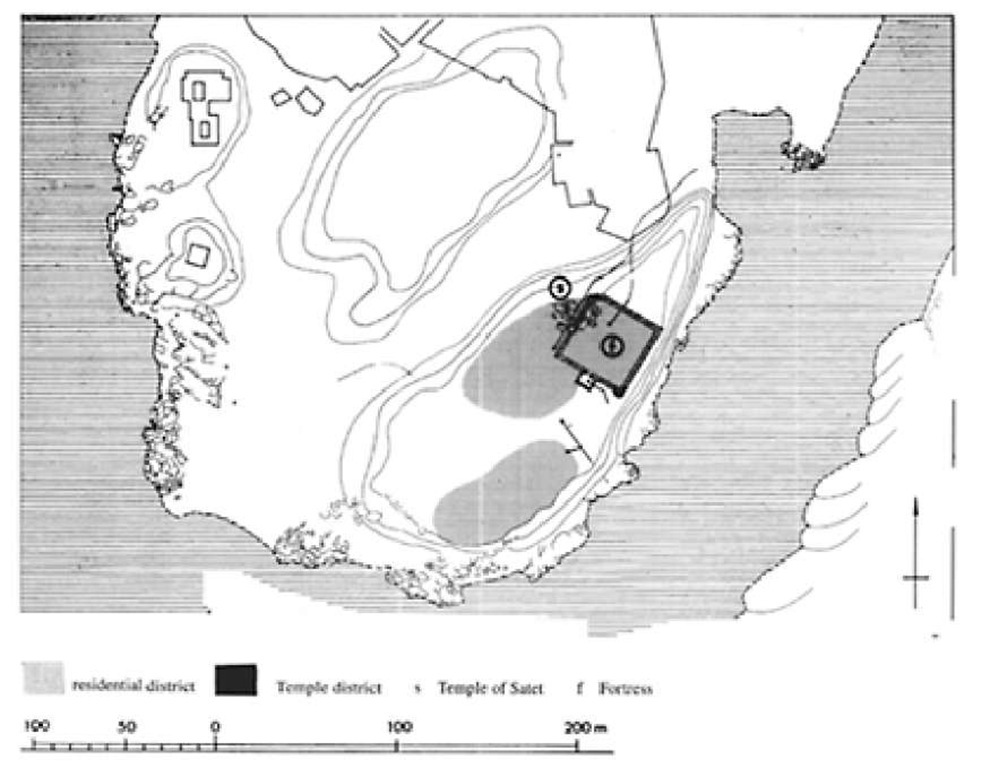

The earliest traces of the settlement identified so far date to the middle of the fourth millennium BC. They were found on the eastern of two granite ridges that then comprised the habitable area of the island. This ‘east isle’ preserves the remains of the sanctuary of the "Lady of the Town," the antelope goddess Satet. Dating to around 3200 BC, the earliest sanctuary was a modest mudbrick construction between three tall granite boulders.

It is unclear whether the inhabitants of the early settlement at Elephantine were Egyptianized Nubians whose culture had expanded northwards of the First Cataract, or if the site was already an Egyptian outpost. The ethnic identity of the earliest inhabitants is probably irrelevant to the significance of the settlement, which, because of its location at the northern end of the unnavigable cataract area, functioned as a center for trade with the south. The chief landing place then may have been located at the sheltered bay directly north of the east isle. The pharaonic name of the town, which means "ivory", as well as "elephant," might well hint at what was traded by the southerners with the Predynastic Egyptians.

With the unification of the Egyptian state circa 3100-3000 BC, the town’s function as a trading center became linked with state control. In the course of the 1st Dynasty, a fortress was built on the highest point of the east isle’s shore, and it seems that it housed a non-local, i.e. Egyptian, occupying force. A little later the whole settlement was surrounded by a mudbrick wall, which enclosed the entire south part of the east isle. This implies that from the first an area was reserved for an increase in population resulting from the dissolution of smaller settlements in the region and/or further immigration from the north. In the 2nd Dynasty the remaining part of the east isle was included within the fortification walls, which were maintained for the next 600-700 years, throughout the Old Kingdom. At the same time the walls of the 1st Dynasty fortress gradually disappeared beneath the increasingly densely populated settlement, and the whole town began to take on the appearance of a fortification. In hieroglyphic texts from the Old Kingdom and down into the Middle Kingdom, the sign for "fortress" was included in the writing of Abu.

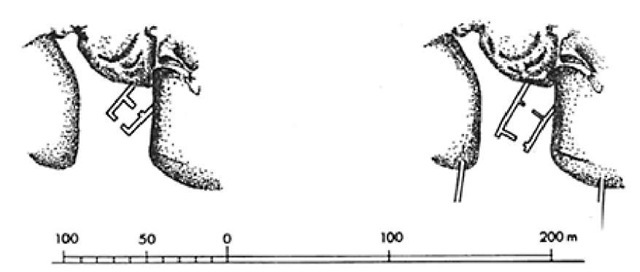

Figure 30 Temple of Satet, Elephantine: 1st/2nd Dynasties

In the town, administrative buildings, residences and various industrial areas are distinguished by architectural remains and artifacts. Toward the end of the 3rd Dynasty a large complex was built on the west isle. Its most notable feature was a small step pyramid, similar to others at some contemporary important sites in Middle and Upper Egypt, such as Nagada and Abydos (Sinki). Like the 1st Dynasty fortress, the complex was a project of the central authority. The pyramid seems to have represented the fictive presence of the king, and was a symbolic means of reinforcing state control implicit in Elephantine’s role in the collection and distribution of goods. Possibly a statue cult was associated with the pyramid. The entire complex was short-lived. It fell into neglect and the area began to be developed for other purposes. In the late 4th Dynasty craft workshops were located there, and in the 5th Dynasty the town cemetery expanded into the area.

Figure 31 Plan of Elephantine in the 1st Dynasty

Throughout the Old Kingdom the temple of the goddess of the town, Satet, was repeatedly rebuilt on its original site. It remained essentially a modest mudbrick structure with a forecourt. A granite sanctuary for the goddess’s statue survives from a rebuilding ordered by Pepi I in the early 6th Dynasty. Numerous votive offerings, both royal and private, have been recovered from these early levels. Rock inscriptions document visits by later 6th Dynasty kings. By this time at the latest, the ram-headed god Khnum of the cataract region possessed a cult place within Satet’s temple.

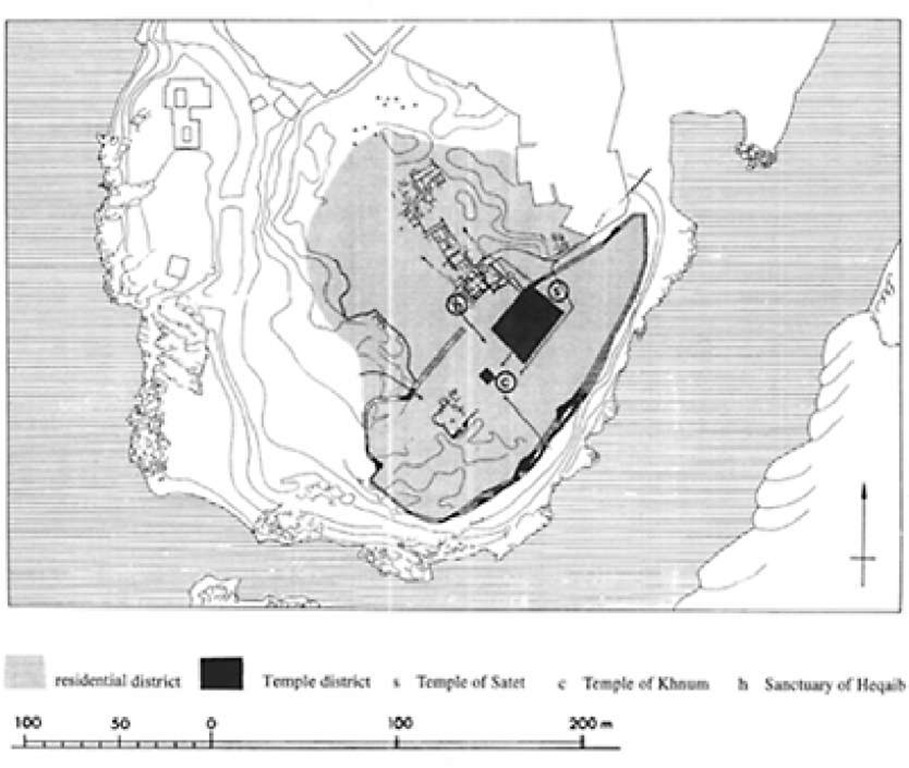

The collapse of the central authority in the First Intermediate Period further increased the significance of Elephantine within Upper Egypt. Kings of the 11th Dynasty, who resided in Thebes, rebuilt the Satet temple several times and for the first time stone was used for some elements. Around 2000 BC the first ruler of the reunified kingdom of Upper and Lower Egypt, Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II, built an entirely new sanctuary and added an installation for the celebration of the Nile flood, which, according to ancient Egyptian belief, began at Elephantine.

Already in the late Old Kingdom the settlement was expanding beyond the earlier fortifications. With the strengthening of the unified Egyptian state under Mentuhotep II and the 12th Dynasty, town growth at Elephantine gained momentum. Senusret I advanced from there to the Second Cataract and subjected the whole of Lower Nubia to Egyptian rule. For the first time, Elephantine lost its function as a border town and instead became an important administrative and economic center for trade to the south, beyond the First Cataract. Presumably, the enlarged town continued to be surrounded by a wall, but the archaeological evidence does not yet demonstrate this.

When the new Satet temple was only 100 years old, Senusret I replaced it with a richly decorated stone structure connected to a courtyard, built for the inhabitants of the town to celebrate the Nile Festival. Also at this time, Khnum acquired a temple of his own in the elevated town center.

During the 11th Dynasty a third cult center had sprung up to the northwest of the Satet temple, for the worship of Heqaib. He was a mayor (nomarch) of the town, who had apparently manifested such exemplary leadership in the difficult times of the late Old Kingdom that after his death he became revered as the local saint. His original, modest cult chapel was first rebuilt in the 11th Dynasty and then again at the beginning of the 12th Dynasty. For the next few centuries the governors of the town followed suit and set up their own memorial chapels there, in addition to their rock-cut tombs at the site of Qubbet el-Hawa. Numerous other officials dedicated stelae and statues in the Heqaib sanctuary.

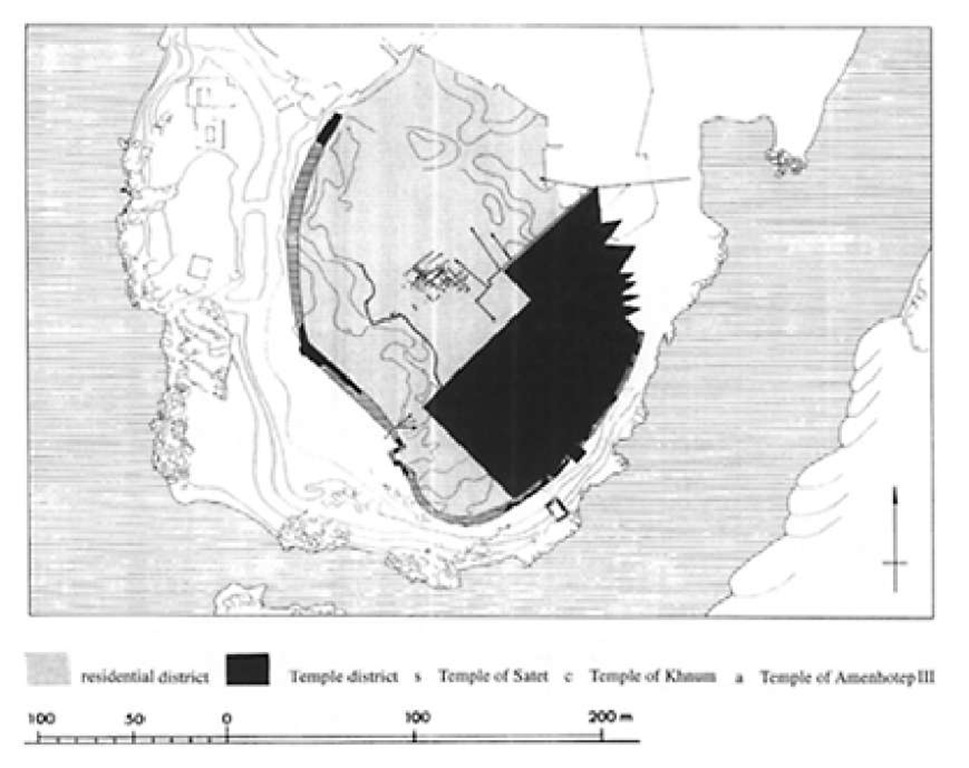

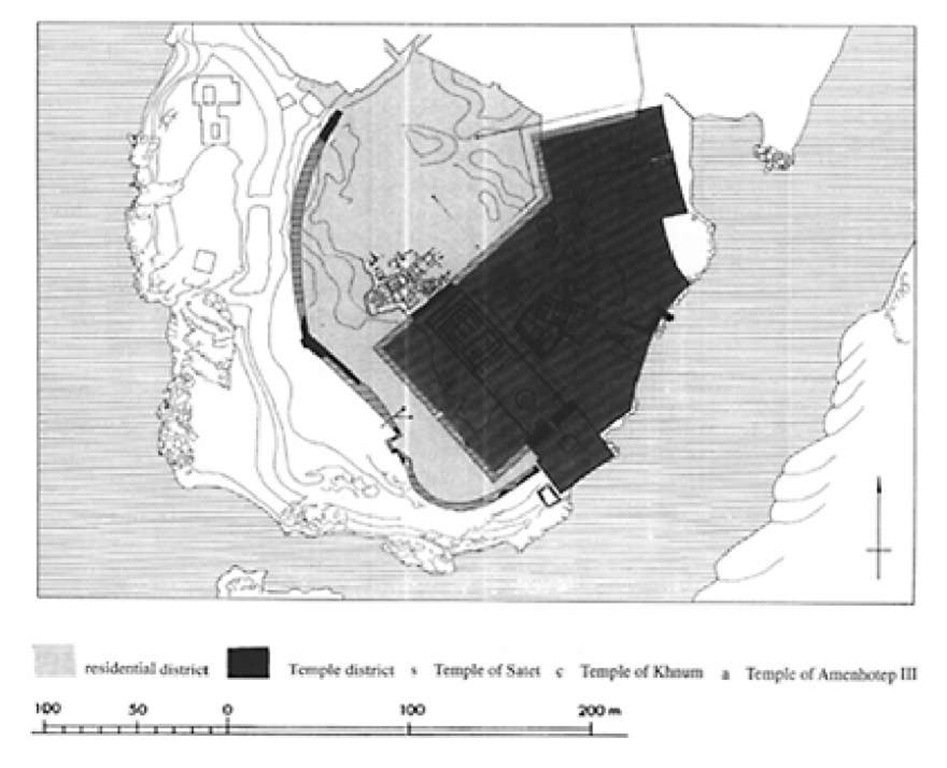

For a time during the Second Intermediate Period, after the second collapse of the central government, Egypt’s southern border was again at Elephantine, until the kings of the early 18th Dynasty reconquered Nubia and extended the border as far south as the Fourth Cataract. Elephantine flourished once again and Queen Hatshepsut and Tuthmose III built large new temples to both Satet and Khnum. In the interim, the cult of Khnum, who was worshipped throughout Egypt, had eclipsed Satet at Elephantine. In the 18th Dynasty, but primarily in the 19th and 20th Dynasties, his temple was further enlarged. Along the processional way from the harbor to the temples of the town, Amenhotep III erected a way-station, apparently in connection with the rebuilding of the installations for the Nile Festival.

The temples and associated economic institutions grew to occupy nearly one-third of the area of the town. It is thus probably no coincidence that Syene, the ancient name for Aswan on the mainland, first appears in texts of this period. Scattered houses and industrial areas may have expanded farther into the farmland to the north of the town. An indication that this development occurred is the way-station built by Ramesses II outside the town to the northwest.

With the beginning of the Third Intermediate Period, when there were repeated internal conflicts in Egypt and Nubia became independent, the strategic aspect of this town once again came to the fore. Stelae are the only monuments to attest the kings of this period and of the Kushite 25th Dynasty at Elephantine. With the 26th Dynasty construction was resumed on the town’s temples. A nilometer was added to Khnum’s temple to measure the height of the flood waters. Shortly before the dynasty ended with the Persian conquest of Egypt, Amasis added a colonnade to the Satet temple.

Figure 32 Plan of Elephantine in the Middle Kingdom

During the Persian occupation of Egypt Elephantine served as a bulwark against threats not only from the south. The occupying force utilized by the Persians in Elephantine consisted at least in part of members of the preexisting Aramean and Jewish colony. Its members already possessed a temple to Yahweh before the Persians’ arrival. Apparently the enlargement of Khnum’s temple in the 30th Dynasty resulted in its loss with scarcely a trace. The ruins of a number of non-Egyptian-type houses survived from which important papyri relating to early Judaism could be salvaged.

Under the kings of the 30th Dynasty, another era of prosperity began for Elephantine which continued under the Ptolemies and then, beginning in 30 BC, under the Romans. Nectanebo I (30th Dynasty) added to the New Kingdom temple to Khnum. His second successor, Nectanebo II, began a large new building but only managed to complete the sanctuary and a small forecourt. The Ptolemies, especially Ptolemy VI and VIII, resumed construction on this temple, which was finally completed under the Roman emperor Augustus when a large river terrace was built. Considerably smaller, but also well appointed with a river terrace and nilometer, was the new temple complex of Satet (begun by Ptolemy VI), part of which had to be relinquished to serve as a cemetery for the sacred rams of the Khnum temple.

In the Roman period the river bank between the two temple terraces was built up and also the area to the north of Satet’s nilometer. A monumental staircase with a sanctuary to the Nile was constructed at the town harbor. The exact locations of two other temples within the sacred precinct are still unclear. Altogether the temples and their dependencies ultimately covered almost half the area of the town. In the residential areas there are well-preserved remains of houses from the Ptolemaic and early Roman periods. These are two storey structures crowded together. Because of the loss of the sites uppermost levels, only the cellars have survived from a few houses of the later Roman period.

Because the temple town came to occupy over nearly half the ancient site in Graeco-Roman times, the daily life of trade and administration apparently shifted to Aswan on the east bank of the river. With the triumph of Christianity in the early fourth century AD Aswan overtook Elephantine for good. Elephantine forfeited its role as a fortress. In the fifth century a company (cohort) of soldiers, stationed on the island to strengthen border defenses against attacks by marauding tribes from the Eastern Desert, built a fortified camp in the great court of the Khnum temple.

Figure 33 Plan of Elephantine in the New Kingdom

Figure 34 Plan of Elephantine in the Graeco-Roman period

It is likely that the work of dismantling the temples for building material had begun by this time and in the following centuries, it led to the loss of virtually all but the foundations of the main temples and the total disappearance of smaller structures. Arabic sources from the early Middle Ages describe a monastery and two churches on Elephantine. The plan of a small early sixth-century church in the courtyard of the temple of Khnum could be recovered. The scattered remains of an important, slightly later basilica, found scattered in the town’s residential area suggests it once stood there. With the increasing influence of Islam in Egypt from the seventh century, the last Christian phase of the town’s history was comparatively short-lived. It probably ended not much later than the thirteenth or fourteenth century.